The Road to the Gettysburg Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burial Information for These Recipients Is Here

Civil War Name Connection Death Burial Allen, James Enlisted 31Aug1913 Oakland Cemetery Pottsdam, NY St Paul, MNH Anderson, Bruce Enlisted 22Aug1922 Green Hill Cemetery Albany, NY Amsterdam, NY Anderson, Charles W Served 25Feb1916 Thornrose Cemetery (Phorr, George) 1st NY Cav Staunton, VA Archer, Lester Born 27Oct1864 KIA - Fair Oaks, VA Fort Ann, NY IMO at Pineview Cemetery Queensbury, NY Arnold, Abraham Kerns Died 23Nov1901 St Philiips in the Highlands Church Cold Springs, NY Garrison, NY Avery, James Born 11Oct1898 US Naval Hospital New York City, NY Norfolk, VA Avery, William Bailey Served 29Jul1894 North Burial Grounds 1st NY Marine Arty Bayside, RI Baker, Henry Charles Enlisted 3Aug1891 Mount Moriah Cemetery New York City, NY Philadelphia, PA Barnum, Henry Alanson Born 29Jan1892 Oakwood Cemetery Jamesville, NY Syracuse, NY Barrell, Charles Luther Born 17Apr1913 Hooker Cemetery Conquest, NY Wayland, MI Barry, Augustus Enlisted 3Aug1871 Cold Harbor National Cemetery New York City, NY Mechanicsville, VA Barter, Gurdon H Born 22Apr1900 City Cemetery Williamsburg, NY Moscow or Viola, ID** Barton, Thomas C Enlisted Unknown - Lost to History New York City, NY Bass, David L Enlisted 15Oct1886 Wilcox Cemetery New York City, NY Little Falls, NY Bates, Delavan Born 19Dec1918 City Cemetery Seward, NY Aurora, NE Bazaar, Phillip Died 28Dec1923 Calvary Cemetery (Bazin, Felipe) New York City, NY Brooklyn, NY Beddows, Richard Enlisted 15Feb1922 Holy Sepulchre Cemetery Flushing, NY New Rochelle, NY Beebe, William Sully Born 12Oct1898 US Military -

Civil War Heritage

Civil War Heritage Day Albany Rural Cemetery, Menands, New York Saturday, September 13, 2008 Tours, Music, Events: 10 am - 5 pm Reception and Parade for President Lincoln! 3:00 pm On February 18, 1861 , Jefferson Davis was sworn in as President of the Confederacy and a celebration was held to mark the establishment of the Confederate States of America. On February 18, 1861 , Abraham Lincoln had been elected President of the United States but had not yet reached Washington. On February 18, 1861 , Abraham Lincoln was in Albany , New York. Albany’s Mayor George Thacher met Lincoln at the train station, and they rode in a carriage to the Capitol. As the carriage proceeded down Broadway and turned right to go up State Street, it passed Stanwix Hall, the current residence of John Wilkes Booth. Undoubtedly, Booth watched with almost all of Albany as the new President went by. Another spectator was Clara Harris, daughter of Senator Ira Harris. Clara and her fiancé Major Henry Rathbone would be reunited with President and Mrs. Lincoln at a later encounter with Booth. On June 7, 1862, in the midst of the war, the Trustees of Albany Rural donated a section named the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Plot. One hundred and forty-nine Civil War Veterans were buried in this plot and at least 600 more were buried in family plots throughout the cemetery. The Grand Army of the Republic Civil War Monument at Albany Rural contains the names of 648 Albany City residents who “ Died in Action.” The bronze plates on the monument were cast from a melted down Civil War cannon. -

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Daniel Webster Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1997 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78044925 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms000013 Prepared by Manuscript Division staff Expanded and revised by John McDonough and Nan Thompson Ernst Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2000 Revised 2010 April Collection Summary Title: Daniel Webster Papers Span Dates: 1800-1900 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1824-1852) ID No.: MSS44925 Creator: Webster, Daniel, 1782-1852 Extent: 2,500 items Extent: 16 containers Extent: 4 linear feet Extent: 8 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78044925 Summary: Lawyer, statesman, and diplomat; United States representative from New Hampshire and United States senator from Massachusetts. Correspondence, memoranda, notes and drafts for speeches, legal papers, invitations, printed matter, newspaper clippings, and other papers, chiefly dating from 1824 to 1852. Topics include Webster's law practices and cases heard before the United States Supreme Court, the Bank of the United States, diplomacy, national and state politics, slavery, and the Compromise of 1850. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Adams, John Quincy, 1767-1848. Archer, Charles--Correspondence. -

A Forgotten Confederate: John H. Ash's Story Rediscovered

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2017 A Forgotten Confederate: John H. Ash's Story Rediscovered Heidi Moye Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Moye, Heidi, "A Forgotten Confederate: John H. Ash's Story Rediscovered" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1565. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1565 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FORGOTTEN CONFEDERATE: JOHN H. ASH’S STORY REDISCOVERED by HEIDI MOYE (Under the Direction of Anastatia Sims) ABSTRACT A historical study of a southern family living in Savannah, GA from shortly before the election of 1860 through the Civil War years based on the journals of John Hergen Ash II (1843-1918). INDEX WORDS: John Hergen Ash, Savannah, GA, Antebellum South, Civil War, 5th Georgia Cavalry, Georgia Hussars, Estella Powers Ash, Laura Dasher Ash, Eutoil Tallulah Foy Ash A FORGOTTEN CONFEDERATE: JOHN H. ASH’S STORY REDISCOVERED by HEIDI MOYE B. A., Georgia Southern University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Georgia Southern University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS STATESBORO, GEORGIA © 2017 HEIDI MOYE All Rights Reserved 1 A FORGOTTEN CONFEDERATE: JOHN H. -

“John and Judith Sargent Murray” by Bonnie

John and Judith Sargent Murray By Bonnie Hurd Smith Author of From Gloucester to Philadelphia in 1790: Observations, anecdotes, and thoughts from the 18th-century letters of Judith Sargent Murray Introduction In Russell Miller’s opening paragraph in The Larger Hope about John Murray’s 1770 arrival in America he writes, “Little did he realize that he was to be the instrument by which a new and unique religious body was to be created, denominated Universalism, which was to challenge the grim Calvinism inherited from sixteenth-century Europe. Neither was he aware that the denomination which he would eventually help to found in America was to offer the hope of a spiritual democracy for a new nation.” And what of democracy for women – spiritual and political? The historian Susan Branson calls Judith Sargent Murray “the most important female essayist of the New Republic.” While John was preaching, traveling, organizing, and generally spreading the “good news” of Universalism, as taught to him by James Relly, Judith was publishing essays, plays, and a three-volume book (The Gleaner, 1798) to spread the “good news” of female equality, improving female education, and the “new era in female history” that young women were forging. These two extraordinary people first met in 1774, when Judith’s father, Winthrop Sargent, invited John to preach in Gloucester to a small group of “adherents” to Universalism. At the time, Judith was a 23-year-old married woman. John was 33, a widower, and an itinerant preacher from England who had been traveling throughout the colonies since 1770. After meeting the Gloucester Universalists, who were well organized and committed to Universalism, John decided to make the seaport town his home. -

UNIT HISTORIES Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of CIVIL WAR UNIT HISTORIES Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives Part 1. The Confederate States of America and Border States A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of CIVIL WAR UNIT HISTORIES Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives Part 1. Confederate States of America and Border States Editor: Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Civil War unit histories. The Confederate states of America and border states [microform]: regimental histories and personal narratives / project editors, Robert E. Lester, Gary Hoag. microfiches Accompanied by printed guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. ISBN 1-55655-216-5 (microfiche) ISBN 1-55655-257-2 (guide) 1. United States--History~Civil War, 1861-1865--Regimental histories. 2. United States-History-Civil War, 1861-1865-- Personal narratives. I. Lester, Robert. II. Hoag, Gary. III. Hydrick, Blair. [E492] 973.7'42-dc20 92-17394 CIP Copyright© 1992 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-257-2. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction v Scope and Content Note xiii Arrangement of Material xvii List of Contributing Institutions xix Source Note xxi Editorial Note xxi Fiche Index Confederate States of America Army CSA-1 Navy CSA-9 Alabama AL-15 Arkansas AR-21 Florida FL-23 Georgia GA-25 Kentucky KY-33 Louisiana LA-39 Maryland MD-43 Mississippi MS-49 Missouri MO-55 North Carolina NC-61 South Carolina SC-67 Tennessee TN-75 Texas TX-81 Virginia VA-87 Author Index AI-107 Major Engagements Index ME-113 INTRODUCTION Nothing in the annals of America remotely compares with the Civil War. -

Loudon Park National Cemetery Lodge

HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY LOUDON PARK NATIONAL CEMETERY, LODGE HALS No. MD-5-A Location: 3445 Frederick Avenue, Baltimore, (Independent City), Maryland. The coordinates for the Loudon Park National Cemetery, Lodge are 76.683404 W and 39.2722228 N, and they were obtained in August 2012 with, it is assumed, NAD 1983. There is no restriction on the release of the locational data to the public. Present Owner: National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Prior to 1988, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs was known as the Veterans Administration. The Veterans Administration took over management of Loudon Park National Cemetery from the U.S. Army in 1973 (Public Law 93-43). Date: 1885-86. Builder/Contractor: William Roussey. Description: The lodge for Loudon Park retained the three-room, L-shaped plan developed for the Second Empire style lodges, however, it assumed a Victorian-era cottage aesthetic with cross gable roofs, overhanging eaves, decorative bargeboards and brackets, paired double-hung sash glazed with two-over-two lights and operable shutters on the exterior. The millwork inside plus the built-in cabinet and corner stair contributed to the overall cottage-like characteristics of the building. The principal elevation faces west toward the entrance drive. The building is two stories in height and was constructed of brick, complete with a water table. The chimneys were built of brick as well. Granite was used for the sills. Inside, the floors are wood, and the wood doors are paneled. In the mid-1920s electricity came to the lodge, and by the decade’s end, its heating system had been modernized as well. -

Return to Sender: Responses to Professor Carrington Et Al

FEATURE RETURN TO SENDER: RESPONSES TO PROFESSOR CARRINGTON ET AL. REGARDING FOUR PROPOSALS FOR A JUDICIARY ACT OF 2009 * David C. Dziengowski INTRODUCTION “Periodical appointments, however regulated, or by whomsoever made, would, in some way or other, be fatal to their necessary independence.”1 At the conclusion of the American Revolution in 1783, the average human lifespan was about thirty-five years.2 The Framers, dissatisfied with the Articles of Confederation, convened the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 25, 1787. Article III of the resulting U.S. Constitution provided judges of the “supreme and inferior Courts” with presumptive life tenure.3 Fast-forward more than two centuries. The average human lifespan in the United States is now over seventy-seven years.4 Due in part to the increase in longevity, the average term of years a Supreme Court Justice serves is * Lieutenant Junior Grade, United States Navy JAG Corps; J.D., Rutgers School of Law–Camden, 2008; B.A. History, The College of New Jersey, 2005. I wish to thank the Honorable Joseph H. Rodriguez, Senior U.S.D.J., for reviewing an earlier draft of this Article and providing helpful thoughts and suggestions. The opinions expressed herein are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Navy or the Department of Defense. Any errors or omissions are similarly my own. 1. THE FEDERALIST NO. 78, at 471 (Alexander Hamilton) (Clinton Rossiter ed., 1961). 2. CHRISTOPHER WANJEK, BAD MEDICINE: MISCONCEPTIONS AND MISUSES REVEALED, FROM DISTANCE HEALING TO VITAMIN O 70 (2003). 3. -

Judith Sargent Murray: the "So-Called" Feminist

Constructing the Past Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 4 2000 Judith Sargent Murray: The "So-Called" Feminist Sara Scobell Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Scobell, Sara (2000) "Judith Sargent Murray: The "So-Called" Feminist," Constructing the Past: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Judith Sargent Murray: The "So-Called" Feminist Abstract This article discusses the writings of Judith Murray, and critiques the notion that she was an early feminist and supporter of women's right to move outside of the domestic sphere. This article is available in Constructing the Past: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol1/iss1/4 Sara Scobell 4 Constructing The Past 5 Judith Sargent Murray: The''So-Ca1led'' Femlntit extensively upon Judith Sargent Murray's published essays, short stories, and plays. -

Genealogical Sketch Of

Genealogy and Historical Notes of Spamer and Smith Families of Maryland Appendix 2. SSeelleecctteedd CCoollllaatteerraall GGeenneeaallooggiieess ffoorr SSttrroonnggllyy CCrroossss--ccoonnnneecctteedd aanndd HHiissttoorriiccaall FFaammiillyy GGrroouuppss WWiitthhiinn tthhee EExxtteennddeedd SSmmiitthh FFaammiillyy Bayard Bache Cadwalader Carroll Chew Coursey Dallas Darnall Emory Foulke Franklin Hodge Hollyday Lloyd McCall Patrick Powel Tilghman Wright NEW EDITION Containing Additions & Corrections to June 2011 and with Illustrations Earle E. Spamer 2008 / 2011 Selected Strongly Cross-connected Collateral Genealogies of the Smith Family Note The “New Edition” includes hyperlinks embedded in boxes throughout the main genealogy. They will, when clicked in the computer’s web-browser environment, automatically redirect the user to the pertinent additions, emendations and corrections that are compiled in the separate “Additions and Corrections” section. Boxed alerts look like this: Also see Additions & Corrections [In the event that the PDF hyperlink has become inoperative or misdirects, refer to the appropriate page number as listed in the Additions and Corrections section.] The “Additions and Corrections” document is appended to the end of the main text herein and is separately paginated using Roman numerals. With a web browser on the user’s computer the hyperlinks are “live”; the user may switch back and forth between the main text and pertinent additions, corrections, or emendations. Each part of the genealogy (Parts I and II, and Appendices 1 and 2) has its own “Additions and Corrections” section. The main text of the New Edition is exactly identical to the original edition of 2008; content and pagination are not changed. The difference is the presence of the boxed “Additions and Corrections” alerts, which are superimposed on the page and do not affect text layout or pagination. -

Supreme Court Justices

The Supreme Court Justices Supreme Court Justices *asterick denotes chief justice John Jay* (1789-95) Robert C. Grier (1846-70) John Rutledge* (1790-91; 1795) Benjamin R. Curtis (1851-57) William Cushing (1790-1810) John A. Campbell (1853-61) James Wilson (1789-98) Nathan Clifford (1858-81) John Blair, Jr. (1790-96) Noah Haynes Swayne (1862-81) James Iredell (1790-99) Samuel F. Miller (1862-90) Thomas Johnson (1792-93) David Davis (1862-77) William Paterson (1793-1806) Stephen J. Field (1863-97) Samuel Chase (1796-1811) Salmon P. Chase* (1864-73) Olliver Ellsworth* (1796-1800) William Strong (1870-80) ___________________ ___________________ Bushrod Washington (1799-1829) Joseph P. Bradley (1870-92) Alfred Moore (1800-1804) Ward Hunt (1873-82) John Marshall* (1801-35) Morrison R. Waite* (1874-88) William Johnson (1804-34) John M. Harlan (1877-1911) Henry B. Livingston (1807-23) William B. Woods (1881-87) Thomas Todd (1807-26) Stanley Matthews (1881-89) Gabriel Duvall (1811-35) Horace Gray (1882-1902) Joseph Story (1812-45) Samuel Blatchford (1882-93) Smith Thompson (1823-43) Lucius Q.C. Lamar (1883-93) Robert Trimble (1826-28) Melville W. Fuller* (1888-1910) ___________________ ___________________ John McLean (1830-61) David J. Brewer (1890-1910) Henry Baldwin (1830-44) Henry B. Brown (1891-1906) James Moore Wayne (1835-67) George Shiras, Jr. (1892-1903) Roger B. Taney* (1836-64) Howell E. Jackson (1893-95) Philip P. Barbour (1836-41) Edward D. White* (1894-1921) John Catron (1837-65) Rufus W. Peckham (1896-1909) John McKinley (1838-52) Joseph McKenna (1898-1925) Peter Vivian Daniel (1842-60) Oliver W. -

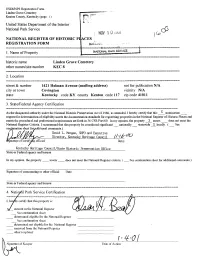

Nov 3 0 ^ National Register of Historic Pi Aces Registration Form

USDI/NPS Registration Form Linden Grove Cemetery Keuton County, Kentucky (page 1) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 3 0 ^ NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PI ACES REGISTRATION FORM ______,_____________________________________________n -r.. , , ,,.._________________________________________„,.__________________1 __________._______________.____M___.__"-JM—i—— f I I J j J.J. j j'll} iM.________________^^ -__,- ____ __|,___-^-___ ___._.-^——,^IL ,^—— ^ —— ___,—————————~——————..____ - ———— 1. Name of Property NAflGNAL PAHK SERVICE historic name Linden Grove Cemetery other names/site number KEC8 2. Location street & number 1421 Holman Avenue (mailing address) not for publication N/A city or town Covington vicinity N/A state Kentucky code KY county Kenton code 117 zip code 41011 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended. I hereby certify that this ^ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __ nationally __ statewide X locally. ( __ See continuation sheet foryadditional comments.) David L. Msrgan, SHPO and Executive Director, Kentucky Heritage Council (> fgnature of certifying official Date Kentucky Heritage Council/State Historic Preservation Office______ State or Federal agency and bureau hi my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. ( __ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4.