Lecture 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English, French, Hindi, Japanese, Europe and Central Asia 42 Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish

THE WORLD BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2008 THE WORLD 46256 THE WORLD BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2008 YEAR IN REVIEW YEAR IN REVIEW Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1818 H St NW ISBN 978-0-8213-7675-1 Washington DC 20433 USA THE WORLD BANK Telephone: 202-473-1000 Facsimile: 202-477-6391 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] SKU 17675 THE WORLD BANK OPERATIONAL SUMMARY | FISCAL 2008 ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Offi ce of the Publisher, External Affairs IBRD MILLIONS OF DOLLARS 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 Team Leader Commitments 13,468 12,829 14,135 13,611 11,045 Richard A. B. Crabbe Of which development policy lending 3,967 3,635 4,906 4,264 4,453 Editor Number of projects 99 112 113 118 87 Cathy Lips Of which development policy lending 16 22 21 23 18 Assistant Editor Gross disbursements 10,490 11,055 11,833 9,722 10,109 Belinda Yong Of which development policy lending 3,485 4,096 5,406 3,605 4,348 Editorial Production Principal repayments (including prepayments) 12,610 17,231 13,600 14,809 18,479 Cindy A. Fisher Aziz Gökdemir Net disbursements (2,120) (6,176) (1,767) (5,087) (8,370) Mary C. Fisk Loans outstanding 99,050 97,805 103,004 104,401 109,610 Dina Towbin Undisbursed loans 38,176 35,440 34,938 33,744 32,128 Print Production Randi Park Operating incomea 2,271 1,659 1,740 1,320 1,696 Denise Bergeron Usable capital and reserves 36,888 33,754 33,339 32,072 31,332 Project Assistant Attiya Zaidi Equity-to-loans ratio 38% 35% 33% 31% 29% The World Bank Annual a. -

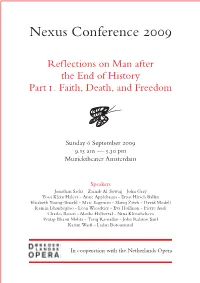

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Worldviews and the Transformation to Sustainable Societies Hedlund-de Witt, A. 2013 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Hedlund-de Witt, A. (2013). Worldviews and the Transformation to Sustainable Societies: An exploration of the cultural and psychological dimensions of our global environmental chanllenges. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 to sustainable societies sustainable to and the transformation Worldviews Worldviews and the transformation to sustainable societies Worldviews and the transformation Worldviews and the transformation to sustainable societies addresses one of the most challenging questions of our time. Its unique vantage point is based on the recognition of the to sustainable societies crucial importance of worldviews vis-à-vis the urgently needed transformation to sustainable An exploration of the cultural and psychological societies. -

Food (Safety) Policy in the Netherlands

210 CHAPTER SIX: From ‘politics in the stable’ to stable politics: Food (safety) policy in the Netherlands 6.1 Introduction In his 1999 book De Virtuele Boer (‘The virtual farmer’), Jan Douwe van der Ploeg critically addressed the evolution of the Dutch ‘expertise-based’ intensive agriculture, which, according the author, had constructed an image of the farmer as focused on profit-maximizing and as virtually indifferent to the societal and environmental impact of intensive agriculture. Upon its publication, commentators referred to it as ‘not discussable’ (onbespreekbaar) at Wageningen University (Strijker 2000: 8), the long-standing agricultural university and breeding ground for the exceptional rate of success of Dutch agriculture - one of the largest exporters of agricultural products. What makes such criticism ‘not discussable’, and how does it compare to the desire to ‘remove the smell of stables’ from food (safety) policy in England and Germany, following the series of food scares during the 1990s? The present chapter explores the ways in which food (safety) has been taken up as a policy issue in the Netherlands and addresses the underlying contextual specificities in the following ways: Following this introduction, section 2 provides an account of the developments in the area of food (safety) policy in the Netherlands roughly over the past century in order to trace out some of the discursive-institutional foundations that still carry weight in today’s policy discourse. As in the previous two country-based chapters, section 3 recounts the range of food scares that occurred in the Netherlands over the past decade and highlights the key moments in which particular interpretations of ‘what food safety means’, and what the food scares stood for, were articulated. -

CV Tim Haarlemmer

Curriculum Vitae Tim Haarlemmer General Information Full name : Tim Haarlemmer Address : Vincentiuspad 4 5038SL Tilburg The Netherlands Phone number : +316-12960246 E-mail : [email protected] Date of birth : 15-02-1989 Place of birth : Tiel, The Netherlands Nationality : Dutch Gender : Male Education 2010-2011: MSc. Global Business and Stakeholder Management, Rotterdam School of Management (Erasmus University), cum laude (average grade: 8,7/10) Master Thesis: “ How Modern Corporate Ideology and Its Mechanisms Systematically Erode Ethical Behaviour ” (graded 8,5/10) 2008-2010: Honours Programme Tilburg University (average grade: 8,4/10) 2007-2010: Minor Philosophy (average grade: 8,1/10) 2007-2010: BSc. Bachelor International Business Administration, Tilburg University: cum laude. Bachelor Thesis: “ Dynamic Capabilities and the Bottom of the Pyramid: Exploring Firm Requirements ” (graded 8/10). Awarded with ‘Excellence Scholarship’ for top 3% tier of student population 2001-2007: VWO degree, E&M profile: RSG Lingecollege, Tiel Work experience 2011: Having my own little start-up in leading discussions, debates, guiding game sessions. Former clients: Tilburg University (interviewing CEO Grolsch), conglomerate of NGO’s (leading a political debate, Breda), HYPE (leading a negotiation game, Utrecht), and ROC Tilburg (debating) 2011 (summer): ‘Bedrijfshulpverlener’ (first aid) at Tilburg University 2009 (summer): Club Life in Rimini, Italy. Function in PR, attracting and maintaining customers 2008 (winter): Jos Hofkens HIG freelance consultant on a Business Plan, Oosterhout 2008 (autumn): D&F Consulting: project freelancer, Etten-Leur 2008 (summer): Club Life in Rimini, Italy. Function in PR, attracting and maintaining customers 2006 (April-August): Albert Heijn supermarket, Tiel. 2005 – 2007: Hospital Rivierenland: Parking lot manager, Tiel Project experience 2011: Ordina N.V., recommendations concerning strategic employee alignment in changing environment 2009: Business Plan Jos Hofkens HIG B.V., external analysis. -

Een Pdf-Bestand Van Het Boek Downloaden

Duurzaam Rutte III: de stille triomf van Diederik Samsom Vrij Nederland 2017 © 2017 Weekbladpersgroep BV, Amsterdam. Hoe het duurzame Rutte III een stille triomf is van Diederik Samsom Door Thijs Broer en Max van Weezel I 10 oktober 2017. In de Oude Zaal van de Tweede Kamer hebben zich tientallen cameraploegen, schrijvende journalisten en belangstellende Kamerleden verzameld. Via een zijdeur betreden premier Rutte en zijn drie nieuwe coalitiegenoten Sybrand Buma (CDA), Alexander Pechtold (D66) en Gert-Jan Segers (ChristenUnie) de voormalige balzaal van stadhouder Willem V. Glunderend van trots komen ze een voor een het regeerakkoord ‘Vertrouwen in de toekomst’ toelichten. Rutte, bekend van de uitspraak ‘Die gekke windmolens draaien niet op wind maar vooral op subsidie’, vestigt de aandacht op de ambitieuze klimaatagenda van het kabinet in wording: ‘We gaan hard werken aan een duurzame samenleving waarin ook onze kinderen en kleinkinderen gezond kunnen opgroeien.’ Hij is nog geen minuut aan het woord of de aanwezige journalisten zien op hun smartphone een twitterbericht van D66 verschijnen: ‘Wij zijn trots op het groenste regeerakkoord ooit!’ Even later verklaart Pechtold vanachter de katheder: ‘Dit kabinet haalt de klimaatdoelen van Parijs en verandert Nederland van een zorgelijke achterblijver in een Europese koploper.’ Tijdens de interviews na afloop telt Segers zijn zegeningen. Hij zegt het D66 na: ‘Dit is het meest groene kabinet dat er ooit is geweest.’ De verslaggevers leggen vooral Sybrand Buma het vuur na aan de schenen, want diens partijgenoot Herman Wijffels heeft hem tijdens de formatie vergeleken met klimaatontkenner Donald Trump (‘Die man heeft helemaal niets met het duurzaamheidsvraagstuk’). -

Women in Economics: a Lifelong Discouragement

ESB Solutions ESB Solutions EXPOSITION Women in economics: a lifelong discouragement The gender gap in economics science is worse than in other Although understandable as an initial hypothesis, this disciplines. Are women treated differently than men, in does not do justice to existing knowledge, also in eco- nomics, about the influence of environmental factors school and during their careers? and prejudice as to preferences and behaviour. Three examples in economics can illustrate this bias. First, Huberman (2001), inspired by Merton HENRIËTTE n 1993, Hein Schreuder argued in ESB that (1987), explains the investor home bias as ‘familiarity’: PRAST in economics the difference between men and people more often opt for shares in companies that are Professor at Tilburg women would automatically disappear: the literally or figuratively close to home. As a consequence, University and number of female students was increasing, and not only do they diversify their financial capital insuf- member of the ‘fromI low to high’ this would result in more female doc- ficiently, they also place too many eggs in the basket in Senate for D66 toral students and academic staff. Eline van der Heijden which their human capital is invested. Secondly, in a (1993) had her doubts about this, and enumerated the Harvard Business Case, Avery (2012) shows that Coca structural obstacles that women faced when choosing Cola misjudged the use of the word Diet in Diet Coke: economics and making a career in it. men did not buy it, because the word ‘diet’ evokes a Ten years later Aart Jan de Geus, the Minister of realm unbefitting to the stereotypical man. -

The Way Forward for Coalitions of Workers and Businesses for Sustainability

Herman Wijffels, The Netherlands. A thematic essay on encouraging solidarity The Way Forward for Coalitions of Workers and Businesses for Sustainability Herman H.F. Wijffels is Chairman of the Nether- Society nowadays expects more from both business and trade lands Social and Economic Council. In 1981, he unions in terms of corporate citizenship. Citizens and interest joined the Executive Board of the Rabobank groups increasingly hold companies directly accountable for S R Group, a financial institution headquartered in their social responsibilities. Public acceptance and a good repu- E K A M the Netherlands and active internationally in tation are important conditions for the continuation of many A R K A financing agri-business. In 1986 he was companies. The need for public acceptance is expressed in A J S © appointed as its Chairman. From 1968 until 1977, terms of a “license to operate,” which must be earned and he was a civil servant at the European Commission and in the Dutch renewed from time to time. administration. From 1977 until 1981, he was Secretary General of the Dutch Federation of Industries. Wijffels is also Chairman of the Society In my view, a modern company is a co-operation of a number of for Preservation of Nature in the Netherlands. He is Chairman of the different stakeholders.2 One of the conditions for the proper Supervisory Boards of the Rijksmuseum, Tilburg University, and the functioning of such a partnership model is the ability to maintain University Medical Centre Utrecht. Wijffels serves on a number of a certain balance in the degree of control and influence exer- corporate boards and as a director of several charities. -

Economisch Statistische Berichten Dossier

Economisch Statistische Berichten Dossier SINCE 1916 ISSUE 4767S - 1 NOVEMBER 2018 - VOLUME 103 WOMEN IN ECONOMICS Composed by the ESB editors and made possible by financial support from the Dutch economics and business faculties ESB Preface Preface ESB Women in economics or a way too long time, Finkelstein and Carmen Rein- economics has had a hart. I dare predict that some of shameful reputation them will win a Nobel prize in Fwhen it comes to the role of the future. ‘women in economics’. Female Many economics departments staff and female professors have are acutely aware of the under- been, and still are, very much representation of females among underrepresented, even when their staff. In recent years,hiring taking into account their lower rates of female assistant and enrolment rates in BA, MA and associate professors have risen. PhD programmes. Over time, they will be promot- A highly competitive academic ed to the ranks of full professor culture may have deterred and gender gaps will gradually females from entering the pro- be reduced. fession. Economists generally BAS JACOBS In the Netherlands, more and adhere to the idea that com- Professor at the Erasmus University more female economists are pre- petition is a good thing, and is Rotterdam and President of the Royal sent in economic policy and the necessary to foster academic Netherlands Economics Association public arena. Think of Barbara progress. Moreover, extreme Baarsma, Marieke Blom, Laura specialization allows researchers to exploit their com- van Geest, Sandra Phlippen, Mirjam van Praag, Esther- parative advantages. Economists take great pride in Mirjam Sent, Sheila Sitalsing, Marike Stellinga, just to publishing in the best economics journals. -

G7 Leaders Should End Not Just Coal, but Also Oil and Gas Finance in 2021

G7 Leaders should end not just coal, but also oil and gas finance in 2021 On June 11-13, World Leaders will gather at the G7 summit. There, they plan to adopt an agenda to “build back better from coronavirus and create a greener, more prosperous future”. We, the undersigned economists, believe that this means decisively shifting finance out of fossil fuels, and into clean alternatives worldwide. We welcome the decision taken last month by G7 Environment Ministers to end international finance to coal-fired power in 2021. We call on G7 Leaders to go further and shift their finance out of all fossil fuels in 2021. According to the IEA’s recent Net Zero scenario, which gives a 50% chance to limit global warming to 1.5°C, “there is no need for investments in new fossil fuel supply beyond 2021”. This applies not only to coal, but also oil and gas. Research co-authored by the UN Environment Programme shows that oil and gas production needs to decline by about 4% and 3% respectively every year between 2020 and 2030. Even if coal were phased-out overnight, the emissions from oil and gas fields already under development would push the world beyond 1.5°C, into catastrophic climate change. Due to carbon lock-in and path dependency, further investments in oil and gas would undermine achievement of the Paris Agreement’s goals. Continued investments in fossil fuel infrastructure create increased risks of stranded assets, unfunded clean-up, job cuts, and shortfalls in government revenue, as competition with cheaper and cleaner alternatives grows and demand for fossil fuels declines. -

Open Letter to Christine Lagarde

“The ECB must act now on climate change” Open letter to Christine Lagarde November 28th, 2019 Dear Christine Lagarde, As the new President of the European Central Bank you’ll face many challenges in the years to come, but the most crucial one is to determine how the ECB will act to fight climate change and accelerate the transition towards a carbon-neutral economy. During your hearing at the European Parliament, you rightly pledged to make sure the ECB puts the “protection of the environment at the core of the understanding of its mission.” As academics, civil society and trade union leaders, entrepreneurs and citizens deeply concerned by climate change, we believe that the most powerful financial institution in Europe cannot just sit passively as we witness a growing environmental crisis. Climate change not only imperils life-sustaining processes, it also threatens the financial stability, real economy and jobs. It has been estimated that without mitigation efforts, physical risks related to climate change could result in losses of up to $24 trillion of the value of global financial assets1. For all those reasons, we need a massive shift of financial flows towards a low carbon and socially just transition, and this can hardly be done without central banks actively pushing the financial system in the right direction. This will not only make our economy more sustainable but it will facilitate job creation in less carbon-intensive sectors. We know that this issue is being discussed among many central banks which are members of the “Network for Greening the Financial System”, including the ECB. -

Curriculum Vitae

Tim Haarlemmer Sint-Jacobstraat 101, 3011DK Rotterdam |15 february 1989 +316-12960246 | [email protected] | www.timhaarlemmer.nl SUMMARY Multidisciplinary and creative Quick learner and adapter Entrepreneurial and communicative Heart for sustainability and education EDUCATION 2013-2014 ICLON Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching: Educational Master 2010-2011: MScBA Global Business and Stakeholder Management RSM (Erasmus University) Cum Laude (GPA: 8,7/10) 2008-2010: Honours Programme Tilburg University (GPA: 8,4/10) 2007-2010: Minor Philosophy Tilburg University (GPA: 8,1/10) 2007-2010: BSc. Bachelor International Business Administration, Tilburg University: Cum Laude (GPA 8/10). Awarded with the Excellence Scholarship (for the top 3% of Tilburg’s students) WORK EXPERIENCE 2013-present Trainee ‘Eerst de Klas’ Traineeship in education, developed by a partnership between business, government and education. The trainee teaches three days a week, follows a master in education (Leiden University for me), gets trainings and does projects in sustainability for major Businesses. I teach Economics, Management and Philosophy. I also design my own course on management and economics and I train students in debating. 2008-present: Self employed Projects as business analyst - Project in external analysis, strategic alignment, business plans, e-commerce, CSR, competition, market analysis, strategic positioning, on average 4 months per project - Clients such as Aim for the Moon, Ordina N.V., MVO Loont, Jos Hofkens HIG, van Tilburg Bastianen, Nudge, Airbase Eindhoven, D&F Consulting Communication projects - Lecturer presentation skills Tilburg University and Leiden University - Interviewer - Host - Clients such as Tilburg University, Leiden University, Simon Stevin at Eindhoven University, Rotterdam School of Management, TEDxHaarlem, GroenLinks, HYPE, ROC and several environmental organizations.