Hebrew Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews on Route to Palestine 1934-1944. Sketches from the History of Aliyah

JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 JAGIELLONIAN STUDIES IN HISTORY Editor in chief Jan Jacek Bruski Vol. 1 Artur Patek JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 Sketches from the History of Aliyah Bet – Clandestine Jewish Immigration Jagiellonian University Press Th e publication of this volume was fi nanced by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow – Faculty of History REVIEWER Prof. Tomasz Gąsowski SERIES COVER LAYOUT Jan Jacek Bruski COVER DESIGN Agnieszka Winciorek Cover photography: Departure of Jews from Warsaw to Palestine, Railway Station, Warsaw 1937 [Courtesy of National Digital Archives (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe) in Warsaw] Th is volume is an English version of a book originally published in Polish by the Avalon, publishing house in Krakow (Żydzi w drodze do Palestyny 1934–1944. Szkice z dziejów alji bet, nielegalnej imigracji żydowskiej, Krakow 2009) Translated from the Polish by Guy Russel Torr and Timothy Williams © Copyright by Artur Patek & Jagiellonian University Press First edition, Krakow 2012 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any eletronic, mechanical, or other means, now know or hereaft er invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers ISBN 978-83-233-3390-6 ISSN 2299-758X www.wuj.pl Jagiellonian University Press Editorial Offi ces: Michałowskiego St. 9/2, 31-126 Krakow Phone: +48 12 631 18 81, +48 12 631 18 82, Fax: +48 12 631 18 83 Distribution: Phone: +48 12 631 01 97, Fax: +48 12 631 01 98 Cell Phone: + 48 506 006 674, e-mail: [email protected] Bank: PEKAO SA, IBAN PL80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 Contents Th e most important abbreviations and acronyms ........................................ -

OBITUARIES Picked up at a Comer in New York City

SUMMER 2004 - THE AVI NEWSLETTER OBITUARIES picked up at a comer in New York City. gev until his jeep was blown up on a land He was then taken to a camp in upper New mine and his injuries forced him to return York State for training. home one week before the final truce. He returned with a personal letter nom Lou After the training, he sailed to Harris to Teddy Kollek commending him Marseilles and was put into a DP camp on his service. and told to pretend to be mute-since he spoke no language other than English. Back in Brooklyn Al worked While there he helped equip the Italian several jobs until he decided to move to fishing boat that was to take them to Is- Texas in 1953. Before going there he took rael. They left in the dead of night from Le time for a vacation in Miami Beach. This Havre with 150 DPs and a small crew. The latter decision was to determine the rest of passengers were carried on shelves, just his life. It was in Miami Beach that he met as we many years later saw reproduced in his wife--to-be, Betty. After a whirlwind the Museum of Clandestine Immigration courtship they were married and decided in Haifa. Al was the cook. On the way out to raise their family in Miami. He went the boat hit something that caused a hole into the uniform rental business, eventu- Al Wank, in the ship which necessitated bailing wa- ally owning his own business, BonMark Israel Navy and Palmach ter the entire trip. -

Reverend John Stanley G Rauel

Reverend John Stanley Grauel Whatever your faith or beliefs, you cannot help but be deeply moved by John Grauel's story of his dramatic life, a Christian minister who became a founding father of Israel, a pacifist who fought in what he came to feel was a more noble cause. • David Schoenbaum, author broadcaster Reverend John Stanley Grauel was a Methodist what business he was in. He said he was interviewing Minister who served as a secret Haganah operative counselors for camp. “If those tough looking guys were on the famed Jewish Holocaust Refugee ship, Exodus counselors, I’d like to meet the campers,” was my re- ’47.1Later in his life, when his health and finances were sponse. Bucky invited me for lunch, which I this case particularly bad, he wrote his autobiography in which meant sandwiches at his desk, and we talked. I found he he explains how he became involved with the Haga- had been informed about my work next door, even if I nah. had not been told about his. He was running a recruit- 2 ing office for the Haganah here in the States. “Perhaps it was my discontent that made me notice the activists of others, but when I returned to Philadel- ...Talking to Bucky, I knew I had found my niche. I phia, I began to be aware of the stream of young men would join the Haganah, the underground, going in and out of the next office. I have always exer- cised more than my share of curiosity, nurtured through to become a part of that organization to rescue those 3 the years by the fact that people hesitate to punch a cler- who could be helped to leave Europe. -

AVILC Summer 2013

SUMMER 2013 AMERICAN VETERANS OF ISRAEL LEGACY CORPORATION PRESERVING THE LEGACY OF AMERICAN AND CANADIAN VOLUNTEERS IN ISRAEL’S WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 136 East 39th Street, New York, NY 10016 The President’s Corner 2013 MICKEY MARCUS MEMORIAL Dear Friends, AT WEST POINT Welcome to the latest AVILC Aliyah Bet Veterans Honored Amid Family, Military, Newsletter and thanks to our and Israeli VIPs Editor, Elizabeth Appley and By Elizabeth J. Appley writer, Si Spiegelman, for yeoman AVILC’s annual Mickey Marcus the 65th anniversary of Israel’s duties in putting it together. Memorial Service at the United independence and the 65th We’ve had an eventful year States Military Academy at West yartzheit of Aluf Michael highlighted by an exceptional 2013 (Mickey) Stone, z”l, in Mickey Marcus Memorial event whose memory the event at West Point again ably organized is named. A special by Si Spiegelman and Rafi Marom, tribute honored the North with wonderful assistance from American Aliyah Bet Donna Parker. The theme was to veterans who ran the honor the Members of Aliyah Bet clandestine immigration who brought thousands of Shoah s h i p s s m u g g l i n g survivors to Eretz Yisrael and European Jews into contributed to breaking the British mandate Palestine. rule there. We were honored to The service at the West have in attendance Ambassador Point Jewish Chapel was Ido Aharoni, Consul General of called to order by AVILC Israel in NY, military dignitaries, Director, Rafi Marom. members of the Marcus family, Donna Parker Photo credit: West Point Cadets Ford and Topp assisting Colonel After the posting of the Aliyah Bet veterans, Machalniks Charles Stafford, Chief of Staff for the colors and the singing of and family and friends. -

The SS Ben Hecht

1 The S.S. Ben Hecht "The Mandate of Conscience" By Judith Rice Ben Hecht1 S.S. Ben Hecht shadowed by the British Navy She is the last ship afloat; the last man standing from the fight. She was the ship of the outcasts, the rejected, the despised. Jewish leadership, afraid to disturb, he cried out for the dying. The Aliyah Bet veterans are almost all gone now, passing under the grey waves of lapping history and forgetfulness. Peter Bergson & 1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ben_Hecht 2 Ben Hecht’s struggle to save Jewish lives is still deliberately obscured, to protect the ethos, the myths of Jewish/Zionist leadership. As the blackening blood colored clouds of the coming Holocaust gathered before 1939, Europe’s Jews were desperate for refuge. No one wanted Jews, not even America. The famed words of the Jewish poetess Emma Lazarus2 on the Statue of Liberty in New York’s harbor, "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest- tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!" were meaningless. The American lamp was not lit for European Jewry. The door was tightly closed. The only place that did want them was the promised Jewish national home in Palestine, the Palestine of the Balfour Declaration3. The League of Nations4 British Mandate for Palestine envisioned for possible Jewish settlement encompassed 43,000 square miles. The size of the Jewish national home was massively reduced in 1922. Winston Churchill signed the severance of 32,500 square miles from the Palestine Mandate area. -

The United States Navy and Israeli Navy Background, Current Issues, Scenarios, and Prospects

The United States Navy and Israeli Navy Background, current issues, scenarios, and prospects Dov S. Zakheim Cleared for Public Release COP D0026727.A1/Final February 2012 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “problem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the following areas: • The full range of Asian security issues • The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf • Maritime strategy • Insurgency and stabilization • Future national security environment and forces • European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral • West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea • Latin America • The world’s most important navies • Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

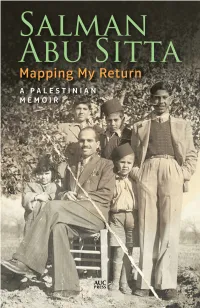

Mapping My Return

Mapping My Return Mapping My Return A Palestinian Memoir SALMAN ABU SITTA The American University in Cairo Press Cairo New York This edition published in 2016 by The American University in Cairo Press 113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt 420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 www.aucpress.com Copyright © 2016 by Salman Abu Sitta All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Exclusive distribution outside Egypt and North America by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd., 6 Salem Road, London, W2 4BU Dar el Kutub No. 26166/14 ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abu Sitta, Salman Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir / Salman Abu Sitta.—Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2016 p. cm ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 1. Beersheba (Palestine)—History—1914–1948 956.9405 1 2 3 4 5 20 19 18 17 16 Designed by Amy Sidhom Printed in the United States of America To my parents, Sheikh Hussein and Nasra, the first generation to die in exile To my daughters, Maysoun and Rania, the first generation to be born in exile Contents Preface ix 1. The Source (al-Ma‘in) 1 2. Seeds of Knowledge 13 3. The Talk of the Hearth 23 4. Europe Returns to the Holy Land 35 5. The Conquest 61 6. The Rupture 73 7. The Carnage 83 8. -

In Pursuit of Mobility

Joonas Sipilä & Tommi Koivula Joonas Sipilä & Tommi National Defence College Department of War History Publication series 1 Tänä päivänä strategian käsitettä käytetään monin eri tavoin niin siviili- kuin sotilasyhteyk- sissäkin. Maanpuolustuskorkeakoulussa stra- tegia katsotaan yhdessä sotahistorian sekä operaatiotaidon ja taktiikan kanssa sotataidon keskeiseksi osa-alueeksi. Oppiaineena strategi- alle on ominaista korkea yleisyyden aste sekä teoreettinen ja menetelmällinen moninaisuus. Tässä teoksessa pitkäaikaiset strategian tutki- jat ja opettajat, professori Joonas Sipilä ja YTT KUINKA STRATEGIAA TUTKITAAN KUINKA STRATEGIAA Kalle Kirjailija Tommi Koivula, valottavat kokonaisvaltaisesti strategian tutkielman kirjoittamiseen liittyviä In Pursuit of Mobility ulottuvuuksia edeten alan tieteenfilosofiasta aina tutkimusasetelman rakentamiseen, tutki- musmenetelmiin sekä konkreettiseen kirjoitta- The Birth and Development of Israeli mistekniikkaan ja tutkielman viimeistelyohjei- siin. Operational Art. Julkaisu on tarkoitettu avuksi erityisesti pro From Theory to Practice. gradun tai diplomityön kirjoittamisessa vas- (2. uud. painos) taan tuleviin haasteisiin, mutta teoksesta on hyötyä myös muille strategian tutkimuksesta Pasi Kesseli kiinnostuneille. Julkaisusarja 2 No 52, 2014 Maanpuolustuskorkeakoulu Tel. +358 299 800 ISBN: 978-951-25-2614-7 (nid.) Strategian laitos www.mpkk.fi ISBN: 978-951-25-2615-4 (PDF) PL 7, 00861 HELSINKI ISSN: 1455-2108 Suomi Finland Pasi Kesseli IN PURSUIT OF MOBILITY The Birth and Development of Israeli Operational Art. From Theory to Practice. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in lecture room 13, on the 25th of January, 2002 at 12 o'clock. Pasi Kesseli IN PURSUIT OF MOBILITY The Birth and Development of Israeli Operational Art. From Theory to Practice. National Defence College of Finland, Publication series 1 N:o 6 Cover: Israeli tanks ready for action during the May crisis before the Six Day War. -

The Palyam: Servant and Samurai of Aliya Bet1 Eliezer Tal English Version: Translation – Aryeh Malkin, Review – Yehuda Ben-Tzur

1 The Palyam: Servant and Samurai of Aliya Bet1 Eliezer Tal English version: translation – Aryeh Malkin, review – Yehuda Ben-tzur (Lecture prepared for the convention commemorating “the 50th anniversary of Aliya Bet”, held at the “Soldiers’ House” in Haifa on 20th October 1997) In recent years a number of good research articles have appeared dealing with illegal immigration in general, and the period following the end of WW II in particular. It would be sufficient to mention the “History of the Hagana” and the important publications of “Shaul Avigur's Research Society of Aliya Bet”, and other research works that were published such as: “The Rebellious Vessels”. Other research publications dealt with the activities of more specific groups, such as the Gideonim (wireless communications network); the “Gang”–'Ha'chavura' (Hagana members serving in the British Army); and the Machal – (Aliya Bet volunteers from North America), and more. But in all these various publications you will not find one decent research article on the Palyam as an organic unit containing various elements. The Palyam is often mentioned but not directly nor as the central force in all these activities. We now have the peculiar situation where the vital unit in the success of this whole episode and in the creation of the Israeli Navy and its achievements in the War of independence has still not found its rightful place, nor has its vital contribution to our history been defined. This article is not intended to take the place of an in-depth research work on the Palyam. I intend simply to emphasize a few of the outstanding characteristics of the Palyam that define its specific contribution to the battle for Aliya Bet. -

University of London Thesis

2809076477 REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Name of Author COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written perjnission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. This copy has been deposited in the Library______ of £A..C* ^ This copy has been deposited in the University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. -

Origin of Bluetongue Virus Serotype 8 Outbreak in Cyprus, September 2016

viruses Article Origin of Bluetongue Virus Serotype 8 Outbreak in Cyprus, September 2016 Paulina Rajko-Nenow 1,*, Vasiliki Christodoulou 2, William Thurston 3 , Honorata M. Ropiak 1, Savvas Savva 2, Hannah Brown 1, Mehnaz Qureshi 1, Konstantinos Alvanitopoulos 2, Simon Gubbins 1 , John Flannery 1 and Carrie Batten 1 1 Pirbright Institute, Woking, Surrey GU24 0NF, UK; [email protected] (H.M.R.); [email protected] (H.B.); [email protected] (M.Q.); [email protected] (S.G.); john.fl[email protected] (J.F.); [email protected] (C.B.) 2 Veterinary Services of Cyprus, Nicosia 1417, Cyprus; [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (K.A.) 3 Met Office, Exeter EX1 3PB, UK; william.thurston@metoffice.gov.uk * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 December 2019; Accepted: 10 January 2020; Published: 14 January 2020 Abstract: In September 2016, clinical signs, indicative of bluetongue, were observed in sheep in Cyprus. Bluetongue virus serotype 8 (BTV-8) was detected in sheep, indicating the first incursion of this serotype into Cyprus. Following virus propagation, Nextera XT DNA libraries were sequenced on the MiSeq instrument. Full-genome sequences were obtained for five isolates CYP2016/01-05 and the percent of nucleotide sequence (% nt) identity between them ranged from 99.92% to 99.95%, which corresponded to a few (2–5) amino acid changes. Based on the complete coding sequence, the Israeli ISR2008/13 (98.42–98.45%) was recognised as the closest relative to CYP2016/01-05. -

Stranded in Boğaz, Cyprus: the Affair of the Pan Ships, January 1948*

Stranded in Boğaz, Cyprus: The affair of the Pan Ships, January 1948* Danny Goldman Michael J K Walsh Eastern Mediterranean University Abstract: This article sheds some new light on the affair of the Pan Crescent and the Pan York, the largest ships to carry ‘illegal’ Jewish immigrants to Palestine from Bulgaria in 1947 / 1948. These ageing vessels were apprehended by the British authorities off the Dardanelles and escorted to an enforced detention near Famagusta, Cyprus. The ships remained anchored near Boğaz for five months while their human cargos were sent to camps just outside the walls of the historic city. As the clock counted down on the British Mandate in Palestine throughout early 1948, the fate of the vessels, and the thousands of immigrants who depended upon them, hung in the balance. Now, through a recently instigated cataloguing project for Cypriot newspapers instigated at the National Archive in Kyrenia, and the simultaneous uncovering of some relevant documents at the Public Records Office in London, a fuller understanding and appreciation of the events in this critical post war period can be attempted. This article is one of a series published in the Journal of Cyprus Studies that draws historical links between Cyprus and the Jewish people.1 Keywords: Cyprus, Famagusta, Jewish Immigration, Palestine, Pan York, Pan Crescent. Özet Bu makale 1947-1948 yıllarında yasadışı Yahudi göçmenlerini Bulgaristan’dan yola çıkıp Kıbrıs üzerinde Filistine götüren Pan Crescent ve Pan York gemilerine ilişkin tarihteki karanlığa yeni bir ışık yakmaktadır. Bu yolculuğun başında bu tarihi gemiler İngiliz yetkililer tarafından Çanakkale * The authors wish to thank Yehuda Ben-Zur; Yoskeh Rom; Naomi Izhar; Dubi Meyer; Allan Langdale; Hawley Wright-Kusch; Merve Arkan; the Palyam on-line historical database www.palyam.org, managed by Y.