The Dramaturgy of SWEENEY TODD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Littlewood Education Pack in Association with Essentialdrama.Com Joan Littlewood Education Pack

in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan LittlEWOOD Education pack in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan Littlewood Education PAck Biography 2 Artistic INtentions 5 Key Collaborators 7 Influences 9 Context 11 Productions 14 Working Method 26 Text Phil Cleaves Nadine Holdsworth Theatre Recipe 29 Design Phil Cleaves Further Reading 30 Cover Image Credit PA Image Joan LIttlewood: Education pack 1 Biography Early Life of her life. Whilst at RADA she also had Joan Littlewood was born on 6th October continued success performing 1914 in South-West London. She was part Shakespeare. She won a prize for her of a working class family that were good at verse speaking and the judge of that school but they left at the age of twelve to competition, Archie Harding, cast her as get work. Joan was different, at twelve she Cleopatra in Scenes from Shakespeare received a scholarship to a local Catholic for BBC a overseas radio broadcast. That convent school. Her place at school meant proved to be one of the few successes that she didn't ft in with the rest of her during her time at RADA and after a term family, whilst her background left her as an she dropped out early in 1933. But the outsider at school. Despite being a misft, connection she made with Harding would Littlewood found her feet and discovered prove particularly infuential and life- her passion. She fell in love with the changing. theatre after a trip to see John Gielgud playing Hamlet at the Old Vic. Walking to Find Work Littlewood had enjoyed a summer in Paris It had me on the edge of my when she was sixteen and decided to seat all afternoon. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street May 10 – June 7, 2020 Edu TABLE of CONTENTS

A NOISE WITHIN’S 2019-2020 REPERTORY THEATRE SEASON AUDIENCE GUIDE Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd The Demon Barber Of Fleet Street May 10 – June 7, 2020 Edu TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Map . 3 Synopsis . 4 About the Author: George Dibdin Pitt . 5 About the Adaptors: Christopher Bond, Hugh Wheeler, and Stephen Sondheim . 7 History of Sweeney Todd: A Timeline . 9 Change in the Air: The Transition from the Industrial Revolution to the Victorian Era . 10 Pretty Women: The Role of Women in 19th Century England . 11 The Great Divide: Social Inequality in Industrial and Victorian England . 14 Melodrama and Musicals . 15 The Evolution of the Sweeney Todd Story from Melodrama to Musical . 17 Themes . 18 Revenge . 18 Love and Desire . 18 Freedom and Captivity . 19 Madness . 19 Ken Booth Lighting Designer . 20 Additional Resources . 21 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: Ann Peppers Foundation The Green Foundation Capital Group Companies Kenneth T . and Michael J . Connell Foundation Eileen L . Norris Foundation The Dick and Sally Roberts Ralph M . Parsons Foundation Coyote Foundation Steinmetz Foundation The Jewish Community Dwight Stuart Youth Fund Foundation 3 A NOISE WITHIN 2019/20 REPERTORY SEASON | Spring 2020 Study Guide Sweeney Todd CHARACTER MAP Mrs. Lovett The owner of a struggling meat pie shop . She knew Sweeney Todd before he was sent to Australia, and she helps him set up a barbershop when he returns to London . Sweeney Todd/Benjamin Barker An English barber formerly known Beggar Woman/Lucy Barker as Benjamin Barker . After spending A woman who has gone mad over 15 years wrongfully incarcerated in time . -

The Premiere Fund Slate for MIFF 2021 Comprises the Following

The MIFF Premiere Fund provides minority co-financing to new Australian quality narrative-drama and documentary feature films that then premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). Seeking out Stories That Need Telling, the the Premiere Fund deepens MIFF’s relationship with filmmaking talent and builds a pipeline of quality Australian content for MIFF. Launched at MIFF 2007, the Premiere Fund has committed to more than 70 projects. Under the charge of MIFF Chair Claire Dobbin, the Premiere Fund Executive Producer is Mark Woods, former CEO of Screen Ireland and Ausfilm and Showtime Australia Head of Content Investment & International Acquisitions. Woods has co-invested in and Executive Produced many quality films, including Rabbit Proof Fence, Japanese Story, Somersault, Breakfast on Pluto, Cannes Palme d’Or winner Wind that Shakes the Barley, and Oscar-winning Six Shooter. ➢ The Premiere Fund slate for MIFF 2021 comprises the following: • ABLAZE: A meditation on family, culture and memory, indigenous Melbourne opera singer Tiriki Onus investigates whether a 70- year old silent film was in fact made by his grandfather – civil rights leader Bill Onus. From director Alex Morgan (Hunt Angels) and producer Tom Zubrycki (Exile in Sarajevo). (Distributor: Umbrella) • ANONYMOUS CLUB: An intimate – often first-person – exploration of the successful, yet shy and introverted, 33-year-old queer Australian musician Courtney Barnett. From producers Pip Campey (Bastardy), Samantha Dinning (No Time For Quiet) & director Danny Cohen. (Dist: Film Art Media) • CHEF ANTONIO’S RECIPES FOR REVOLUTION: Continuing their series of food-related social-issue feature documentaries, director Trevor Graham (Make Hummus Not War) and producer Lisa Wang (Monsieur Mayonnaise) find a very inclusive Italian restaurant/hotel run predominately by young disabled people. -

CH Sweeney SSC Breakdown.Pdf

Sweeney Todd / Cambria Heights High School Scene / Song Character Breakdown Song Name/Scene Real Name Character Name Music Notes Act 1 - Prologue #1 - Prologue Script Pg. 1 Vocal Score Pg. -- Entire Prologue (none) (none) (none) #2 The Ballad of Sweeney Todd Script Pg. 1-3 Vocal Score Pg. 141-151 m. 59-74 & m. 114-136 m. 139-end Timm Link 1st Man, m. 4 S - Sarah, Lydia, Ashley, Noelle Morrone 2nd Man, m. 31 Lauren, Noelle P. (See Music Columns) Company, Chorus A - Courtney, Emily, Sheldon Mayo Tobias, m. 78 Shaina, Alli, Andrea, Shaina Sclesky 3rd Man, m. 83 Hannah Kyle Huber 4th Man, m. 86 T - Noelle M, Michaela, In octaves. Sing the octave that is most Emmy Fisher 1 of 2 Women, m. 91 Georgie, Emmy comfortable. Hannah Bearer 2 of 2 Women, m. 91 Bari - Evan J, Brad, Zachary Smego Add Tenor, m. 88 Sheldon, Calem All Women in Cast Women, m. 102 Bass - Timm, Kyle, Evan K, Zack, Michael John Morrone Todd, m. 137 do not sing Act 1 - Scene 1 #3 - No Place Like London Script Pg. 3-8 Vocal Score Pg. 152-160 Entire Song Zachary Smego Anthony John Morrone Todd Solo Lines, No Harmony Emmy Fisher Beggar Woman #4 - Transition Music Script Pg. 8-9 Vocal Score Pg. -- Entire Transition Hannah Bearer Mrs. Lovett Spoken Line Act 1 - Scene 2 #5 - Worst Pies In London Script Pg. 9-11 Vocal Score Pg. 161-166 Entire Song John Morrone Todd Just Present During Song Hannah Bearer Mrs. Lovett Solo Lines Scene Script Pg. -

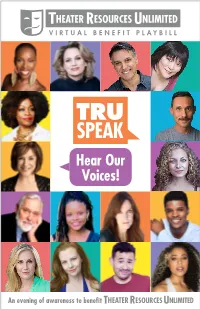

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

Little Shop of Horrors

PRESENTS LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS Book and Lyrics by Music by HOWARD ASHMAN ALAN MENKEN Based on the film by Roger Corman Screenplay by Charles Griffith Directed by Bill Fennelly September 10 – October 16, 2016 Artistic Director | Chris Coleman LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS Music by Book and Lyrics by ALAN MENKEN HOWARD ASHMAN Based on the film by Roger Corman Screenplay by Charles Griffith Directed by Bill Fennelly Music Supervisor Choreographer Scenic Designer Rick Lewis Kent Zimmerman Michael Schweikardt Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Kathleen Geldard William C. Kirkham Casi Pacilio Original Vocal Original Orchestrations Fight Director Arrangements Robert Merkin John Armour Robert Billig Stage Manager Dance Captain Assistant Stage Manager Mark Tynan* Johari Nandi Mackey* JanineVanderhoff* Production Assistants New York Casting Local Casting Bailey Anne Maxwell Harriet Bass Brandon Woolley Stephen Kriz Gardner *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. CAST LIST Chiffon Johari Nandi Mackey* Crystal Alexis Tidwell* Ronnette Ebony Blake* Mushnik David Meyers* Audrey Gina Milo* Seymour Nick Cearley* Orin Jamison Stern* The Voice of Audrey II/Wino 1 Chaz Rose* Audrey II Manipulation Stephen Kriz Gardner *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Co-produced with Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, Blake Robison, Artistic Director, and Buzz Ward, Managing Director. Originally produced by the WPA Theatre (Kyle Renick, Producing Director). Originally produced at the Orpheum Theatre, New York City, by the WPA Theatre, David Geffen, Cameron Mackintosh and the Shubert Organization. Little Shop of Horrors was originally directed by Howard Ashman with musical staging by Edie Cowan. -

AUGUSTANA COLLEGE THEATRE 2015-2016 Season Crime and Justice

AUGUSTANA COLLEGE THEATRE 2015-2016 Season Crime and Justice WVIK WVIKWVIK WVIis a proud WVIK partner in theWV Quad Cities’ WVIKarts and cultureWV WVIKcommunity WVIKWVIK WVIKWVIKWVIKwvik.org Augustana College Department of Theatre Arts, in conjunction with Opera@Augustana, proudly presents SWEENEY TODD The Demon Barber of Fleet Street A Musical Thriller Music and lyrics by Book by STEPHEN SONDHEIM HUGH WHEELER From an adaptation by CHRISTOPHER BOND Originally directed on Broadway by HAROLD PRINCE Orchestrations by JONATHAN TUNICK Originally produced on Broadway by RICHARD BARR, CHARLES WOODWARD, ROBERT FRYER, MARY LEA JOHNSON, MARTIN RICHARDS in association with DEAN and JUDY MANOS Directed by Music direction by JAY CRANFORD MICHELLE CROUCH SWEENEY TODD is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials also are supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR What a large undertaking in a short amount of time with Sondheim’s most difficult score! Kudos to the cast, crew, musical, technical and design team. Sondheim’s masterpiece about a wronged barber seeking revenge has long been a favorite of mine. Having seen the recent John Doyle Broadway revival on their final dress rehearsal, I caught Sondheim there looking perturbed. It had been deconstructed with the small cast playing their own instruments as they sang; clear storytelling had been lost. In our version, I wanted to focus completely on the relationships and reasons that drive Sweeney to action. A corrupt judge of powerful stature does the unimaginable, giving permission to a society in downward spiral to lose all sense of morality. -

Theatre Breaking Through Barriers

EQUITYACTORS’ EQUITY: STANDING UP FOR OURNEWS MEMBERS JUNE 2015 / Volume 100 / Number 5 www.actorsequity.org 2015 Equity Theater BreakingThrough Barriers Election Results Continues to Provide Work for Kate Shindle elected President of the union; all other officers reelected and 16 elected to Council Performers With Disabilities Kate Shindle led 1st Vice President Not elected: Dan NicholasViselli is the new Artistic Director the slate of officers Paige Price Zittel, Eric H. Mayer Photo by Carol Rosegg elected to three-year 2nd Vice President By Helaine Feldman terms in Equity’s 2015 The following candi- Rebecca Kim Jordan he stage is the way national election. In date was nominated 3rd Vice President to change the addition, 16 members with no opposition “ Ira Mont world,” said Ike — 11 from the East- and, pursuant to Rule T Schambelan, founder and ern Region, 2 from the Secretary/Treasurer VI(E)6 of the Nomina- artistic director of Theater Central Region and 3 Sandra Karas tions and Election Breaking Through Barriers from the Western Re- Eastern Regional Policy, has been (formerly Theater By the gion — have been Vice President deemed elected. Blind) until his death on elected to Council. Melissa Robinette Chorus February 3, 2015. Nicholas Ballots were tabu- Central Regional Bill Bateman Viselli, who joined the lated on May 21, Vice President company in 1997 and has 2015. There were Dev Kennedy CENTRAL been named to continue 6,182 total valid bal- REGION Schambelan’s work, agrees The cast of Agatha Christie’s The Unexpected Guest, including lots cast, of which EASTERN The following candi- with the late artistic director’s (L to R) Pamela Sabaugh, Scott Barton, Melanie Boland, Ann 3,397 were cast elec- REGION Marie Morelli, Lawrence Merritt and David Rosar Stearns. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

2 November 2012 Page 1 of 7 SATURDAY 27 OCTOBER 2012 Benedict

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 27 October – 2 November 2012 Page 1 of 7 SATURDAY 27 OCTOBER 2012 Benedict. Richard Mills - a vulnerable old man - is attacked and burgled. SAT 05:00 Old Dog and Partridge (b007w3j9) He seems lonely so Detective Inspector Gwen Danbury decides SAT 00:00 Philip K Dick - Of Withered Apples (b007jplz) Episode 4 to introduce him to her mother, Joan... As a beautiful woman picks its last withered apple, a dying A ladykiller woos Mrs Drummond and Nicola is determined to Sue Rodwell's three-part detective mystery stars Annette ancient tree is determined to survive. Read by William find the right present for her dad Jack's birthday. Badland as DI Gwen Danbury, Stephanie Cole as Joan Danbury, Hootkins. Joe Turner’s six-part sitcom stars Michael Williams as Jack, Ian Hogg as Richard Mills, Richard Frame as Darren Peters and SAT 00:30 Ben Moor - Undone (b00pkvk9) Lisa Coleman as Nicola, Cherry Morris as Mrs Drummond, John Duttine as Detective Sergeant Henry Jacobs Series 3 Simon Greenall as Andy and Finetime Fontayne as Arthur. Director: Rosemary Watts Unending Producer: Liz Anstee First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2002. The Notting Hill Carnival sees the potential end of the worlds First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in January 1999. SAT 14:00 Listen to Les (b01nh8zx) and new weirdness. Ben Moor's comic sci-fi saga with Alex SAT 05:30 Up the Garden Path (b00803k9) From 10/03/1985 Tregear. Series 2 Les Dawson with tales of Britain's first space hero, and the SAT 01:00 Sherlock Holmes (b00kkdkp) Arrivals and Departures Cosmo show discusses birds. -

1-24-17 Opera Workshop

Williams Opera Workshop SWEENEY TODD The Demon Barber of Fleet Street A Musical Thriller Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN SONDHEIM ’50 HUGH WHEELER From an Adaptation by CHRISTOPHER BOND Originally Directed On Broadway by HAROLD PRINCE Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Originally Produced on Broadway by Richard Barr, Charles Woodward, Robert Fryer, Mary Lea Johnson, Martin Richards in Association with Dean and Judy Manos Prelude Prologue: The Ballad of Sweeney Todd . Todd, Company Act I Scenes: 1. A street by the London docks: No Place Like London . Anthony, Todd, Beggar Woman 2. Mrs. Lovett’s Pie Shop: Worst Pies in London . Mrs. Lovett My Friends . Todd, Mrs. Lovett Ballad of Sweeney Todd, Reprise . Company 3. Judge Turpin’s House: Green Finch and Linnet Bird . Johanna Johanna (Part 1 & 2) . Anthony 4. St. Dunstan’s marketplace: Pirelli’s Entrance . Pirelli The Contest (Part 1) . Pirelli 5. Sweeney Todd’s Tonsorial Parlor: Pirelli’s Death . Pirelli 6. Outside Judge Turpin’s house: Kiss Me (Part 1) . Johanna, Anthony Ladies in their Sensitivities . Beadle 7. Sweeney Todd’s Tonsorial Parlor: Pretty Women (Part 1) . Judge, Todd Pretty Women (Part 2) . Todd, Judge, Anthony Epiphany . Todd, Mrs. Lovett 8. Mrs. Lovett’s Pie Shop: A Little Priest . Mrs. Lovett, Todd Continued on reverse side Tuesday, January 24, 2017 7:00 p.m. Chapin Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. Act 2 9. The streets of London: Johanna—Act 2 Sequence . Anthony, Todd, Johanna, Beggar Woman 10. Mrs. Lovett’s Pie Shop: Not While I’m Around .