Food Photography and Still Life Paintings: a Single Subject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Be Creative with Light. and with System

BE CREATIVE WITH LIGHT. AND WITH SYSTEM. PREFACE 3 DEAR READER The challenge of thoroughly ad- our engineers as they push the it leaves nothing to be desired in dressing your needs and repeatedly technology to its limits with a living terms of operating convenience, surprising you with innovations is suite of broncolor innovations that longevity, value for money, and reli- what motivates us. And light is our become the global benchmark. ability. The objective stands. passion. Essentially, we have much Beyond the spirit of innovation, At www.broncolor.com, you can find in common. You face daily chal- nothing has changed as regards detailed information on the entire lenges, too. Every new assignment the legendary quality and depend- broncolor product line. calls for different, refined, and sur- ability that you have come to expect You’re the judge. Let the following prising photographic solutions. of broncolor products in your every- pages acquaint you with the current That’s where we want to offer our day work. Every device that leaves broncolor product line. We look support. We tap every single per- our production facility has under- forward to the continued privilege sonal contact with your colleagues gone exhaustive functionality tests. of serving you – for many years to from all over the world and ask Where possible, innovations are come. them how we can provide assis- compatible with previous-generation tance in the form of solutions that products. Over the years, this will ultimately benefit the entire systematically implemented philo- community in the studio and on lo- sophy has enriched the broncolor cation. -

Sony Introduces High-Resolution Alpha 7R IV Camera

Press Release Sony Introduces High-Resolution Alpha 7R IV Camera with World’s First 61.0 MP Back-illuminated Full-frame Image Sensor Unprecedented highest resolution and widest dynamic range for αTM (AlphaTM) system combined with high speed performance, in a lightweight compact body • World’s firsti 35mm full-frame 61.0 MPii back-illuminated Exmor R™ CMOS image sensor with latest-generation BIONZ X™ image processor • 15-stopiii dynamic range at low sensitivities, resulting in smooth natural gradations ranging from deep shadows to highlights • High-speed continuous shooting at up to 10 fpsiv with full AF / AE tracking for approx. 7 secondsv in full-frame mode with an increased buffer memory, and approximately three times more in APS-C mode • 567 focal-plane phase-detection AF points covering 74% of image area and 425 contrast AF points • Debut of Real-time Eye AF for movie recordingvi and advanced Real-time Trackingvii plus Real-time Eye AF for still image recording • Features an APS-C crop mode delivering stunning high resolution of 26.2MP2 • 5.76 million dot UXGA (Ultra-XGA) OLED Tru-Finder™ electric viewfinder with outstanding detail, brightness and contrast • Upgraded connectivity and operability including high-speed Wi-Fi support, wireless PC remote connectivityviii, FTP wireless transfer, faster data transfer via USB and more • Professional 4K movie recording functionality including full pixel readout with no pixel binning in Super 35mm modeix, S-Log3, HDR workflow support • Multi Interface Shoe™ with digital audio interface deliver the high-quality sound recording with new Sony’s microphones and XLR adaptor • Additional enhancements to the body design include an improved grip and button for improvised control with compact, lightweight body Hong Kong, August 15, 2019 – Sony today announced the latest addition to its acclaimed Alpha™ 7R series full-frame mirrorless camera line-up; the extremely versatile, powerful Alpha 7R IV (ILCE-7RM4). -

Build Interest in Prehistoric Site Through Still Life, Landscape, and Story Photography Artworks

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 12, DECEMBER 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Build Interest in Prehistoric Site Through Still Life, Landscape, and Story Photography Artworks Winny Gunarti Widya Wardani, Wulandari, Syahid Abstract: The existence of prehistoric sites in Indonesia is important to preserved because it is a cultural heritage. If there is less interest in relics of artifacts, then it has the potential to erase prehistoric traces in the minds of the younger generation. There are many ways to build interest in prehistoric sites, including through photographic art. This study examines the visuals strength in the still life, landscape, and story photography genres which can influence people's interest in prehistoric sites. Quantitatively, a survey of tourists at the Gunung Padang Site, Cianjur, West Java shows 88 percent think historical places need to be visualized through pictures or photos that attract knowledge. Meanwhile, qualitatively, this study shows the strength of elements in the still life, landscape and story photography genres which are able to build certain visual perceptions in the minds of the readers. In digital photography technique, the processing of visual signs is mainly influenced by the power of shooting for impact, which consists of distance and perspective, and focus of attention as a process of reading visual signs using a visual communication design approach. This study is expected to become an academic reference in the field of alternative media to build interest in prehistoric sites. Keywords: Prehistoric site, still life, landscape, story, photography artworks. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION TH E Gunung Padang Site in Karyamukti Village, Cianjur, West particularly in the application of photographic art as an Java is a tourist location as well as a research center for alternative medium to build younger generations' interest in megalithic sites. -

Downloading of Results Through Search Logs from a Commercial Image Provider

This publication is made freely available under ______ __ open access. AUTHOR(S): TITLE: YEAR: Publisher citation: OpenAIR citation: Publisher copyright statement: This is the ______________________ version of an article originally published by ____________________________ in __________________________________________________________________________________________ (ISSN _________; eISSN __________). OpenAIR takedown statement: Section 6 of the “Repository policy for OpenAIR @ RGU” (available from http://www.rgu.ac.uk/staff-and-current- students/library/library-policies/repository-policies) provides guidance on the criteria under which RGU will consider withdrawing material from OpenAIR. If you believe that this item is subject to any of these criteria, or for any other reason should not be held on OpenAIR, then please contact [email protected] with the details of the item and the nature of your complaint. This publication is distributed under a CC ____________ license. ____________________________________________________ ANALYSING CREATIVE IMAGE SEARCH INFORMATION NEEDS Elena Konkova1, Andrew MacFarlane1 and Ayse Goker2 1Department of Computer Science, City University London, London EC1V 0HB 2School of Computing Science and Digital Media, Robert Gordon University, Garthdee Road, Aberdeen, AB10 7QB ABSTRACT Creative professionals in advertising, marketing, design and journalism search for images to visually represent a concept for their project. The main purpose of this paper is to present an analysis of documents known as briefs to find search facets, which are widely used in creative industries as a requirements document to describe an information need. The briefs specify the type of image required, such as the content and context of use for the image, and represent the topic from which the searcher builds an image query. -

Developing a Still Life Paintings Art Collection

CoLLeCting ReSource guiDe Developing a Still Life Paintings Art Collection Laura Robb, Blue Cup with Crabapples, oil, 10 x 16. Discovering the prescient power and timeless appeal of still life art. A Quiet Dynamic David Riedel’s still-life paintings reveal a subtle sense of movement, mystery, and depth By g ussie F AuntLeRoy da vi D R ie D e L As the pAle light fades into dusk through north-facing skylights in his Portland, OR, studio, painter David Riedel sits quietly, watching a painting on his easel. His hands are in his lap. His tools at this moment are his eyes, closely observing how changes happen in the painting’s areas of light and dark— seeing how shadows and highlights fall on a brown clay jug surrounded by au- tumn leaves. What he’s hoping to see is the painting’s sense of mystery and depth increase in proportion to the studio’s disappearing light. “It may be a quiet still life, but it’s very dynamic,” the artist points out, his eyes still on the easel. “It’s not a station- ary thing at all. You have to be passion- ate about some idea, and then build in the tensions and energy and flow. There should be a lot going on. And the fascina- tion for me is: How well can I see what’s truly there?” As it turns out, since moving from northern New Mexico to Portland a few years ago, Riedel has had to work harder to see subtle variations in color and other nuances as he paints. -

TESSERACT -- Antique Scientific Instruments

TESSERACT Early Scientific Instruments Special Issue: OPTICAL PLEASURES Catalogue One Hundred Seven Summer, 2018 $10 CATALOGUE ONE HUNDRED SEVEN Copyright 2018 David Coffeen CONDITIONS OF SALE All items in this catalogue are available at the time of printing. We do not charge for shipping and insurance to anywhere in the contiguous 48 states. New York residents must pay applicable sales taxes. For buyers outside the 48 states, we will provide packing and delivery to the post office or shipper but you must pay the actual shipping charges. Items may be reserved by telephone, and will be held for a reasonable time pending receipt of payment. All items are offered with a 10-day money-back guarantee for any reason, but you pay return postage and insurance. We will do everything possible to expedite your shipment, and can work within the framework of institutional requirements. The prices in this catalogue are net and are in effect through December, 2018. Payments by check, bank transfer, or credit card (Visa, Mastercard, American Express) are all welcome. — David Coffeen, Ph.D. — Yola Coffeen, Ph.D. Members: Scientific Instrument Society American Association for the History of Medicine Historical Medical Equipment Society Antiquarian Horological Society International Society of Antique Scale Collectors Surveyors Historical Society Early American Industries Association The Oughtred Society American Astronomical Society International Coronelli Society American Association of Museums Co-Published : RITTENHOUSE: The Journal of the American Scientific Instrument Enterprise (http://www.etesseract.com/RHjournal/) We are always interested in buying single items or collections. In addition to buying and selling early instruments, we can perform formal appraisals of your single instruments or whole collections, whether to determine fair market value for donation, for insurance, for loss, etc. -

17-217-Stilllife-Booklet.Pdf

themes (flower and fruit still lifes), to modern interpretations of the vanitas symbols (constructions with objects that refer to our everyday surroundings) to nearly abstract, three-dimensional still lifes in the exhibition space. Photography in the Netherlands has In 2011 Foam is celebrating its tenth had a tradition of experimenting with anniversary. The museum first opened staged photography since the 1970s. its doors in 2001 with the Dutch Delight The still life has also been a major theme exhibition, taking ‘Dutch Light’ as its in this tradition. Exaggeration and central subject. It was a typically Dutch enlargement are devices which originat- historical art theme, for which Dutch ed from advertising and much of the painting is famous the world over. Now, staged photography of that time was Still/ in Still/Life – Contemporary Dutch inspired by conceptual as well as adver- Photography, Foam has put together tising photography. an exhibition comprised of work by Many of the photographers in this Dutch photographers giving surprising exhibition also work at this juncture. interpretations of another classic They move easily between established subject in Dutch art history: the still life. art institutions, the editorial world of The still life could be considered magazines and publications, and the a composition of lifeless, impassive commercial advertising sphere. A clear, Life objects. Although the Romans painted recognisable style can be seen in both the first still lifes, the genre mainly their personal and their commercial became known through 17th-century work, such as that of so-called ‘Dutch Dutch and Flemish paintings. These Design’ which alludes to a typically paintings can often be categorised by Dutch design aesthetic: minimalist, Contemporary subject: still lifes with flowers, still lifes experimental, innovative, unconventional of food on richly laid-out tables and and with humour. -

IMAGINE... the POWER of a PHOTOGRAPH WINTER/SPRING 2021 CONTENTS General Information Mission Statement

Serving the Photo Community Since 1999 Now offering classes online! IMAGINE... THE POWER OF A PHOTOGRAPH WINTER/SPRING 2021 CONTENTS General Information Mission Statement ......................................................................................... 2 Letter from Julia Dean, Executive Director .......................................... 2 The Board of Directors, Officers and Advisors ........................................... 3 Charter Members, Circle Donors and Donors ................................... 3 Donate ................................................................................................................. 4 Early Bird Become a Member ........................................................................................ 5 Certificate Programs ..................................................................................... 6 One-Year Professional Program ............................................................... 7 Gets the Online Learning Calendar .......................................................................8-9 Webinar Calendar .........................................................................................10 In-Person Learning Calendar ..................................................................11 Discount Mentorship Program ...................................................................................12 Register early for great discounts on The Master Series ........................................................................................13 Youth Program .................................................................................24-25, -

COMPOSED Still LIFE Protograplty

COMPOSED STill LIFE PROTOGRAPlty I ~ / © Central University of Technology, Free State HCVERWOERD COMPOSED STILL LIFE PHOTOGRAPHY NOVEMBER 1992 © Central University of Technology, Free State COMPOSED STILL LIFE PHOTOGRAPHY BY HENDRIKA CHRISTINA VERWOERD SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL COMPLIANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE NATIONAL DIPLOMA IN THE DEPARTMENT ART AND DESIGN, OFS TECHNIKON NOVEMBER 1992 © Central University of Technology, Free State CONTENT 1. Introduction 1 - 2 2 • Early Beginnings of still life photography 3 - 5 3 . Compositional devices 8 3.1 Visual elements 8 - 13 3.2 Elements of design 13 - 14 4 . Specialized Fields 15 4.1 Beverage Photography 15 - 16 4 . 2 Food Photography 19 4.3 Jewelry Photography 22 5. Present Trends 24 -27 6. Author's Work 29 - 30 7 . Conclusion 49 8 . Bibliography 50 © Central University of Technology, Free State LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig 1 Roger Fenton. "still life with statue" 1860 6 Taken from: Weaver 1989, plate 109 Fig 2 Fox Talbot . "Articles of China" 1844 7 Taken from : Weaver 1989, plate 3 Fig 3 seith Joel . Beverage - Product Shot 17 Taken from: Joel 1990, p 41 Fig 4 Seith Joel . Beverage - Lifestyle shot 18 Taken from : Joel 1990, p 43 Fig 5 seith Joel . Food - Editorial 20 Taken from : Joel 1990, p 49 Fig 6 seith Joel . Food - Advertising 21 Taken from: Joel 1990, p 59 Fig 7 seith Joel . Jewelry 23 Taken from: Joel 1990, p 85 Fig 8 Nora Scarlett. A closet and a dress 2 6 Taken from: O'Connor 1989, p 66 Fig 9 Marc David Cohen. Gravity 28 Taken from: O'Connor 1989, p 90 © Central University of -

Impressionist Still Life 2001

Impressionist Still Life 2001- 2002 Finding Aid The Phillips Collection Library and Archives 1600 21st Street NW Washington D.C. 20009 www.phillipscollection.org CURATORIAL RECORDS IN THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION ARCHIVES INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION Collection Title: Impressionist Still Life; exhibition records Author/Creator: The Phillips Collection Curatorial Department. Eliza E. Rathbone, Chief Curator Size: 8 linear feet; 19 document boxes Bulk Dates: 1950-2001 Inclusive Dates: 1888-2002 (portions are photocopies) Repository: The Phillips Collection Archives INFORMATION FOR USERS OF THE COLLECTION Restrictions: The collection contains restricted materials. Please contact Karen Schneider, Librarian, with any questions regarding access. Handling Requirements: Preferred Citation: The Phillips Collection Archives, Washington, D.C. Publication and Reproduction Rights: See Karen Schneider, Librarian, for further information and to obtain required forms. ABSTRACT Impressionist Still Life (2001 - 2002) exhibition records contain materials created and collected by the Curatorial Department, The Phillips Collection, during the course of organizing the exhibition. Included are research, catalogue, and exhibition planning files. HISTORICAL NOTE In May 1992, the Trustees of The Phillips Collection named noted curator and art historian Charles S. Moffett to the directorship of the museum. Moffett, a specialist in the field of painting of late-nineteenth-century France, was directly involved with the presentation of a series of exhibitions during his tenure as director (1992-98). Impressionist Still Life (2001-2002) became the third in an extraordinary series of Impressionist exhibitions organized by Moffett at The Phillips Collection, originating with Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir‟s Luncheon of the Boating Party in 1996, followed by the nationally touring Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige, on view at the Phillips in 1998. -

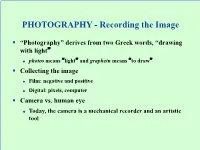

Photography PART 2 MEDIA and PROCESSES PHOTOGRAPHY - Recording the Image

Chapter 2.5 Photography PART 2 MEDIA AND PROCESSES PHOTOGRAPHY - Recording the Image . “Photography” derives from two Greek words, “drawing with light” photos means “light” and graphein means “to draw” . Collecting the image Film: negative and positive Digital: pixels, computer . Camera vs. human eye Today, the camera is a mechanical recorder and an artistic tool Gateways to Art: Understanding the Visual Arts, Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, M. Kathryn Shields Chapter 2.5 Photography PART 2 MEDIA AND PROCESSES The History of Photography . Camera obscura Projection of outside scene First drawn, then captured on light-sensitive material Room-sized then portable (eighteenth-century) camera obscura . Negative/positive processes Cyanotype-blue line on white background Calotype-a negative image is turned into a positive one using sunlight circa 1841 Daguerreotype . Digital Processes Pixels, digital files, display, manipulation Gateways to Art: Understanding the Visual Arts, Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, M. Kathryn Shields Rainer Gemma-Frisius, first published illustration of a camera obscura, 1544. William Henry Fox Talbot, The Oriel Window, South Gallery, Lacock Abbey, 1835 or 1839. Photogenic drawing negative, 3¼ x 4¼”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Chapter 2.5 Photography PART 2 MEDIA AND PROCESSES Portrait Photography . One of photography’s popular uses Substitute for more costly painted portraits People could eventually take their own pictures Gateways to Art: Understanding the Visual Arts, Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, M. Kathryn Shields Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt, 1865. Albumen print, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France Chapter 2.5 Photography PART 2 MEDIA AND PROCESSES Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt . Sarah Bernhardt was a famous actress this would have been “in vogue and cutting edge” in her time .