Again and Once More Again Exhibition Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN the LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist Degree, Belarusian State University

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist degree, Belarusian State University, 2001 Master of Arts, Brock University, 2005 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Olga Klimova It was defended on May 06, 2013 and approved by David J. Birnbaum, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Aleksandr Prokhorov, Associate Professor, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, College of William and Mary, Virginia Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Olga Klimova 2013 iii SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES Olga Klimova, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The central argument of my dissertation emerges from the idea that genre cinema, exemplified by youth films, became a safe outlet for Soviet filmmakers’ creative energy during the period of so-called “developed socialism.” A growing interest in youth culture and cinema at the time was ignited by a need to express dissatisfaction with the political and social order in the country under the condition of intensified censorship. I analyze different visual and narrative strategies developed by the directors of youth cinema during the Brezhnev period as mechanisms for circumventing ideological control over cultural production. -

Oak Island Mystery

Oak Island Mystery Mars Stirhaven March 15, 2019 Mars Stirhaven Oak Island Mystery March 15, 2019 1 / 28 • I would like to thank the organizers for giving me this opportunity to present this material. • I promised one of the organizers that I would start the talk wearing the Mexican wrestling mask. • Nearly everyone here knows me and would easily recognize me before the \dramatic" reveal so... Mars Stirhaven Oak Island Mystery March 15, 2019 2 / 28 This will have to suffice... Mars Stirhaven Oak Island Mystery March 15, 2019 3 / 28 Publishing a Book • Since you know me and you know how much I hate writing up anything (except code), you're surely as surprised as I am that I wrote a book. • My Amazon Author Bio says I hate writing (which might be a first for an author) and everything I wrote was absolutely true! • I used a pen name for anonymity concerns and because not divulging my affiliations made the prepub process easier and faster. • I used the Mexican wrestling mask (won in a mathematics contest) and a Gold Bug pendant (also an award) for my Bio pics (for which Facebook has banned my Stirhaven account!). Mars Stirhaven Oak Island Mystery March 15, 2019 4 / 28 Publicizing a Result • It turns out publicizing a result is hard work{especially for someone who doesn't want to do it. • Most of the book reviews have been amazing, especially from the reddit crowd, but I just got my first scathing review. • I wanted to reply and correct all the errors in the review but goodreads, and my wife, continue to strongly suggest that authors should not respond to negative reviews. -

Regina Spektor Kommer Till Hultsfred!

2008-12-16 11:08 CET REGINA SPEKTOR KOMMER TILL HULTSFRED! Med 2006-års album "Begin To Hope" gick Regina Spektor från att vara en hyllad artist på alternativscenen till att bli en guldsäljande världsstjärna. Nu är det klart att Regina Spektor kommer till Hultsfred nästa sommar. Det blir hennes första Sverigespelning på nästan två år. De helgjutna albumen "Soviet Kitsch" och "Begin To Hope" har mutat in den rysk-amerikanska singer/songwritern Regina Spektor som en av nutidens mest hyllade artister. Att hon dessutom är helt fenomenal live har givetvis bidragit till att hennes fanskara stadigt vuxit under de fyra år som gått sen "Soviet Kitsch" först letade sig ut från New Yorks undergroundscen, för att nå ut till en betydligt större internationell publik. Det riktigt stora genombrottet kom med "Begin To Hope" och singeln "Fidelity", som båda två sålt guld i USA. Efter att tidigare i december framför allt ha släppt svenska artister kan Hultsfred nu avslöja att Regina Spektor kommer att uppträda på festivalens största scen Hawaii i sommar. Därmed är den första av festivalens internationella headliners till 2009 bokad. - Regina Spektor är en artist med gränslös talang och ett säreget uttryck som omedelbart skiljer henne från mängden, men i stället för att vila på det erbjuder hon dessutom ett unikt fokus och popsinne i sin musik. Det känns grymt kul att presentera en internationell popakt på Hawaii, och ännu mer kul att presentera en av våra personliga favoriter, säger Åsa Johnsen, bandbokare Hultsfred För tillfället är Regina Spektor i studion och jobbar med sitt kommande album. -

Investigative Files the Secrets of Oak Island Joe Nickell

Investigative Files The Secrets of Oak Island Joe Nickell It has been the focus of "the world's longest and most expensive treasure hunt" and "one of the world's deepest and most costly archaeological digs" (O'Connor 1988, 1, 4), as well as being "Canada's best-known mystery" (Colombo 1988, 33) and indeed one of "the great mysteries of the world." It may even "represent an ancient artifact created by a past civilization of advanced capability" (Crooker 1978, 7, 190). The subject of these superlatives is a mysterious shaft on Oak Island in Nova Scotia's Mahone Bay. For some two centuries, greed, folly, and even death have attended the supposed "Money Pit" enigma. The Saga Briefly, the story is that in 1795 a young man named Daniel McInnis (or McGinnis) was roaming Oak Island when he came upon a shallow depression in the ground. Above it, hanging from the limb of a large oak was an old tackle block. McInnis returned the next day with two friends who-steeped in the local lore of pirates and treasure troves-set to work to excavate the site. They soon uncovered a layer of flagstones and, ten feet further, a tier of rotten oak logs. They proceeded another fifteen feet into what they were sure was a man-made shaft but, tired from their efforts, they decided to cease work until they could obtain assistance. However, between the skepticism and superstition of the people who lived on the mainland, they were unsuccessful. The imagined cache continued to lie dormant until early in the next century, when the trio joined with a businessman named Simeon Lynds from the town of Onslow to form a treasure-hunting consortium called the Onslow Company. -

Sverigefavoriten Regina Spektor Är Tillbaka Med Efterlängtat Album, “What We Saw from the Cheap Seats”

2012-03-15 11:00 CET Sverigefavoriten Regina Spektor är tillbaka med efterlängtat album, “What We Saw From The Cheap Seats”,. Besöker Peace & Love festivalen i sommar. 30 maj släpps det efterlängtade albumet “What We Saw From The Cheap Seats”via Sire/Warner Bros. Records i Sverige. Första singeln “All The Rowboats”finns tillgänglig digitalt nu. På nya albumet återförenas Reginamed sin producent-partner Mikke Elizondo (Eminem, Fiona Apple, Dr Dre), det är Reginas första album sen “Far” som släpptes 2009. Den 21 april släpper Reginatvå ryska låtar, “The Prayer Of François Villon (Molitva)” och “Old Jacket (Stariy Pedjak),” som hon gör till sina egna i exklusiva tolkningar för Record Store Day. Reginahar även fått den stora äran att framföra sitt nya material på turné med Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers på deras USA turné. “What We Saw From The Cheap Seats”spelades in under åtta veckor förra sommaren i Los Angeles. Spektor skrev själv elva av låtarna på albumet. Tillsammans med Elizondo jobbade de fram arrangemanget till låtarna för att få varje låt att stå ut från mängden. De flesta låtarna spelades in live med Spektor bakom pianot och mikrofonen för att sedan i efterhand lägga resten av instrumenten på dessa orginalinspelningar. Elizondo beskriver hur det var att arbeta med albumet ;“Regina Spektor is that rare artist that continues to surprise. Just when you think you have her figured out, she knocks you out with something completely different. It’s that spirit that drives this record. Each song takes you on a journey that only Regina is capable of providing. -

A Hint in the Oak Island Treasure Mystery 457

! : Ro.ss W ilh.elm THE SPANISH IN NOV A SCOTIA IN THE I I SIXTEENTII CENTURY-A HINT IN . ::: I . J i THE OAK ISLAND TREASURE MYSTERY I I i .; Introduction OVER THE PAsT one hundred years one of the standard pirate and treasure seeking stories has been the "Oak Island Mystery." Oak Island is in Mahone Bay, Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia, and is about forty-five miles from Halifax, on the Atlantic Coast. For the past 175 years various groups have been digging on the island for what is believed to be a huge buried pirate or Inca treasure. All efforts to date have been frustrated by the intrusion of unlimited amounts of sea water into the diggings. The sea water enters the "treasure" area through an elaborate system of man-made drains or tunnels, one of which is hundreds of feet long and quilt similar to a stone sewer tunnel. While the findings of the treasure hunters indicate the probable existence of some type of treasure vault on the island, the main purpose of this paper is not to document further the efforts of the treasure hunters beyond what has been set forth in DesBrisay's History of the County of Lunenburg 2 Nova Scotia\ or in Harris' book The Oak Island Mystery , or in the numerous 3 accounts of the efforts in the mass media • The purpose of this paper is to show that there is evidence that seems to indicate that an agent of Philip II of Spain, or one of the other kings of Spain in the sixteenth century, built the Oak Island installation. -

2012 July 31 August 7

NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE STREET DATES: JULY 31 AUGUST 7 ISSUE 16 wea.com 2012 7/31/12 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ORDERS ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP QTY DUE Crosby, Stills & Nash Daylight Again FLE CD 081227972455 19360 $4.98 7/11/12 Gloriana A Thousand Miles Left Behind ERP CD 093624959014 527042 $18.98 7/11/12 Then Again: The David Sanborn Sanborn, David RHI CD 081227972882 531614 $19.98 7/11/12 Anthology (2CD) Smiths, The Hatful Of Hollow (180 Gram Vinyl) RRW A 825646658824 45205 $24.98 7/11/12 What We Saw From The Cheap Seats Spektor, Regina SIR A 093624951896 530373 $24.98 7/11/12 (Vinyl) Last Update: 06/11/12 For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. ARTIST: Crosby, Stills & Nash TITLE: Daylight Again Label: FLE/Flashback - Elektra Config & Selection #: CD 19360 F Street Date: 07/31/12 Order Due Date: 07/11/12 UPC: 081227972455 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $4.98 Alphabetize Under: C TRACKS Compact Disc 1 01 Turn Your Back On Love [Remastered LP Version] 07 Too Much Love To Hide [Remastered LP Version] 02 Wasted On The Way [Remastered LP Version] 08 Song For Susan [Remastered LP Version] 03 Southern Cross [Remastered LP Version] 09 You Are Alive [Remastered LP Version] 04 Into The Darkness [Remastered LP Version] 10 Might As Well Have A Good Time [Remastered LP Version] 05 Delta [Remastered LP Version] 11 Daylight Again [Remastered LP Version] 06 Since I Met You [Remastered LP Version] ALBUM FACTS Genre: Rock ARTIST & INFO Band Members: Graham Nash As members of one of rock’s first supergroups, David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash helped define the Woodstock generation through their peerless harmonies, resonant songwriting and deep commitment to political and social causes. -

Ancestors of Bessie Cone Norton

Ancestors of Bessie Cone Norton Paul Tocci Ancestors of Bessie Cone Norton First Generation 1. Bessie Cone Norton-[2223],1 daughter of Frederick Harrison Norton-[1] and Bessie Ilean Wright-[1112], was born on 21 Mar 1914 in Tusculum, Georgia, died on 5 Oct 1971 in Baltimore (City), Maryland at age 57, and was buried on 8 Oct 1971 in Meadow Ridge Cemetery, Elkridge, MD. General Notes: Grandmom made up her own words including these below. There is no "official" spelings since they were all verbal. The spellings below are phoenetic. koogle: feces. Instead of her kids saying they had to poop, she had them say they had to koogle. Koogle was the brand name for a flavored peanut butter marketed by Kraft Foods. Kraft introduced Koogle in 1971, and discontinued it later that decade. It was available in several flavors, including chocolate , cinnamon, strawberry, vanilla and banana. fewta fanta fiola: something she would chant when she was happy calamagra: bruzzy: soft, fuzzy blanket or sweater used to keep warm goozlum: any gravy like food muzry: person or animal that has a sweet, lovable appearance (that cat has a muzry face) Bessie married Nile August Fish Sr-[2] [MRIN: 3], son of Wilson Fish-[2163] and Melissa Isabel Longmire-[2288], on 23 Apr 1929 in Effingham County, Georgia.2 Marriage Notes: 1 NOTE 1930 United States Federal Census Nile Fish 28 1901 Iowa Head White Election District 15,Baltimore, MD Bessie Fish 16 1913 WifeElection District 15, Baltimore, MD Children from this marriage were: i. Niton Dwight Fish-[113] ii. -

Balancing Business and Art in Music: Gazing Into the Star Texts of Michelle Branch and Regina Spektor Max Neibaur University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2015 Balancing Business and Art in Music: Gazing into the Star Texts of Michelle Branch and Regina Spektor Max Neibaur University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Neibaur, Max, "Balancing Business and Art in Music: Gazing into the Star Texts of Michelle Branch and Regina Spektor" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 823. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BALANCING BUSINESS AND ART IN MUSIC: GAZING INTO THE STAR TEXTS OF MICHELLE BRANCH AND REGINA SPEKTOR by Max Neibaur A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2015 ABSTRACT BALANCING BUSINESS AND ART IN MUSIC: GAZING INT O THE STAR TEXTS OF MICHELLE BRANCH AND REGINA SPEKTOR by Max Neibaur The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman This research builds on literature presenting ideas on the tension between business and art in the music industry and literature defining what a star is by analyzing star texts. Specifically, it looks at how business and art is balanced in the star texts of Michelle Branch and Regina Spektor and what tension this balancing creates. -

Press and Sustain Identity, to Transmit Lessons Across Generations and to Bridge Cultural Divides and Connect Us All on a Universal Level

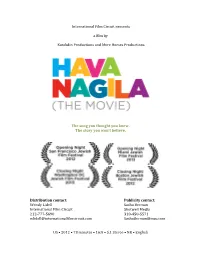

International Film Circuit presents a film by Katahdin Productions and More Horses Productions The song you thought you knew. The story you won’t believe. Distribution contact: Publicity contact: Wendy Lidell Sasha Berman International Film Circuit Shotwell Media 212-777-5690 310-450-5571 [email protected] [email protected] US • 2012 • 73 minutes • 16:9 • 5.1 Stereo • NR • English THE FILMMAKERS Directed and Produced by...........................................................................ROBERTA GROSSMAN Written and Produced by......................................................................................SOPHIE SARTAIN Produced by...........................................................................................................MARTA KAUFFMAN Executive Produced by..................................................................................................LISA THOMAS Cinematography by..............................................................DYANNA TAYLOR AND MIKE CHIN Edited by.....................................................................................................................CHRIS CALLISTER INTERVIEWS (in order of appearance) Johnny Yune Josh Kun Henry Sapoznik James Loeffler Chazzan Danny Maseng Rabbi Yisrael Friedman Rabbi Lawrence Kushner Dr. Gila Flam Edwin Seroussi Sheryl Shakinovsky, Devorah Lees and Naomi Kaplan Jay Starr, Deena Starr and Rachel Nathanson Ayala Goren Dani Dassa Leonard Nimoy Pete Sokolow Irving Fields Lila Corwin Berman Harry Belafonte Connie Francis -

2012 May 22 May 29

NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE STREET DATES: MAY 22 MAY 29 ISSUE 11 wea.com 2012 5/22/12 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ORDERS ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP QTY DUE Kimbra Vows WB CD 093624951346 530856 $13.99 5/2/12 The Dean Martin Variety Show Uncut Martin, Dean TL DV 610583431698 27108 $29.95 4/25/12 (3DVD) Last Update: 08/15/12 For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. ARTIST: Kimbra TITLE: Vows Label: WB/Warner Bros. Config & Selection #: CD 530856 Street Date: 05/22/12 Order Due Date: 05/02/12 UPC: 093624951346 OTHER EDITIONS Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 A 531998 Vinyl SRP: $13.99 ($18.98) Alphabetize Under: K TRACKS Compact Disc 1 01 Settle Down 08 Come Into My Head TOURS MORE 02 Something In The Way You Are 09 Sally I Can See You 03 Cameo Lover 10 Posse 10/12/12 04 Two Way Street 11 Home Verizon Theatre At Grand 05 Old Flame 12 The Build Up Prairie 06 Good Intent 13 Warrior (Bonus Track) Grand Prairie, TX 07 Plain Gold Ring (Live) 10/13/12 The Belmont Austin, TX 10/14/12 ALBUM FACTS Zilker Park Genre: Rock Producers: Mike Elizondo Radio Formats: Triple A, Alternative, Hot AC Packaging Specs: digi pak Austin, TX Focus Markets: New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, Washington DC, Minneapolis, Portland 10/16/12 Varsity Theater Vinyl Details: 1-LP, regular weight (150 gram) black vinyl at United in single-pocket jacket with printed dust sleeve at Minneapolis, MN Imprint. -

OLYMPIC 50 Musica Bohemica 5CD HITY / SINGLY / RARITY Písně a Tance Barokní Foto © Archiv Best I.A

TATA BOJS Reedice na MAX V+W Linkin Park Jiřímu Voskovcovi Living Things k narozeninám OLYMPIC 50 Musica Bohemica 5CD HITY / SINGLY / RARITY Písně a tance barokní Foto © archiv Best I.A. www.facebook.com/Supraphon ČERVEN 2012 PŘIPOMÍNÁME NOVINKY Z MINULÉ NABÍDKY DVD+CD SU 7123-9 Aneta Langerová Pár míst... ZÁZNAM AKUSTICKÉHO KONCERTU SE SMYČCOVÝM TRIEM BIO OKO, PRAHA Záznam dvou koncertů ze speciálního turné ukazuje, že i songy spíše baladicky zamyšlené Anety Langerové! Dlouholetý sen jedné dokáží udržet pozornost diváků po celých z našich nejoblíbenějších a nejoriginálnějších zaznamenaných 107 minut. Ty z nich vybrané zpěvaček/ skladatelek se konečně naplnil: stále dále výtečně fungují jako koncertní CD, tvořící pokračující šňůra vystoupení Pár míst spojila druhou část tohoto digipakového balení. její písničky se smyčcovým triem. Skladby Voda živá, Hříšná těla křídla motýlí, ale také DVD+CD z jejích tří alb tak získaly další, někdy intimnější, Dokola, Podzim, Jsem, Možná, Malá mořská jindy překvapivě ještě naléhavější rozměr. víla, Jedináček, Vzpomínka, Vysoké napětí, Sta- Aneta (zpěv, kytara, kalimba), Jakub Zitko čilo říct a dalších šest písniček na DVD, navíc KATEGORIE: FLTS2 (klavír, kytara, zpěv), Veronika Vališová (housle, z televizního záznamu proměněných v audio DOPORUČENÁ MOC: DVD+CD 449,- Kč zpěv), Vladan Malinjak (viola, zpěv) a Dorota podobu, jsou důkazem jedinečné kvality i atrak- VYCHÁZÍ: JIŽ VYŠLO Barová (violoncello, zpěv) zahráli také dva tivity Anety s přáteli. Krásný dárek fanouškům koncerty v pražském Bio Oko. Výborné aranže i vzpomínka na prezidenta Havla, jemuž byly byly doplněny promyšlenými pódiovými tyto dva koncerty v prosinci 2011 věnovány. projekcemi, takže obrazové zdokumentování bylo opravdu namístě.