A Graduate Recital in Conducting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnificat: Vocal Score Free

FREE MAGNIFICAT: VOCAL SCORE PDF John Rutter | 88 pages | 01 Aug 1991 | Oxford University Press | 9780193380370 | English, Latin | Oxford, United Kingdom Vocal Score for Rutter Magnificat : Choraline For soprano or mezzo-soprano Magnificat: Vocal Score, SATB chorus and either full orchestra or chamber orchestra. Minimum recommended string forces for the chamber ensemble are 2. This edition is a publication of Oxford University Press. Full scores, vocal scores, and instrumental parts are available on hire through Oxford University Press. Home Music scores and recordings. John Rutter Magnificat. Add to wishlist. Feedback Be the first to give feedback on this product. Proceed to purchase. Additional product information. He first came to notice as a composer during his student years; much of his early work consisted of church music and other choral pieces including Christmas carols. From —79 he was Director of Music at his alma mater, Clare College, and directed the college chapel choir in various recordings and broadcasts. Since he has divided his time between composition and conducting. Today his compositions, including such concert-length works as RequiemMagnificat Magnificat: Vocal Score, Mass of the ChildrenThe Gift of Lifeand Visions are performed around the world. His music has featured in a number of British royal Magnificat: Vocal Score, including the two most recent royal weddings. In he formed his Magnificat: Vocal Score choir the Cambridge Singers, with whom he has made numerous Magnificat: Vocal Score, and he appears regularly in several countries as guest conductor and choral ambassador. Personal details. You have to be logged in to write a feedback. Magnificat: Vocal Score questions about this work There are no questions and answers available so far or you were unable to find an answer to your specific question about this work? Then click here and send your specific questions to our Customer Services! Related products. -

Grand Music Gracious Word

Grand Music Gracious Word JULY 2012 / YEAR B Sing For Joy® is a production of St. Olaf College. by Pastor Bruce Benson, host f you look up the etymology the turns and tumbles of human society, and we of the English word chorus can all name at least a hundred reasons not to be Ior choir, you will be in- joyful. But I think it is safe to say that as long formed that it comes from the Latin chorus which as the Biblical message of grace, love, dignity, comes from the older Greek word χορός or χῶρος forgiveness is proclaimed among people there will (choros.) The Greek word originally applied to be joy, and where there is joy (if Plato is right!) a circle dance or singing dance in a circle. That there will very likely be choruses. Therefore, at makes sense. Even for a choir of singers who have least in the church, option 1) above seems far been instructed (as I was as a youth,) “Don’t move more likely. anything except your mouth!” the act of sing- ing together is really a kind of dance. The voices This is not to say that we can simply take the must learn to dance with each other. No stepping future of the church choir for granted; we cannot. on anyone else’s musical toes; let your movements But it is to say that every assembly of people complement each other. gathered around the Gospel will feel a tug not just to listen to a chorus but to be a chorus. -

Download CD Booklet

ASS of the M HILDREN Cand other sacred music by JOHN RUTTER 2 3 institution of special significance to me. I will sing with the spirit (1994) is dedicated to MASS of the CHILDREN and other sacred music another institution, the Royal School of Church Music, who requested a simple anthem to serve as a theme song for their anniversary appeal. Mass of the Children was written in late 2002 and early 2003. The occasion of its first The final three pieces on the album form a group insofar as they are all for choir without performance in February 2003 was a concert in New York’s Carnegie Hall involving orchestra and on a more demanding level chorally. Musica Dei donum (1998), which has children’s choir, adult choir, soprano and baritone soloists, and orchestra. I had always wanted an important part for solo flute, is a setting of an anonymous text first set by Lassus in 1594 to write a work combining children’s choir with adult performers, not only because I find the that speaks of the power of music to draw, to soothe, and to uplift. Originally written for the sound of children’s voices irresistible but also because I wanted to repay a debt. As a boy choir of Clare College, this piece was subsequently included in A Garland for Linda, a cycle of soprano in my school choir I had been thrilled whenever our choir took part in adult works nine choral pieces by different composers in memory of Linda McCartney. I my Best- with children’s choir parts, such as the Mahler Third Symphony and the Britten War Requiem, Beloved’s am (2000) was written for the BBC Singers and first performed by them at a con- and years later I remembered this experience and wanted to write something that would give cert in Canterbury Cathedral on the theme of the seven sacraments. -

Download CD Booklet

John Rutter writes . impressed by the ease with which we came together musically, and by coincidence I was shortly afterwards asked by a US-based record company to make an album of my church music with hen I formed the Cambridge Singers in the early 1980s as a professional mixed the Gloria as the centrepiece, so the group was assembled once again to make the recording. chamber choir with recording rather than public performance as its principal focus, The Gloria album, released in 1984, marked the recording début of the Cambridge Singers. Wthe idea was a new one, and I never dreamed that we would still be recording – albeit Its unexpected success encouraged us to continue, and the Fauré Requiem, in its hitherto with changing though still Cambridge-leaning membership – thirty years later. little-known chamber version which I had edited from the composer’s manuscript, soon The seeds of the idea were sown during my days in the late 1970s as Director of Music at followed; it won a Gramophone magazine award. Through no one’s fault, there were constraints Clare College, Cambridge. It was an exciting period of change in the choral life of Cambridge and obstacles with both the labels to which these two recordings were contracted, and it seemed University: in 1972 three of our 25 or so men’s colleges, including Clare, began to admit women like the right moment to start a new record label as a permanent home for me and the students for the first time in the university’s 750-year history. -

Choral Music

SHOWSTOPPERS INTERNATIONAL INVITATIONAL AT DISNEYLAND@ PARK Anaheim, CA / April 17-20, 1997 KEYNOTE CHORAL FESTIVAL SERIES NASHVILLE CHORAL FESTIVAL Nashville, TN / April 17-20, 1997 KEYNOTE CHORAL FESTIVAL SERIES MANHATTAN CHORAL FESTIVAL New York, NY / May 1-4, 1997 CHILDREN IN HARMONY CHORAL FESTIVAL Orlando, FL / May 22-25, 1997 !lew! CHILDREN'S CELEBRATION SHOWSTARTERS CHORAL FESTIVAL SHO\,T CHOIR WORKSHOPS Anaheim, CA / June 26-29, 1997 Coming to an area near you ... September - November 1996 CONCERT TOURS Domestic & International/Year Round CHILDREN'S HOLIDAY CHORAL FESTIVAL AMERICA SINGS! FESTIVALS Orlando, FL / December 5-8, 1996 Los Angeles, CA / March 21-22, 1997 Orlando, FL / April 4-5, 1997 MEN OF SONG SHOWCASE Pittsburgh, PA / April 25-26, 1997 AT WALT DISNEY \VORLD@ RESORT Chicago, IL / May 9-10, 1997 Lake Buena Vista, FL February 27 - March 2, 1997 MAGIC MUSIC DAYS AT WALT DISNEY WORLD RESORT@ SHOWSTOPPERS & DISNE\'LlLND@PARK INTERNATIONAL INVITATIONAL Lake Buena Vista, FL / Anaheim, CA AT WALT DISNEY WORLD@ RESORT Year Round Lake Buena Vista, FL / March 13 -16, 1997 SHOWSTOPPERS NATIONAL --f!W- SHOW CHOIR INVITATIONAL I-= -::. --::. Chicago, IL / March 20-23, 1997 KEYNOTE ARTS ASSOCL\TES KEYNOTE ARTS ASSOCIATES COLLEGIATE 1637 E. ROBINSON ST. SHOWCASE INVITATIONAL ORLANDO, FL 32803 AT \VJ-\LT DISNEY \"X"TORLD@ RESORT Lake Buena Vista, FL / April 10-13, 1997 T407-897-8181 F407-897-8184 TOLL FREE 800-522-2213 KEYNOTE CHORAL FESTIVAL SERIES EMAIL [email protected] CHICAGO CHORAL FESTIVAL Chicago, IL / April 10-13, 1997 Official Publication of the American Choral Directors Association Volume Thirty-seven Number One AUGUST 1996 CHORALJO John Silantien Barton L.Tyner Jr. -

Grand Music Gracious Word

Grand Music Gracious Word JULY 2015 / YEAR B Sing For Joy® is a production of St. Olaf College. “My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness.” by Pastor Bruce Benson, host his past month I accepted an enjoyable assign- between strength — let’s call it power — and gentle- ment to serve as narrator with an all-volunteer ness in the performance of music can help us under- Tcommunity orchestra performing a composi- stand Paul’s point. We all, of course, enjoy hearing a tion for orchestra and spoken word. Needless to say, large choir or orchestra cranking up the volume and it took us more than one rehearsal to achieve a good sending music like a wave of sound washing over us. balance between orchestra and narration. Orchestra, It is exhilarating. And yet ... when that same power- voice and sound system all needed tweaking and fine- ful ensemble hushes to a barely audible pianissimo, it tuning to make music together. And each has limits. is enough to make us hold our breath. It is, to para- At the final rehearsal the conductor said, “We aren’t phrase Paul, almost as if strength (or power) is made a large enough orchestra to play as softly as I would perfect in that softness. like.” To be sure, there is a difference between gentleness and At first that sounds strange. It is certainly counter- weakness, at least in the way we normally use those intuitive. Shouldn’t it be more, not less, difficult for a words. But perhaps just as often, “weakness” is a label large ensemble to play sensitive pianissimo sections? given inappropriately to gentleness. -

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-Ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017 Compact Discs 2L Records Under The Wing of The Rock. 4 sound discs $24.98 2L Records ©2016 2L 119 SACD 7041888520924 Music by Sally Beamish, Benjamin Britten, Henning Kraggerud, Arne Nordheim, and Olav Anton Thommessen. With Soon-Mi Chung, Henning Kraggerud, and Oslo Camerata. Hybrid SACD. http://www.tfront.com/p-399168-under-the-wing-of-the-rock.aspx 4tay Records Hoover, Katherine, Requiem For The Innocent. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4048 681585404829 Katherine Hoover: The Last Invocation -- Echo -- Prayer In Time of War -- Peace Is The Way -- Paul Davies: Ave Maria -- David Lipten: A Widow’s Song -- How To -- Katherine Hoover: Requiem For The Innocent. Performed by the New York Virtuoso Singers. http://www.tfront.com/p-415481-requiem-for-the-innocent.aspx Rozow, Shie, Musical Fantasy. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4047 2 681585404720 Contents: Fantasia Appassionata -- Expedition -- Fantasy in Flight -- Destination Unknown -- Journey -- Uncharted Territory -- Esme’s Moon -- Old Friends -- Ananke. With Robert Thies, piano; The Lyris Quartet; Luke Maurer, viola; Brian O’Connor, French horn. http://www.tfront.com/p-410070-musical-fantasy.aspx Zaimont, Judith Lang, Pure, Cool (Water) : Symphony No. 4; Piano Trio No. 1 (Russian Summer). 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4003 2 888295336697 With the Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Winograd, violin; Peter Wyrick, cello; Joanne Polk, piano. http://www.tfront.com/p-398594-pure-cool-water-symphony-no-4-piano-trio-no-1-russian-summer.aspx Aca Records Trios For Viola d'Amore and Flute. -

The-John-Rutter-Christmas-Album

HIS ALBUM GATHERS TOGETHER most of the carols I have Tcomposed over the years, plus a sprinkling of my arrangements of traditional carols, grouped to form a programme which narrates, reflects upon, and celebrates the Christmas story. The I have always enjoyed carols ever since I first sang them as a member of my school choir, and it was not long before I began to write carols of my own— in fact my first two published compositions, written in my teens, were the John Rutter Nativity carol and the Shepherd’s pipe carol. This was more subversive than it sounds: at the time, the only officially approved style of composition for a classically-trained music student was post-Webernian serialism, which never appealed to me much, and writing Christmas carols was an undercover way of Christmas slipping a tune or two into circulation at a time of year when music critics are generally on vacation. No one seemed to mind, so from time to time I have continued to write and arrange carols, encouraged by Sir David Willcocks, my Album senior co-editor on several volumes of the Carols for Choirs series. For any musician involved in choral music, Christmas is an especially joyous time, and I am indeed happy that it has played a part in my musical life for so many years. JOHN RUTTER 2 3 The John Rutter Christmas Album 9 Star carol (2' 50") The Cambridge Singers • The City of London Sinfonia Words and music: John Rutter with Stephen Varcoe (baritone) 10 Candlelight carol (4' 06") Words and music: John Rutter directed by John Rutter 11 Total playing time: 78' 05" Shepherd’s pipe carol (2' 54") Words and music: John Rutter Prologue 12 Christmas lullaby (4' 04") 1 Wexford Carol (3' 58") Irish traditional carol Words and music: John Rutter arranged by John Rutter 13 Dormi, Jesu (4' 35") Baritone solo: Stephen Varcoe Words: medieval, and S. -

View PDF Editionarrow Forward

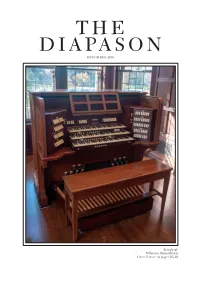

THE DIAPASON DECEMBER 2018 Stoneleigh Villanova, Pennsylvania Cover feature on pages 26–28 ANTHONY & BEARD ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO PETER RICHARD CONTE CONTE & ENNIS DUO LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD SIMON THOMAS JACOBS MARTIN JEAN HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE LOUPRETTE & GOFF DUO ROBERT MCCORMICK BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAéL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN ROBIN & LELEU DUO BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH JOSHUA STAFFORD THOMAS GAYNOR 2016 2017 LONGWOOD GARDENS ST. ALBANS WINNER WINNER IT’S ALL ABOUT THE ART ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ 860-560-7800 ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚͬWŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Ninth Year: No. 12, ‘Tis the season Whole No. 1309 This issue will likely arrive in your mailbox (or email box) DECEMBER 2018 shortly after Thanksgiving. The staff of The Diapason hopes Established in 1909 you had a pleasant and restful holiday. Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 As we now move into the busy season where many of us are 847/954-7989; [email protected] dealing with special events for Advent and Christmas, we wish www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, you again the best of this special time. We remind you in this the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music gift-giving season that a subscription to The Diapason makes of Minnesota, Minneapolis, a multi-year project recently com- the perfect gift for friends and students. Through the end of pleted by Foley-Baker. -

Choral Music

of quality of experience of exciting locations of great adjudicators of exceptional service of North American Music Festivals 2001 Season, our 17th year: New York City· Myrtle Beach • Toronto* • Virginia Beach I www.greatfestivals.com I toll-free: 1-800-533-6263 Now registering concert choirs, show choirs, women's choirs, madrigal choirs, chamber Ithoirs, men's choirs, and ja_zz choirs for adjudications with mini-clinics Custom Tours also available *Disney's The Lion King Musical now open in Toronto. Call for details! Official Publication of the American Choral Directors Association Volume Forty-One Number Five DECEMBER 2000 CHORALjO Carroll Gonzo Ann Easterling EDITOR MANAGING EDITOR COLUMNS ARTICLES From the Executive Director ......... 2 A Guide to a Historically From the President ....................... 3 Accurate Performance of From the Editor ............................ 4 Edvard Grieg's Fire Salmer Letters to the Editor ...................... 4 [Four Psalms], op. 74 ............ 9 by Mary Buch The Power of Choral Singing ...... 43 A Speech by Garrison Keillor Candidate Information ............... 65 Selected Examples of Student Times ............................ 69 Scorr Dorsey, editor Choreinbau in the Cantatas On the Voice .............................. 75 of]. S. Bach ........................ 25 Sharon Hansen, editor by Pat Flannagan Compact Disc Reviews ............... 81 Richard J. Bloesch, editor Book Reviews ............................. 85 An Interview with Stephen Town, editor Robert Porco ...................... 37 Choral Reviews ........................... 91 Richard Nance, editor by Jonathan Talberg Repertoire and Standards Committee Reports .................... 71 LITERATURE FORUM 1999-2000 All-State Choirs: Choral Literature San Antonio Spotlight .............. 102 and Conductors ............................................................ 47 Advertisers Index ...................... 104 by Rebecca R. Reames SP E C IAL Cover: an image of Edvard Grieg. Design by Efrain Guerrero, Ausrin, Texas. -

Cscd515gloriabooklet-4

The other pieces are all anthems, primarily intended for use in the context GLORIA of a church service. They range in difficulty from very simple to fairly The Sacred Music of John Rutter challenging, though it was my hope in writing them that none would be beyond the reach of a capable church choir. Although the accompaniments were originally for organ (or, in the case of For the beauty of the earth and All he music heard on this recording represents a cross-section of the sacred things bright and beautiful, for piano), I enjoyed scoring them for orchestra Tchoral pieces I have written over a period of some thirty years, from the and prefer them in this form. The unaccompanied pieces, however, (Cantate 1970s to 2004. Two paramount considerations shaped it: first, the performers Domino, God be in my head, Open thou mine eyes, and A prayer of Saint Patrick) and occasions it was written for, and second the texts, which I always choose reflect my love of the a cappella medium. Wedding Canticle is exceptional in with great deliberation. that I wrote it with flute and guitar accompaniment. Gloria, the most substantial piece, was written as a concert work. It was Some of the texts are familiar and have been set to music many times—what commissioned by the Voices of Mel Olson, Omaha, Nebraska, and I directed composer, after all, could resist God be in my head or Psalm 150?—but it was a the first performance on the occasion of a visit to the United States—the first particular pleasure to happen upon such lovely texts as Open thou mine eyes or of many—in May 1974. -

San Francisco Lyric Chorus from British Shores . . . Christmas Across

From British Shores . Christmas Across the Pond A Gift Basket of Less Familiar Choral Works San Francisco Lyric Chorus Robert Gurney, Music Director Jonathan Dimmock, Organ & Piano Saturday, December 7 & Sunday, December 8, 2013 St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, San Francisco, California San Francisco Lyric Chorus Robert Gurney, Music Director Board of Directors Jim Bishop, Director Helene Whitson, President Nora Klebow, Director Karen Stella, Secretary Kristen Schultz Oliver, Director Bill Whitson, Treasurer Julia Bergman, Director Welcome to the Fall 2013 Concert of the San Francisco Lyric Chorus. Since its formation in 1995, the Chorus has offered diverse and innovative music to the community through a gathering of singers who believe in a commonality of spirit and sharing. The début concert featured music by Gabriel Fauré and Louis Vierne. The Chorus has been involved in several premieres, including Bay Area composer Brad Osness’ Lamentations, Ohio composer Robert Witt’s Four Motets to the Blessed Virgin Mary (West Coast premiere), New York composer William Hawley’s The Snow That Never Drifts (San Francisco premiere), San Francisco composer Kirke Mechem’s Christmas the Morn, Blessed Are They, To Music (San Francisco premieres), and selections from his operas, John Brown and The Newport Rivals, our 10th Anniversary Commission work, the World Premiere of Illinois composer Lee R. Kesselman’s This Grand Show Is Eternal, Robert Train Adams’ It Will Be Summer—Eventually and Music Expresses (West Coast premieres), as well as the Fall 2009 World Premiere of Dr. Adams’ Christmas Fantasy. And now, join us as we explore wonderful holiday music from our British neighbors across the pond! Please sign our mailing list, located in the foyer.