Addis Ababa University: Unpublished

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Agricultural Education in the Development of Agriculture in Ethiopia Dean Alexander Elliott Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1957 Role of agricultural education in the development of agriculture in Ethiopia Dean Alexander Elliott Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons, and the Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Elliott, Dean Alexander, "Role of agricultural education in the development of agriculture in Ethiopia " (1957). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1348. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1348 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROLE OP AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE IN ETHIOPIA by Dean Alexander Elliott A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Vocational Education Approved Signature was redacted for privacy. Charge of Major Work Signature was redacted for privacy. Hea Ma^ctr^partrnent Signature was redacted for privacy. Dé ah of Graduate Iowa State College 1957 il TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 COUNTRY AND PEOPLE .... ..... 5 History 5 Geography 16 People 30 Government 38 Ethiopian Orthodox Church lj.6 Transportation and Communication pif. NATIVE AGRICULTURE 63 Soils 71 Crops 85 Grassland and Pasture 109 Livestock 117 Land Tenure 135? GENERAL AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION 162 Organization and Administration 165 Teacher Supply and Teacher Education 175 Schools and Colleges 181}. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

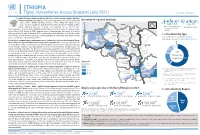

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Regreening of the Northern Ethiopian Mountains: Effects on Flooding and on Water Balance

PATRICK VAN DAMME THE ROLE OF TREE DOMESTICATION IN GREEN MARKET PRODUCT VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 129-147 REGREENING OF THE NORTHERN ETHIOPIAN MOUNTAINS: EFFECTS ON FLOODING AND ON WATER BALANCE Tesfaalem G. Asfaha (1,2), Michiel De Meyere (2), Amaury Frankl (2), Mitiku Haile (3), Jan Nyssen (2) (1) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Mekelle University, Ethiopia (2) Department of Geography, Ghent University, Belgium (3) Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, Ethiopia The hydro-geomorphology of mountain catchments is mainly determined by vegetation cover. This study was carried out to analyse the impact of vegetation cover dynamics on flooding and water balance in 11 steep (0.27-0.65 m m-1) catchments of the western Rift Valley escarpment of Northern Ethiopia, an area that experienced severe deforestation and degradation until the first half of the 1980s and considerable reforestation thereafter. Land cover change analysis was carried out using aerial photos (1936,1965 and 1986) and Google Earth imaging (2005 and 2014). Peak discharge heights of 332 events and the median diameter of the 10 coarsest bedload particles (Max10) moved in each event in three rainy seasons (2012-2014) were monitored. The result indicates a strong re- duction in flooding (R2 = 0.85, P<0.01) and bedload sediment supply (R2 = 0.58, P<0.05) with increas- ing vegetation cover. Overall, this study demonstrates that in reforesting steep tropical mountain catchments, magnitude of flooding, water balance and bedload movement is strongly determined by vegetation cover dynamics. -

Linking Poor Rural Households to Microfinance and Markets in Ethiopia

Linking Poor Rural Households to Microfinance and Markets in Ethiopia Baseline and Mid-term Assessment of the PSNP Plus Project in Raya Azebo November 2010 John Burns & Solomon Bogale Longitudinal Impact Study of the PSNP Plus Program Baseline Assessment in Raya Azebo Table of Contents SUMMARY 6 1. INTRODUCTION 8 1.1 PSNP PLUS PROJECT BACKGROUND 8 1.2 LINKING POOR RURAL HOUSEHOLDS TO MICROFINANCE AND MARKETS IN ETHIOPIA. 9 2 THE PSNP PLUS PROJECT 10 2.1 PSNP PLUS OVERVIEW 10 2.2 STUDY OVERVIEW 11 2.3 OVERVIEW OF PSNP PLUS PROJECT APPROACH IN RAYA AZEBO 12 2.3.1 STUDY AREA GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS 12 2.3.2 MICROFINANCE LINKAGE COMPONENT 12 2.3.3 VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ASSOCIATIONS 13 2.3.4 MARKET LINKAGE COMPONENT 14 2.3.5 IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGES 17 2.4 RESEARCH QUESTIONS 18 3. ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY 19 3.1 STUDY APPROACH 19 3.2 OVERVIEW OF METHODS AND INDICATORS 19 3.3 INDICATOR SELECTION 20 3.4 SAMPLING 20 3.4.1 METHOD AND SIZE 20 3.4.2 STUDY LOCATIONS 21 3.5 DATA COLLECTION METHODS 22 3.5.1 HOUSEHOLD INTERVIEWS 22 3.5.2 FOCUS GROUP METHODS 22 3.6 PRE-TESTING 23 3.7 TRIANGULATION AND VALIDATION 23 3.8 DATA ANALYSIS 23 4 RESULTS 25 4.1 CONTEXTUALIZING PSNP PLUS 25 4.2 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND STATUS AT THE TIME OF THE ASSESSMENT 26 4.3 IMPACT OF THE DROUGHT IN 2009 28 4.4 COMMUNITY CHARACTERISTICS 29 4.5 INCOME AND EXPENDITURE 30 4.5.1 PROJECT DERIVED INCOME AND UTILIZATION 31 4.6 SAVINGS AND LOANS 33 4.6.1 PSNP PLUS VILLAGE SAVINGS GROUPS 34 4.7 ASSETS AND ASSET CHANGES 35 4.8. -

FEWS NET Ethiopia Trip Report Summary

FEWS NET Ethiopia Trip Report Summary Activity Name: Belg 2015 Mid-term WFP and FEWS NET Joint assessment Reported by: Zerihun Mekuria (FEWS NET) and Muluye Meresa (WFP_Mekelle), Dates of travel: 20 to 22 April 2015 Area Visited: Ofla, Raya Alamata and Raya Azebo Woredas in South Tigray zones Reporting date: 05 May 2015 Highlights of the findings: Despite very few shower rains in mid-January, the onset of February to May Belg 2015 rains delayed by more than six weeks in mid-March and most Belg receiving areas received four to five days rains with amount ranging low to heavy. It has remained drier and warmer since 3rd decade of March for more than one month. Most planting has been carried out in mid-March except in few pocket areas in the highlands that has planted in January. About 54% of the normal Belg area has been covered with Belg crops. Planted crops are at very vegetative stage with significant seeds remained aborted in the highlands. While in the lowlands nearly entire field planted with crop is dried up or wilted. Dryness in the Belg season has also affected the land preparation and planting for long cycle sorghum. Although the planting window for sorghum not yet over, prolonged dryness will likely lead farmers to opt for planting low yielding sorghum variety. Average Meher 2014 production has improved livestock feed availability. The crop residue reserve from the Meher harvest is not yet exhausted. Water availability for livestock is normal except in five to seven kebeles in Raya Azebo woreda that has faced some water shortages for livestock. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Agricultural Sciences SEED AID, SMALLHOLDERS, AND THE DEVELOPMENTAL STATE: A MIXED METHODS ANALYSIS OF EMERGENCY RELIEF PROGRAMS IN ETHIOPIA A Dissertation in Rural Sociology & International Agriculture and Development by Christian R. Man © 2018 Christian R. Man Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 The dissertation of Christian R. Man was reviewed and approved* by the following: Leland Glenna Professor of Rural Sociology and Science, Technology, and Society Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian Thiede Assistant Professor of Rural Sociology, Sociology, and Demography Carolyn Sachs Professor Emerita of Rural Sociology Karl Zimmerer Professor of Environment and Society Department of Geography Kathryn J. Brasier Professor of Rural Sociology Director of Graduate Studies in Rural Sociology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT In 2015, El Niño induced the worst drought Ethiopia had seen in fifty years. The resulting crop failures left as many as eighteen million people in need of aid, with one-third of the country’s woredas classified as facing dire food insecurity. Tens of millions of dollars in foreign aid poured into the country in response. A portion of this aid was given as seed to smallholders. Drawing on quantitative and qualitative data collected with farmers in four regions of Ethiopia in 2016 following the aid distributions, this dissertation analyzes how the Ethiopian state and Ethiopian smallholders respectively utilize seed aid. I suggest these utilization strategies coincide, that they serve different ends, and that, together, they illustrate the complex effects of emergency response. -

SITUATION ANALYSIS of CHILDREN and WOMEN: Tigray Region

SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: Tigray Region SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: Tigray Region This briefing note covers several issues related to child well-being in Tigray Regional State. It builds on existing research and the inputs of UNICEF Ethiopia sections and partners.1 It follows the structure of the Template Outline for Regional Situation Analyses. 1Most of the data included in this briefing note comes from the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), Household Consumption and Expenditure Survey (HCES), Education Statistics Annual Abstract (ESAA) and Welfare Monitoring Survey (WMS) so that a valid comparison can be made with the other regions of Ethiopia. SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: TIGRAY REGION 4 1 THE DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT The northern and mountainous region of Tigray has an estimated population of 5.4 million people, of which approximately 13 per cent are under 5 years old and 43 per cent is under 18 years of age. This makes Tigray the fifth most populous region of Ethiopia. Tigray has a relatively high percentage of female-headed households, at 34 per cent in 2018 versus a national rate of 25 per cent in 2016. Three out of four Tigrayans live in rural areas, and most depend on agriculture (mainly subsistence crop farming).4 Urbanization is an emerging priority, as many new towns are created, and existing towns expand. Urbanization in Tigray is referred to as ‘aggressive’, with an annual rate of 4.6 per cent in the Tigray Socio-Economic Baseline Survey Report (2018).5 The annual urban growth -

Ethiopia: Access

ETHIOPIA Access Map - Tigray Region As of 31 May 2021 ERITREA Ethiopia Adi Hageray Seyemti Egela Zala Ambesa Dawuhan Adi Hageray Adyabo Gerhu Sernay Gulo Mekeda Erob Adi Nebried Sheraro Rama Ahsea Tahtay Fatsi Eastern Tahtay Adiyabo Chila Rama Adi Daero Koraro Aheferom Saesie Humera Chila Bzet Adigrat Laelay Adiabo Inticho Tahtay Selekleka Laelay Ganta SUDAN Adwa Edaga Hamus Koraro Maychew Feresmay Afeshum Kafta Humera North Western Wukro Adwa Hahayle Selekleka Akxum Nebelat Tsaeda Emba Shire Embaseneyti Frewoyni Asgede Tahtay Edaga Arbi Mayechew Endabaguna Central Hawzen Atsbi May Kadra Zana Mayknetal Korarit TIGRAY Naeder Endafelasi Hawzen Kelete Western Zana Semema Awelallo Tsimbla Atsibi Adet Adi Remets Keyhe tekli Geraleta Welkait Wukro May Gaba Dima Degua Tsegede Temben Dima Kola Temben Agulae Awra Tselemti Abi Adi Hagere May Tsebri Selam Dansha Tanqua Dansha Melashe Mekelle Tsegede Ketema Nigus Abergele AFAR Saharti Enderta Gijet AMHARA Mearay South Eastern Adi Gudom Hintalo Samre Hiwane Samre Wajirat Selewa Town Accessible areas Emba Alaje Regional Capital Bora Partially accessible areas Maychew Zonal Capital Mokoni Neqsege Endamehoni Raya Azebo Woreda Capital Hard to reach areas Boundary Accessible roads Southern Chercher International Zata Oa Partially accessible roads Korem N Chercher Region Hard to reach roads Alamata Zone Raya Alamata Displacement trends 50 Km Woreda The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 31 May 2021 Sources: OCHA, Tigray Statistical Agency, humanitarian partners Feedback: [email protected] http://www.humanitarianresponse.info/operations/ethiopia www.reliefweb.int. -

Tigray Region As of 28 February 2021

ETHIOPIA Access Snapshot - Tigray Region As of 28 February 2021 Humanitarian partners access to Tigray improved According to the regional Emergency Coordination Centre (ECC) N in February, with a number of requests for the ERITREA in Mekelle, relief food actors were unable to operate in nine ERITREA Badime woredas, seven of which in Central zone, i.e. Adet, Keyhe Tekli, deployment of international aid workers cleared Ethiopia Zala 1000 Km at the Federal level and progress in mobilizing Ambesa Ahsea, Chila, Egela, Hahayle, and Aheferom (Central Zone), in Adi Hageray Gerhu Sernay Dawuhan addition to Neqsege (Southern) and Asgede (North-Western). emergency supplied into the region. Adi Nebried Rama Fatsi Partners reported limited logistic capacity (unavailability of Despite these advancements, the humanitarian and Sheraro Adigrat Yeha Bzet Humera Chila Inticho trucks, private operators refusing to work due to insecurity, access situation within Tigray remains highly restricted as a result Adabay Eastern SUDAN Adwa of continued insecurity, and limited assistance reaching people in North Western Akxum Feresmay Edaga limited storage capacity in rural areas), while the lack of adminis- Nebelat Hamus May Wukro Edaga Arbi tration at local level hampered targeting/monitoring of distribu- need, particularly in rural areas. Kadra Shire Frewoyni Baeker Western Central tions. This notwithstanding, important progress was achieved in Endabaguna Mayknetal Hawzen By early February, mobile communications were re-established in Zana Semema terms of dispatching food through the region. Atsibi Wukro main towns, banking services resumed in Adigrat and Shire (in Adi Remets Edaga May Gaba Selus Hayka The presence of EDF along the northern corridor bordering addition to Mekelle and Alamata). -

World Bank Document

PA)Q"bP Q9d9T rlPhGllPC LT.CIILh THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA Ph,$F&,P f1~77Pq ).rlnPQnlI (*) ETHIOPIAN ROADS AUTHORITY w Port Otflce Box 1770 Addlr Ababa Ethlopla ra* ~3 ~TC1770 nRn nnrl rtms Cable Addreu Hlghways Addlr Ababa P.BL'ICP ill~~1ill,& aa~t+mn nnrl Public Disclosure Authorized Telex 21issO Tel. No. 551-71-70/79 t&hl 211860 PlOh *'PC 551-71-70179 4hb 251-11-5514865 Fax 251-11-551 866 %'PC Ref. No. MI 123 9 A 3 - By- " - Ato Negede Lewi Senior Transport Specialist World Bank Country Office Addis Ababa Ethiopia Public Disclosure Authorized Subject: APL 111 - Submission of ElA Reports Dear Ato Negede, As per the provisions of the timeframe set for the pre - appraisal and appraisal of the APL Ill Projects, namely: Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Aposto - Wendo - Negelle, 2. Gedo - Nekemte, 3. Gondar - Debark, and 4. Yalo - Dallol, we are hereby submitting, in both hard and soft copies, the final EIA Reports of the Projects, for your information and consumption, addressing / incorporating the comments received at different stages from the Bank. Public Disclosure Authorized SincP ly, zAhWOLDE GEBRIEl, @' Elh ,pion Roods Authority LJirecror General FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA ETHIOPIAN ROADS AUTHORITY E1546 v 4 N Y# Dalol W E Y# Kuneba Y# CONSULTANCYBerahile SERVICES S F OR FOR Ab-Ala Y# FEASIBILITY STUDY Y# ENVIRONMENTALAfdera IMPACT ASSESSMENT Megale Y# Y# Didigsala AND DETAILEDYalo ENGINEERING DESIGN Y# Y# Manda Y# Sulula Y# Awra AND Y# Serdo Y# TENDEREwa DOCUMENT PREPARATIONY# Y# Y# Loqiya Hayu Deday -

Family Planning Utilization at First Sexual Initiation and Associated Factors Among High School Youth Female Students in Northern Ethiopia

Family Planning Utilization at First Sexual Initiation and Associated Factors among High School Youth Female Students in Northern Ethiopia Tsega G/Slassie Mekelle University College of Health Sciences Girmatsion Fisseha Mekelle University College of Health Sciences Measho G/Slassie Mekelle University College of Health Sciences Tigst Hagos ( [email protected] ) Mekelle University College of Health Sciences Research Keywords: Sexual Initiation, Family Planning Utilization, Factors associated, Ethiopia Posted Date: September 3rd, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-58847/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/14 Abstract Background: In developing, countries young women have little awareness about safe sex practice and do casual sexual activities. The consequences such as teenage and unplanned pregnancy and birth, unsafe abortion, miscarriages, and maternal deaths due to unsafe sex practice make youth sexuality much more serious and common in developing countries. Therefore, this study aimed to assess family planning, utilization at rst sexual initiation, and associated factors among high school youth female students in Alamata, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Methods: An institution-based cross-sectional study was employed in Alamata town, south Tigray region, Ethiopia from June 01-30, 2019. A Self-administered structured questionnaire was used to collect the data. Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS statistical package version 22. Descriptive statistics, bivariate and multivariable logistic regressions were used to assess the factor associated with family planning utilization at rst sexual initiations. Results: A total of 538 youths female who initiated sexual activities with an average age of 18.2+1. -

Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund 2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund 2016 Annual Report TABLE of CONTENTS Forward by the Humanitarian Coordinator 04 Dashboard – Visual Overview 05 Humanitarian Context 06 Allocation Overview 07 Fund Performance 09 Donor Contributions 12 Annexes: Summary of results by Cluster Map of allocations Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund projects funded in 2016 Acronyms Useful Links 1 REFERENCE MAP N i l e SAUDI ARABIA R e d ERITREA S e a YEMEN TIGRAY SUDAN Mekele e z e k e T Lake Tana AFAR DJIBOUTI Bahir Dar Gulf of Aden Asayita AMHARA BENESHANGUL Abay GUMU Asosa Dire Dawa Addis Ababa Awash Hareri Ji Jiga Gambela Nazret (Adama) GAMBELA A EETHIOPIAT H I O P I A k o b o OROMIA Awasa Omo SOMALI SOUTH S SNNPR heb SUDAN ele le Gena Ilemi Triangle SOMALIA UGANDA KENYA INDIAN OCEAN 100 km National capital Regional capital The boundaries and names shown and the designations International boundary used on this map do not imply official endorsement or Region boundary acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary River between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of Lake South Sudan has not yet been determined. 2 I FOREWORD DASHBOARD 3 FOREWORD FOREWORD BY THE HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR In 2016, Ethiopia continued to battle the 2015/2016 El Niño-induced drought; the worst drought to hit the country in fifty years. More than 10.2 million people required relief food assistance at the peak of the drought in April. To meet people’s needs, the Government of Ethiopia and humanitar- ian partners issued an initial appeal for 2016 of US$1.4 billion, which increased to $1.6 billion in August.