Race, Sexuality, and Masculinity on the Down Low

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Adventure by Valen Eberhard Staffwriter

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 10-10-2005 The Knight Volume 16: Issue 6 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The Knight Volume 16: Issue 6" (2005). The Current. 575. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/575 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. H K' I H NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 10, 2005 HTTP:/ /WWW.KNIGHTNEWSONLINE.COM VOLUME 16, ISSUE 6 Interdisciplinclry Arts Presents The Human Adventure By Valen Eberhard StaffWriter On October 14, The Human Adventure opens with a free preview for NSU students at 7:30 p.m in the Rose & Alfred Miniaci Center. The following night marks the opening of the musical production for the general public. The story llne takes Joseph Campbell's A Hero's journey and combines his philosophy of past heroes ancient myths with those if modern day heroes. Throughout the duration of the program, ancient myths will presented to . the publlc in a more modern light with an exaggerated social and psychological problems. A lor has gone into the planning of the production, which was put together by Cassie Allen, EvettNavano, andMelissaAxel, with the support of the Interdisciplinary Arts Program. Auditions were originally set for August 24 and 25, but hurricane Katrina put a hold on the second day of auditions. -

University Theatre Will Present Irish Classic 'Playboy of the Western

F R O S T B U R G S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y StateLineswwwfrostburgedu/news/statelineshtm For and about FSU people A publication of the FSU Office of Advancement Volume 36, Number 20, February 27, 2006 Copy deadline: noon Wednesday, 228 Hitchins or emedcalf@frostburg$edu University Theatre Will Present Irish Classic ‘Playboy of the Western World’ University Theatre will present J.M. village girls and Widow Quinn. He also Synge’s Irish classic, “The Playboy of the wins the affections of the strong-willed Western World” on March 3, 4, 9, 10 and Pegeen Mike who runs her father’s pub 11 at 8 p.m., and March 4 at 2 p.m., in where Christy has taken refuge. How- the Performing Arts Center Drama ever, when another stranger comes to Theatre. town, Christy’s image takes a turn for When Christy Mahon saunters into a the worse, causing townsfolk to reveal small Irish town claiming to have killed some harsh realities that underlie their his father in self-defense, the villagers isolated community. become captivated by his mystique and Tickets are $5 for students and $10 bravery, proclaiming him, “Playboy of for the general public. For reservations, the Western World.” Their praise gives call the University Theatre box office at Christy newfound confidence and he x7462, Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. Nate Kurtz and Justine Poulin quickly becomes a favorite among the to 4 p.m. Lane University Center’s Alice R. Manicur America’s music of the first half of the Presentations Assembly Hall. -

Living on the Down-Low: Stories

LIVING ON THE DOWN-LOW: STORIES FROM AFRICAN AMERICAN MEN by PRISCILLA GANN WILSON A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Counselor Education in the Graduate School of the University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Priscilla Gann Wilson 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This study examined the lived experiences of African American men who publicly identified as heterosexual, but privately engaged in intimate relationships with other men. These men are identified by several terminologies including Down Low (DL) and men who have sex with men (MSM). Seven men participated in the study which consisted of three audiotaped phone interviews over the course of three months. One of the participants withdrew from the study before his last interview. The participants identified themselves as being African American, over the age of 19, and having lived, or are currently living, on the DL. The participants were interviewed about their experiences including family of origin beliefs about people who were gay, influences in the African American community that shaped their sexual identity construction, their lives on the DL, mental health issues that they may have experienced, and disclosure and non-disclosure of their sexual identity. Phenomenological research methods were used to collect and analyze and data along with the theoretical methodological framework of Critical Race Theory (CRT), which was used as a tool to identify how factors of race, gender, and sexuality play roles in the construction of African American DL and MSM. QSR NVIVO qualitative research software was also used to code categories and identify relationships that resulted from coding the transcripts. -

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: a Historical Analysis Of

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Lance E. Poston December 2018 © 2018 Lance E. Poston. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia by LANCE E. POSTON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Katherine Jellison Professor of History Joseph Shields Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT POSTON, LANCE E., PH.D., December 2018, History Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia Director of Dissertation: Katherine Jellison This dissertation challenges the widespread myth that black Americans make up the most homophobic communities in the United States. After outlining the myth and illustrating that many Americans of all backgrounds had subscribed to this belief by the early 1990s, the project challenges the narrative of black homophobia by highlighting black urban neighborhoods in the first half of the twentieth century that permitted and even occasionally celebrated open displays of queerness. By the 1960s, however, the black communities that had hosted overt queerness were no longer recognizable, as the public balls, private parties, and other spaces where same-sex contacts took place were driven underground. This shift resulted from the rise of the black Civil Rights Movement, whose middle-class leadership – often comprised of ministers from the black church – rigorously promoted the respectability of the race. -

Download PDF Datastream

Claiming History, Claiming Rights: Queer Discourses of History and Politics By Evangelia Mazaris B.A., Vassar College, 1998 A.M., Brown University, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Evangelia Mazaris This dissertation by Evangelia Mazaris is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date: ________________ ______________________________ Ralph E. Rodriguez, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Karen Krahulik, Reader Date: ________________ ______________________________ Steven Lubar, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Evangelia Mazaris was born in Wilmington, Delaware on September 21, 1976. She received her B.A. in English from Vassar College in 1998. Mazaris completed her A.M. in Museum Studies/American Civilization at Brown University in 2005. Mazaris was a Jacob Javits Fellow through the United States Department of Education (2004 – 2009). Mazaris is the author of “Public Transgressions: the Reverend Phebe Hanaford and the „Minister‟s Wife‟,” published in the anthology Tribades, Tommies and Transgressives: Lesbian Histories, Volume I (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2008). She also published the article “Evidence of Things Not Seen: Greater Light as Faith Manifested,” in Historic Nantucket (Winter 2001). She has presented her work at numerous professional conferences, including the American Studies Association (2008), the New England American Studies Association (2007), the National Council on Public History (2009), and the University College Dublin‟s Historicizing the Lesbian Conference (2006). -

FM-Schutt 6E-45771

CHAPTER 8 Intersectionalities udre Lorde is known for describing herself as “Black, lesbian, feminist, mother, warrior, poet.” For Lorde, these markers interacted and affected Aher life simultaneously. Today, feminists, other activists, and those involved in the professions of law and social work use the term intersectionality to describe our complex awareness that we inhabit—and are inhabited by—multiple categories of identity and that our experi - ence of several identities taken together may be emotionally, culturally, and materi - ally different than the experience of any one particular identity category by itself. A white gay man, for instance, might feel oppressed by society’s negative attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people at the same time that he enjoys privilege connected to being a white man. Conversely, a black gay man may experience his queerness not only as a gay man but as a black man; that is, he nego - tiates two minoritized categories in U.S. culture. His experience, however, is not nec - essarily one of just “doubled” oppression; rather, he may experience both a dominant culture and an African American culture that code “gayness” as a white phenomenon, so his queerness may be invisible to many in his differ ent communities. His experi - ence of himself as a “black gay man” assumes com plexities and nuances that are intrinsic to how this culture understands and constructs both race and sexuality. At the same time, intersectionality also allows us to see not only how multiple identities complicate our lives but also how the very aspects of our identity that are sources of oppression in one environment serve as sources of privilege in another. -

Introduction

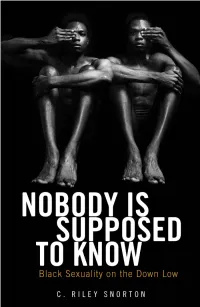

Introduction Transpositions T e myth of our potent sexuality has been, I would argue, not only a great burden but also one of the most potent means by which we have resisted — or at least adapted — racist and racialist oppression. — Robert Reid- Pharr, Once You Go Black Myth is neither a lie nor a confession: it is an inf exion. — Roland Barthes, Mythologies On April 16, 2004, Oprah Winfrey began her episode “A Secret Sex World: Living on the ‘Down Low’ ” with an unusual announcement: “I’m an Afri- can American woman.” Her studio audience responded with laughter. Realizing, perhaps, that her show opener had not elicited the intended re- action, Winfrey explained that the producers of T e Oprah Winfrey Show had had a similarly skeptical, perhaps even dismissive, response when she discussed her choice to open with a declaration of her identity: When I told the producers I wanted to say that, they go like, “Really now?” But I’m an African- American woman, so when I picked up the paper the other day and saw this headline, it really got my attention. T e headline says, “AIDS is the leading cause of death for African- Americans between the age of 25 and 44.” T at is startling! All my alarms went of . Not only are more Black people getting AIDS in record numbers . more women, listen to me now, more women, more college students and people over 50 are at greater risk than ever before. Today, you’re gonna hear many reasons why AIDS is on the rise again. -

Volcanoes & Other Yards

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Theses Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Winter 12-11-2020 Volcanoes & Other Yards Rebeca Flores [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Rebeca, "Volcanoes & Other Yards" (2020). Master's Theses. 1339. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1339 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volcanoes & Other Yards Rebeca Flores © 2020 Let us gather in a flourishing way en la luz y en la carne of our heart to toil tranquilo in fields of blossoms juntos to stretch los brazos tranquilos with the rain en la mañana temprana estrella on our forehead cielo de calor and wisdom to meet us where we toil siempre in the garden of our struggle and joy Juan Felipe Herrera My Pops said, “I needed a job.” I thought I believed him. Kendrick Lamar Contents Abstract i Preface ii Yo! There’s a Volcano in The Backyard 1 My Country Gassed Children 17 Warehouse Party 20 Roadside Memorial 32 The Drive Thru and The Taco Truck 49 The Uninvited Guest 52 Pungency 64 Zapatos/Shoes 68 Uprooted 70 Everyday Going into a Pharmacy 84 Workers 87 Welfare Line 99 The Flyer 107 When You Come to Your Resting Place 118 i Abstract Volcanoes & Other Yards is a collection of short stories set in the yards of California, Mexico, and El Salvador. -

The Down Low and the Sexuality of Race Brad Elliott Stone, Loyola Marymount University

Brad Elliott Stone 2011 ISSN: 1832-5203 Foucault Studies, No. 12, pp. 36-50, October 2011 ARTICLE The Down Low and the Sexuality of Race Brad Elliott Stone, Loyola Marymount University ABSTRACT: There has been much interest in the phenomenon called ‚the Down Low,‛ in which ‚otherwise heterosexual‛ African American men have sex with other black men. This essay explores the biopolitics at play in the media’s curiosity about the Down Low. The Down Low serves as a critical, transgressive heterotopia that reveals the codetermi- nation of racism, sexism, and heterosexism in black male sexuality. Keywords: Foucault, race, sexuality, biopolitics. In this essay I offer a Foucauldian interpretation of the phenomenon in African American culture referred to as ‚the Down Low.‛ The cleanest definition of the Down Low is that it is a social scene in which otherwise heterosexual black men have sex with other men (usually also otherwise heterosexual black men). This scene came to the fore when it was (erro- neously) connected at the beginning of the millennium to an alleged increase in HIV infection rates in African American women, the supposed ‚unaware‛ heterosexual partners of Down Low men. Although the connection turns out to be unfounded, the forces of power at play in the discussion of the Down Low have real racist, sexist, and heterosexist effects in African Americans. Any black sexual politics must keep these effects on the for- mation of African American identities in mind. Of use for such mindfulness are Foucault’s philosophical methods. Foucault’s ac- count of sexuality and race offers black sexual politics helpful tools for cutting past tradition and seeing the workings of power relations that created not only racial identities but genders and sexual orientation. -

Surviving Racist Culture: Strategies of Managing Racism

SURVIVING RACIST CULTURE: STRATEGIES OF MANAGING RACISM AMONG GAY MEN OF COLOUR—AN INTERPRETATIVE PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS SULAIMON GIWA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN SOCIAL WORK YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO November 2016 © Sulaimon Giwa, 2016 Abstract Racism, a unique source of stress, occupies a peripheral point of analysis in the literature on gay, lesbian, and bisexual (GLB) health research. Canadian investigators have not examined the coping strategies that non-White gay men use. Lacking knowledge of the group’s coping responses overlooks the dynamics of resistance and prevents interventions for addressing racism from being developed. The current study’s aims were to explore the contexts in which gay men of colour experienced gay-specific racism; to investigate their understanding of factors contributing to the experience of racism; and to examine strategies they used to manage the stress of racism. Foregrounding issues of White supremacy and racial oppression, the study used frameworks from critical race and queer theories and minority stress theory, integrating insights from the psychological model of stress and coping. Data were collected in Ottawa, Canada, employing focus groups and in-depth interviews with 13 gay men who identified as Black, East Asian, South Asian, and Arab/Middle Eastern. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), the study concluded that racism was pervasive in Ottawa’s GLB community, at individual, institutional, and cultural levels. Racial-cultural socialization processes were found to influence racist attitudes and practices. Racism’s subtle, insidious forms undermined discrimination claims by gay men of colour, in that White gay men denied any racist attitudes and actions. -

Glimpses of Dark Money

--Discussion Draft--Not for citation-- What do Corporations Have to Hide? Glimpses of Dark Money May 31, 2016 Ciara Torres-Spelliscy Introduction Playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda told the graduates of the University of Pennsylvania, “[e]very story you choose to tell, by necessity, omits others from the larger narrative.”1 This is true. But American elections are missing a key part of the story: exactly who is funding political ads. Between 2010 and 2014, there was $600 million of dark money spent in federal elections alone. But now that corporate money is allowed in politics through perfectly legal independent expenditures, the open question remains, why is corporate money going dark? Post-Citizens United, the press has shown a renewed interest in hidden corporate political spending.2 They have reported on inadvertent and court ordered disclosures by corporations. These reports provide an admittedly limited glimpse into what corporations are doing on the down low and allows us to start to explore what exactly are corporate political spenders hiding and why. Because of the brevity of this piece a definitive account of all that is hidden in the realm of corporate political spending is not possible. But this piece can offer a starting point for both discussion and further research. Defining the Modern Dark Money Problem Here “dark money” does not refer to the excellent book by Jane Mayer of the same title, but rather, it refers to untraceable political spending.3 Dark money is money that has been routed through an opaque nonprofit — thus concealing its true source from voters and investors alike. -

Racing the Closet, Jsp 2010

russell K. robinson Professor of Law Russell k. Robinson graduated with honors from harvard Law School (1998) after receiving his B.A., summa cum laude, from hampton University (1995). he clerked for Judge Dorothy Nelson of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (1998-99) and for Justice Stephen Breyer of the U.S. Supreme Court (2000-01). he has also worked for the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legal Counsel (1999-2000) and the firm of Akin, Gump, Strauss, hauer and Feld in Los Angeles, practicing entertainment law (2001-02). he was a visiting professor at Fordham Law School (2003-04). Professor Robinson’s current scholarly and teaching interests include antidiscrimination law, law and psychology, race and sexuality, constitutional law and media and entertainment law. his publications include: Casting and Caste-ing: Reconciling Artistic Freedom and Antidiscrimination Norms, 95 Cal L. Rev. 1 (2007); Uncovering Covering, 101 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1809 (2007); Perceptual Segregation, 108 Colum. L. Rev. 1093 (2008); Structural Dimensions of Romantic Preferences, 76 Fordham L. Rev. 2787 (2008); and Racing the Closet, 61 Stan. L. Rev. 1463 (2009). He is also working on an article regarding the legal regulation of sexuality in prison. 211617_SP_Text_r3.indd 45 8/19/2010 11:51:35 AM RACING the CLOSet* Russell k. Robinson** INTRODUCTIon ecently, the media have brought to light examples of ordinary black rmen who are said to live on the “down low” (or DL) in that they have primary romantic relationships with women while engaging in secret sex with men.1 A central theme of this media coverage, which I will call “DL discourse,” is that DL men expose their unwitting female partners to hIV, which stems from their secret sex with men.2 DL discourse warrants examination because it sits at the intersection of three important civil rights movements: (1) the gay rights movement, (2) the black anti-racist movement, and (3) AIDS activism.