Decoding Literary AIDS: a Study on Issues of the Body, Masculinity, and Self Identity in U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dining with Anna and Friends

Dining with Anna and Friends This list of restaurants, bars, delis, and food stores are related in one way or another to The Tales of the City (books and/or films) as well as to The Night Listener. They are grouped by neighborhoods or areas in San Francisco. Some have already been included in existing walking tours. More will be included in future tours. Many establishments – particularly bars and clubs – featured in Armistead Maupin’s books have since closed. The buildings were either vacant or have been converted into other types of businesses altogether (for example, one has been turned into a service for individuals who are homeless) at the time this list was created. For these reasons, those establishments have not been included in this list. As with the rest of the content of the Tours of the Tales website, this list will be periodically updated. If you have updates, please forward them to me. I appreciate your help. NOTE: Please do not consider this list an exhaustive list of eating/drinking establishments in San Francisco. For example, although there are several restaurants listed in “North Beach” below, there are many more excellent places in North Beach in addition to those listed. Also, do not consider this list an endorsement of any place included in the list. The Google map for this list of eating establishments: Dining with Anna and Friends. Aquatic Park/Fisherman’s Wharf/and the Embarcadero The Buena Vista Bar, 2765 Hyde Street (southwest corner of Hyde and Beach; across the street from the Powell-Hyde cable car turntable): Mary Ann Singleton was twenty-five years old when she saw San Francisco for the first time. -

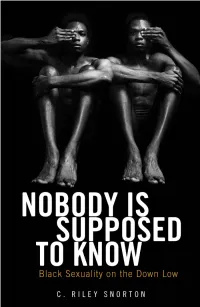

Race, Sexuality, and Masculinity on the Down Low

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 Race, Sexuality, and Masculinity on the Down Low Stephen Kochenash The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2496 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RACE, SEXUALITY, & MASCULINITY ON THE DOWN LOW by STEPHEN KOCHENASH A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 STEPHEN KOCHENASH All Rights Reserved ii RACE, SEXUALITY, & MASCULINITY ON THE DOWN LOW by Stephen Kochenash This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________ ________________________________________________ Date James Wilson Thesis Advisor ___________________ ________________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT RACE, SEXUALITY, & MASCULINITY ON THE DOWN LOW by Stephen Kochenash Advisor: Dr. James Wilson In a so-called post-racial America, a new gay identity has flourished and come into the limelight. However, in recent years, researchers have concluded that not all men who have sex with other men (MSM) self-identify as gay, most noticeably a large population of Black men. -

Living on the Down-Low: Stories

LIVING ON THE DOWN-LOW: STORIES FROM AFRICAN AMERICAN MEN by PRISCILLA GANN WILSON A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Counselor Education in the Graduate School of the University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Priscilla Gann Wilson 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This study examined the lived experiences of African American men who publicly identified as heterosexual, but privately engaged in intimate relationships with other men. These men are identified by several terminologies including Down Low (DL) and men who have sex with men (MSM). Seven men participated in the study which consisted of three audiotaped phone interviews over the course of three months. One of the participants withdrew from the study before his last interview. The participants identified themselves as being African American, over the age of 19, and having lived, or are currently living, on the DL. The participants were interviewed about their experiences including family of origin beliefs about people who were gay, influences in the African American community that shaped their sexual identity construction, their lives on the DL, mental health issues that they may have experienced, and disclosure and non-disclosure of their sexual identity. Phenomenological research methods were used to collect and analyze and data along with the theoretical methodological framework of Critical Race Theory (CRT), which was used as a tool to identify how factors of race, gender, and sexuality play roles in the construction of African American DL and MSM. QSR NVIVO qualitative research software was also used to code categories and identify relationships that resulted from coding the transcripts. -

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: a Historical Analysis Of

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Lance E. Poston December 2018 © 2018 Lance E. Poston. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia by LANCE E. POSTON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Katherine Jellison Professor of History Joseph Shields Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT POSTON, LANCE E., PH.D., December 2018, History Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia Director of Dissertation: Katherine Jellison This dissertation challenges the widespread myth that black Americans make up the most homophobic communities in the United States. After outlining the myth and illustrating that many Americans of all backgrounds had subscribed to this belief by the early 1990s, the project challenges the narrative of black homophobia by highlighting black urban neighborhoods in the first half of the twentieth century that permitted and even occasionally celebrated open displays of queerness. By the 1960s, however, the black communities that had hosted overt queerness were no longer recognizable, as the public balls, private parties, and other spaces where same-sex contacts took place were driven underground. This shift resulted from the rise of the black Civil Rights Movement, whose middle-class leadership – often comprised of ministers from the black church – rigorously promoted the respectability of the race. -

Download PDF Datastream

Claiming History, Claiming Rights: Queer Discourses of History and Politics By Evangelia Mazaris B.A., Vassar College, 1998 A.M., Brown University, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Evangelia Mazaris This dissertation by Evangelia Mazaris is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date: ________________ ______________________________ Ralph E. Rodriguez, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Karen Krahulik, Reader Date: ________________ ______________________________ Steven Lubar, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Evangelia Mazaris was born in Wilmington, Delaware on September 21, 1976. She received her B.A. in English from Vassar College in 1998. Mazaris completed her A.M. in Museum Studies/American Civilization at Brown University in 2005. Mazaris was a Jacob Javits Fellow through the United States Department of Education (2004 – 2009). Mazaris is the author of “Public Transgressions: the Reverend Phebe Hanaford and the „Minister‟s Wife‟,” published in the anthology Tribades, Tommies and Transgressives: Lesbian Histories, Volume I (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2008). She also published the article “Evidence of Things Not Seen: Greater Light as Faith Manifested,” in Historic Nantucket (Winter 2001). She has presented her work at numerous professional conferences, including the American Studies Association (2008), the New England American Studies Association (2007), the National Council on Public History (2009), and the University College Dublin‟s Historicizing the Lesbian Conference (2006). -

South Park: (Des)Construção Iconoclasta Das Celebridades

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica ÉRICO FERNANDO DE OLIVEIRA South Park: (des)construção iconoclasta das celebridades São Paulo Agosto de 2012 2 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica ÉRICO FERNANDO DE OLIVEIRA South Park: (des)construção iconoclasta das celebridades Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica da PUC-SP Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Luis Aidar Prado São Paulo Agosto de 2012 3 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica ÉRICO FERNANDO DE OLIVEIRA South Park: (des)construção iconoclasta das celebridades Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica da PUC-SP Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Luis Aidar Prado Comissão examinadora: __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ São Paulo Agosto de 2012 4 AGRADECIMENTOS À CAPES, pelo financiamento parcial da pesquisa. Ao Prof. Dr. José Luis Aidar Prado pela paciência e disponibilidade. Aos meus pais, irmãos e amigos, pela compreensão diante de minhas recusas. Aos meus colegas de curso, em especial, André Campos de Carvalho, Cynthia Menezes Mello e Fabíola Corbucci, Pela amizade e inestimável incentivo. Aos professores integrantes das bancas de qualificação e defesa, pelas orientações e disponibilidade. À Celina de Campos Horvat, por todos os motivos descritos acima. Toda piada é uma pequena revolução. (George Orwell) 5 Resumo O intuito desta pesquisa é estudar a construção social contemporânea das celebridades, bem como o papel que ela exerce na civilização midiática. -

1 NCLC 475: AIDS and Culture (4 Credits) New Century College

NCLC 475: AIDS and Culture (4 credits) New Century College, Spring 2011 Friday 10:30 AM – 1:15 PM(Robinson Room A 105) Michael Lecker, Instructor [email protected] / Enterprise Hall 416B Office hours: By appointment “My sweet brother…my brothers who have been my tender one for so many years, are falling down”- Aaron Shurin Course Description: This course will examine HIV/AIDS and its intersections with politics, culture, government, medicine, education, and commerce. As just illustrated, this epidemic has left little untouched. This course will examine how the impact and reaction to the epidemic. Required Texts (Available at the bookstore): Bordowitz, Gregg. The AIDS Crisis Is Ridiculous and Other Writings, 1986-2003. The MIT Press, 2006. Print. Monette, Paul. Borrowed Time: An AIDS Memoir. Mariner Books, 1998. Print. Pisani, Elizabeth. The Wisdom of Whores: Bureaucrats, Brothels and the Business of AIDS. W. W. Norton & Company, 2009. Print. Treichler, Paula A. How to Have Theory in an Epidemic: Cultural Chronicles of AIDS. 1st ed. Duke University Press, 1999. Print. ALL OTHER READING MATERIAL IS ON BB Course Assessment: Participation----------20% Hide/Seek------------ 5% Reading Responses--15% Proposal---------------10% Website----------------25% Commenting----------10% Written Exam---------15% Assignment Descriptions: Participation: 20 % Participation will be graded on several criteria. First, you must show up to participate. Second, you must bring the PRINTED reading materials for the day. And lastly, you must contribute positively to class discussions. Hide/Seek: 5% Choose one piece from the AIDS section of the Hide/Seek exhibit at the Portrait Gallery. Describe to me what you see and then tell me the significance. -

Pro Gradu Paronen

APPRAISAL IN ONLINE REVIEWS OF SOUTH PARK: A study of engagement resources used in online reviews. Master's thesis Tiina Paronen University of Jyväskylä Department of languages English August 2011 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Kielten laitos Tekijä – Author Tiina Paronen Työn nimi – Title APPRAISAL IN ONLINE REVIEWS OF SOUTH PARK: A study of engagement resources used in online reviews. Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level englanti Pro gradu -tutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages elokuu 2011 76 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Tutkielman tarkoituksena on selvittää, millaisin kielellisin keinoin kirjoittaja voi ilmaista mielipiteitään ja arvioitaan verkkoarvosteluissa. Tutkielma pyrkii kuvailemaan keinoja, joilla kirjoittaja huomioi lukijan pyrkiessään omiin tavoitteisiinsa. Tutkielman tarkoituksena on myös tarkastella verkkoarvosteluja genre-analyysin näkökulmasta. Teoreettisesti ja metodologisesti tutkimus nojaa Martinin ja Whiten kehittelemään arvioimisen analyysiin (appraisal analysis). Tutkimusaineisto koostuu neljästätoista televisioanimaation verkkoarvostelusta. Verkkoarvosteluja tarkastellaan laadullisesti. Tutkimuksen tulokset osoittavat kirjoittajan kiinnittävän paljon huomiota suhteeseen lukijan kanssa, mikä ilmenee kirjoittajan käyttämistä kielellisistä keinoista. Tutkimuksen perusteella lukijan ja kirjoittajan suhde on kirjoittajalle vähintään yhtä tärkeää kuin kirjoittajan omien mielipiteiden ilmaisu. Tutkimuksen tulokset osoittavat, että kirjailija luo itselleen -

Introduction

Introduction Transpositions T e myth of our potent sexuality has been, I would argue, not only a great burden but also one of the most potent means by which we have resisted — or at least adapted — racist and racialist oppression. — Robert Reid- Pharr, Once You Go Black Myth is neither a lie nor a confession: it is an inf exion. — Roland Barthes, Mythologies On April 16, 2004, Oprah Winfrey began her episode “A Secret Sex World: Living on the ‘Down Low’ ” with an unusual announcement: “I’m an Afri- can American woman.” Her studio audience responded with laughter. Realizing, perhaps, that her show opener had not elicited the intended re- action, Winfrey explained that the producers of T e Oprah Winfrey Show had had a similarly skeptical, perhaps even dismissive, response when she discussed her choice to open with a declaration of her identity: When I told the producers I wanted to say that, they go like, “Really now?” But I’m an African- American woman, so when I picked up the paper the other day and saw this headline, it really got my attention. T e headline says, “AIDS is the leading cause of death for African- Americans between the age of 25 and 44.” T at is startling! All my alarms went of . Not only are more Black people getting AIDS in record numbers . more women, listen to me now, more women, more college students and people over 50 are at greater risk than ever before. Today, you’re gonna hear many reasons why AIDS is on the rise again. -

Gruda Mpp Me Assis.Pdf

MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK ASSIS 2011 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo Trabalho financiado pela CAPES ASSIS 2011 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Gruda, Mateus Pranzetti Paul G885d O discurso politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park / Mateus Pranzetti Paul Gruda. Assis, 2011 127 f. : il. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo. 1. Humor, sátira, etc. 2. Desenho animado. 3. Psicologia social. I. Título. CDD 158.2 741.58 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM “SOUTH PARK” Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Data da aprovação: 16/06/2011 COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Presidente: PROF. DR. JOSÉ STERZA JUSTO – UNESP/Assis Membros: PROF. DR. RAFAEL SIQUEIRA DE GUIMARÃES – UNICENTRO/ Irati PROF. DR. NELSON PEDRO DA SILVA – UNESP/Assis GRUDA, M. P. P. O discurso do humor politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park. -

Armistead Maupin

Armistead Maupin [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. Library podcasts are brought to you by The Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts, visit our web site at w w w dot SPL dot org. To learn how you can help the library foundation support The Seattle Public Library go to foundation dot SPL dot org [00:00:44] Today's program with Armistead Maupin. My name is David. I'm a librarian here and I have just a few words before we get started. This program today is sponsored by the Seattle Public Library Foundation, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. The foundation is made up of thousands of people in our community who give gifts, large and small to support our libraries. To all of the foundation donors who are here with us today. Thank you so much for your support. I would also like to recognize and thank The Seattle Times for their continued support for programming at the Seattle Public Library. We are delighted to be partnering with Seattle Pride Fest on this program. Also, thanks, go to the Elliott Bay Book Company for coordinating the book sales here this afternoon. As I said earlier, if you don't have all of his books, they can fix that for you. And if you do have all of his books. Think what a joy it would be to give those books to somebody else. Maybe if a fresh new set. -

Title Author Publication Year Publisher Format ISBN

Audre Lorde Library Book List Publication Title Author Publisher Format ISBN Year '...And Then I Became Savin-Williams, Ritch Routledge Paperback 9780965699860 Details Gay': Young Men's Stories C ]The Big Gay Book Psy.D., ABPP, John D. 1991 Plume Paperback 0452266211 Details (Plume) Preston ¿Entiendes?: Queer Bergmann, Emilie L; Duke University Readings, Hispanic 1995 Paperback 9780822316152 Details Smith, Paul Julian Press Writings (Series Q) 1st Impressions: A Cassidy James Mystery (Cassidy Kate Calloway 1996 Naiad Pr Paperback 9781562801335 Details James Mysteries) 2nd Time Around (A B- James Earl Hardy 1996 Alyson Books Paperback 9781555833725 Details Boy Blues Novel #2) 35th Anniversary Edition Sarah Aldridge 2009 A&M Books Paperback 0930044002 Details of The Latecomer 1000 Homosexuals: Conspiracy of Silence, or Edmund Bergler 1959 Pagent Books, Inc. Hardcover B0010X4GLA Details Curing and Deglamorizing Homosexuals A Body to Dye For: A Mystery (Stan Kraychik Grant Michaels 1991 St. Martin's Griffin Paperback 9780312058258 Details Mysteries) A Boy I Once Knew: What a Teacher Learned from her Elizabeth Stone 2002 Algonquin Books Hardcover 9781565123151 Details Student A Boy Named Phyllis: A Frank DeCaro 1996 Viking Adult Hardcover 9780670867189 Details Suburban Memoir A Boy's Own Story Edmund White 2000 Vintage Paperback 9780375707407 Details A Captive in Time (Stoner New Victoria Sarah Dreher 1997 Paperback 9780934678223 Details Mctavish Mystery) Publishers Incidents Involving Anna Livia Details Warmth A Comfortable Corner Vincent