(TCV) Immunization Campaign in Karachi, Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dispositifs of (Dis)Order: Gangs, Governmentality and the Policing of Lyari, Pakistan Adeem Suhail

Dispositifs of (Dis)Order: Gangs, governmentality and the policing of Lyari, Pakistan Adeem Suhail Abstract: At a moment when the violence of policing has found its locus in the bureaucratic institutions of ‘the police’, anthropology offers a more expansive idea of policing as a social function, articulated through multiple social forms, and crucial to hierarchical orders. This article draws on the idea of the dispositif to offer a processual model for understanding how non-state violence abets the maintenance of social order. Exploring the limits of biopolitics and drawing on ethnographic evidence, it uses the case of gang activity in Lyari, Pakistan, to show how gangsters maintained, rather than disrupt, the dominant social order in the city. Furthermore, it shows that those who challenged the inherently violent and exploitative order implemented by the gangs and the city's political elite were prime targets of public violence wielded by law and outlaw working together as a dispositif. Introduction The policeman who collected him from the recycling depot did not offer any explanations which made Babu Maheshwari apprehensive. Things became clearer when a few blocks away they arrived at the drainage nala. Babu saw the boy floating face-down in the murky waters amidst the thick sludge of excreta, plastics, chemicals, and once-desired objects that form Karachi’s daily discharge. This mundanely repugnant ecology had claimed and begun consuming the boy. Babu, a veteran municipal waste worker hailing from the ex-untouchable Dalit communities of coastal Sind, was brung, once more, to be the instrument that reclaimed the body, as a once-desired object, now discarded by city into its rivers of shit. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

DC Valuation Table (2018-19)

VALUATION TABLE URBAN WAGHA TOWN Residential 2018-19 Commercial 2018-19 # AREA Constructed Constructed Open Plot Open Plot property per property per Per Marla Per Marla sqft sqft ATTOKI AWAN, Bismillah , Al Raheem 1 Garden , Al Ahmed Garden etc (All 275,000 880 375,000 1,430 Residential) BAGHBANPURA (ALL TOWN / 2 375,000 880 700,000 1,430 SOCITIES) BAGRIAN SYEDAN (ALL TOWN / 3 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 SOCITIES) CHAK RAMPURA (Garision Garden, 4 275,000 880 400,000 1,430 Rehmat Town etc) (All Residential) CHAK DHEERA (ALL TOWN / 5 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIETIES) DAROGHAWALA CHOWK TO RING 6 500,000 880 750,000 1,430 ROAD MEHMOOD BOOTI 7 DAVI PURA (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) 275,000 880 350,000 1,430 FATEH JANG SINGH WALA (ALL TOWN 8 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) GOBIND PURA (ALL TOWNS / 9 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIEITIES) HANDU, Al Raheem, Masha Allah, 10 Gulshen Dawood,Al Ahmed Garden (ALL 250,000 880 350,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) JALLO, Al Hafeez, IBL Homes, Palm 11 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 Villas, Aziz Garden etc KHEERA, Aziz Garden, Canal Forts, Al 12 Hafeez Garden, Palm Villas (ALL TOWN 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) KOT DUNI CHAND Al Karim Garden, 13 Malik Nazir G Garden, Ghous Garden 250,000 880 400,000 1,430 (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) KOTLI GHASI Hanif Park, Garision Garden, Gulshen e Haider, Moeez Town & 14 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 New Bilal Gung H Scheme (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Al Wadood Garden (ALL 15 225,000 880 500,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Ring Road Par (ALL TOWN 16 75,000 880 200,000 -

TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-E - Faisal

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Karachi TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-e - Faisal. 0316-9992201 2 Karachi TCS Office Main Head 101-104 CAA Club Road Near Hajj Tarminal - 3 0316-9992202 3 Karachi TCS Office Malir Cantt Shop#180 S-13 Cantt Bazar, Malir Cantonement, Karachi 0316-9992204 4 Karachi TCS Office Malir Court Shop # G-14 Al Raza Sq. New Malir City Near Malir Court 0316-9992207 Shop # 3Haq Baho shopping Center Gulshan e Hadeed Ph.1 Gulshan e 5 Karachi TCS Office Gulshan-E-Hadeed 0316-9992213 Hadeed 6 Karachi TCS Office Korangi No. 4 Shop # 10, Abbasi Fair Trade Centre, Korangi # 4 Opp. KMC Zoo 0316-9992215 7 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN Chowrangi Shop A 1/30, block No 5. Haider plaza gulshan-e-Iqbal Karachi 0316-9992230 8 Karachi TCS Office GULISTAN-E-JOHAR Shop # Saima Classic Rashid Minas Road Near Johar More 0316-9992231 9 Karachi TCS Office HYDRI Shop # B-13, Al Bohran Circle, Block-B, North Nazimabad. 0316-9992232 10 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN-E-IQBAL Shop # 06, Plot # B-74 Shelzon Center BI.15 Opp. Usmania Restrent 0316-9992234 11 Karachi TCS Office ORANGI TOWN Banaras Town, Sector 8, Orangi Town Karachi Opp. Banaras Town Masjid 0316-9992236 12 Karachi TCS Office S.I.T.E Shop # 5, SITE Shopping Centre, Manghopir Rd. Opp. MCB SITE Br. 0316-9992237 13 Karachi TCS Office NIPA CHOWRANGI Shop # A -8 KDA Overseas apartment 0316-9992241 S 5 Noman Arcade Bl. 14 Gulshan-e-Iqbal Near Mashriq Centre Sir 14 Karachi TCS Office Mashriq Center 0316-9992250 suleman shah Rd. -

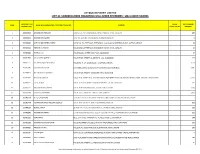

LAHORE HI Ill £1

Government of Pakistan Revenue Division Federal Board of Revenue ***** Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019. NOTIFICATION (Income Tax) S.R.O. 9^ (I)/2019.- In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 121(I)/2019 dated the Is' February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in columns (3) and (4) of the Table below in respect of areas or categories of Lahore specified in column (2) thereof. (2) The value for residential and commercial superstructure shall be — (a) Rs.1500 per square foot if the superstructure is upto five years old; and (b) Rs.1000 per square foot if the superstructure is more than five years old. (3) In order to determine the value of constructed property, the value of open plot shall be added to the value worked out at sub-paragraph (2) above. (4) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. LAHORE .-r* ALLAMA IQBAL TOWN S. Area Value of Residential Value of No property per maria Commercial (in Rs.) property per maria (in Rs.) HI ill £1 (41 1 ABDALIAN COOP SOCIETY 852,720 1,309,000 2 ABADI MUSALA MOUZA MUSALA 244,200 447,120 3 ABID GARDEN ABADI MUSALA 332,970 804,540 4 ADJOINING CANAL BANK ALL 564,960 1,331,000 SOCIETY MOUZA KANJARAN 5 ADJOINING CANAL BANK ALL 746,900 1,326,380 SOCIETY MOUZA IN SHAHPUR KHANPUR 6 AGRICHES COOP SOCIETY 570,900 1,039,500 7 AHBAB COLONY 392,610262,680 8 AHMAD SCHEME NIAZ BAIG 390,443 800,228 -

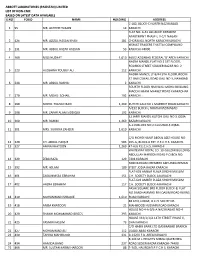

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Pwd14-214.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN PAKISTAN PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT ***** NO.EE/KCCD-III/AB/231 Karachi, dated, 29th March 2021. INVITATION TO BID The Executive Engineer, Karachi Central Civil Division No.III, Pak PWD, Karachi, re-invites sealed tenders, on percentage rate basis for the works tabulated hereunder, from the Contractors / Firms registered with Income Tax (who are Active on Taxpayers List & non-defaulter of Federal Board of Revenue) & having valid licence of Pakistan Engineering Council, in appropriate category & field of specializations. 2. A complete set of Bidding Documents containing detailed terms and conditions may be purchased by an interested eligible bidder on submission of a written application supported with requisite documents from the office of the undersigned latest by 20-04-2021 upon payment of a non-refundable fee as shown against each. 3. Bidders will submit two sealed envelopes simultaneously, one containing the Technical Proposal and the other Financial Proposals, duly marked separately with page numbering, signature & rubber stamp, and enclosed together in an outer single envelope, in consonance with Rule-36(b) of PPRA 2004 except for the works listed at Serial No.2, 7, 9 & 23 based on Single Stage Single Envelope procedure in consonance with ibid Rule-36(a) in single envelope with the mandatory documents as mentioned here-in-under, so as to reach the office of the undersigned on 21-04-2021 before 12:00 noon, which will be opened at 12:30 p.m. on the same day in the presence of bidders / representatives who choose to attend. 4. In accordance with PPRA Rule-25; Bid Security i.e. -

List of Unclaimed Shares and Dividend

ATTOCK REFINERY LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS REGARDING UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS / UNCLAIMED SHARES FOLIO NO / CDC SHARE NET DIVIDEND S/NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDER / CERTIFICATE HOLDER ADDRESS ACCOUNT NO. CERTIFICATES AMOUNT 1 208020582 MUHAMMAD HAROON DASKBZ COLLEGE, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, PHASE-VI, D.H.A., KARACHI 450 2 208020632 MUHAMMAD SALEEM SHOP NO.22, RUBY CENTRE,BOULTON MARKETKARACHI 8 3 307000046 IGI FINEX SECURITIES LIMITED SUIT # 701-713, 7TH FLOOR, THE FORUM, G-20, BLOCK 9, KHAYABAN-E-JAMI, CLIFTON, KARACHI 15 4 307013023 REHMAT ALI HASNIE HOUSE # 96/2, STREET # 19, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, DHA-6, KARACHI. 15 5 307020846 FARRUKH ALI HOUSE # 246-A, STREET # 39, F-11/3, ISLAMABAD 67 6 307022966 SALAHUDDIN QURESHI HOUSE # 785, STREET # 11, SECTOR G-11/1, ISLAMABAD. 174 7 307025555 ALI IMRAN IQBAL MOTIWALA HOUSE NO. H-1, F-48-49, BLOCK - 4, CLIFTON, KARACHI. 2,550 8 307026496 MUHAMMAD QASIM C/O HABIB AUTOS, ADAM KHAN, PANHWAR ROAD, JACOBABAD. 2,085 9 307028922 NAEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI HOUSE # 429, STREET # 4, SECTOR # G-9/3, ISLAMABAD. 7 10 307032411 KHALID MEHMOOD HOUSE # 10 , STREET # 13 , SHAHEEN TOWN, POST OFFICE FIZAI, C/O MADINA GERNEL STORE, CHAKLALA, RAWALPINDI. 6,950 11 307034797 FAZAL AHMED HOUSE # A-121,BLOCK # 15,RAILWAY COLONY , F.B AREA, KARACHI 225 12 307037535 NASEEM AKHTAR AWAN HOUSE # 183/3 MUNIR ROAD , LAHORE CANTT LAHORE . 1,390 13 307039564 TEHSEEN UR REHMAN HOUSE # S-5, JAMI STAFE LANE # 2, DHA, KARACHI. 3,475 14 307041594 ATTIQ-UR-REHMAN C/O HAFIZ SHIFATULLAH,BADAR GENERALSTORE,SHAMA COLONY,BEGUM KOT,LAHORE 7 15 307042774 MUHAMMAD NASIR HUSSAIN SIDDIQUI HOUSE-A-659,BLOCK-H, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI. -

Public and Private Control and Contestation of Public Space Amid Violent Conflict in Karachi

Public and private control and contestation of public space amid violent conflict in Karachi Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan Working Paper Urban Keywords: November 2015 Urban development, violence, public space, conflict, Karachi About the authors Published by IIED, November 2015 Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Noman Ahmed: Professor and Chairman, Department of Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan. 2015. Architecture and Planning at NED University of Engineering Public and private control and contestation of public space amid and Technology in Karachi. Email – [email protected] violent conflict in Karachi. IIED Working Paper. IIED, London. Bushra Owais Siddiqui: Young architect in private practice in http://pubs.iied.org/10752IIED Karachi. Email – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-78431-258-9 Dure Shahwar Khalil: Young architect in private practice in Karachi. Email – [email protected] Printed on recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Sana Tajuddin: Lecturer and Coordinator of Development Studies Programme at NED University, Karachi. Email – sana_ [email protected] Donald Brown: IIED Consultant. Email – donaldrmbrown@gmail. com Gordon McGranahan: Principal Researcher, Human Settlements Group, IIED. Email – [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements Group The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of Africa, Asia -

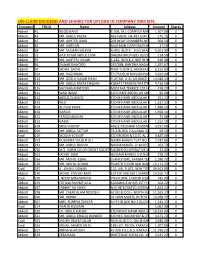

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Male / Co-Education) and Male Head of Institution at Ssc Level Upto 14-07-2021

1 LIST OF AFFILIATED INSTITUTIONS WITH STATUS (MALE / CO-EDUCATION) AND MALE HEAD OF INSTITUTION AT SSC LEVEL UPTO 14-07-2021 Inst Inst Principal S.No Inst Adress Gender Principal Name Phone No Principal Mobile No level Code Gender Angelique School, St.No.81, Embassy 051-2831007-8, 1. SSC 1002 Co-Education Maj (R) Nomaan Khan MALE 0321-5007177 Road, G-6/4, Islamabad 0321-5007177 Sultana Foundation Boys High School, 2. SSC 1042 Farash Town, Lehtrar Road (F.A), MALE WASEEM IRSHAD MALE 051-2618201 (Ext 152) 0315-7299977 Islamabad Scientific Model School, 25-26, Humak 051-4491188 , 3. SSC 1051 Co-Education KHAWAJA BASHIR AHMAD MALE 0345-5366348 (F.A), Islamabad 0345-5366348 Fauji Foundation Model School, Chak Wing Cdre Muhammad Laeeq 051-2321214, 4. SSC 1067 Co-Education MALE 0320-5635441 Shahzad Campus (F.A), Islamabad. Akhtar 0321-4044282 Academy of Secondary Education, Nai 051-4611613, 5. SSC 1070 Abadi G.T Road, Rewat (F.A), Co-Education Mr. AZHAR ALI SHAH MALE 0314-5136657 0314-5136657 Islamabad National Public Secondary School, G. 051-4612166, 6. SSC 1077 Co-Education IRFAN MAHMOOD MALE 03005338499 T Road, Rewat (F.A), Islamabad 0300-5338499 National Special Education Centre for 9260858, 7. SSC 1080 Physically Handicapped Children, G- Co-Education Islam Raziq MALE 0333-0732141 9263253 8/4, Islamabad Oxford High School, 413, Street No 43, 8. SSC 1083 Co-Education Lt. Col. Zafar Iqbal Malik (Retd) MALE 051-2253646 0321-5010789 Sector G-9/1, Islamabad Rawat Residential College, college 9. SSC 1090 Co-Education Tanzeela Malik Awan MALE 051-2516381 03465296351 Road, Rawat (F.A), Islamabad Sir Syed Ideal School System, House 10. -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study.