Horses, Copyright 2002 Julia Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coat Color in Horses

COAT COLOR IN HORSES Tabulation of Color of 42,165 Horses Allows Definite Conclusions to Be Drawn as to Value of Different Factors—Errors in Registry and in Genetic Description of Colors—Connection Between Gray and Roan.1 W. S. ANDERSON Assistant in Horse Husbandry, Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, Lexington, Ky. URST, Wilson, Harper, Sturte- brown, black and chestnut. As a rule vant, Anderson and others the variations of each of these colors have published papers on the are not recorded in the stud books. Inheritance of Coat Colors in The gray coat is made up of white Horses. It is the purpose of the writer and black hairs and varies from the to give a summary of all the available almost white to the almost black, and figures on the subject and his interpre- includes a large class of horses whose tation of them. The sources of the coat is of the dappled pattern. When figures collected are the various Stud young, the gray horse exhibits this Books. As a matter of fact these can dappled condition or is what is desig- not be accurate. I, myself, have used nated iron gray, but as age comes on the American Saddle Horse Register. the dapples disappear and white and This Register has been compiled within black hairs are to be found. Later on two or three decades and has been the black may almost be lost and result revised within a decade. I find errors in a white horse. This white, however, in it approximating two percent, for does not seem to be of the same nature color and as great a percent, of errors as the white found on spotted ponies that might be considered of a typo- and some classes of horses. -

I . the Color Gene C

THE ABC OF COLOR INHERITANCE IN HORSES W. E. CASTLE Division of Genetics, University of California, Berkeley, California Received October, 27, 1947 HE study of color inheritance in horses was begun in the early days of Tgenetics. Indeed many facts concerning it had already been established earlier, by DARWINin his book on “Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.” At irregular inteivals since then, new attempts have been made to collect and classify in terms of genetic factors the records contained in stud books concerning the colors of colts in relation to the colors of their sires and dams. A full bibliography is given by CREWand BuCHANAN-SMITH (19301. By such studies, we have acquired very full information as to what color a colt may be expected to have, when the color of its parents and grandparents is known. This knowledge is empirical rather than experimental in nature. For horses being slow breeding and expensive are rarely available for direct experi- mental study, such as can be made with the small laboratory mammals, mice, rats, rabbits and guinea pigs. We have definite information that color inheritance in horses involves the existence of mutant genes similar to those demonstrated by experimental studies to be involved in color inheritance of other mammals. But the horse genes have been given special names, as they were successively discovered, and it is difficult at present to correlate them with the better known names and geneic symbols used by the experimental breeders. The present paper is an attempt to make such a correlation. Just as in morphological studies comparative anatomy was found useful and still is used to establish homologies between systems of organs, so in mammalian genetics, a comparative study of gene action in the production of coat colors and color patterns may also be of value. -

Die Vererbung Der Fellfarbe Bei Pferden

Die Vererbung der Fellfarbe bei Pferden Von Noémie Pauwels Fach: Biologie Lehrerin: Frau Laubenbacher Abgabetermin: 08.03.2011 Gliederung: 1 Einleitung 1.1 Erläuterung 1.2 Genetische Grundlagen 2 Basisfarben und ihre Merkmale 2.1 Basisfarben 2.2 Rappe 2.3 Brauner 2.4 Fuchs 2.5 Multiple Allelie 3 Aufhellungen 3.1 Cream 3.1.1 Einfachaufhellungen 3.1.2 Doppelaufhellung 3.2 Champagne 3.3 Falben 3.4 Windfarben 3.5 Sonstige Aufhellungen 4 Fehlende Pigmentierung 4.1 Schecken 4.2 Tiger 4.3 Roan 4.4 Weißgeborene 5 Fortschreitende Depigmentierung 5.1 Schimmel 6 Spezielle Farbausprägungen 6.1 Kopf- und Beinabzeichen 6.3 Farbsprenkel und Äpfelung 6.4 Flächenpigmentierung 6.5 Diffuse Farbausprägungen 6.6 Augen und Hufhorn 7 Zusatzmaterial 7.1 Fußnoten 7.2 Bildmaterial 7.3 Arbeitstagebuch 7.4 Quellen 7.5 Selbstständigkeitserklärung 1 Einleitung 1.1Erläuterung Das Thema „Die Vererbung der Fellfarbe bei Pferden“ habe ich gewählt, da wir auf der Rainbow-Valley Ranch in diesem Jahr mit unserer Zucht begonnen haben und nun die ersten Fohlen geboren werden. Meiner Meinung nach sollte jeder Züchter über bestimmte Grundkenntnisse der Farbvererbung verfügen, da einige Farbschläge auch gesundheitliche Risiken für das Pferd bergen. Eine besondere oder seltene Farbe ist sicher ansprechend und erhöht den Wert eines Pferdes, dennoch sollte stets die Gesundheit und die Qualität des Pferdes im Vordergrund stehen. Zunächst werde ich einige genetische Grundlagen erläutern, damit die verschiedenen Erbgänge der Farb-Gene verständlich sind. Erst danach werden die drei möglichen Basisfarben und dann deren Aufhellungen und Muster, sowie die fortschreitende Depigmentierung aufgeführt. 1.2 Genetische Grundlagen Die Erbanlage für die Fellfarbe liegt beim Pferd in den Chromosomen, die, wie beim Menschen, immer paarweise vorliegen. -

19/07/2018 Page 1 of 9 Genetic Screening Tests Available Symbol

Genetic Screening Tests available Symbol Name Description of variant effects Genetic Disease Testing CA is a neurological disorder that affects the cells in the cerebellum, causing head tremors, ataxia and other effects. Affected horses are more likely to fall and are generally not safe to ride. Symptoms appear from 6 weeks to around 4 months old. CA has been linked to a mutation in the TOE1 Cerebellar CA gene and is a recessive disorder, meaning that a horse must Abiotrophy be homozygous (CA/CA) to be affected. If a horse is a carrier (CA/n), it will not show any clinical signs of CA, but it will pass the variant on to approximately half its offspring. Mating to other carriers should be avoided to prevent the birth of an affected foal. LFS causes neurological dysfunction in foals. The symptoms include seizures, hyperextension of the limbs, neck and back, leg paddling, and inability to stand. As the name suggests, LFS also dilutes to the coat to a pale lavender pink or silver colour. The foal will not improve and will die, so it should be euthanised. LFS is a recessive disorder so two copies of the Lavender Foal defective version of the MYO5A gene must be inherited LFS Syndrome (LFS/LFS) for a foal to be affected. If a horse is a carrier (LFS/n), it will not show any clinical signs of LFS. However, there is a 50% chance it will pass the variant to its offspring, so mating to other carriers should be avoided to prevent the birth of an affected foal. -

Horse Sale Update

Jann Parker Billings Livestock Commission Horse Sales Horse Sale Manager HORSE SALE UPDATE August/September 2021 Summer's #1 Show Headlined by performance and speed bred horses, Billings Livestock’s “August Special Catalog Sale” August 27-28 welcomed 746 head of horses and kicked off Friday afternoon with a UBRC “Pistols and Crystals” tour stop barrel race and full performance preview. All horses were sold on premise at Billings Live- as the top two selling draft crosses brought stock with the ShowCase Sale Session entries $12,500 and $12,000. offered to online buyers as well. Megan Wells, Buffalo, WY earned the The top five horses averaged $19,600. fast time for a BLS Sale Horse at the UBRC Gentle ruled the day Barrel Race aboard her con- and gentle he was, Hip 185 “Ima signment Hip 106 “Doc Two Eyed Invader” a 2009 Billings' Triple” a 2011 AQHA Sorrel AQHA Bay Gelding x Kis Battle Gelding sired by Docs Para- Song x Ki Two Eyed offered Loose Market On dise and out of a Triple Chick by Paul Beckstead, Fairview, bred dam. UT achieved top sale position Full Tilt A consistant 1D/ with a $25,000 sale price. 486 Offered Loose 2D barrel horse, the 16 hand The Beckstead’s had gelding also ran poles, and owned him since he was a foal Top Loose $6,800 sold to Frank Welsh, Junction and the kind, willing, all-around 175 Head at $1,000 or City OH for $18,000. gelding was a finished head, better Affordability lives heel, breakaway horse as well at Billings, too, where 69 head as having been used on barrels, 114 Head at $1,500+ of catalog horses brought be- poles, trails, and on the ranch. -

Homozygous Tobiano and Homozygous Black Could Be Winners for Your Breeding Program, If You Know How to Play Your Cards

By IRENE STAMATELAKYS Homozygous tobiano and homozygous black could be winners for your breeding program, if you know how to play your cards. L L I T S K C O T S N N A Y S E T R U O C n poker, a pair is not much to brag gets one of the pair from the sire and the in equine color genetics. If your goal about. Two pairs are just a hair bet - other of the pair from the dam.” is a black foal, and you’ve drawn the ter. But in equine color genetics, a Every gene has an address—a spe - Agouti allele, you’re out of luck. pair—or, even better, two—could cific site on a specific chromosome. be one of the best hands you’ll ever We call this address a locus—plural The Agouti effect hold. We’re talking about a sure bet— being loci. Quite often, geneticists use Approximately 20 percent of horses a pair of tobiano or black genes. the locus name to refer to a gene. registered with the APHA are bay. If Any Paint breeder will tell you that When a gene comes in different you also include the colors derived producing a quality foal that will forms, those variations are called alle - from bay—buckskin, dun, bay roan bring in top dollar is a gamble. In this les. For example, there is a tobiano and perlino—almost one-quarter of business, there are no guarantees. But allele and a non-tobiano allele. Either registered Paints carry and express the what if you could reduce some of the one can occur at the tobiano locus, Agouti allele, symbolized by an upper - risk in your breeding program as well but each chromosome can only carry case A. -

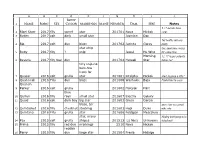

Pryor Horse List with Graph Info

A B C D E F G H I J Body 1 Name Born Sex Color Markings Mane Number Dam Sire Notes 9.27 outside horse 2 Rigel Starr 2017 filly sorrel star 201701 Nova Hickok range 3 Ryden 2017 colt dark small star Jasmine Doc Tall healthy colt-very 4 Rio 2017 colt dun blaze 201702 Jacinta Garay pretty star strip tiny, good bone-nurses 5 Ruby 2017 filly ? snip Jewel He Who for a long time Morning 12.17 Jasper patiently 6 Reverie 2017 filly foal dun 201704 Hataali Star follows her tiny snip-no bars-few hairs for 7 Quasar 2016 colt grullo star 201601 Kitalpha Hickok short stepping a little? 8 Quahneah 2016 Filly dun blaze 201608 Washakie Baja Playful-tries to nurse Quanah 9 Parker 2016 colt grulla 201602 Halcyon Flint blue 10 Quillan 2016 filly roan small star 201607 Electra Galaxy 11 Quaid 2016 colt dark bay big star 201603 Greta Garcia blaze, b/r apart from rest joined 12 Quintasket 2016 filly chestnut stocking 201603 Hopi Duke w/he who 13 Quintana 2016 Filly grulla star 201606 Feldspar Mescalero star, many Holding back-going to be 14 Pax 2015 colt grulla stripes 201513 La Nina Unknown kicked out? 15 Prima 2015 filly red dun markings 2510 Nova Hickok reddish 16 Parry 2015 filly dun large star 201504 Fresia Hidalgo A B C D E F G H I J Body 1 Name Born Sex Color Markings Mane Number Dam Sire Notes dot star, 17 Penn 2015 filly black dot snip 201514 Audubon Hamlet dk 18 Phantom 2015 filly brown Star 210501 Icara Fools Crow bucking running high Banjo coyote spirits, low water 19 Patterson 2015 colt dun solid 201508 Gabrielle Casper catchment Innocente 20 Orielle -

The Base Colors: Black and Chestnut the Tail, Called “Foal Fringes.”The Lower Legs Can Be So Pale That It Is Let’S Begin with the Base Colors

Foal Color 4.08 3/20/08 2:18 PM Page 44 he safe arrival of a newborn foal is cause for celebration. months the sun bleaches the foal’s birth coat, altering its appear- After checking to make sure all is well with the mare and ance even more. Other environmental issues, such as type and her new addition, the questions start to fly. What gender quality of feed, also can have a profound effect on color. And as we is it? Which traits did the foal get from each parent? And shall see, some colors do change drastically in appearance with Twhat color is it, anyway? Many times this question is not easily age, such as gray and the roany type of sabino. Finally, when the answered unless the breeder has seen many foals, of many colors, foal shed occurs, the new color coming in often looks dramatical- throughout many foaling seasons. In the landmark 1939 movie, ly dark. Is it any wonder that so many foals are registered an incor- “The Wizard of Oz,” MGM used gelatin to dye the “Horse of a rect—and sometimes genetically impossible—color each year? Different Color,” but Mother Nature does a darn good job of cre- So how do you identify your foal’s color? First, let’s keep some ating the same spectacular special effects on her foals! basic rules of genetics in mind. Two chestnuts will only produce The foal’s color from birth to the foal shed (which generally chestnut; horses of the cream, dun, and silver dilutions must have occurs between three and four months of age) can change due to had at least one parent with that particular dilution themselves; many factors, prompting some breeders to describe their foal as and grays must always have one gray parent. -

Color Coat Genetics

Color CAMERoatICAN ≤UARTER Genet HORSE ics Sorrel Chestnut Bay Brown Black Palomino Buckskin Cremello Perlino Red Dun Dun Grullo Red Roan Bay Roan Blue Roan Gray SORREL WHAT ARE THE COLOR GENETICS OF A SORREL? Like CHESTNUT, a SORREL carries TWO copies of the RED gene only (or rather, non-BLACK) meaning it allows for the color RED only. SORREL possesses no other color genes, including BLACK, regardless of parentage. It is completely recessive to all other coat colors. When breeding with a SORREL, any color other than SORREL will come exclusively from the other parent. A SORREL or CHESTNUT bred to a SORREL or CHESTNUT will yield SORREL or CHESTNUT 100 percent of the time. SORREL and CHESTNUT are the most common colors in American Quarter Horses. WHAT DOES A SORREL LOOK LIKE? The most common appearance of SORREL is a red body with a red mane and tail with no black points. But the SORREL can have variations of both body color and mane and tail color, both areas having a base of red. The mature body may be a bright red, deep red, or a darker red appearing almost as CHESTNUT, and any variation in between. The mane and tail are usually the same color as the body but may be blonde or flaxen. In fact, a light SORREL with a blonde or flaxen mane and tail may closely resemble (and is often confused with) a PALOMINO, and if a dorsal stripe is present (which a SORREL may have), it may be confused with a RED DUN. -

EQUINE COAT COLORS and GENETICS by Erika Eckstrom

EQUINE COAT COLORS AND GENETICS By Erika Eckstrom Crème Genetics The cream gene is an incomplete dominant. Horse shows a diluted body color to pinkish-red, yellow-red, yellow or mouse gray. The crème gene works in an additive effect, making a horse carrying two copies of the gene more diluted towards a crème color than a horse with one copy of the gene. Crème genes dilute red coloration more easily than black. No Crème Genes One Crème Gene Two Crème Genes Black Smokey Black Smokey Crème A Black based horse with no "bay" A Black horse that received one copy A Black horse that received one copy gene, and no dilution gene, ranging of the crème dilution gene from one of the crème gene from both of its from "true" black to brown in of its parents, but probably looks no parents, possessing pink skin, blue eyes, and an orange or red cast to the appearance. different than any other black or brown horse. entire hair coat. Bay Buckskin Perlino A Black based horse with the "bay" Agouti gene, which restricts the A Bay horse that received one copy A Bay horse that received one copy of black to the mane, tail and legs of the crème dilution gene from its the crème gene from both of its (also called black "points") and no parents, giving it a diluted hair coat parents, and has pink skin, blue eyes, a ranging in color from pale cream, cream to white colored coat and a dilution gene. gold or dark "smutty" color, and has darker mane and tail (often orange or black "points". -

Captain of the Gray-Horse Troop, by Hamlin Garland 1

Captain of the Gray-Horse Troop, by Hamlin Garland 1 Captain of the Gray-Horse Troop, by Hamlin Garland Project Gutenberg's The Captain of the Gray-Horse Troop, by Hamlin Garland This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Captain of the Gray-Horse Troop Author: Hamlin Garland Release Date: August 18, 2010 [EBook #33458] Captain of the Gray-Horse Troop, by Hamlin Garland 2 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CAPTAIN OF THE *** Produced by Mary Meehan and The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) THE CAPTAIN OF THE GRAY-HORSE TROOP By HAMLIN GARLAND SUNSET EDITION HARPER & BROTHERS NEW YORK AND LONDON COPYRIGHT, 1901. BY THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY COPYRIGHT 1902. BY HAMLIN GARLAND [Illustration] CONTENTS I. A CAMP IN THE SNOW II. THE STREETER GUN-RACK III. CURTIS ASSUMES CHARGE OF THE AGENT IV. THE BEAUTIFUL ELSIE BEE BEE V. CAGED EAGLES Captain of the Gray-Horse Troop, by Hamlin Garland 3 VI. CURTIS SEEKS A TRUCE VII. ELSIE RELENTS A LITTLE VIII. CURTIS WRITES A LONG LETTER IX. CALLED TO WASHINGTON X. CURTIS AT HEADQUARTERS XI. CURTIS GRAPPLES WITH BRISBANE XII. SPRING ON THE ELK XIII. ELSIE PROMISES TO RETURN XIV. -

DNA Is Our Core Information About Coat Colours in Horses

Information about Coat Colours in horses Within the large number of coat colour factors three genetic features explain the major differences in coat colours. These are the Agouti Factor, the Red Factor (Extension locus) and the Cream Dilution Factor. In the table below, possible combinations are indicated: Genetic Factor Coat Colour Agouti Red Factor, Extension Cream Dilution locus Factor Black a/a E/E or E/e N/N Brown or Bay A/A or A/a E/E or E/e N/N Chestnut A/A, A/a or a/a e/e N/N Smoky black a/a E/E or E/e N/Cr Buckskin A/A or A/a E/E or E/e N/Cr Palomino A/A, A/a or a/a e/e N/Cr Smoky cream a/a E/E or E/e Cr/Cr Perlino A/A or A/a E/E or E/e Cr/Cr Cremello A/A, A/a or a/a e/e Cr/Cr The Agouti Factor encloses the following results: A/A In the hair, the black pigment is point shaped distributed. Basic colour is bay or brown in the absence of other modifying genes. A/a In the hair, the black pigment is point shaped distributed. Basic colour is bay or brown in the absence of other modifying genes. a/a Only recessive allele detected. Black pigment distributed uniformly. Basic colour is black in the absence of other modifying genes. The Red Factor (Chestnut) encloses the following results: e/e Only red factor detected.