A Guide to Effective Statewide Laws/Policies: Preventing Discrimination Against LGBT Students in K-12 Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Program Book

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN GHALLL OHF FAFME 2009 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Dana V. Starks Mayor Chairman and Commissioner Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues William W. Greaves, Ph.D. Director/Community Liaison COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, Suite 300 Chicago, Illinois 60654-3478 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) © 2009 Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame In Memoriam Robert Maddox Tony Midnite 2 3 4 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (now the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, their organizations and their friends, as well as their contributions to the LGBT communities and to the city of Chicago. -

Getting Down to Basics: Tools to Support LGBTQ Youth in Care, Child Welfare League a Place of Respect: a Guide for Group Care of Am

Getting Down to Basics Tools to Support LGBTQ Youth in Care Overview of Tool Kit Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) young people are in America’s child welfare and juvenile justice systems in disproportionate numbers. Like all young people in care, they have the right to be safe and protected. All too often, however, they are misunderstood and mistreated, leading to an increased risk of negative outcomes. This tool kit offers practical tips and information to ensure that LGBTQ young people in care receive the support and services they deserve. Developed in partnership by the Child Welfare League of America (CWLA) and Lambda Legal, the tool kit gives guidance on an array of issues affecting LGBTQ youth and the adults and organizations who provide them with out-of-home care. TOPICS INCLUDED IN THIS TOOL KIT 3 Basic Facts About Being LGBTQ 5 Information for LGBTQ Youth in Care 7 Families Supporting an LGBTQ Child FOSTERING TRANSITIONS 9 Caseworkers with LGBTQ Clients A CWLA/Lambda Legal 11 Foster Parents Caring for LGBTQ Youth Joint Initiative 13 Congregate Care Providers Working with LGBTQ Youth 15 Attorneys, Guardians ad Litem & Advocates Representing LGBTQ Youth 17 Working with Transgender Youth 21 Keeping LGBTQ Youth Safe in Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Placements 23 Working with Homeless LGBTQ Youth 25 Faith-Based Providers Working with LGBTQ Youth 27 Basic LGBTQ Policies, Training & Services for Child Welfare Agencies 29 Recommendations for Training & Education on LGBTQ Issues 31 What the Experts Say: Position & Policy Statements on LGBTQ Issues from Leading Professional Associations 35 LGBTQ Youth Resources 39 Teaching LGBTQ Competence in Schools of Social Work 41 Combating Misguided Efforts to Ban Lesbian & Gay Adults as Foster & Adoptive Parents 45 LGBTQ Youth Risk Data 47 Selected Bibliography CHILD WELFARE LEAGUE OF AMERICA CWLA is the nation’s oldest and largest nonprofit advocate for children and youth and has a membership of nearly 1000 public and private agencies, including nearly every state child welfare system. -

2016 Program Book

2016 INDUCTION CEREMONY Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame Gary G. Chichester Mary F. Morten Co-Chairperson Co-Chairperson Israel Wright Executive Director In Partnership with the CITY OF CHICAGO • COMMISSION ON HUMAN RELATIONS Rahm Emanuel Mona Noriega Mayor Chairman and Commissioner COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST Published by Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame 3712 North Broadway, #637 Chicago, Illinois 60613-4235 773-281-5095 [email protected] ©2016 Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame In Memoriam The Reverend Gregory R. Dell Katherine “Kit” Duffy Adrienne J. Goodman Marie J. Kuda Mary D. Powers 2 3 4 CHICAGO LGBT HALL OF FAME The Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame (formerly the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame) is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, its Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (later the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame (changed to the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 2015) in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. Today, after the advisory council’s abolition and in partnership with the City, the Hall of Fame is in the custody of Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame, an Illinois not- for-profit corporation with a recognized charitable tax-deductible status under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3). -

Basic Reforms to Address the Unmet Needs of Lgbt Foster Youth

II. BASIC REFORMS TO ADDRESS THE UNMET NEEDS OF LGBT FOSTER YOUTH What emerges from our state-by-state survey is a picture of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth under-served by foster care systems. These youth remain in the margins, their best interests ignored and their safety in jeopardy. To remedy LGBT invisibility, prevent abuse, and improve care for these adolescents, we propose the following crucial, basic reforms in the areas of non-discrimination policies, training for foster parents and foster care staff,48 and LGBT youth services and programs. A. Non-discrimination policies States should adopt and enforce explicit, systemwide policies prohibiting discrimina- tion. Specifically, these should include prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of: the sexual orientation of foster care youth, the sexual orientation of foster parents and other foster household members, the sexual orientation of foster care staff, the HIV/AIDS status of foster care youth, the HIV/AIDS status of foster parents and other foster household members, and the HIV/AIDS status of foster care staff. These policies should encompass actual or perceived sexual orientation or HIV/ AIDS status. Discrimination prohibitions should also forbid discrimination on the basis of gender identity. Sex discrimination provisions should be interpreted to bar such discrimi- nation, and that scope can be made explicit by enumerating sex, including gender identity, among forbidden bases of discrimination in agency policies. Adopting LGBT non-discrimination policies is an important acknowledgment that LGBT youth are present in the foster care system in significant numbers and that they 22 Youth in the Margins often face prejudice, neglect, and abuse. -

Download the Free QR Code Reader App

SUMMER 2018 Trans Victories in the Trump Era Protecting everyone against discrimination at work Religious Freedom ORWELLIAN LANGUAGE IS BACK IT’S A lifesaving victory: Life After PRIDE Prison Barbershop sued after turning down SEASON client with HIV SHOP OUR BRAND-NEW MERCHANDISE SHOP.LAMBDALEGAL.ORG equality for all: priceless® Mastercard is a proud sponsor of Lambda Legal and applauds their commitment to safeguard and advance the civil rights of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender people and those with HIV. Mastercard and Priceless are registered trademarks, and the circles design is a trademark of Mastercard International Incorporated. LAMBDA LEGAL IMPACT | Summer 2018 ©20128 Mastercard. All rights reserved. MCIH-17078_NYC_Pride_March_AdV1.indd 1 4/4/17 11:35 AM OVERPOWER THE BULLIES, WITH YOUR HELP generation from now, people look for opportunities to try our cases in front of juries and will ask why we didn’t do we will work with state attorneys general to protect LGBT more to fight back against people and everyone living with HIV. Trump and Pence. They are Of course, the irony is that right now we are winning Apacking the courts with judges who more cases than ever. More and more courts are holding we are distinguished primarily by their are right when we say that LGBT discrimination is a kind homophobia, transphobia and racism. of sex discrimination, and that both federal law and the Their reward is a permanent job Constitution protect us. We are winning cases for some of judging our lives. Neil Gorsuch is the most prominent, but the most vulnerable LGBTQ people in America—transgen- there are so many more. -

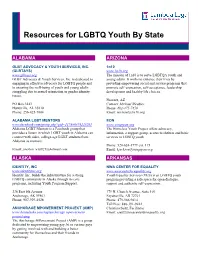

Resources for LGBTQ Youth by State

Resources for LGBTQ Youth By State ALABAMA ARIZONA GLBT ADVOCACY & YOUTH SERVICES, INC. 1n10 (GLBTAYS) www.1n10.org www.glbtays.org The mission of 1n10 is to serve LGBTQA youth and GLBT Advocacy & Youth Services, Inc. is dedicated to young adults. It works to enhance their lives by engaging in effective advocacy for LGBTQ people and providing empowering social and service programs that to ensuring the well-being of youth and young adults promote self‐expression, self‐acceptance, leadership struggling due to sexual orientation or gender identity development and healthy life choices. issues. Phoenix, AZ PO Box 3443 Contact: Michael Weakley Huntsville, AL 35810 Phone: 602-475-7456 Phone: 256-425-7804 Email: [email protected] ALABAMA LGBT MENTORS EON www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=117888378225291 www.wingspan.org Alabama LGBT Mentors is a Facebook group that The Homeless Youth Project offers advocacy, provides a forum in which LGBT youth in Alabama can information, a support group, access to shelters and basic connect with older, college-age LGBT students from services to LGBTQ youth. Alabama as mentors. Phone: 520-624-1779 ext. 115 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] ALASKA ARKANSAS IDENTITY, INC NWA CENTER FOR EQUALITY www.identityinc.org www.nwacenterforequality.org Identity, Inc. builds the infrastructure for a strong Youth Equality Services (YES) is an LGBTQ youth LGBTQ community in Alaska through its core program providing a safe space for open dialogue, programs, including Youth Program Support. support and -

Milestones in the United States'

MILESTONES IN THE UNITED STATES’ The landscape of LGBTQ+ rights has changed dramatically over the past 150+ years, most notably with legislation in 2015 supporting same-sex marriage. It is vital that our workplace recognize what it means to create a culture of inclusion and belonging and to understand what achieving LGBTQ+ equality truly requires. Below is a timeline that highlights the inception of LGBTQ+ organizations, important first fights against discrimination, and instrumental political and legal changes in the United States. 1867 Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs, “Father of the LGBT Movement,” becomes the first self-proclaimed homosexual to speak out publicly for gay rights at the Congress of German Jurists in Munich. 1903 The Ariston Bathhouse raid is the first anti-gay police raid on an establishment located in New York City. It results in 34 arrests, 16 charges of sodomy and 12 trials. 1924 The Society for Human Rights, the first gay rights organization in the United States, is founded by Henry Gerber in Chicago. It is shut down by police a few months later due to political pressure. 1952 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) lists homosexuality as a mental disorder in its first publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Immediately following the manual’s release, many medical, mental health and social science professionals criticize the categorization due to lack of empirical and scientific data. 1953 President Dwight Eisenhower signs Executive Order 10450, banning homosexuals from working for the federal government or any of its private contractors. The Order lists homosexuals as security risks, alcoholics and neurotics. -

Lambda Legal Annual Report 2009

MAKING THE CASE FOR EQUALITY LAMBDA LEGAL ANNUAL REPORT 2009 L ambda Legal is a national organization committed to achieving full recognition of the civil rights of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender people and those with HIV through impact litigation, education and public policy work. FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR The victory in Iowa illustrates how • An online adoption company learned Lambda Legal chooses its cases—for it couldn’t do business in New York if impact—and how freedom is won: by it barred gay couples from registering. digging in, doing the work and never • The rights of lesbian and gay parents giving up. in Ohio, Virginia, Florida and We depend on our members and Louisiana were protected. supporters to keep Lambda Legal • Providers of health care and other Persistence and impact—two strong. Here’s some of what we achieved services in Wisconsin and Arkansas words that describe the work we together in 2009: found out they can’t discriminate do at Lambda Legal. And two more • Georgia State Assembly officials against people with HIV without a words: victory and progress. learned they can’t fire an employee just fight. In 2009, we won incredible victories and for her gender transition or failure to As the pages that follow show, we made enormous progress. The victories conform to gender stereotypes—and if achieved all this and a great deal more in were the result of persistent, strategic they do, Lambda Legal will fight back. 2009. But many challenges lie ahead— work over many years. As we advanced • LGBT people now know that and persistence means that we won’t give equality, the impact was felt by LGBT California’s civil rights law prohibits up. -

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People and People Living with HIV Speak Out

When Health Care Isn’t Caring: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People and People Living with HIV Speak Out Since coming out, I have avoided seeing my primary physician because when she asked me my sexual history, I responded that I slept with women and that I was a lesbian. Her response was, “Do you know that’s against the Bible, against God?” –Kara, Philadelphia, PA As a gay male who has been HIV positive for 23 years, I have experienced so many biased and discriminatory actions from the first moment of receiving the news of my testing positive in a letter from a life insurance company to having doctors not wanting to even shake my hand. I had receptionists in doctors’ offices point out my status on my chart to other office and non-medical personnel and make disparaging remarks. A urologist refused treatment due to my HIV status, and in the past I have been refused health insurance simply because I have HIV. I now get my meds via mail order to avoid prejudice from pharmacy employees. My experiences have forced me back into the closet in many ways because I fear repercussions from anyone associated with medicine. – Robert, Location Withheld Many of us are vulnerable when we are ill or seeking attitudes and inflexible or prejudicial policies LGBT health care services. For lesbian, gay, bisexual and people and people living with HIV often encounter when transgender (LGBT) people and those living with HIV, they seek medical care. that vulnerability is often exacerbated by disrespectful attitudes, discriminatory treatment, inflexible or prejudicial policies and even refusals of essential care. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 12-144 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _______________________ DENNIS HOLLINGSWORTH, ET AL., Petitioners, v. KRISTIN M. PERRY, ET AL., Respondents. _____________________________ On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit _____________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. AND GAY & LESBIAN ADVOCATES & DEFENDERS IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS _____________________________ GARY D. BUSECK JON W. DAVIDSON MARY L. BONAUTO Counsel of Record Gay & Lesbian Advocates JENNIFER C. PIZER & Defenders Lambda Legal Defense and 30 Winter Street, Ste. 800 Education Fund, Inc. Boston, MA 02108 3325 Wilshire Blvd., # 1300 (617) 426-1350 Los Angeles, CA 90010 (213) 382-7600 [email protected] (Additional counsel on reverse page) Counsel for Amici Curiae (Additional Counsel for Amici Curiae) HAYLEY GORENBERG CAMILLA B. TAYLOR SUSAN L. SOMMER Lambda Legal Defense and Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. Education Fund, Inc. 105 West Adams, Ste. 2600 120 Wall Street, 19th Floor Chicago, IL 60604 New York, NY 10005 (312) 663-4413 (212) 809-8585 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................. i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iii INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE .............................. 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................ 2 ARGUMENT ................................................................ 5 I. PROPOSITION 8 IS UNIQUE ......................... 5 II. PROPOSITION 8 DENIES LESBIANS AND GAY MEN EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS IN THE MOST LITERAL SENSE............................................................... 9 III. PROPOSITION 8 ALSO FAILS RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW ......................... 11 A. Rational Basis Review is Attuned to Context ....................................................... 12 B. Proposition 8’s Termination of Same- Sex Couples’ Ability to Marry in California and Its Relegation of Those Couples Back to an Inferior Status Cannot Survive Rational Basis Review ... -

LGBTQ Resources: Websites and Publications

LGBTQ Resources: Websites and Publications Arizona Pima County Cenpatico Integrated Care - www.cenpaticointegratedcareaz.com LGBTQ Behavioral Health Coalition -www.facebook.com/LGBTQBHCoalition, www.lgbtqintegratedcoalition.wordpress.com/ SAGA - http://sagatucson.org/wp LGBTQI Living Out Loud Health and Wellness Center - www.livingoutloudaz.org Southern Arizona Aids Foundation - www.saaf.org (now home of Wingspan services) PFLAG - Tucson -http://www.pflagtucson.org Hope, Inc.- LGBTQ & Allies Group, www.hopetucson.org Cochise County Bisbee Pride – Annual Pride event site with resource links - www.bisbeepride.com Northern Arizona Northern AZ LGBT Community Resources- http://gayarizona.com/northern/resources/ Phoenix LGBTQ Consortium - http://www.lgbtconsortium.com Bridgeway Health Solutions- www.bridgewayhealthsolutions.com Health Net Access- www.healthnetaccess.com Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) - http://www.glsen.org/chapters/phoenix One Community - https://www.onecommunity.co/ Phoenix Pride Festival - http://phoenixpride.org/ Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS – AIDS services organization - http://swhiv.org/ Phoenix: Trans*Spectrum of Arizona - www.transspectrum.org One-N-Ten: Today’s Youth, Tomorrow’s Future - http://onenten.org/ Yavapai County Prescott Pride Center – serving the Prescott Community - https://www.facebook.com/pages/Prescott-Pride- Center/155272274512205 Greater Yavapai Community Coalition-Connecting the LGBTQ Community of Yavapai County – for more information Contact: [email protected] -

LGBT Rights Quiz How Well Do You Know Your History of LGBT and HIV Rights? the Legal Landscape Is Changing Every Day

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE LGBT Rights Quiz HOW WELL DO YOU KNOW YOUR HISTORY OF LGBT AND HIV RIGHTS? The legal landscape is changing every day. Are you up-to-date? Take this quiz highlighting Lambda Legal’s landmark litigation and find out. 1. JOHN LAWRENCE AND TYRON GARNER 2. IN 1993, 21-YEAR-OLD BRANDON TEENA 4. WHEN CIRQUE DU SOLEIL FIRED AERIAL were arrested in 1998 in Lawrence’s Houston was raped and later killed by two men who gymnast Matthew Cusick because of his HIV home after police who were responding to discovered he was transgender. Prior to the status, the Equal Employment Opportunity a false crime report found the men having killing, the sheriff not only notified the rapists Commission found (in Cusick v. Cirque du sex. The two men were convicted of violating that Teena had pressed charges against them Soleil, 2004): Texas’ “Homosexual Conduct” Law. When but also took no steps to protect Teena. a. That Cirque du Soleil’s concerns in this the Lambda Legal case, Lawrence v. Texas, (Teena’s life and death were the subject of the regard override the provisions of the Americans reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 2003, the Boys Don’t Cry 1999 film .) Teena’s mother, with Disabilities Act. justices struck down the law—and all similar JoAnn Brandon, sued. After a bad trial court state laws around the country, which had long ruling, Lambda Legal stepped in to help b. That Cirque du Soleil had likely engaged in been used to justify discrimination against with the appeal, and in 2001 the Nebraska illegal discrimination by violating the Americans LGBT people.