Moving the Margins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Program Book

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN GHALLL OHF FAFME 2009 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Dana V. Starks Mayor Chairman and Commissioner Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues William W. Greaves, Ph.D. Director/Community Liaison COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, Suite 300 Chicago, Illinois 60654-3478 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) © 2009 Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame In Memoriam Robert Maddox Tony Midnite 2 3 4 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (now the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, their organizations and their friends, as well as their contributions to the LGBT communities and to the city of Chicago. -

Books for Kids with LGBT Parents These Books Specifically Depict Our Families, Either in the Story, in the Illustrations, Or with Photographs

Books for kids with LGBT parents These books specifically depict our families, either in the story, in the illustrations, or with photographs. All titles can be ordered online at www.familypride.org. Books for Children Ages 2-6 123 A Family Counting Book Bobbie Combs 8.95 paperback Ages 3-6 Have fun with the kids, moms, dads and pets in this delightful book that celebrates our families a it teaches young children to count from one to twenty. ABC A Family Alphabet Book Bobbie Combs 8.95 paperback Ages 3-6 Have fun with the kids, moms, dads and pets in this delightful book that celebrates our families a it teaches young children the alphabet. Bedtime for Baby Teddy T.Arc-Dekker 12.95 paperback Ages 0-3 This Australian import is a bit pricey at only 12 pages (stiffer than paper, but not as hard as a board book), but it's by far the easiest story we've seen that features two mommies, with soft, full-color illustrations that show two "Mummy Teddies" spending time with their little one. Asha's Mums Rosamund Elwin 6.95 paperback Ages 3-6 This Canadian book tells the story of Asha, whose classmates find out that she has two mums when she needs to get a field trip permission slip filled out. Several lively discussions with her classmates later, Asha feels great about her two mums and so do her friends. Heather Has Two Mommies Lesl_a Newman 10.95 paperback Ages 3-6 The first book to portray lesbian families in a positive way has been updated and edited from the original; the text is shorter, making the book more focused on the message that ""the most important thing about a family is that all the people in it love each other." Felicia's Favorite Story Lesl_a Newman 9.95 paperback Ages 2 & up It's bedtime, but before Felicia goes to sleep she wants to hear her favorite story, the story of how she was adopted by Mama Linda and Mama Nessa. -

Human Adventure by Valen Eberhard Staffwriter

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 10-10-2005 The Knight Volume 16: Issue 6 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The Knight Volume 16: Issue 6" (2005). The Current. 575. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/575 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. H K' I H NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 10, 2005 HTTP:/ /WWW.KNIGHTNEWSONLINE.COM VOLUME 16, ISSUE 6 Interdisciplinclry Arts Presents The Human Adventure By Valen Eberhard StaffWriter On October 14, The Human Adventure opens with a free preview for NSU students at 7:30 p.m in the Rose & Alfred Miniaci Center. The following night marks the opening of the musical production for the general public. The story llne takes Joseph Campbell's A Hero's journey and combines his philosophy of past heroes ancient myths with those if modern day heroes. Throughout the duration of the program, ancient myths will presented to . the publlc in a more modern light with an exaggerated social and psychological problems. A lor has gone into the planning of the production, which was put together by Cassie Allen, EvettNavano, andMelissaAxel, with the support of the Interdisciplinary Arts Program. Auditions were originally set for August 24 and 25, but hurricane Katrina put a hold on the second day of auditions. -

Race, Sexuality, and Masculinity on the Down Low

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 Race, Sexuality, and Masculinity on the Down Low Stephen Kochenash The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2496 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RACE, SEXUALITY, & MASCULINITY ON THE DOWN LOW by STEPHEN KOCHENASH A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 STEPHEN KOCHENASH All Rights Reserved ii RACE, SEXUALITY, & MASCULINITY ON THE DOWN LOW by Stephen Kochenash This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________ ________________________________________________ Date James Wilson Thesis Advisor ___________________ ________________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT RACE, SEXUALITY, & MASCULINITY ON THE DOWN LOW by Stephen Kochenash Advisor: Dr. James Wilson In a so-called post-racial America, a new gay identity has flourished and come into the limelight. However, in recent years, researchers have concluded that not all men who have sex with other men (MSM) self-identify as gay, most noticeably a large population of Black men. -

Getting Down to Basics: Tools to Support LGBTQ Youth in Care, Child Welfare League a Place of Respect: a Guide for Group Care of Am

Getting Down to Basics Tools to Support LGBTQ Youth in Care Overview of Tool Kit Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) young people are in America’s child welfare and juvenile justice systems in disproportionate numbers. Like all young people in care, they have the right to be safe and protected. All too often, however, they are misunderstood and mistreated, leading to an increased risk of negative outcomes. This tool kit offers practical tips and information to ensure that LGBTQ young people in care receive the support and services they deserve. Developed in partnership by the Child Welfare League of America (CWLA) and Lambda Legal, the tool kit gives guidance on an array of issues affecting LGBTQ youth and the adults and organizations who provide them with out-of-home care. TOPICS INCLUDED IN THIS TOOL KIT 3 Basic Facts About Being LGBTQ 5 Information for LGBTQ Youth in Care 7 Families Supporting an LGBTQ Child FOSTERING TRANSITIONS 9 Caseworkers with LGBTQ Clients A CWLA/Lambda Legal 11 Foster Parents Caring for LGBTQ Youth Joint Initiative 13 Congregate Care Providers Working with LGBTQ Youth 15 Attorneys, Guardians ad Litem & Advocates Representing LGBTQ Youth 17 Working with Transgender Youth 21 Keeping LGBTQ Youth Safe in Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Placements 23 Working with Homeless LGBTQ Youth 25 Faith-Based Providers Working with LGBTQ Youth 27 Basic LGBTQ Policies, Training & Services for Child Welfare Agencies 29 Recommendations for Training & Education on LGBTQ Issues 31 What the Experts Say: Position & Policy Statements on LGBTQ Issues from Leading Professional Associations 35 LGBTQ Youth Resources 39 Teaching LGBTQ Competence in Schools of Social Work 41 Combating Misguided Efforts to Ban Lesbian & Gay Adults as Foster & Adoptive Parents 45 LGBTQ Youth Risk Data 47 Selected Bibliography CHILD WELFARE LEAGUE OF AMERICA CWLA is the nation’s oldest and largest nonprofit advocate for children and youth and has a membership of nearly 1000 public and private agencies, including nearly every state child welfare system. -

University Theatre Will Present Irish Classic 'Playboy of the Western

F R O S T B U R G S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y StateLineswwwfrostburgedu/news/statelineshtm For and about FSU people A publication of the FSU Office of Advancement Volume 36, Number 20, February 27, 2006 Copy deadline: noon Wednesday, 228 Hitchins or emedcalf@frostburg$edu University Theatre Will Present Irish Classic ‘Playboy of the Western World’ University Theatre will present J.M. village girls and Widow Quinn. He also Synge’s Irish classic, “The Playboy of the wins the affections of the strong-willed Western World” on March 3, 4, 9, 10 and Pegeen Mike who runs her father’s pub 11 at 8 p.m., and March 4 at 2 p.m., in where Christy has taken refuge. How- the Performing Arts Center Drama ever, when another stranger comes to Theatre. town, Christy’s image takes a turn for When Christy Mahon saunters into a the worse, causing townsfolk to reveal small Irish town claiming to have killed some harsh realities that underlie their his father in self-defense, the villagers isolated community. become captivated by his mystique and Tickets are $5 for students and $10 bravery, proclaiming him, “Playboy of for the general public. For reservations, the Western World.” Their praise gives call the University Theatre box office at Christy newfound confidence and he x7462, Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. Nate Kurtz and Justine Poulin quickly becomes a favorite among the to 4 p.m. Lane University Center’s Alice R. Manicur America’s music of the first half of the Presentations Assembly Hall. -

Living on the Down-Low: Stories

LIVING ON THE DOWN-LOW: STORIES FROM AFRICAN AMERICAN MEN by PRISCILLA GANN WILSON A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Counselor Education in the Graduate School of the University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Priscilla Gann Wilson 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This study examined the lived experiences of African American men who publicly identified as heterosexual, but privately engaged in intimate relationships with other men. These men are identified by several terminologies including Down Low (DL) and men who have sex with men (MSM). Seven men participated in the study which consisted of three audiotaped phone interviews over the course of three months. One of the participants withdrew from the study before his last interview. The participants identified themselves as being African American, over the age of 19, and having lived, or are currently living, on the DL. The participants were interviewed about their experiences including family of origin beliefs about people who were gay, influences in the African American community that shaped their sexual identity construction, their lives on the DL, mental health issues that they may have experienced, and disclosure and non-disclosure of their sexual identity. Phenomenological research methods were used to collect and analyze and data along with the theoretical methodological framework of Critical Race Theory (CRT), which was used as a tool to identify how factors of race, gender, and sexuality play roles in the construction of African American DL and MSM. QSR NVIVO qualitative research software was also used to code categories and identify relationships that resulted from coding the transcripts. -

2016 Program Book

2016 INDUCTION CEREMONY Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame Gary G. Chichester Mary F. Morten Co-Chairperson Co-Chairperson Israel Wright Executive Director In Partnership with the CITY OF CHICAGO • COMMISSION ON HUMAN RELATIONS Rahm Emanuel Mona Noriega Mayor Chairman and Commissioner COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST Published by Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame 3712 North Broadway, #637 Chicago, Illinois 60613-4235 773-281-5095 [email protected] ©2016 Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame In Memoriam The Reverend Gregory R. Dell Katherine “Kit” Duffy Adrienne J. Goodman Marie J. Kuda Mary D. Powers 2 3 4 CHICAGO LGBT HALL OF FAME The Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame (formerly the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame) is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, its Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (later the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame (changed to the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 2015) in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. Today, after the advisory council’s abolition and in partnership with the City, the Hall of Fame is in the custody of Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame, an Illinois not- for-profit corporation with a recognized charitable tax-deductible status under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3). -

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: a Historical Analysis Of

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Lance E. Poston December 2018 © 2018 Lance E. Poston. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia by LANCE E. POSTON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Katherine Jellison Professor of History Joseph Shields Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT POSTON, LANCE E., PH.D., December 2018, History Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia Director of Dissertation: Katherine Jellison This dissertation challenges the widespread myth that black Americans make up the most homophobic communities in the United States. After outlining the myth and illustrating that many Americans of all backgrounds had subscribed to this belief by the early 1990s, the project challenges the narrative of black homophobia by highlighting black urban neighborhoods in the first half of the twentieth century that permitted and even occasionally celebrated open displays of queerness. By the 1960s, however, the black communities that had hosted overt queerness were no longer recognizable, as the public balls, private parties, and other spaces where same-sex contacts took place were driven underground. This shift resulted from the rise of the black Civil Rights Movement, whose middle-class leadership – often comprised of ministers from the black church – rigorously promoted the respectability of the race. -

Basic Reforms to Address the Unmet Needs of Lgbt Foster Youth

II. BASIC REFORMS TO ADDRESS THE UNMET NEEDS OF LGBT FOSTER YOUTH What emerges from our state-by-state survey is a picture of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth under-served by foster care systems. These youth remain in the margins, their best interests ignored and their safety in jeopardy. To remedy LGBT invisibility, prevent abuse, and improve care for these adolescents, we propose the following crucial, basic reforms in the areas of non-discrimination policies, training for foster parents and foster care staff,48 and LGBT youth services and programs. A. Non-discrimination policies States should adopt and enforce explicit, systemwide policies prohibiting discrimina- tion. Specifically, these should include prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of: the sexual orientation of foster care youth, the sexual orientation of foster parents and other foster household members, the sexual orientation of foster care staff, the HIV/AIDS status of foster care youth, the HIV/AIDS status of foster parents and other foster household members, and the HIV/AIDS status of foster care staff. These policies should encompass actual or perceived sexual orientation or HIV/ AIDS status. Discrimination prohibitions should also forbid discrimination on the basis of gender identity. Sex discrimination provisions should be interpreted to bar such discrimi- nation, and that scope can be made explicit by enumerating sex, including gender identity, among forbidden bases of discrimination in agency policies. Adopting LGBT non-discrimination policies is an important acknowledgment that LGBT youth are present in the foster care system in significant numbers and that they 22 Youth in the Margins often face prejudice, neglect, and abuse. -

The Trevor Project; and Truth Wins out in SUPPORT of APPELLEES to AFFIRM the ORDER DENYING a PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

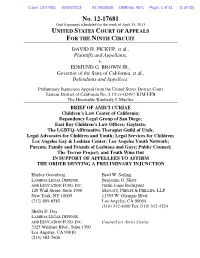

Case: 12-17681 02/06/2013 ID: 8503545 DktEntry: 60-1 Page: 1 of 41 (1 of 53) No. 12-17681 Oral Argument scheduled for the week of April 15, 2013 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DAVID H. PICKUP, et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants , v. EDMUND G. BROWN JR., Governor of the State of California, et al., Defendants and Appellees . Preliminary Injunction Appeal from the United States District Court Eastern District of California No. 2:12-cv-02497-KJM-EFB The Honorable Kimberly J. Mueller BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE Children’s Law Center of California; Dependency Legal Group of San Diego; East Bay Children’s Law Offices; Gaylesta; The LGBTQ-Affirmative Therapist Guild of Utah; Legal Advocates for Children and Youth; Legal Services for Children; Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center; Los Angeles Youth Network; Parents, Family and Friends of Lesbians and Gays; Public Counsel; The Trevor Project; and Truth Wins Out IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES TO AFFIRM THE ORDER DENYING A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Hayley Gorenberg Brad W. Seiling LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE Benjamin G. Shatz AND EDUCATION FUND , INC . Justin Jones Rodriguez 120 Wall Street, Suite 1900 MANATT , PHELPS & PHILLIPS , LLP New York, NY 10005 11355 W. Olympic Blvd. (212) 809-8585 Los Angeles, CA 90064 (310) 312-4000 Fax (310) 312-4224 Shelbi D. Day LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND , INC . Counsel for Amici Curiae 3325 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1300 Los Angeles, CA 90010 (213) 382-7600 Case: 12-17681 02/06/2013 ID: 8503545 DktEntry: 60-1 Page: 2 of 41 (2 of 53) CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT -

Download PDF Datastream

Claiming History, Claiming Rights: Queer Discourses of History and Politics By Evangelia Mazaris B.A., Vassar College, 1998 A.M., Brown University, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Evangelia Mazaris This dissertation by Evangelia Mazaris is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date: ________________ ______________________________ Ralph E. Rodriguez, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Karen Krahulik, Reader Date: ________________ ______________________________ Steven Lubar, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Evangelia Mazaris was born in Wilmington, Delaware on September 21, 1976. She received her B.A. in English from Vassar College in 1998. Mazaris completed her A.M. in Museum Studies/American Civilization at Brown University in 2005. Mazaris was a Jacob Javits Fellow through the United States Department of Education (2004 – 2009). Mazaris is the author of “Public Transgressions: the Reverend Phebe Hanaford and the „Minister‟s Wife‟,” published in the anthology Tribades, Tommies and Transgressives: Lesbian Histories, Volume I (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2008). She also published the article “Evidence of Things Not Seen: Greater Light as Faith Manifested,” in Historic Nantucket (Winter 2001). She has presented her work at numerous professional conferences, including the American Studies Association (2008), the New England American Studies Association (2007), the National Council on Public History (2009), and the University College Dublin‟s Historicizing the Lesbian Conference (2006).