Glorious Precedents: When Gay Marriage Was Radical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(DE)SUBJUGATED KNOWLEDGES.Pdf

(De)Subjugated Knowledges An Introduction to Transgender Studies Susan Stryker In , I found myself standing in line for my turn at the microphone in the Proshansky Auditorium of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. I was attending a conference called “Lesbian and Gay History,” organized by the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS). I had just attended a panel discussion on “Gender and the Homosexual Role,” moderated by Randolph Trumbach, whose speakers consisted of Will Roscoe, Martha Vicinus, George Chauncey, Ramon Gutierrez, Elizabeth Kennedy, and Martin Manalansan. I had heard a great many interesting things about fairies and berdaches (as two-spirit Native Americans were still being called), Corn Mothers and molly-houses, passionate female friendships, butch-femme dyads, and the Southeast Asian gay diaspora, but I was nevertheless standing in line to register a protest. Each of the panelists was an intellectual star in his or her own right, but they were not, I thought, taken collectively, a very gender- diverse lot. From my perspective, with a recently claimed transsexual identity, they all looked pretty much the same: like nontransgender people. A new wave of transgender scholarship, part of a broader queer intellectual movement was, by that point in time, already a few years old. Why were there no transgender speakers on the panel? Why was the entire discussion of “gender diversity” subsumed within a discussion of sexual desire—as if the only reason to express gender was to signal the mode of one’s attractions and availabilities to potential sex partners? As I stood in line, trying to marshal my thoughts and feelings into what I hoped would come across as an articulate and eloquent critique of gay historiography rather than a petulant complaint that no- body had asked me to be on that panel, a middle-aged white man on the other side of the auditorium reached the front of the other queue for the other microphone and began to speak. -

LGBT History Month 2016

Inner Temple Library LGBT History Month 2016 ‘The overall aim of LGBT History Month is to promote equality and diversity for the benefit of the public. This is done by: increasing the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (“LGBT”) people, their history, lives and their experiences in the curriculum and culture of educational and other institutions, and the wider community; raising awareness and advancing education on matters affecting the LGBT community; working to make educational and other institutions safe spaces for all LGBT communities; and promoting the welfare of LGBT people, by ensuring that the education system recognises and enables LGBT people to achieve their full potential, so they contribute fully to society and lead fulfilled lives, thus benefiting society as a whole.’ Source: www.lgbthistorymonth.org.uk/about Legal Milestones ‘[A] wallchart has been produced by the Forum for Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Equality in Further and Higher Education and a group of trade unions in association with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (LGBT) History Month. The aim has been to produce a resource to support those raising awareness of sexual orientation and gender identity equality and diversity. Centred on the United Kingdom, it highlights important legal milestones and identifies visible and significant contributions made by individuals, groups and particularly the labour movement.’ Source: www.lgbthistorymonth.org.uk/wallchart The wallchart is included in this leaflet, and we have created a timeline of important legal milestones. We have highlighted a selection of material held by the Inner Temple Library that could be used to read about these events in more detail. -

Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet: Establishing Conditions for Lesbian and Gay Intimacy, Nomos, and Citizenship, 1961-1981 William N

Hofstra Law Review Volume 25 | Issue 3 Article 7 1997 Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet: Establishing Conditions for Lesbian and Gay Intimacy, Nomos, and Citizenship, 1961-1981 William N. Eskridge Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eskridge, William N. Jr. (1997) "Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet: Establishing Conditions for Lesbian and Gay Intimacy, Nomos, and Citizenship, 1961-1981," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 25: Iss. 3, Article 7. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol25/iss3/7 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eskridge: Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet: Establishing Conditions CHALLENGING THE APARTHEID OF THE CLOSET: ESTABLISHING CONDITIONS FOR LESBIAN AND GAY INTIMACY, NOMOS, AND CITIZENSHIP, 1961-1981 William N. Eskridge, Jr.* CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................... 819 I. PROTECTING PRIVATE GAY SPACES: DuE PROCESS AND FOURTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS ....................... 828 A. Due Process Incorporationof the Bill of Rights (CriminalProcedure) ....................... 830 1. The Warren Court's Nationalization of the Rights of Criminal Defendants .............. 830 2. Criminal Procedural Rights as Protections for Homosexual Defendants ....... 832 3. Criminal Procedural Rights and Gay Power ..... 836 B. Substantive Due Process and Repeal or Nullification of Sodomy Laws (The Right to Privacy) .......... 842 C. Vagueness and Statutory Obsolescence ........... 852 1. Sodomy Laws ......................... 855 2. Lewdness and Sexual Solicitation Laws ....... 857 3. -

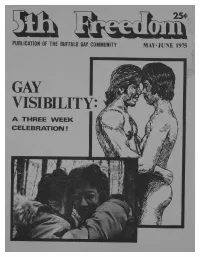

Visibility: a Three Week I I Celebration! I \ Editorial 3 from Our Mailbag 3 Review: Funny Lady 5

5thFreedom 25* PUBLICATION OF THE BUFFALO GAY COMMUNITY MAY-JUNE 1975 GAY VISIBILITY: A THREE WEEK I I CELEBRATION! I \ EDITORIAL 3 FROM OUR MAILBAG 3 REVIEW: FUNNY LADY 5 GAY VISIBILITY. , T , Tr 6 hy Don Michaels-Johnn Yanson A THREE WEEK CELEBRATION 8 DO GAY MEN RAPE LESBIANS? OR SEXISM:AN OBSTACLE TO GAY 11 UNITY "by Heather Koeppel ENTERTAINMENT 12 GAY TALK: THE CHANGING TIMESI4 DEAR BLABBY 16 REACHING OUT TO GAY ALCOHOLICS by Don Michaels 17 POETRY 19 WRITE ON! BRITTANICA 20 BY Madeline Davis A TALE OF THREE SISTERS: A FEMINIST FABLE 21 BY Sue Whitson Circulation 3000. Editor-Dane Winters ,; Asst. Editor-Dave Wunz , Creative Director-Greg Bodekor, Art Director-John Yanson, General Manager-Don Michaels, Services Editor-Dorm Holley, Photographer- Joanne Britten, Contributors-Linda Jaffey, Jim Weiser, Marcia Klein, Heather Koeppel, Doug Randolph and Benji. Cover design by Greg Bodekor. Address all material to FIFTH FREEDOM, P.O. Box 975, Ellicott Sta., Bflo., NY 14205. FIFTH FREEDOM is published at 1550 Main St. and printed by October Graphics, 1207 Hertel Aye. Refer questions to Gay Center 881-5335. All rights reserved and reproduction without permission is strictly prohibited. 2 EDITORIAL This is the first issue condoning the very things we tions of any kind to our ef- of the Fifth Freedom in its are working to end; prejudice, fort. The only talent you new format. It's significant oppression and non-acceptance. need is a real concern about that we have made this tran- We believe our new format our effort. The only quali- sition at the same time that will give us the means to .ex- fication we require of our Mattachine is celebrating its plore areas of graphic presen- staff is a willingness to work fifth year of Gay Pride with tation that we could not try with us in whatever way they, the theme GAY VISIBILITY. -

SEXUAL ORIENTATION and GENDER IDENTITY October 2, 2019 10336 ICLE: State Bar Series

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER IDENTITY October 2, 2019 10336 ICLE: State Bar Series Wednesday, October 2, 2019 SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER IDENTITY 6 CLE Hours Including | 1 Professionalism Hour Copyright © 2019 by the Institute of Continuing Legal Education of the State Bar of Georgia. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ICLE. The Institute of Continuing Legal Education’s publications are intended to provide current and accurate information on designated subject matter. They are off ered as an aid to practicing attorneys to help them maintain professional competence with the understanding that the publisher is not rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. Attorneys should not rely solely on ICLE publications. Attorneys should research original and current sources of authority and take any other measures that are necessary and appropriate to ensure that they are in compliance with the pertinent rules of professional conduct for their jurisdiction. ICLE gratefully acknowledges the eff orts of the faculty in the preparation of this publication and the presentation of information on their designated subjects at the seminar. The opinions expressed by the faculty in their papers and presentations are their own and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the Institute of Continuing Legal Education, its offi cers, or employees. The faculty is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. -

The Equal Rights Review

The Equal Rights Review Promoting equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice In this issue: ■ Special: Detention and discrimination ■ Gender identity jurisprudence in Europe ■ The work of the South African Equality Courts ■ Homophobic discourses in Serbia ■ Testimony from Malaysian mak nyahs The Equal Rights Review Volume Seven (2011) Seven Volume Review Rights The Equal Biannual publication of The Equal Rights Trust Volume Seven (2011) Contents 5 Editorial Detained but Equal Articles 11 Lauri Sivonen Gender Identity Discrimination in European Judicial Discourse 27 Rosaan Krüger Small Steps to Equal Dignity: The Work of the South African Equality Courts 44 Isidora Stakić Homophobia and Hate Speech in Serbian Public Discourse: How Nationalist Myths and Stereotypes Influence Prejudices against the LGBT Minority Special 69 Stefanie Grant Immigration Detention: Some Issues of Inequality 83 Amal de Chickera Draft Guidelines on the Detention of Stateless Persons: An Introductory Note 105 The Equal Rights Trust Guidelines on the Detention of Stateless Persons: Consultation Draft 117 Alice Edwards Measures of First Resort: Alternatives to Immigration Detention in Comparative Perspective Testimony 145 The Mak Nyah of Malaysia: Testimony of Four Transgender Women Interview 157 Equality and Detention: Experts’ Perspectives: ERT talks with Mads Andenas and Wilder Tayler Activities 179 The Equal Rights Trust Advocacy 186 Update on Current ERT Projects 198 ERT Work Itinerary: January – June 2011 4 The Equal Rights -

Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music's

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 #Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture Gabriella Saporito [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Musicology Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Saporito, Gabriella, "#Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8074. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8074 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture Gabriella Saporito Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D., Chair Jennifer Walker, Ph.D. Matthew Heap, Ph.D. -

Film, Video, and Multimedia Reviews Reviews of Short Films

Vol. 63, No. 2 Ethnomusicology Summer 2019 Film, Video, and Multimedia Reviews Reviews of Short Films his issue exclusively features reviews of short films (under thirty minutes). TBecause of the primacy given to feature films in both reviews and distribu- tion, shorts often fly under our radar. Shorts offer a few benefits for ethnomu- sicologists. Due to their length, they may be more feasibly used in a classroom. They can offer a concise audiovisual complement to text- based scholarship. Shorts are also a promising format for ethnomusicologists moving into film- based scholarship or film analysis. (Consider the differences of complexity and effort between a monograph and an essay.) Shorts are also more at home on the internet and at film festivals. They are generally accessible by contacting the filmmakers themselves. Benjamin Harbert, Review Editor, Film, Video, and Multimedia Reviews Worth repeating! Produced, directed, filmed, and edited by Miranda Van der Spek. Sound recording by Miranda Van der Spek and Robert Bosch. Sound mixing by Robert Bosch. Stichting CineMusica in collaboration with Miran- das filmproducties. French with English subtitles. Digital download, color, 28 mins., 2011. Contact: [email protected]. Worth repeating! (2011) by Dutch filmmaker and visual anthropologist Miranda Van der Spek, has been screened recently at the last symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Audiovisual Ethnomusicology in Lisbon and the Ethnomusicological Film Festival in Florence. This short documentary focuses on the instrumental music of the Ouldémé, an agricultural ethnic group living in the Mandara Mountains, in the north of Cameroon, and in particular on the panpipes and their relation with daily life, especially the production of millet. -

September 2006.Pub

Lambda Philatelic PUBLICATION OF THE GAY AND LESBIAN HISTORY ON STAMPS CLUB Journal Ï SEPTEMBER 2006, VOL. 25, NO. 2, WHOLE NO. 95 Plus the final installment of Paul Hennefeld’s Handbook Update September 2006, Whole No. 95, Vol. 25, No. 3 The Lambda Philatelic Journal (ISSN 1541-101X) is published MEMBERSHIP: quarterly by the Gay and Lesbian History on Stamps Club (GLHSC). GLHSC is a study unit of the American Topical As- Yearly dues in the United States, Canada and Mexico are sociation (ATA), Number 458; an affiliate of the American Phila- $10.00. For all other countries, the dues are $15.00. All checks should be made payable to GLHSC. telic Society (APS), Number 205; and a member of the American First Day Cover Society (AFDCS), Number 72. Single issues $3. The objectives of GLHSC are to promote an interest in the col- There are two levels of membership: lection, study and dissemination of knowledge of worldwide philatelic material that depicts: 1) Supportive, your name will not be released to APS, ATA or AFDCS, and 2) Active, your name will be released to APS, ATA and 6 Notable men and women and their contributions to society AFDCS (as required). for whom historical evidence exists of homosexual or bisex- ual orientation, Dues include four issues of the Lambda Philatelic Journal and 6 Mythology, historical events and ideas significant in the his- a copy of the membership directory. (Names will be with- tory of gay culture, held from the directory upon request.) 6 Flora and fauna scientifically proven to having prominent New memberships received from January through September homosexual behavior, and will receive all back issues and directory for that calendar 6 Even though emphasis is placed on the above aspects of year. -

STONEWALL INN, 51-53 Christopher Street, Manhattan Built: 1843 (51), 1846 (53); Combined with New Façade, 1930; Architect, William Bayard Willis

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 23, 2015, Designation List 483 LP-2574 STONEWALL INN, 51-53 Christopher Street, Manhattan Built: 1843 (51), 1846 (53); Combined with New Façade, 1930; architect, William Bayard Willis Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan, Tax Map Block 610, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the buildings at 51-53 Christopher Street are situated On June 23, 2015 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Stonewall Inn as a New York City Landmark and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.1). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of the law. Twenty-seven people testified in favor of the designation including Public Advocate Letitia James, Council Member Corey Johnson, Council Member Rosie Mendez, representatives of Comptroller Scott Stringer, Congressman Jerrold Nadler, Assembly Member Deborah Glick, State Senator Brad Hoylman, Manhattan Borough President Gale A. Brewer, Assembly Member Richard N. Gottfried, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, the Real Estate Board of New York, the Historic Districts Council, the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Family Equality Council, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Parks Conservation Association, SaveStonewall.org, the Society for the Architecture of the City, and Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, New York City, as well as three participants in the Stonewall Rebellion—Martin Boyce, Jim Fouratt, and Dr. Gil Horowitz (Dr. Horowitz represented the Stonewall Veterans Association)—and historians David Carter, Andrew Dolkart, and Ken Lustbader. In an email to the Commission on May 21, 2015 Benjamin Duell, of Duell LLC the owner of 51-53 Christopher Street, expressed his support for the designation. -

How Gay Activists Challenged the Politics of Civility by the Smithsonian Institute, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 1,036 Level 1040L

How gay activists challenged the politics of civility By The Smithsonian Institute, adapted by Newsela staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 1,036 Level 1040L Image 1. The city of Raleigh, North Carolina held its first Gay Pride celebration on June 25, 1988. Photo from: Flickr/State Archives of North Carolina. On April 13, 1970, New York Mayor John Lindsay and his wife arrived at the Metropolitan Opera House. It was opening night of the season. The Republican mayor had no idea he was about to be ambushed by members of the newly formed Gay Activist Alliance (GAA). The protesters entered the event in tuxedos and shouted, "End Police Harassment!" and "Gay Power!" A year earlier, newspaper headlines were covering the Stonewall Riots. These riots happened between members of the gay community and police because of a raid at the Stonewall Inn. The Inn was a gay bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan. For most of the 20th century, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) Americans were unwelcome in society. They were forced to hide their sexuality, and many laws prohibited their activities. In the 1970s things began to change. Employment Discrimination This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. Lindsay had refused to enact a citywide anti-discrimination law after the riots. During the next two years, gay rights activists confronted the mayor in public. In 1972 Lindsay finally relented. He signed an executive order to forbid discriminating against job candidates for city government jobs based on sexual orientation. For the next three decades the gay liberation movement continued to confront public figures. -

Gay Rights Law and Public Policy / Susan Gluck Mezey

MEZEY LAW • POLITICS “Queers in Court is an excellent history of gay rights litigation in the U.S. It is thorough and yet readable. It covers topics ranging from marriage to the military, it covers them over an entire cen- tury of American history, it appreciates their nuances, and it places litigation in the context of pub- lic opinion. Queers in Court would be useful in a college or law school classroom and it would also be good company on a long plane flight. In one volume, it provides a solid, well-rounded, easily- QUEERS IN COURT digested introduction to all of gay law.” —William Rubenstein, UCLA School of Law; founding director, Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation Law; and former director, ACLU Lesbian and Gay Rights Project “I learned a lot from reading Queers in Court, and expect to consult it many times. The book is QUEERS IN COURT must reading for students of gay and lesbian politics, but it will also be useful for anyone inter- ested in social movements in the American courts. It provides that rare balance of a broad per- spective that still includes all of the details specialists require.” —Clyde Wilcox, Georgetown University “Queers in Court is a meticulously researched survey of gay rights cases in state and federal courts over the last fifty years. Susan Gluck Mezey provides a comprehensive and richly detailed reference that is indispensable to understanding the interplay in American policymaking among judges, other legal and political elites, and public opinion. A truly enlightening book.” —Daniel R. Pinello, author of Gay Rights and American Law and America’s Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage SUSAN GLUCK MEZEY is professor of political science and assistant vice president for research at Loyola University Chicago.