Learning Difficulties Information Guide – Numeracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dyslexia and Dyscalculia Are the Same Thing

Dyscalculia and Dyslexia Two different issues, or part of the same problem? By Tony Attwood C.Ed., B.A., M.Phil. Chairman of The Dyscalculia Group, First and Best in Education Ltd. Dyscalculia is noted as an unexpected difficulty that some people have in dealing with mathematical problems. At its simplest we may note a child whose age and intellect suggests that he or she will be able to undertake a certain range of skills, but who in effect is unable to handle maths problems that we would expect to be well within his or her grasp. As a general introduction to the topic we may note that according to the American Journal of Paediatrics in 2001 dyscalculic children have “Normal or advanced language and other skills, often good visual memory for the printed word, (and) poor mental maths ability often with difficulty in the use of money, such as balancing a chequebook, making change and tipping. Often there is a fear of money and its transactions and difficulty with maths processes (e.g. addition, subtraction, multiplication) and concepts (e.g. sequencing of numbers). There is sometimes poor retention and retrieval of concepts, or an inability to maintain a consistency in grasping maths rules, poor sense of direction, easy disorientation, as well as difficulty with reading maps, telling the time and grappling with mechanical processes, difficulty with abstract concepts of time and direction, schedules, keeping track of time and the sequence of past and future events.” These children make, “Common mistakes in working with numbers including number reversals and omissions,” (and) “May have difficulty learning musical concepts, following directions in sports that demand sequencing or rules, and keeping track of scores and players during games such as cards and board games. -

Theoretical Analysis of Threeresearch Apparatuses About Media and Information Literacy in France Jacques Kerneis, Olivier Le Deuff

Theoretical analysis of threeresearch apparatuses about media and information literacy in France Jacques Kerneis, Olivier Le Deuff To cite this version: Jacques Kerneis, Olivier Le Deuff. Theoretical analysis of threeresearch apparatuses about media and information literacy in France. Key Concepts and Key Issues in Learning, European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Aug 2012, Cadix, Spain. hal-01143562 HAL Id: hal-01143562 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01143562 Submitted on 20 Apr 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Theoretical analysis of threeresearch apparatuses about media and information literacy in France1 Jacques Kerneis 5 rue A. Camus, 29000 Quimper Résumé: 150-200 mots Abstract: In this article, we compare three projects about mapping digital-, media- and information literacyin France. For this study, we first used the concept of “apparatus” in Foucauldian (1977) and Agambenian sense (2009). After this analysis, we calledon Bachelard(1932) and his distinction between phénoménotechnique and phénoménographie. The first project began in 2006 around a professional association (Fadben: http://www.fadben.asso.fr/), with the main goal being to distinguish 64 main concepts in information literacy. This work is now completed, and we can observe it quietly through publications. -

Developmental Coordination Disorder and Dysgraphia

Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation Maëlle Biotteau, Jérémy Danna, Éloïse Baudou, Frédéric Puyjarinet, Jean-Luc Velay, Jean-Michel Albaret, Yves Chaix To cite this version: Maëlle Biotteau, Jérémy Danna, Éloïse Baudou, Frédéric Puyjarinet, Jean-Luc Velay, et al.. De- velopmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabil- itation. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Dove Medical Press, 2019, 15, pp.1873-1885. 10.2147/NDT.S120514. hal-02177153 HAL Id: hal-02177153 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02177153 Submitted on 8 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Maëlle Biotteau 1 Abstract: Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a common and well-recognized Jérémy Danna 2 neurodevelopmental disorder affecting approximately 5 in every 100 individuals worldwide. It Éloïse Baudou 3 has long been included in standard national and international classifications of disorders (especially Frédéric Puyjarinet 4 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). -

The Basics About the 3 D's: Learning Disabilities

THE BASICS ABOUT THE 3 D’S: LEARNING DISABILITIES Cathy Johnson, M.A., C.C.C, S.L.T Licensed Speech/Language Pathologist Structured Literacy Teacher Speech, Language and Learning Center Johnson Academy of Therapeutic Learning Disclosure Neither I nor any member of my immediate family has a financial relationship or interest (currently or within the past 12 months) with any proprietary entity producing health care goods or services consumed by, or used on, patients related to the content of this CME activity. I do not intend to discuss an unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device. Agenda ● Three types of learning disabilities: Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, and Dyscalculia ● Definitions ● Signs and symptoms ● Frequently co‐occurring disorders to be aware of: ADHD (30% of those with dyslexia have coexisting AD/HD) &/or APD Learning Disabilities • Problems with age appropriate reading, spelling, and/or writing • A learning disability is not about how smart a person is but more about how they process sounds and language • Most people diagnosed with learning disabilities have average to superior intelligence Definition of Dyslexia ● Dyslexia is no longer diagnosed with regard to an IQ discrepancy. ● We have known this from research that came out in the early 1990s (e.g., Siegel 1992). ● This was officially changed in the DSM‐5 (2013). Definition of Dyslexia- IDA definition average to above average intellectual ability with an unexpected difficulty in reading 1. Dyslexia is a language‐based learning disability. 2. Dyslexia is hereditary and lifelong. 3. Dyslexia is more common than many people think. 4. Before school starts, dyslexia may not be obvious. -

What This Means for You As a Special Educator/Service Provider

Anne Arundel County – Department of Special Education Technical Assistant Bulletin (revised July 2017) Specific Learning Disability; Including Dyslexia; Dysgraphia; Dyscalculia September 2019 Overall Emphasis and Purpose: Specific Learning Disability (SLD) is one of the 13 categories of disability recognized by the IDEA. SLD is the only disability category for which the IDEA establishes special evaluation procedures, in addition to the general procedures that are used for all students with disabilities. The definition of a SLD is “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding, or in using language spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations.” During the 2017 legislative session, a bill was passed authorizing schools to identify dyslexia, dysgraphia, or dyscalculia, as subcategories under the overarching SLD classification. What this means for you as a Special What the Special Educator/Service Educator/Service Provider: Provider needs to do if not already doing: • The identification of a SLD requires that the student • Ensure that school staff are supported in implementing exhibit a pattern of strengths and weaknesses in research and/or evidence-based intervention for any performance, achievement, or both, relative to age, student who is struggling. Progress monitoring is a key State approved grade level standards, or intellectual component of determining the effectiveness of the development, as a result of a comprehensive intervention prior to considering the possibility of a evaluation. disability under the IDEA. • A student identified with a specific learning disability, • The IEP team must consider exclusionary factors, such with or without dyslexia, dysgraphia, or dyscalculia, as a lack of appropriate education, intellectual must also exhibit educational impact and require disability, visual, hearing, or motor impairment, specialized instruction. -

Definitions of Adult Functional Literacy and Numeracy for SDG Indicator 4.6.1'

Definitions of adult functional literacy and numeracy for SDG indicator 4.6.1’ GAML6/WD/4 Prepared by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL) GAML6/WD/4 2 Definitions of adult functional literacy and numeracy for SDG indicator 4.6.1 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 Overview Recommendations INTRODUCTION 4 DEFINITIONS 4 Literacy Numeracy Functionality DATA COLLECTION 7 Current situation Expected situation in 2030 FIXING MINIMUM PROFICIENCY LEVELS FOR INDICATOR 4.6.1 10 Minimum proficiency level (MPL) Definition and new approach The strategy for defining indicator 4.1.1 Implications for indicator 4.6.1 Methodologies for linking PIAAC–PISA linking studies Policy linking STRATEGY FOR 2030 16 Supporting the implementation of direct assessments 16 The benefits of implementing mini-LAMP Supporting investigations for indirect measurements REFERENCES 21 ANNEX A: COUNTRIES WITH DIRECT ADULT SKILLS ASSESSMENT 23 GAML6/WD/4 3 Definitions of adult functional literacy and numeracy for SDG indicator 4.6.1 Executive summary Overview This paper presents points for discussion with regard to the strategy to improve assessment of the literacy and numeracy skills of youth and adults, as associated with UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 4.6.1, which calls on countries to report the ‘proportion of population in a given age group achieving at least a fixed level of proficiency in functional (a) literacy and (b) numeracy skills, by sex’. It comprises four parts and one annex: Part 1 outlines the definitions associated with literacy and numeracy in the context of SDG indicator 4.6.1; Part 2 looks at existing skills assessment surveys of youth and adult populations around the world; Part 3 addresses the implications of the new approach for ‘fixing’ the minimum proficiency levels (MPLs) which will be reported for Indicator 4.6.1; and Part 4 provides a broad sketch of a tentative strategy for 2030. -

Developmental Dyscalculia, Gender, and the Brain

510 ArchivesofDiseasein Childhood 1993; 68: 510-512 CURRENT TOPIC Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.68.4.510 on 1 April 1993. Downloaded from Developmental dyscalculia, gender, and the brain Varda Gross-Tsur, Orly Manor, Ruth S Shalev Background Aldenkamp reported that children in the 12-18 Developmental dyscalculia is a primary cognitive year age group had the most difficulties with disorder of childhood affecting the ability of an mathematics. 14 Seidenberg et al studied the otherwise intelligent and healthy child to learn academic achievement of 122 children ages 7-15 arithmetic.' Preliminary evidence indicates that years and found that this group was making less developmental dyscalculia is seen in 5-6% of academic progress than expected for their age normal children23 and is as prevalent as develop- and level of intelligence quotient (IQ); academic mental dyslexia or the attention deficit hyper- deficiencies were greatest in the area of arith- activity disorder.' One of the classifications of metic followed by spelling, reading comprehen- developmental dyscalculia subdivides dys- sion, and word recognition skills.'5 It has been calculia to: (1) alexia and agraphia for numbers, postulated that the 'speed factor type' oflearning (2) spatial dyscalculia, (3) anarithmetia (impair- disability in epileptic children was found to be ment of calculation per se), (4) attentional- related to underachievement in arithmetic.8 sequential dyscalculia, and (5) mixed type.4 Early age of seizure onset, age of the child, Rourke and Finlayson -

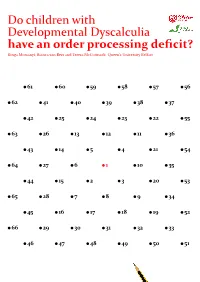

Do Children with Developmental Dyscalculia Havean Orderprocessing Deficit?

Do children with Developmental Dyscalculia have an order processing deficit? Kinga Morsanyi, Bianca van Bers and Teresa McCormack, Queen’s University Belfast 61 60 59 58 57 56 62 41 40 39 38 37 42 25 24 23 22 55 63 26 13 12 11 36 43 14 5 4 21 54 64 27 6 1 10 35 44 15 2 3 20 53 65 28 7 8 9 34 45 16 17 18 19 52 66 29 30 31 32 33 46 47 48 49 50 51 Contents Research highlights 2 Executive summary 5 The need for this research 7 Summary of aims 8 Methods 9 Key findings 14 Summary of key findings and recommendations 17 References 21 Acknowledgements 23 Appendix: Infographics 24 1 Research highlights Study 1: The prevalence of specific learning disorder in mathematics (SLDM or dyscalculia)1 This was the first prevalence study of SLDM since the publication of the new DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) diagnostic criteria in 2013. We considered data from 2,421 children (their level of intelligence and educational achievement in mathematics and English were recorded over several school years). We investigated the effects of gender, socio-economic status, special educational needs (other than issues related to mathematics), and whether the child spoke English as their first language on mathematics achievement. 5.7% of the sample was identified as having SLDM. Compared to earlier (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of SLDM was almost 6 times higher. A child was more than a 100 times more likely to receive a diagnosis of dyslexia than SLDM, although prevalence rates are expected to be similar. -

WORKING MEMORY & LEARNING DISABILITIES Working Memory Is

3/26/14 Working Memory is the FOUNDATION of Learning WORKING MEMORY & LEARNING DISABILITIES Tracy Packiam Alloway, PhD WM & Learning DisabiliKes DYSLEXIA (READING) • WHAT is the Core Deficit? • WHY is Working Memory is involved? • HOW to support Working Memory? 1 3/26/14 DYSLEXIA (READING) DYSLEXIA (READING) GENERAL STRATEGIES GENERAL STRATEGIES • Reduce working memory processing in • Keep track of their place in complex activities acKviKes – History Kmelines Rulers: reading & math problems – 45 + 98 45 +98 DYSLEXIA (READING) MATH (DYSCALCULIA) SPECIFIC STRATEGIES • Shorten acKviKes to reduce WM load – Sam worked with only 5 flowers – Repeated instructions just for him www.tracyalloway.com 2 3/26/14 Math (Dyscalculia) Math (Dyscalculia) GENERAL STRATEGIES GENERAL STRATEGIES • Use visual representaon to support working memory • Use visual representaon to support working memory • Algebra: negative exponents • Algebra: negative exponents www.tracyalloway.com Math (Dyscalculia) DCD (Motor) • Gross motor skills (large movements): SPECIFIC STRATEGIES – Poor balance: Riding a bicycle • Model the use of memory aids – Poor hand-eye co-ordination: Catching a ball & batting – Number lines • Fine motor skills (small movements): – Lack of manual dexterity: using cutlery, craft work, 1, 2, __, 4, __ playing musical instruments – Poor manipulative skills: Typing, handwriting and drawing, fastening clothes & tying shoelaces www.tracyalloway.com Alloway (2006) Working Memory & Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Psy Press 3 3/26/14 DCD (MOTOR) DCD (Motor) • Motor skills or Working Memory = Learning difficulties? • Two groups: – High Visual-Spatial Memory – Low Visual-Spatial Memory • Motor skills: Both groups will have low learning scores • Working Memory: Low VS Memory group will have lower learning scores • Low Visual-Spatial Memory group performed worse in Reading & Math – Even after accounting for IQ Alloway (2007) J. -

Five Components of Effective Oral Language Instruction

Five Components of Effective Oral Language Instruction 1 Introduction “Oral Language is the child’s first, most important, and most frequently used structured medium of communication. It is the primary means through which each individual child will be enabled to structure, to evaluate, to describe and to control his/her experience. In addition, and most significantly, oral language is the primary mediator of culture, the way in which children locate themselves in the world, and define themselves with it and within it” (Cregan, 1998, as cited in Archer, Cregan, McGough, Shiel, 2012) At its most basic level, oral language is about communicating with other people. It involves a process of utilizing thinking, knowledge and skills in order to speak and listen effectively. As such, it is central to the lives of all people. Oral language permeates every facet of the primary school curriculum. The development of oral language is given an importance as great as that of reading and writing, at every level, in the curriculum. It has an equal weighting with them in the integrated language process. Although the Curriculum places a strong emphasis on oral language, it has been widely acknowledged that the implementation of the Oral Language strand has proved challenging and “there is evidence that some teachers may have struggled to implement this component because the underlying framework was unclear to them” (NCCA, 2012, pg. 10) In light of this and in order to provide a structured approach for teachers, a suggested model for effective oral language instruction is outlined in this booklet. It consists of five components, each of which is detailed on subsequent pages. -

The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2012 The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks Donald Braman George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Dan M. Kahan Ellen Peters Maggie Wittlin Paul Slovic See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Donald Braman et. at., The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks, 2 Nature Climate Change 732 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Donald Braman, Dan M. Kahan, Ellen Peters, Maggie Wittlin, Paul Slovic, Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, and Gregory N. Mandel This article is available at Scholarly Commons: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/265 Published version (linked): Kahan, D.M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L.L., Braman, D. & Mandel, G. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change 2, 732-735 (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks Dan M. Kahan Ellen Peters Yale University The Ohio State University Maggie Wittlin Paul Slovic Lisa Larrimore Ouellette Cultural Cognition Project Lab Decision Research Cultural Cognition Project Lab Donald Braman Gregory Mandel George Washington University Temple University Acknowledgments. -

Dyscalculia in the Classroom

Practical ways to support dyslexic and dyscalculic learners with maths Judy Hornigold Maths Difficulties • Dyslexia? • Dyscalculia? • Maths Anxiety? Judy Hornigold Dyslexia • Phonological Awareness • Processing Speed • Memory • Organisation Judy Hornigold Mathematical Difficulties Dyslexics Experience • Sequencing • Processing Speed • Poor short term memory • Poor long term memory for retaining number facts and procedures, leading to poor numeracy skills • Reading word problems • Substituting names that begin with the same letter e.g. integer/integral, diameter/diagram • Remembering and retrieving specialised mathematical vocabulary • Copying errors • Frequent loss of place • Presentation of work on the page • Visual perception and reversals E.G. 3/E or 2/5 or +/x Strategies to help • Prompt cards • Aperture cards • Arrows/Colour to highlight direction • Encourage visualisation- CPA • Limit copying • More time • Scaffolding • Overlearning Judy Hornigold Dyscalculia Mathematics Disorder: "as measured by a standardised test that is given individually, the person's mathematical ability is substantially less than would be expected from the person’s age, intelligence and education. This deficiency materially impedes academic achievement or daily living“ DSM IV Judy Hornigold The National Numeracy Strategy DfES (2001) Dyscalculia is a condition that affects the ability to acquire arithmetical skills. Dyscalculic learners may have difficulty understanding simple number concepts, lack an intuitive grasp of numbers, and have problems learning number