Towards a Model of Child Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2021 FOI 2387-21 Drink Spiking

Our ref: 2387/21 Figures for incidents of drink spiking in your region over the last 5 years (year by year) I would appreciate it if the figures can be broken down to the nearest city/town. Can you also tell me the number of prosecutions there have been for the above offences and how many of those resulted in a conviction? Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police receive reports of crimes that have occurred following a victim having their drink spiked, crimes such as rape, sexual assault, violence with or without injury and theft. West Yorkshire Police take all offences seriously and will ensure that all reports are investigated. Specifically for victims of rape and serious sexual offences, depending on when the offence occurred, they would be offered an examination at our Sexual Assault Referral Centre, where forensic samples, including a blood sample for toxicology can be taken, with the victim’s consent, if within the timeframes and guidance from the Faculty for Forensic and Legal Medicine. West Yorkshire Police work with support agencies to ensure that all victims of crime are offered support through the criminal justice process, including specialist support such as from Independent Sexual Violence Advisors. Recorded crime relating to spiked drinks, 01/01/2016 to 31/12/2020 Notes Data represents the number of crimes recorded during the period which: - were not subsequently cancelled - contain the search term %DR_NK%SPIK% or %SPIK%DR_NK% within the crime notes, crime summary and/or MO - specifically related to a drug/poison/other noxious substance having been placed in a drink No restrictions were placed on the type of drink, the type of drug/poison or the motivation behind the act (i.e. -

Collections Guide 9 Tithe

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 9 TITHE Contacting Us What were tithes? Please contact us to book a Tithes were a local tax on agricultural produce. This tax was originally paid place before visiting our by farmers to support the local church and clergy. When Henry VIII searchrooms. abolished the monasteries in the 16th century, many Church tithe rights were sold into private hands. Owners of tithe rights on land which had WYAS Bradford previously belonged to the Church were known as ‘Lay Impropriators’. Margaret McMillan Tower Tithe charges were extinguished in 1936. Prince’s Way Bradford What is a tithe map? BD1 1NN Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0152 Disputes over the assessment and collection of tithes were resolved by the e. [email protected] Tithe Commutation Act of 1836. This allowed tithes in kind (wheat, hay, wool, piglets, milk etc.) to be changed into a fixed money payment called a WYAS Calderdale ‘tithe rent charge’. Detailed maps were drawn up showing the boundaries Central Library & Archives of individual fields, woods, roads, streams and rivers, and the position of Square Road buildings. Most tithe maps were completed in the 1840s. Halifax HX1 1QG What is a tithe apportionment? Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0151 e. [email protected] The details of rent charges payable for each property or field were written WYAS Kirklees up in schedules called ‘tithe apportionments’ . This part of the tithe award Central Library recorded who owned and occupied each plot, field names, the use to which Princess Alexandra Walk the land was being put at the time, plus a calculation of its value. -

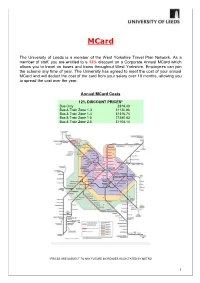

Mcard Application

MCard The University of Leeds is a member of the West Yorkshire Travel Plan Network. As a member of staff, you are entitled to a 12% discount on a Corporate Annual MCard which allows you to travel on buses and trains throughout West Yorkshire. Employees can join the scheme any time of year. The University has agreed to meet the cost of your annual MCard and will deduct the cost of the card from your salary over 10 months, allowing you to spread the cost over the year. Annual MCard Costs 12% DISCOUNT PRICES * Bus Only £818.40 Bus & Train Zone 1-3 £1120.86 Bus & Train Zone 1-4 £ 1316.74 Bus & Train Zone 1-5 £ 1580.83 Bus & Train Zone 2-5 £1104.14 *PRICES ARE SUBJECT TO ANY FUTURE INCREASES AS DICTATED BY METRO 1 As a first step, you will need to order your Corporate Annual MCard on the MCard website www.m-card.co.uk. Please also complete the attached deduction application and return a hard copy to the Staff Benefits Team, 11.11 E.C. Stoner Building. Please retain a copy of the Terms and Conditions. Corporate Annual MCard Terms and Conditions The purpose of this Scheme is to provide discounted payment terms for staff. The University is not involved, nor liable, for the delivery of WYCA services. Staff have a separate contract with WYCA for delivery of their services. WYCA’s terms relating to the use of their MCard are available at https://m-card.co.uk/terms-of-use/annual-mcard-terms- conditions/ A Bus-Only MCard is valid on virtually all the services of all bus operators within West Yorkshire. -

Divisonal Secretaries Teams Report

Divisonal Secretarys Team Report for U09 Divisional Secrectary Stephen/ Russell Walters/mell Email :- [email protected] Phone :- (07939) 836310 Mobile :- (07488) 296005 Team ID Number Name Ground Games played at Home Colours Shirt-Shorts-Socks Division Squad 753 Amaranth Juniors F.C. Amaranth Football Club Manston Lane Crossgates Leeds LS15 8AD Purple / White Trim - Purple / White Trim - Purple / White Trim 1 Team Squad Contact :- Manager Mark Harrison Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07830) 522642 588 Beeston Juniors F.C. New Bewerleys School Bismarck Drive Beeston Leeds LS11 6TB Royal Blue / White Stripes - Royal Blue - Royal Blue 2 Teams Squad Contact :- Manager Russell Mellor Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07939) 836310 736 Chapeltown Juniors F.C. (Orange) Prince Philip Centre Scott Hall Avenue Leeds LS7 2HJ Orange - Black - Black 1 Team Squad Contact :- Manager William Bowler Email :- [email protected] Phone :- ( 0113) 2623233 Mobile :- (07392) 552587 618 Churwell Lions Junior F.C. (Blacks) Nepshaw Lane Off Asquith Avenue Morley Leeds LS27 9QQ Blue / Black Stripes - Black - Black 2 Teams Squad Contact :- Manager Ian Sweeney Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07725) 586617 955 Churwell Lions Junior F.C. (Blues) Nepshaw Lane Off Asquith Avenue Morley Leeds LS27 9QQ Blue / Black Stripes - Black - Black 1 Team Squad Contact :- Manager James Lorenz-Duval Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07843) 249111 592 Colton Juniors F.C. (Green) Colton Sports & Institute School Lane Colton Leeds LS15 9AL Yellow - Green - Green 2 Teams Squad Contact :- Manager Jim Boughton Email :- [email protected] Phone :- ( 0113) 2326342 Mobile :- (07793) 726665 741 Colton Juniors F.C. -

Drink and the Victorians

DRINK AND THE VICTORIANS A HISTORY OF THE BRITISH TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT PAGING NOTE: Pamphlets, journals, and periodicals are paged using the number of the item on the list below, and the call number 71-03051. Books are cataloged individually – get author/title info below, and search SearchWorks for online record and call number. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE This collection has been formed by the amalgamation of two smaller but important collections. The larger part, probably about three-quarters of the whole, was formed by William Hoyle of Claremont, Bury, near Manchester. The other part was formerly in the Joseph Livesey Library, Sheffield, and many of the pamphlets carry that library stamp. The catalogue has three main elements: pamphlets and tracts; books, including a section of contemporary biography; and newspapers, journals and conference reports. There are around 1400 separately published pamphlets and tracts but a series of tracts, or part of a series, has usually been catalogued as one item. The Hoyle collection of pamphlets, is bound in 24 volumes, mostly half black roan, many with his ownership stamp. All the pieces from the Joseph Livesey Library are disbound; so that any item described as "disbound" may be assumed to be from the Livesey collection and all the others, for which a volume and item number are given, from Hoyle's bound collection. INTRODUCTION By Brian Harrison Fellow and Tutor in Modern History and Politics, Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Anyone keen to understand the Victorians can hardly do better than devour Joseph Livesey's Staunch Teetotaler (458) or J.G. Shaw's Life of William Gregson. -

Liverpool, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield

Hellifield Lancaster Carlisle Lancaster Carlisle Darlington Scarborough Starbeck Knaresborough Liverpool Leeds Gargrave Ilkley Poulton-le-Fylde Skipton Cattal Hammerton Poppleton Ben Rhydding York Cononley Harrogate Manchester Sheffield Burley-in-Wharfedale Layton Steeton & Silsden Hornbeam Park Otley Principal services are shown as thick lines Clitheroe Kirkham & Keighley Menston Guiseley Pannal Wesham Salwick Local services are shown as thin lines North Limited services are shown as open lines Crossflatts Ulleskelf Whalley Baildon Weeton Blackpool The pattern of services shown is based on the standard Bingley South Mondays to Fridays timetable. At weekends certain Church Fenton stations are closed and some services altered. Langho Saltaire Horsforth Moss Side Airport interchange Shipley St Annes- Ramsgreave & Wilpshire Colne Headingley Blackpool on-the-Sea Pleasure Lytham Preston Tram/Metro Interchange Frizinghall Beach tle Burley Park Southport is Squires Ansdell & w Sherburn-in-Elmet dt Gate Fairhaven al Forster Square New Cross East Selby Gilberdyke sw Nelson Pudsey Bramley Gates Garforth Garforth Micklefield Wressle Howden Eastrington on O Bradford Lostock ht & Hall Bamber is ch Interchange Bridge Pleasington Cherry Tree Mill Hill Blackburn R r on hu gt Meols Cop C rin South Birkdale cc t Leyland A oa Cottingley Leeds Milford nc Brierfield Hull u n H to ve Bescar Lane ap ro Morley Saltmarshe Euxton H G Burnley Central Darwen se Hillside Balshaw Ro Castleford Lane New Lane Halifax Goole Burnley Barracks Woodlesford GlasshoughtonPontefract -

Descendants of Edward HODGSON

Descendants of Edward HODGSON Generation 1 1. EDWARD1 HODGSON . He died. Edward HODGSON had the following children: i. JOHN2 HODGSON was born on 09 Mar 1580/81 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). He died. 2. ii. THOMAS HODGSON was born on 23 Dec 1582 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). He died. He married Ann BREWSTER, daughter of William BREWSTER, on 28 Oct 1606 in Featherstone, Yorkshire. She was born on 06 May 1582 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). She died. 3. iii. ELIZA HODGSON was born on 04 Nov 1587 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). She died. She married Jo INGLE on 04 Nov 1610 in Featherstone, Yorkshire. iv. FRANCES HODGSON was born on 22 Aug 1590 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). She died. v. ROBERT HODGSON was born on 03 Oct 1593 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). He died. 4. vi. MARY HODGSON was born on 11 May 1597 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). She died. She married William THRESH on 30 Jun 1622 in Featherstone, Yorkshire. He was born about 1600. He died in May 1644 in Aketon, Featherstone, Yorkshire. Generation 2 2. THOMAS2 HODGSON (Edward1) was born on 23 Dec 1582 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). He died. He married Ann BREWSTER, daughter of William BREWSTER, on 28 Oct 1606 in Featherstone, Yorkshire. She was born on 06 May 1582 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). She died. Thomas HODGSON and Ann BREWSTER had the following children: i. JANE3 HODGSON was born on 23 Apr 1609 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). ii. MARGARET HODGSON was born on 28 Jan 1611/12 in Featherstone, Yorkshire (bapt.). She married Richard WILDMAN on 20 Aug 1633 in Pontefract, Yorkshire. -

Divisonal Secretaries Teams Report

Divisonal Secretarys Team Report for U11 Divisional Secrectary Aaron Jackson Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07817) 699895 Team ID Number Name Ground Games played at Home Colours Shirt-Shorts-Socks Division Squad 774 Altofts Juniors F.C. (Blue) St Wilfrids Catholic High School Cutsyke Road Featherstone Pontefract WF7 6BD Black / Red Stripes - Black - Black N/A Contact :- Manager Paul Murray Email :- [email protected] Phone :- (01924) 629706 Mobile :- (07883) 016247 493 Altofts Juniors F.C. (Red) St Wilfrids Catholic High School Cutsyke Road Featherstone Pontefract WF7 6BD Red - Black - Red N/A Contact :- Manager Damian Fox Email :- [email protected] Phone :- (01977) 667755 Mobile :- (07800) 772025 336 Alwoodley Juniors F.C. Alwoodley Community Association The Avenue Alwoodley Leeds LS17 7NZ Blue - Blue - Blue N/A Contact :- Manager Mick Baker Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07961) 851908 523 Amaranth Juniors F.C. Amaranth Football Club Manston Lane Crossgates Leeds LS15 8AB Purple - Purple - Purple N/A Contact :- Manager Martin Chandler Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07725) 108905 842 Beeston Juniors F.C. (Blues) Cardinal Square Beeston Leeds LS11 8HS Royal Blue / White Stripes - Royal Blue - Royal Blue N/A Contact :- Manager Philip George Email :- [email protected] Phone :- ( 0113) 2109175 Mobile :- (07894) 053687 472 Beeston Juniors F.C. Yellows Cardinal Square Beeston Leeds LS11 8HS Royal Blue / White Stripes - Royal Blue - Royal Blue N/A Contact :- Manager Philip George Email :- [email protected] Phone :- ( 0113) 2109175 Mobile :- (07894) 053687 810 Carlton & Rothwell Giants JFC Thorpe Recreation Ground Station Lane Thorpe Wakefield WF3 3DY Yellow With Black Trim - Black With Yellow Trim - Black With Yellow N/A Trim Contact :- Manager Philip Blackburn Email :- [email protected] Phone :- Mobile :- (07969) 383615 860 Chapeltown Juniors F.C. -

The London Gazette, November 25, 1881. 6001

THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 25, 1881. 6001 sidings, works, and conveniences connected there- north-west of the booking office of the _ with (that is to say) : Keighley Station; Two railways (to be called " the Snydale A railway to be called "the Swansea Vale Branches"):— Widening," commencing in the township of No. 1, commencing in the township of Warm- Llansamlet Lower in the parish of Llan- field-cum-Heath, in the parish of Warmfield, saml'lt, in the county of Glamorgan, by a in the West Riding of the county of York, junction with the Company's Swansea by a junction with the Company's main Vale Railway at a point thereon two chains line of railway at a point thereon two or thereabouts north-east of the booking- chains or thereabouts north-east of the office 9f the Upper Bank Station, and ter- bridge carrying Hell-lane over that rail- minating in the Parish of Llangiwg, in the way and terminating in the township of same county, by a junction with the said Ackton, in the parish of Featherstone, by a Swansea Vale Railway, at a point thereon .junction with the Colliery Sidings of twenty-four chains or thereabouts north-east Messrs. Henry Briggs, Son, and Company, of the booking-office of the Ystalyfera Station, Limited, near their "Don Pedro" Pit which said intended railway will pass from, abutting upon and on the east side of in, through, or into, or be situate within Havertop-lane ; the several parishes, townships, and extra- parochial or other places following, or some •No. -

St John Fisher Catholic High School Newsletter 19 8 July 2016

St John Fisher Catholic High School Newsletter 19 8 July 2016 Dear Parent / Carer, The last couple of weeks have been the busiest of the year for visits and trips. Amongst others, we had Year 8 students at Ford Castle, a trip to Sorrento, a trip to Iceland, a trip to Brussels, visits to Oxford and Cambridge, and the Lourdes Pilgrimage. This week we have the performance of Bugsy Malone. We also have the Year 8 trip to the Somme coming up as well as Salamanca and the Ardeche. I would like to thank parents for their support; and the staff for giving up their time to take these trips and visits. I am sure that the students involved gain a great deal from the variety of experiences. This week we also welcomed the new Year 7 students on their transition days. We are looking forward to starting work with the next cohort of students, and settling them into the school routines. Great Yorkshire Show You will be aware that the whole school visits the show on 12 July 2016. As all year groups attend the show there is limited provision back in school. If you have not yet done so, can you make arrangements for your child to purchase a ticket which is now £10, deadline for payment is Friday 8 July, 1pm. Please ask your child to take the payment to Mrs Ball in the Goldfish Bowl as it has now been taken off ParentPay. Buses Our Transport page is getting longer and longer. Remember, you have to contact the operator for a pass on services from September 2016. -

We Are Gathering Data to Establish If There Has Been a Significant Increase in the Number of Dogs/Puppies Reported Stolen So Far This Year

We are gathering data to establish if there has been a significant increase in the number of dogs/puppies reported stolen so far this year. Therefore, please can you send me a monthly breakdown of dog theft reports your force has received in the FIVE years to 31st July 2020? If possible can you please also state the number of dogs that were taken in each report? Please see the attached document. Stolen dogs, 01/08/2015 to 31/07/2020 Notes Data represents the number of crimes recorded during the period which: - were not subsequently cancelled - had a 'DOG' property sub type item linked as 'STOLEN' or 'TAKEN' One crime may involve multiple animals being stolen, where known this has been shown - this represents the number of linked property items - one 'item' may refer to multiple animals Records have been manually checked to identify breed of dog(s) These figures may be subject to further investigation, reclassification and cancelling and will therefore change over time Crime classifications based on Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime https://www.gov. -

Adopted Children Need Closer Ties to Their Birth Families, According to National Enquiry 5 March 2018

Adopted children need closer ties to their birth families, according to national enquiry 5 March 2018 Mills of Leeds University as research assistant. After interviewing large numbers of social workers, birth family members, adoptive parents and adopted people plus lawyers and other professionals, the team issued a wide-ranging report, launched in London. Now, it is planned to hold similar events around the UK, so that interested parties throughout the country have a chance to hear and discuss the issues. One of the events will be in Huddersfield, which provided many of the case studies that informed the 44-page report. The document makes five key Professor Brid Featherstone. Credit: University of recommendations, and these have all been Huddersfield accepted by the BASW in its published response. One recommendation was that the current model of adoption should be reviewed, and the potential for Research headed by a University of Huddersfield a more open approach considered. This led the professor has caused an influential social work BASW to call for "a review of adoption law in all organisation to call for a major review of UK countries of the UK, into whether the assumptions adoption law, so that children who have been about severance of connection to families of origin adopted could retain much closer contact with their is ethical". birth families. Also, it is questioned whether the "assumption of In England, Scotland and Wales, direct contact - severance" is sustainable in the age of internet and more commonly allowed in Northern Ireland - is social media, making it much easier for adopted rarely an option.