The University of Chicago Vile Affections: Medieval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxes, Inkwells, Speech and Formulas DRAFT

Boxes, Inkwells, Speech and Formulas DRAFT Richard J. Fateman March 10, 2006 1 Introduction This paper sets out some designs for entering mathematical formulas into a computer system. An initial approach to this task suggests that the previous model, namely writing mathematics on paper or chalkboard, should lead to a natural computer system using a stylus for writing on a tablet. For feedback and for presentation such as in this paper, we use the typesetting capabilities of Knuth’s TEX system to show how “properly typeset” expressions might appear. We use TEX here to show our design for an interactive input scheme, under implementation. For this to work, an interactive system must make expressions appear approximately in the same sequences as illustrated, on a computer display. The solid color boxes that appear in the incomplete forms are intended as invitations for the user to continue writing out a formula, continuing from within one of those boxes. Think of them as “virtual inkwells.” For example, an attempt to write a superscript must begin by dipping the stylus (or mouse) in the superscript inkwell. An attempt to write an operand adjacent to an existing must begin in that inkwell. Initiating writing elsewhere on the screen will have no proper ink and will not contribute to the formula entry. We also point out that speaking the terms, rather than writing them, may provide more accurate communication. At this point we suggest you look ahead a page or two to see some pictures of inkwells. 1.1 Why Inkwells? This ink-well-based constrained input provides an obvious basis for cooperation between the human entering a formula and the supporting computer program. -

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

National News Local News

LOCAL NEWS NATIONAL NEWS -Justin Vedder #1 Pick in Alternate Dimension Bizarro NFL Draft -Felonious Monk Bops Brother -“Man” Pronounced “Dead” by Illiterate Paramedic -“Duck Hunt” Remains Least Popular Nesticle Download -Skateboarding Now a Crime -Phone.com Calls Ghostbusters.com -White Student Only Vaguely Understands His Chinese Tattoo -Battered Women’s Support Site Gets 5 Million Hits -”Stanfurd” Fan Chased from Cheese ‘N’ Stuff for Knife-Chasing, Spitting -Government Requires Monitoring of Nocturnal Emissions May 2000 Vol. 9 Issue 5 Local Idiots Mad Scientist Emerges Stumble Upon from Laboratory with Printing Press New Wheel Design BY BRET HEILIG BY LUKE FILOSE According to Dusseldorf, GUY WITH FACE wheel design technology has ad- FUCKING LOONY TOON vanced considerably in the past Students tittered briefly last Doctor Klaus “White Knuck- five millennia, but strong vested month as The California Patriot, les” Dusseldorf shocked the interests in the international making its official publishing de- world Monday when he emerged wheel lobby have stifled innova- but, delivered a walloping dose of from his lab deep in the Swiss Alps tion. “I’ve received death healthy conservative thought to with a potentially groundbreaking threats,” he said. “Apparently, the UC campus. Featuring several discovery: he claims to have re- someone is making a lot of money correctly spelled words and dis- invented the wheel. on the current wheel and doesn’t playing a keen sense of how to Looking haggard but confi- appreciate my efforts.” Asked to operate Microsoft Paint, the soon- dent outside of his laboratory, in describe his new wheel design, to-be-famous first issue left a last- front of a large gathering of the Dusseldorf was less forthcoming. -

Semen Arousal: Its Prevalence, Relationship to HIV Risk Practices

C S & lini ID ca A l f R o e l s Klein, J AIDS Clin Res 2016, 7:2 a e Journal of n a r r DOI: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000546 c u h o J ISSN: 2155-6113 AIDS & Clinical Research Research Article Open Access Semen Arousal: Its Prevalence, Relationship to HIV Risk Practices, and Predictors among Men Using the Internet to Find Male Partners for Unprotected Sex Hugh Klein* Kensington Research Institute, USA Abstract Purpose: This paper examines the extent to which men who use the Internet to find other men for unprotected sex are aroused by semen. It also looks at the relationship between semen arousal and involvement in HIV risk practices, and the factors associated with higher levels of semen arousal. Methods: 332 men who used any of 16 websites targeting unprotected sex completed 90-minute telephone interviews. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. A random sampling strategy was used. Semen arousal was assessed by four questions asking men how much they were turned on by the way that semen smelled, tasted, looked, and felt. Results: 65.1% of the men found at least one sensory aspect of semen to be “fairly” or “very” arousing, compared to 10.2% being “not very” or “not at all” aroused by all four sensory aspects of semen. Multivariate analysis revealed that semen arousal was related to greater involvement in HIV risk practices, even when the impact of other salient factors such as demographic characteristics, HIV serostatus, and psychological functioning was taken into account. Five factors were found to underlie greater levels of semen arousal: not being African American, self-identification as a sexual “bottom,” being better educated, being HIV-positive, and being more depressed. -

Kate Bornstein: a Transgender Transsexual Postm Odern Tiresias

Kate Bornstein: A Transgender Transsexual Postm odern Tiresias From Shannon Bell Gender School "Sex is fucking, everything else is gender" Kate told us on the first day of gender school: a four part, sixteen hour Cross-Gendered Perform ance Workshop which was part of Buddies in Bad Tim es Theatre sum m er school program . Kate is a Buddhist M-to-F transsexual perform ance artist and gender educator. Kate has been both m ale and fem ale and now is not one nor the other, but both-and-neither, as indicated in the title of her play The Opposite Sex...is Neither! The Cross-Gender W orkshop aim ed at deconstructing gender: shedding gender, trying on a new gender; getting to zero point and then construct ing a new gender. The first section of the workshop dealt with gender theory and learning how to build gender cues: physical cues - body, posture, hair, clothing, voice, skin, m ovem ent, space, weight; behavioral cues - m anners, decorum , protocol, deportm ent; textual cues - stories, histories, associates, relationships; power dynam ics - top, bottom , entitlem ent/ not; and sexual orientation (to whom am I attracted). This w as preparation for constructing a character which we would work on perform ing for the following three sessions. At the final class we did a one hour Zen walk across the theatre stage. For the first half-hour of the walk we shed all our acquired gender characteristics; for t he second half we took on our character's gender traits. The only constraint on selecting a character was that it be som e version of the opposite gender. -

Sexual Adventurism Cover 2

Sexual AdventurismAdventurism among Sydney gay men Gary Smith Heather Worth Susan Kippax Sexual adventurismadventurism among Sydney gay men Gary Smith Heather Worth Susan Kippax Monograph 3/2004 National Centre in HIV Social Research Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Copies of this monograph or any other publication from this project may be obtained by contacting: National Centre in HIV Social Research Level 2, Webster Building The University of New South Wales Sydney NSW 2052 AUSTRALIA Telephone: (61 2) 9385 6776 Fax: (61 2) 9385 6455 [email protected] nchsr.arts.unsw.edu.au © National Centre in HIV Social Research 2004 ISBN 1 875978 78 X The National Centre in HIV Social Research is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing and is affiliated with the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of New South Wales. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii report summary 1 KEY FINDINGS 1 Part 1 Sexual adventurism and subculture 1 Part 2 Sexual practice and risk 1 Part 3 Drug use 2 RECOMMENDATIONS 3 introduction 5 background and method 7 BACKGROUND 7 Defining ‘culture’ and ‘subculture’ 8 METHOD 9 Recruitment and data analysis 9 The sample 9 thematic analysis 11 PART 1 SEXUAL ADVENTURE AND SUBCULTURE 11 Adventurism as non-normative sex 11 Individual and group change over time 13 Adventurous spaces for sex 15 Transgression 15 A subculture of sexual adventurism 16 PART 2 SEXUAL ADVENTURISM AND SAFE SEX 19 Casual sex, adventurism and risk 20 HIV-negative men and unsafe sex 20 HIV-positive men and unsafe sex 22 Disclosure of HIV status: a double bind 25 PART 3 DRUG USE AND ADVENTUROUS SEX 26 Managing drug use 27 Sexual safety and drug use 29 REFERENCES 31 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is the product of the efforts many people. -

Handout #7: Clinical Definition of Child Sexual Abuse

Clinical Definition of Child Sexual Abuse The sexual acts that will be described in this section are abusive clinically when the factors discussed in the previous section are present as the examples illustrate. The sexual acts will be listed in order of severity and intrusiveness, the least severe and intrusive being discussed first. Non-contact Acts Offender making sexual comments to the child - Example: A coach told a team member he had a fine body, and they should find a time to explore one another's bodies. He told the boy he has done this with other team members, and they had enjoyed it. Offender exposing intimate parts to the child, sometimes accompanied by masturbation. - Example: A grandfather required that his 6-year-old granddaughter kneel in front of him and watch while he masturbated naked. Voyeurism (peeping). - Example: A stepfather made a hole in the bathroom wall. He watched his stepdaughter when she was toileting (and instructed her to watch him). Offender showing child pornographic materials, such as pictures, books, or movies. - Example: Mother and father had their 6- and 8-year-old daughters accompany them to viewings of adult pornographic movies at a neighbor's house. Offender induces child to undress and/or masturbate self. - Example: Neighbor paid a 13-year-old emotionally disturbed girl $5 to undress and parade naked in front of him. The Pennsylvania Child Welfare Training Program 522: Supervisory Issues in Child Sexual Abuse Handout #7, Page 1 of 4 Clinical Definition of Child Sexual Abuse (cont’d) Sexual Contact Offender touching the child's intimate parts (genitals, buttocks, breasts). -

ACROSS LANDS FORLORN: the EPIC JOURNEY of the HERO, from HOMER to CHANDLER Volume One Sergio Sergi

ACROSS LANDS FORLORN: THE EPIC JOURNEY OF THE HERO, FROM HOMER TO CHANDLER Volume One Sergio Sergi ACROSS LANDS FORLORN: THE EPIC JOURNEY OF THE HERO, FROM HOMER TO CHANDLER. SERGIO SERGI B.A. University of Adelaide M.A. University of Ottawa M.A University of Sydney A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Canberra. March 2006 i Certificate of authorship of thesis. Except where clearly acknowledged in footnotes, quotations and the bibliography, I certify that I am the sole author of the thesis submitted today entitled ‘Across lands forlorn: The epic journey of the hero from Homer to Chandler.’ I further certify that to the best of my knowledge the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. The material in this thesis has not been the basis of an award of any other degree or diploma except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. This thesis complies with University requirements for a thesis as set out in http://www.canberra.edu.au/secretariat/goldbook/forms/thesisrqmt. pdf …………………………. Signature of Candidate …………………………. Signature of Chair of the supervisory panel Date: ……………………………. Acknowledgements I acknowledge a number of people who have helped with the realization of this thesis which was begun at the University of New England. Professor Peter Toohey, before he left that University, listened to my ideas about the hero and encouraged me to develop them into this thesis. I am most grateful to him for the confidence he placed in my abilities to conduct a complex study. -

Tinder-Ing Desire: the Circuit of Culture, Gamified Dating and Creating Desirable Selves

Tinder-ing Desire: The Circuit of Culture, Gamified Dating and Creating Desirable Selves Tanya F. Oishi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: LeiLani Nishime, Chair Ralina Joseph Carmen Gonzalez Program Authorized to Offer Degree Communication 2 ©Copyright 2019 Tanya F. Oishi 3 University of Washington Abstract Tinder-ing Desire: Tanya F. Oishi Chair of the Supervisory Committee: LeiLani Nishime Communication This dissertation starts at intersection of race, gender, and technology, all of which will be discussed in depth throughout this project, and the fluid state of being constituted and being undone by one another. It is in this state of vulnerability that relationships are initiated, through technology that these relationships are shaped and facilitated, and within the constraints of social expectations that these interactions are able/allowed to occur (Duck, 2011). As life becomes more mediated and interactions more facilitated through technological means, focusing on relationships facilitated through dating apps is illustrative of the ways in which mobile technologies are changing the way we communicate with one another. The introduction provides the theoretical overview of the literature off of which the rest of the dissertation builds its arguments: the importance of interpersonal connections, the positionality of Asian men in the U.S., and the mutual shaping of society and technology, as well 4 as a justification for a mixed methodological approach to these areas of inquiry. The second chapter looks at the subreddit r/Tinder Profile Review Week thread to see how individuals seek feedback on creating a desirable self and describes how these impression management strategies of Asian men differ from the group which is comprised predominantly by white men. -

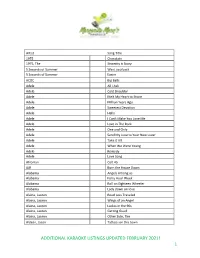

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 IX – BOEOTIA – A COLONY OF THE MINI AND THE FLEGI .....71 X – COLONIZATION