The Yorkshire Miners and the 1893 Lockout: the Featherstone "Massacre"*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 29, 2010 2011 ANNUAL COMMUNTIY CAMPAIGN $100,000 Matching Grant for New Or Increased Gifts! GENEROUS Challenge

$100,000 MATCHING GRANT FOR ALL NEW GIFTS AND GIFT INCREASES FOR THE 2011 ANNUAL COMMUNITY CAMPAIGN! Ta k e t h e challenge, double your impactl See below for m ore info .. MASSACHUSETTS 21 Heshvan 5771 Vol. XII - Issue XXI WWW.JVHRI.ORG October 29, 2010 2011 ANNUAL COMMUNTIY CAMPAIGN $100,000 matching grant for new or increased gifts! GENEROUS challenge. Before you write your GROUP of com check or go online to enter your munity philanthro- credit card information, please ists has established know: This year, your campaign a Sl00,000 challenge grant: For gift will have extra impact. So, every new gift or gift increase to won't you please add a few extra the Jewish Federation of Rhode dollars to your pledge this year? Island 's 2011 Annual Commu Donate at wwwjFRI.org or nity Campaign, they will match call M ichele Gallagher at 421- it up to Sl00,000. 4111, ext. 165. Add extra impact - take the /Alisa Grace Photography From far left. Richard Licht. Herb Stern and Gary Licht line up for the book signing with Gregory Levey. author of How to Make Peasce in the Middle East in Six Months or less Without leaving Your Apartment. and the keynote speaker. At Temple Beth-El, JFRl's Main Event ..-- launches Annual Community Campaign nity Campaign and a JFRI vice Thanks to dollars raised here Peace in the Middle president. "I have a wonderful vol in greater Rhode Island, Jews in East? Read Gregory unteer job - asking for resources Rhode Island, throughout the Diaspora and in Israel are living Levey's book NEWS ANALYSIS safer, happier and more Jewishly to learn more from Jews to help other Jews in engaged lives. -

Towards a Model of Child Protection

Families, Relationships and Societies • vol x • no x • xx–xx • © Policy Press 2016 • #FRS Print ISSN 2046 7435 • Online ISSN 2046 7443 • http://dx.doi.org/10.1332/204674316X14552878034622 article Let’s stop feeding the risk monster: Towards a social model of ‘child protection’ Brid Featherstone,1 [email protected] University of Huddersfield, UK Anna Gupta, [email protected] Royal Holloway University of London, UK Kate Morris, [email protected] University of Sheffield, UK Joanne Warner, [email protected] University of Kent, UK This article explores how the child protection system currently operates in England. It analyses how policy and practice has developed, and articulates the need for an alternative approach. It draws from the social model as applied in the fields of disability and mental health, to begin to sketch out more hopeful and progressive possibilities for children, families and communities. The social model specifically draws attention to the economic, environmental and cultural barriers faced by people with differing levels of (dis)ability, but has not been used to think about ‘child protection’, an area of work in England that is dominated by a focus on risk and risk aversion. This area has paid limited attention to the barriers to ensuring children and young people are cared for safely within families and communities, and the social determinants of much of the harms they experience have not been recognised because of the focus on individualised risk factors. key words child protection • risk • parenting • social model Introduction In this article we argue that it is time to question a child protection project that colludes with a view that the greatest threats to children’s safety and wellbeing are posed by their parents or carers’ intentional negligence or abuse. -

May 2021 FOI 2387-21 Drink Spiking

Our ref: 2387/21 Figures for incidents of drink spiking in your region over the last 5 years (year by year) I would appreciate it if the figures can be broken down to the nearest city/town. Can you also tell me the number of prosecutions there have been for the above offences and how many of those resulted in a conviction? Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police receive reports of crimes that have occurred following a victim having their drink spiked, crimes such as rape, sexual assault, violence with or without injury and theft. West Yorkshire Police take all offences seriously and will ensure that all reports are investigated. Specifically for victims of rape and serious sexual offences, depending on when the offence occurred, they would be offered an examination at our Sexual Assault Referral Centre, where forensic samples, including a blood sample for toxicology can be taken, with the victim’s consent, if within the timeframes and guidance from the Faculty for Forensic and Legal Medicine. West Yorkshire Police work with support agencies to ensure that all victims of crime are offered support through the criminal justice process, including specialist support such as from Independent Sexual Violence Advisors. Recorded crime relating to spiked drinks, 01/01/2016 to 31/12/2020 Notes Data represents the number of crimes recorded during the period which: - were not subsequently cancelled - contain the search term %DR_NK%SPIK% or %SPIK%DR_NK% within the crime notes, crime summary and/or MO - specifically related to a drug/poison/other noxious substance having been placed in a drink No restrictions were placed on the type of drink, the type of drug/poison or the motivation behind the act (i.e. -

Wakefield, West Riding: the Economy of a Yorkshire Manor

WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR By BRUCE A. PAVEY Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1991 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1993 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR Thesis Approved: ~ ThesiSAd er £~ A J?t~ -Dean of the Graduate College ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply indebted to to the faculty and staff of the Department of History, and especially the members of my advisory committee for the generous sharing of their time and knowledge during my stay at O.S.U. I must thank Dr. Alain Saint-Saens for his generous encouragement and advice concerning not only graduate work but the historian's profession in general; also Dr. Joseph Byrnes for so kindly serving on my committee at such short notice. To Dr. Ron Petrin I extend my heartfelt appreciation for his unflagging concern for my academic progress; our relationship has been especially rewarding on both an academic and personal level. In particular I would like to thank my friend and mentor, Dr. Paul Bischoff who has guided my explorations of the medieval world and its denizens. His dogged--and occasionally successful--efforts to develop my skills are directly responsible for whatever small progress I may have made as an historian. To my friends and fellow teaching assistants I extend warmest thanks for making the past two years so enjoyable. For the many hours of comradeship and mutual sympathy over the trials and tribulations of life as a teaching assistant I thank Wendy Gunderson, Sandy Unruh, Deidre Myers, Russ Overton, Peter Kraemer, and Kelly McDaniels. -

Collections Guide 9 Tithe

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 9 TITHE Contacting Us What were tithes? Please contact us to book a Tithes were a local tax on agricultural produce. This tax was originally paid place before visiting our by farmers to support the local church and clergy. When Henry VIII searchrooms. abolished the monasteries in the 16th century, many Church tithe rights were sold into private hands. Owners of tithe rights on land which had WYAS Bradford previously belonged to the Church were known as ‘Lay Impropriators’. Margaret McMillan Tower Tithe charges were extinguished in 1936. Prince’s Way Bradford What is a tithe map? BD1 1NN Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0152 Disputes over the assessment and collection of tithes were resolved by the e. [email protected] Tithe Commutation Act of 1836. This allowed tithes in kind (wheat, hay, wool, piglets, milk etc.) to be changed into a fixed money payment called a WYAS Calderdale ‘tithe rent charge’. Detailed maps were drawn up showing the boundaries Central Library & Archives of individual fields, woods, roads, streams and rivers, and the position of Square Road buildings. Most tithe maps were completed in the 1840s. Halifax HX1 1QG What is a tithe apportionment? Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0151 e. [email protected] The details of rent charges payable for each property or field were written WYAS Kirklees up in schedules called ‘tithe apportionments’ . This part of the tithe award Central Library recorded who owned and occupied each plot, field names, the use to which Princess Alexandra Walk the land was being put at the time, plus a calculation of its value. -

Popular Political Oratory and Itinerant Lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the Age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa M

Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa Martin This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of York Department of History January 2010 ABSTRACT Itinerant lecturers declaiming upon free trade, Chartism, temperance, or anti- slavery could be heard in market places and halls across the country during the years 1837- 60. The power of the spoken word was such that all major pressure groups employed lecturers and sent them on extensive tours. Print historians tend to overplay the importance of newspapers and tracts in disseminating political ideas and forming public opinion. This thesis demonstrates the importance of older, traditional forms of communication. Inert printed pages were no match for charismatic oratory. Combining personal magnetism, drama and immediacy, the itinerant lecturer was the most effective medium through which to reach those with limited access to books, newspapers or national political culture. Orators crucially united their dispersed audiences in national struggles for reform, fomenting discussion and coalescing political opinion, while railways, the telegraph and expanding press reportage allowed speakers and their arguments to circulate rapidly. Understanding of political oratory and public meetings has been skewed by over- emphasis upon the hustings and high-profile politicians. This has generated two misconceptions: that political meetings were generally rowdy and that a golden age of political oratory was secured only through Gladstone’s legendary stumping tours. However, this thesis argues that, far from being disorderly, public meetings were carefully regulated and controlled offering disenfranchised males a genuine democratic space for political discussion. -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

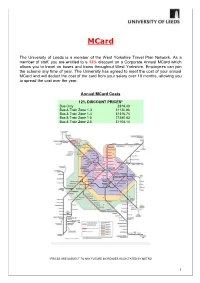

Mcard Application

MCard The University of Leeds is a member of the West Yorkshire Travel Plan Network. As a member of staff, you are entitled to a 12% discount on a Corporate Annual MCard which allows you to travel on buses and trains throughout West Yorkshire. Employees can join the scheme any time of year. The University has agreed to meet the cost of your annual MCard and will deduct the cost of the card from your salary over 10 months, allowing you to spread the cost over the year. Annual MCard Costs 12% DISCOUNT PRICES * Bus Only £818.40 Bus & Train Zone 1-3 £1120.86 Bus & Train Zone 1-4 £ 1316.74 Bus & Train Zone 1-5 £ 1580.83 Bus & Train Zone 2-5 £1104.14 *PRICES ARE SUBJECT TO ANY FUTURE INCREASES AS DICTATED BY METRO 1 As a first step, you will need to order your Corporate Annual MCard on the MCard website www.m-card.co.uk. Please also complete the attached deduction application and return a hard copy to the Staff Benefits Team, 11.11 E.C. Stoner Building. Please retain a copy of the Terms and Conditions. Corporate Annual MCard Terms and Conditions The purpose of this Scheme is to provide discounted payment terms for staff. The University is not involved, nor liable, for the delivery of WYCA services. Staff have a separate contract with WYCA for delivery of their services. WYCA’s terms relating to the use of their MCard are available at https://m-card.co.uk/terms-of-use/annual-mcard-terms- conditions/ A Bus-Only MCard is valid on virtually all the services of all bus operators within West Yorkshire. -

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TECHNICAL REPORTS Onshore Geology Series TECHNICAL REPORT Waf97158 OBSERVATIONS of COAL CLEAT in BRITI

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TECHNICAL REPORTS Onshore Geology Series TECHNICAL REPORT WAf97158 OBSERVATIONS OF COAL CLEAT IN BRITISH COALFIELDS R A Ellison Geographical index UK, Yorkshire, Lancashire, Warwickshire, Nottinghamshire Subject Index Coal, fractures, joints, cleat Bibliographic reference Ellison, R A. 1997. Observations of coal cleat in British coalfields. British Geological Survey Technical Report WAf97158 (Keyworth: British Geological Survey.) 0NERC copyright 1997 Keyworth, British Geological Survey 1997 \ British Geological Survey Technical Report WA/97/58 Contents Introduction Cleat and Joint Measurements Locality details Acknowledgements References Index of localities and units with joints andor coal cleat azimuths recorded P British Geological Survey Technical Report WA/97/58 List of Figures Figure 1 Skelton Opencast Site Figure 2 Lawns Lane and Lofthouse Opencast sites Figure 3 St John’s, Ackton and Cornwall Opencast sites and Sharlston and Prince of Wales collieries Figure 4 Detail at Ackton Opencast site Figure 5 Comparison of cleat in the Stanley Main coal at Sharlston and Prince of Wales collieries Figure 6 Tinsley Park, Waverley East and Pithouse Opencast sites Figure 7 Slayley and Dixon Opencast sites and Duckmanton Railway Cutting Figure 8 Ryefield and Godkin Opencast sites Figure 9 Cossall Opencast site Figure 10 Sudeley Opencast site Figure 11 Chapeltown Opencast site Figure 12 Riccall Colliery Figure 13 Askern Colliery Figure 14 The Lancaster Fells and Ingleton Coalfield Figure 15 Meltonfield Coal fiom Tinsley Park Opencast site showing two orthogonal well developed cleat sets Figure 16 Two Foot Coal fiom Tinsley Park Opencast site showing one main cleat and a minor, orthogonal, back cleat Figure 17 Deep Coal fiom the Ingleton Coalfield showing two conjugate cleat sets Figure 18 Dixon Opencast site: well developed cleat in the Mickley Thick Coal immediately overlying the Mickley Cannel Coal which has no cleat but joints at an acute angle to the cleat. -

Divisonal Secretaries Teams Report

Divisonal Secretarys Team Report for U09 Divisional Secrectary Stephen/ Russell Walters/mell Email :- [email protected] Phone :- (07939) 836310 Mobile :- (07488) 296005 Team ID Number Name Ground Games played at Home Colours Shirt-Shorts-Socks Division Squad 753 Amaranth Juniors F.C. Amaranth Football Club Manston Lane Crossgates Leeds LS15 8AD Purple / White Trim - Purple / White Trim - Purple / White Trim 1 Team Squad Contact :- Manager Mark Harrison Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07830) 522642 588 Beeston Juniors F.C. New Bewerleys School Bismarck Drive Beeston Leeds LS11 6TB Royal Blue / White Stripes - Royal Blue - Royal Blue 2 Teams Squad Contact :- Manager Russell Mellor Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07939) 836310 736 Chapeltown Juniors F.C. (Orange) Prince Philip Centre Scott Hall Avenue Leeds LS7 2HJ Orange - Black - Black 1 Team Squad Contact :- Manager William Bowler Email :- [email protected] Phone :- ( 0113) 2623233 Mobile :- (07392) 552587 618 Churwell Lions Junior F.C. (Blacks) Nepshaw Lane Off Asquith Avenue Morley Leeds LS27 9QQ Blue / Black Stripes - Black - Black 2 Teams Squad Contact :- Manager Ian Sweeney Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07725) 586617 955 Churwell Lions Junior F.C. (Blues) Nepshaw Lane Off Asquith Avenue Morley Leeds LS27 9QQ Blue / Black Stripes - Black - Black 1 Team Squad Contact :- Manager James Lorenz-Duval Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07843) 249111 592 Colton Juniors F.C. (Green) Colton Sports & Institute School Lane Colton Leeds LS15 9AL Yellow - Green - Green 2 Teams Squad Contact :- Manager Jim Boughton Email :- [email protected] Phone :- ( 0113) 2326342 Mobile :- (07793) 726665 741 Colton Juniors F.C. -

Drink and the Victorians

DRINK AND THE VICTORIANS A HISTORY OF THE BRITISH TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT PAGING NOTE: Pamphlets, journals, and periodicals are paged using the number of the item on the list below, and the call number 71-03051. Books are cataloged individually – get author/title info below, and search SearchWorks for online record and call number. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE This collection has been formed by the amalgamation of two smaller but important collections. The larger part, probably about three-quarters of the whole, was formed by William Hoyle of Claremont, Bury, near Manchester. The other part was formerly in the Joseph Livesey Library, Sheffield, and many of the pamphlets carry that library stamp. The catalogue has three main elements: pamphlets and tracts; books, including a section of contemporary biography; and newspapers, journals and conference reports. There are around 1400 separately published pamphlets and tracts but a series of tracts, or part of a series, has usually been catalogued as one item. The Hoyle collection of pamphlets, is bound in 24 volumes, mostly half black roan, many with his ownership stamp. All the pieces from the Joseph Livesey Library are disbound; so that any item described as "disbound" may be assumed to be from the Livesey collection and all the others, for which a volume and item number are given, from Hoyle's bound collection. INTRODUCTION By Brian Harrison Fellow and Tutor in Modern History and Politics, Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Anyone keen to understand the Victorians can hardly do better than devour Joseph Livesey's Staunch Teetotaler (458) or J.G. Shaw's Life of William Gregson. -

144 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

144 bus time schedule & line map 144 Castleford - Pontefract View In Website Mode The 144 bus line (Castleford - Pontefract) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Castleford <-> Featherstone: 5:45 PM (2) Castleford <-> Pontefract: 7:50 AM - 4:55 PM (3) Featherstone <-> Castleford: 7:18 AM (4) Featherstone <-> Pontefract: 7:26 AM (5) Pontefract <-> Ackton: 5:25 PM (6) Pontefract <-> Castleford: 8:10 AM - 4:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 144 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 144 bus arriving. Direction: Castleford <-> Featherstone 144 bus Time Schedule 34 stops Castleford <-> Featherstone Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:45 PM Bus Station Stand A, Castleford Albion Street, England Tuesday 5:45 PM Station Road, Castleford Wednesday 5:45 PM Jessop Street, Castleford Thursday 5:45 PM Lower Oxford St Beancroft Road, Castleford Friday 5:45 PM Beancroft Road Hugh St, Castleford Saturday 4:55 PM Beancroft Street Beancroft Rd, Castleford Beancroft Street Leaf St, Castleford 144 bus Info Falcon Drive Fulmar Rd, Castleford Direction: Castleford <-> Featherstone Stops: 34 Falcon Drive Gannett Close, Castleford Trip Duration: 31 min Falcon Drive, Castleford Line Summary: Bus Station Stand A, Castleford, Station Road, Castleford, Lower Oxford St Beancroft Falcon Dr Sheldrake Road, Castleford Road, Castleford, Beancroft Road Hugh St, Castleford, Beancroft Street Beancroft Rd, Barnes Road Quarry Court, Glasshoughton Castleford, Beancroft Street Leaf St, Castleford,