Dyslexia and Dyscalculia Are the Same Thing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developmental Coordination Disorder and Dysgraphia

Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation Maëlle Biotteau, Jérémy Danna, Éloïse Baudou, Frédéric Puyjarinet, Jean-Luc Velay, Jean-Michel Albaret, Yves Chaix To cite this version: Maëlle Biotteau, Jérémy Danna, Éloïse Baudou, Frédéric Puyjarinet, Jean-Luc Velay, et al.. De- velopmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabil- itation. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Dove Medical Press, 2019, 15, pp.1873-1885. 10.2147/NDT.S120514. hal-02177153 HAL Id: hal-02177153 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02177153 Submitted on 8 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Maëlle Biotteau 1 Abstract: Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a common and well-recognized Jérémy Danna 2 neurodevelopmental disorder affecting approximately 5 in every 100 individuals worldwide. It Éloïse Baudou 3 has long been included in standard national and international classifications of disorders (especially Frédéric Puyjarinet 4 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). -

The Basics About the 3 D's: Learning Disabilities

THE BASICS ABOUT THE 3 D’S: LEARNING DISABILITIES Cathy Johnson, M.A., C.C.C, S.L.T Licensed Speech/Language Pathologist Structured Literacy Teacher Speech, Language and Learning Center Johnson Academy of Therapeutic Learning Disclosure Neither I nor any member of my immediate family has a financial relationship or interest (currently or within the past 12 months) with any proprietary entity producing health care goods or services consumed by, or used on, patients related to the content of this CME activity. I do not intend to discuss an unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device. Agenda ● Three types of learning disabilities: Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, and Dyscalculia ● Definitions ● Signs and symptoms ● Frequently co‐occurring disorders to be aware of: ADHD (30% of those with dyslexia have coexisting AD/HD) &/or APD Learning Disabilities • Problems with age appropriate reading, spelling, and/or writing • A learning disability is not about how smart a person is but more about how they process sounds and language • Most people diagnosed with learning disabilities have average to superior intelligence Definition of Dyslexia ● Dyslexia is no longer diagnosed with regard to an IQ discrepancy. ● We have known this from research that came out in the early 1990s (e.g., Siegel 1992). ● This was officially changed in the DSM‐5 (2013). Definition of Dyslexia- IDA definition average to above average intellectual ability with an unexpected difficulty in reading 1. Dyslexia is a language‐based learning disability. 2. Dyslexia is hereditary and lifelong. 3. Dyslexia is more common than many people think. 4. Before school starts, dyslexia may not be obvious. -

What This Means for You As a Special Educator/Service Provider

Anne Arundel County – Department of Special Education Technical Assistant Bulletin (revised July 2017) Specific Learning Disability; Including Dyslexia; Dysgraphia; Dyscalculia September 2019 Overall Emphasis and Purpose: Specific Learning Disability (SLD) is one of the 13 categories of disability recognized by the IDEA. SLD is the only disability category for which the IDEA establishes special evaluation procedures, in addition to the general procedures that are used for all students with disabilities. The definition of a SLD is “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding, or in using language spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations.” During the 2017 legislative session, a bill was passed authorizing schools to identify dyslexia, dysgraphia, or dyscalculia, as subcategories under the overarching SLD classification. What this means for you as a Special What the Special Educator/Service Educator/Service Provider: Provider needs to do if not already doing: • The identification of a SLD requires that the student • Ensure that school staff are supported in implementing exhibit a pattern of strengths and weaknesses in research and/or evidence-based intervention for any performance, achievement, or both, relative to age, student who is struggling. Progress monitoring is a key State approved grade level standards, or intellectual component of determining the effectiveness of the development, as a result of a comprehensive intervention prior to considering the possibility of a evaluation. disability under the IDEA. • A student identified with a specific learning disability, • The IEP team must consider exclusionary factors, such with or without dyslexia, dysgraphia, or dyscalculia, as a lack of appropriate education, intellectual must also exhibit educational impact and require disability, visual, hearing, or motor impairment, specialized instruction. -

Developmental Dyscalculia, Gender, and the Brain

510 ArchivesofDiseasein Childhood 1993; 68: 510-512 CURRENT TOPIC Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.68.4.510 on 1 April 1993. Downloaded from Developmental dyscalculia, gender, and the brain Varda Gross-Tsur, Orly Manor, Ruth S Shalev Background Aldenkamp reported that children in the 12-18 Developmental dyscalculia is a primary cognitive year age group had the most difficulties with disorder of childhood affecting the ability of an mathematics. 14 Seidenberg et al studied the otherwise intelligent and healthy child to learn academic achievement of 122 children ages 7-15 arithmetic.' Preliminary evidence indicates that years and found that this group was making less developmental dyscalculia is seen in 5-6% of academic progress than expected for their age normal children23 and is as prevalent as develop- and level of intelligence quotient (IQ); academic mental dyslexia or the attention deficit hyper- deficiencies were greatest in the area of arith- activity disorder.' One of the classifications of metic followed by spelling, reading comprehen- developmental dyscalculia subdivides dys- sion, and word recognition skills.'5 It has been calculia to: (1) alexia and agraphia for numbers, postulated that the 'speed factor type' oflearning (2) spatial dyscalculia, (3) anarithmetia (impair- disability in epileptic children was found to be ment of calculation per se), (4) attentional- related to underachievement in arithmetic.8 sequential dyscalculia, and (5) mixed type.4 Early age of seizure onset, age of the child, Rourke and Finlayson -

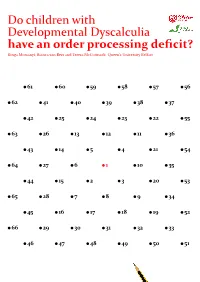

Do Children with Developmental Dyscalculia Havean Orderprocessing Deficit?

Do children with Developmental Dyscalculia have an order processing deficit? Kinga Morsanyi, Bianca van Bers and Teresa McCormack, Queen’s University Belfast 61 60 59 58 57 56 62 41 40 39 38 37 42 25 24 23 22 55 63 26 13 12 11 36 43 14 5 4 21 54 64 27 6 1 10 35 44 15 2 3 20 53 65 28 7 8 9 34 45 16 17 18 19 52 66 29 30 31 32 33 46 47 48 49 50 51 Contents Research highlights 2 Executive summary 5 The need for this research 7 Summary of aims 8 Methods 9 Key findings 14 Summary of key findings and recommendations 17 References 21 Acknowledgements 23 Appendix: Infographics 24 1 Research highlights Study 1: The prevalence of specific learning disorder in mathematics (SLDM or dyscalculia)1 This was the first prevalence study of SLDM since the publication of the new DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) diagnostic criteria in 2013. We considered data from 2,421 children (their level of intelligence and educational achievement in mathematics and English were recorded over several school years). We investigated the effects of gender, socio-economic status, special educational needs (other than issues related to mathematics), and whether the child spoke English as their first language on mathematics achievement. 5.7% of the sample was identified as having SLDM. Compared to earlier (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of SLDM was almost 6 times higher. A child was more than a 100 times more likely to receive a diagnosis of dyslexia than SLDM, although prevalence rates are expected to be similar. -

WORKING MEMORY & LEARNING DISABILITIES Working Memory Is

3/26/14 Working Memory is the FOUNDATION of Learning WORKING MEMORY & LEARNING DISABILITIES Tracy Packiam Alloway, PhD WM & Learning DisabiliKes DYSLEXIA (READING) • WHAT is the Core Deficit? • WHY is Working Memory is involved? • HOW to support Working Memory? 1 3/26/14 DYSLEXIA (READING) DYSLEXIA (READING) GENERAL STRATEGIES GENERAL STRATEGIES • Reduce working memory processing in • Keep track of their place in complex activities acKviKes – History Kmelines Rulers: reading & math problems – 45 + 98 45 +98 DYSLEXIA (READING) MATH (DYSCALCULIA) SPECIFIC STRATEGIES • Shorten acKviKes to reduce WM load – Sam worked with only 5 flowers – Repeated instructions just for him www.tracyalloway.com 2 3/26/14 Math (Dyscalculia) Math (Dyscalculia) GENERAL STRATEGIES GENERAL STRATEGIES • Use visual representaon to support working memory • Use visual representaon to support working memory • Algebra: negative exponents • Algebra: negative exponents www.tracyalloway.com Math (Dyscalculia) DCD (Motor) • Gross motor skills (large movements): SPECIFIC STRATEGIES – Poor balance: Riding a bicycle • Model the use of memory aids – Poor hand-eye co-ordination: Catching a ball & batting – Number lines • Fine motor skills (small movements): – Lack of manual dexterity: using cutlery, craft work, 1, 2, __, 4, __ playing musical instruments – Poor manipulative skills: Typing, handwriting and drawing, fastening clothes & tying shoelaces www.tracyalloway.com Alloway (2006) Working Memory & Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Psy Press 3 3/26/14 DCD (MOTOR) DCD (Motor) • Motor skills or Working Memory = Learning difficulties? • Two groups: – High Visual-Spatial Memory – Low Visual-Spatial Memory • Motor skills: Both groups will have low learning scores • Working Memory: Low VS Memory group will have lower learning scores • Low Visual-Spatial Memory group performed worse in Reading & Math – Even after accounting for IQ Alloway (2007) J. -

Similarities and Differences in the Learning Profiles of Adolescents

brain sciences Article Similarities and Differences in the Learning Profiles of Adolescents with SLD and SLI in Mathematics—A Preliminary Analysis Eleni Bonti 1,2,* , Afroditi Kamari 1, Maria Sofologi 3,4 , Sofia Giannoglou 1 , Georgia-Nektaria Porfyri 1 , Paraskevi Tatsiopoulou 1 , Georgios Kougioumtzis 5, Maria Efstratopoulou 6 and Ioannis Diakogiannis 1 1 First Psychiatric Clinic, “Papageorgiou” General Hospital, Ring Road Thessaloniki, N. Efkarpia, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54603 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (G.-N.P.); [email protected] (P.T.); [email protected] (I.D.) 2 Department of Education, School of Education, University of Nicosia, Nicosia 2417, Cyprus 3 Laboratory of Psychology, Department of Early Childhood Education, School of Education, University of Ioannina, 45110 Ioannina, Greece; [email protected] 4 Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University Research Center of Ioannina (URCI), 45110 Ioannina, Greece 5 Department of Turkish and Modern Asian Studies, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 10680 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 6 Department of Special Education (CEDU), United Arab Emirates University (UAEU), Al Ain 112612, United Arab Emirates; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Citation: Bonti, E.; Kamari, A.; Sofologi, M.; Giannoglou, S.; Porfyri, Abstract: SLI and SLD constitute two independent neurodevelopmental disorders, which frequently G.-N.; Tatsiopoulou, P.; cause challenges in the diagnosis process, especially due to their nature. This has caused disagreement Kougioumtzis, G.; Efstratopoulou, M.; among clinicians regarding their recognition as separate or overlapping disorders. The objective of Diakogiannis, I. Similarities and the study was to enlighten the path of valid diagnosis and intervention during adolescence when the Differences in the Learning Profiles of two disorders change their manifestation and overlap. -

Dyspraxia and Examinations

Dyspraxia and examinations The Equality Act (HMSO, 2010) states that specific learning differences such as dyslexia, dyspraxia / DCD (developmental coordination disorder) and dyscalculia are all classified as a disability under the terms of this Act. It is unlawful to discriminate against anyone on the basis of their disability. Individuals are entitled to receive reasonable adjustments to help them overcome their difficulties. Therefore reasonable adjustments which enable equality of opportunity during examinations/tests during a child’s school career must be considered. In the current SEND Code of practice (Jan 2015 ) page 17 paragraph xix states: Schools must make reasonable adjustments, including the provision of auxiliary aids and services, to ensure that disabled children and young people are not at a substantial disadvantage compared with their peers. This duty is anticipatory – it requires thought to be given in advance to what disabled children and young people might require and what adjustments might need to be made to prevent that disadvantage. The appropriate type of access arrangement will very much depend upon the results of testing, interview with the young person and their normal method of working. Teachers should remember that dyspraxia often occurs alongside other overlapping conditions such as dyslexia which will add to the difficulties experienced. It goes on to say (paragraph xxii) Where a child or young person is covered by SEN and disability legislation, reasonable adjustments and access arrangements should be considered as part of SEN planning and review. Where school governors are publishing information about their arrangements for disabled children and young people, this should be brought together with the information required under the Children and Families Act 2014. -

Learning Difficulties Information Guide – Numeracy

Learning Difficulties Information Guide Numeracy © State of Victoria (Department of Education and Training) 2019 Learning Difficulties Information Guide - Numeracy is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria (Department of Education and Training), indicate if changes were made and comply with the other licence terms, see: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International The licence does not apply to: • any images, photographs, trademarks or branding, including the Victorian Government logo and the DET logo; and • content supplied by third parties. Copyright queries may be directed to [email protected] Contents What is this guide? 4 Background 4 What is the difference between a learning disability and learning difficulty? 5 Legal responsibilities 6 Personalised learning and support planning 7 Numeracy learning difficulties 8 Why is numeracy important? 8 Characterising learning difficulties in numeracy 9 Identifying numeracy learning difficulties and dyscalculia 10 Subitising 11 Comparing approximate magnitudes 11 A three-phase maths assessment process 12 Numeracy intervention 14 Response to Intervention and numeracy learning difficulties 14 High Impact Teaching Strategies 15 Hallmarks of effective numeracy intervention 16 Adjustments for students with learning difficulties 18 Student support services 18 Case example 19 Learning difficulties and student wellbeing 21 Empowering students 21 Engaging with families 22 Bibliography and professional reading 23 APPENDIX 1 - HITS for numeracy 24 3 What is this guide? The Learning Difficulties Information Guide – Numeracy is a foundation for understanding learning Background difficulties in numeracy, including dyscalculia, and a guide for what teachers can do to support this cohort In June 2018, the Department of Education and of students. -

Acalculia and Dyscalculia

Neuropsychology Review pp628-nerv-452511 November 23, 2002 8:23 Style file version sep 03, 2002 Neuropsychology Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, December 2002 (C 2002) Acalculia and Dyscalculia , Alfredo Ardila1 3 and M´onica Rosselli2 Even though it is generally recognized that calculation ability represents a most important type of cognition, there is a significant paucity in the study of acalculia. In this paper the historical evolution of calculation abilities in humankind and the appearance of numerical concepts in child development are reviewed. Developmental calculation disturbances (developmental dyscalculia) are analyzed. It is proposed that calculation ability represents a multifactor skill, including verbal, spatial, memory, body knowledge, and executive function abilities. A general distinction between primary and secondary acalculias is presented, and different types of acquired calculation disturbances are analyzed. The association between acalculia and aphasia, apraxia and dementia is further considered, and special mention to the so-called Gerstmann syndrome is made. A model for the neuropsychological assessment of numerical abilities is proposed, and some general guidelines for the rehabilitation of calculation disturbances are presented. KEY WORDS: acalculia; dyscalculia; numerical knowledge; calculation ability. INTRODUCTION Acalculia is frequently mentioned in neurological and neuropsychological clinical reports, but research di- Calculation ability represents an extremely complex rected specifically to the analysis of acalculia -

Arithmetic Processing in Children with Dyscalculia: an Event-Related Potential Study

Arithmetic processing in children with dyscalculia: an event-related potential study Sonia Y. Cárdenas1, Juan Silva-Pereyra2, Belén Prieto-Corona2, Susana A. Castro-Chavira1 and Thalía Fernández1 1 Departamento de Neurobiología Conductual y Cognitiva, Instituto de Neurobiología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Querétaro, México 2 Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Tlalnepantla, Estado de México, México ABSTRACT Introduction: Dyscalculia is a specific learning disorder affecting the ability to learn certain math processes, such as arithmetic data recovery. The group of children with dyscalculia is very heterogeneous, in part due to variability in their working memory (WM) deficits. To assess the brain response to arithmetic data recovery, we applied an arithmetic verification task during an event-related potential (ERP) recording. Two effects have been reported: the N400 effect (higher negative amplitude for incongruent than for congruent condition), associated with arithmetic incongruency and caused by the arithmetic priming effect, and the LPC effect (higher positive amplitude for the incongruent compared to the congruent condition), associated with a reevaluation process and modulated by the plausibility of the presented condition. This study aimed to (a) compare arithmetic processing between children with dyscalculia and children with good academic performance (GAP) using ERPs during an addition verification task and (b) explore, among children with dyscalculia, the relationship between WM and ERP effects. Materials and Methods: EEGs of 22 children with dyscalculia (DYS group) and 22 children with GAP (GAP group) were recorded during the performance of Submitted 4 September 2019 an addition verification task. ERPs synchronized with the probe stimulus were Accepted 13 November 2020 computed separately for the congruent and incongruent probes, and included only 27 January 2021 Published epochs with correct answers. -

Utility of Testing for Apraxia and Associated Features in Dementia Samrah Ahmed,1 Ian Baker,2 Sian Thompson,3 Masud Husain,1,4 Christopher R Butler1

JNNP Online First, published on June 1, 2016 as 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312945 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312945 on 1 June 2016. Downloaded from Cognitive neurology RESEARCH PAPER Utility of testing for apraxia and associated features in dementia Samrah Ahmed,1 Ian Baker,2 Sian Thompson,3 Masud Husain,1,4 Christopher R Butler1 1Nuffield Department of ABSTRACT apraxia refers to difficulty pantomiming learned Clinical Neurosciences, Introduction Existing literature suggests that the actions such as brushing the teeth or combing the University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK presence or absence of apraxia and associated parietal hair; ideational apraxia describes an inability to 2Russell Cairns Unit, Oxford deficits may be clinically relevant in differential diagnosis carry out complex sequences of actions in everyday University Hospitals NHS Trust, of dementia syndromes. life, such as making a cup of tea.3 John Radcliffe Hospital, Aim This study investigated the profile of these features A survey of the existing literature reveals Oxford, UK 3 in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontotemporal dementia common observations of apraxia in amnestic Department of Clinical fi ’ Neurology, Oxford University (FTD) spectrum disorders, at rst presentation. Alzheimer s disease (AD). Apraxia is a diagnostic Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford, Methods Retrospective case note analysis was feature of amnestic AD, included in the UK undertaken in 111 patients who presented to the Oxford NINCDS-ADRDA (National Institute of 4 Department of Experimental Cognitive Disorders Clinic, Oxford, UK, including 29 Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Psychology, University of amnestic AD, 12 posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), 12 Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Oxford, John Radcliffe 45 Hospital, Oxford, UK logopenic primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA), 20 Association) criteria.