Miami University - the Graduate School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

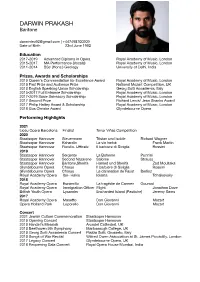

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

Kierkegaard and Byron: Disability, Irony, and the Undead

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2015 Kierkegaard And Byron: Disability, Irony, And The Undead Troy Wellington Smith University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Troy Wellington, "Kierkegaard And Byron: Disability, Irony, And The Undead" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 540. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/540 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIERKEGAARD AND BYRON: DISABILITY, IRONY, AND THE UNDEAD A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by TROY WELLINGTON SMITH May 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Troy Wellington Smith ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT After enumerating the implicit and explicit references to Lord Byron in the corpus of Søren Kierkegaard, chapter 1, “Kierkegaard and Byron,” provides a historical backdrop by surveying the influence of Byron and Byronism on the literary circles of Golden Age Copenhagen. Chapter 2, “Disability,” theorizes that Kierkegaard later spurned Byron as a hedonistic “cripple” because of the metonymy between him and his (i.e., Kierkegaard’s) enemy Peder Ludvig Møller. Møller was an editor at The Corsair, the disreputable satirical newspaper that mocked Kierkegaard’s disability in a series of caricatures. As a poet, critic, and eroticist, Møller was eminently Byronic, and both he and Byron had served as models for the titular character of Kierkegaard’s “The Seducer’s Diary.” Chapter 3, “Irony,” claims that Kierkegaard felt a Bloomian anxiety of Byron’s influence. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

Edward Rochester: a New Byronic Hero Marybeth Forina

Undergraduate Review Volume 10 Article 19 2014 Edward Rochester: A New Byronic Hero Marybeth Forina Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Forina, Marybeth (2014). Edward Rochester: A New Byronic Hero. Undergraduate Review, 10, 85-88. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol10/iss1/19 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2014 Marybeth Forina Edward Rochester: A New Byronic Hero MARYBETH FORINA Marybeth Forina is a n her novel Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë established several elements that are senior who is double still components of many modern novels, including a working, plain female hero, a depiction of the hero’s childhood, and a new awareness of sexuality. majoring in Elementary Alongside these new elements, Brontë also engineered a new type of male hero Education and English Iin Edward Rochester. As Jane is written as a plain female hero with average looks, with a minor in Rochester is her plain male hero counterpart. Although Brontë depicts Rochester as a severe, yet appealing hero, embodying the characteristics associated with Byron’s Mathematics. This essay began as a heroes, she nevertheless slightly alters those characteristics. Brontë characterizes research paper in her senior seminar, Rochester as a Byronic hero, but alters his characterization through repentance to The Changing Female Hero, with Dr. create a new type of character: the repentant Byronic hero. Evelyn Pezzulich (English), and was The Byronic Hero, a character type based on Lord Byron’s own characters, is later revised under the mentorship of typically identified by unflattering albeit alluring features and an arrogant al- Dr. -

Bibliography of Cooperatives and Cooperative Development

Bibliography of Cooperatives and Cooperative Development Compiled by the following Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs personnel: Original, 1999 Christopher D. Merrett, PhD, IIRA director and professor Norman Walzer, PhD, professor of Economics and IIRA director emeritus Update, 2007 Cynthia Struthers, PhD, associate professor, Housing/Rural Sociology Program Erin Orwig, MBA, faculty assistant, Value-Added Rural Development/Cooperative Development Roger Brown, MBA, manager, Value-Added Rural Development/Cooperative Development Mathew Zullo, graduate assistant Ryan Light, graduate assistant Jeffrey Nemeth, graduate assistant S. Robert Wood, graduate assistant Update, 2012 Kara Garten, graduate assistant John Ceglarek, graduate assistant Tristan Honn, research assistant Published by Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs Stipes Hall 518 Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 [email protected] www.IIRA.org This publication is available from IIRA in print and on the IIRA website. Quoting from these materials for noncommercial purposes is permitted provided proper credit is given. First Printing: September 1999 Second Printing: September 2007 Third Printing: June 2012 Printed on recycled paper Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................1 II. Theory and History of Cooperatives ....................................................................................................3 III. Governance, -

Michael Byron Michael Byron

Michael Byron 329 Belt Avenue, Apt. 301 St. Louis, Missouri 63112 314/935-6683 (w) 314/367-1146 (h) Current Position Professor of Art Washington University School of Art, St. Louis, Missouri Education Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, BFA. Nova Scotia College of Art & Design, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, MFA. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2007 The Suburban, “Main St. 02879”, Oak Park, IL. May-August. 2004 Galerie Delta Rotterdam, “Walpergisnacht”, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, June. Philip Slein Gallery, “A Decade of Work on Paper”, St. Louis, Missouri. October -November. 2002 Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston “Amitin Notebook Project”, June - September. Susan Inglett, “ Amitin Notebook Outtakes”, New York, New York, September19 - October 26. 2001 Rhodes College, “A Survey of the Grisaille Series, 1997-2000,” curated by Marina Pacini, Memphis, Tennessee, February - April. Elliot Smith Contemporary Art, “A Survey of the Grisaille Series, 1997-2000”, St. Louis, Missouri, April - May. Forum for Contemporary Art, “Amitin Notebook Project”, November 2001 - January 2002 (catalog). 2000 Carrie Seecrist Gallery, Chicago, Illinois, February-March. 1999 Baron/Boisante Gallery, “Portraits of Objects,” New York, New York; February-April. Schmidt Contemporary Art, “Drawings From a Blind Man’s Pencil,” St. Louis, Missouri, April. Elias Fine Art, Alliston, Massachusetts, November-December. 1998 Schmidt Contemporary Art, St. Louis, Missouri, February-March. 1997 Flatlands Galerie, Utrecht, The Netherlands, January-March. 1996 St. Louis Art Museum, “Currents 66”, St. Louis, Missouri. 1995 Olin Gallery, “Michael Byron, Short Stories, Paintings, 1993-1995”, Roanoke College, Salem, Virginia. Baron/Boisante Gallery, “Works on Paper, 1982-1995”, New York, New York. -

GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON: a Literary-Biographical-Critical

1 GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON: A literary-biographical-critical database 2: by year CODE: From National Library in Taiwan UDD: unpublished doctoral dissertation Books and Articles Referring to Byron, by year 1813-1824: Anon. A Sermon on the Death of Byron, by a Layman —— Lines on the departure of a great poet from this country, 1816 —— An Address to the Rt. Hon. Lord Byron, with an opinion on some of his writings, 1817 —— The radical triumvirate, or, infidel Paine, Lord Byron, and Surgeon Lawrenge … A Letter to John Bull, from a Oxonian resident in London, 1820 —— A letter to the Rt. Hon. Lord Byron, protesting against the immolation of Gray, Cowper and Campbell, at the shrine of Pope, The Pamphleteer Vol 8, 1821 —— Lord Byron’s Plagiarisms, Gentleman’s Magazine, April 1821; Lord Byron Defended from a Charge of Plagiarism, ibid —— Plagiarisms of Lord Byron Detected, Monthly Magazine, August 1821, September 1821 —— A letter of expostulation to Lord Byron, on his present pursuits; with animadversions on his writings and absence from his country in the hour of danger, 1822 —— Uriel, a poetical address to Lord Byron, written on the continent, 1822 —— Lord Byron’s Residence in Greece, Westminster Review July 1824 —— Full Particulars of the much lamented Death of Lord Byron, with a Sketch of his Life, Character and Manners, London 1824 —— Robert Burns and Lord Byron, London Magazine X, August 1824 —— A sermon on the death of Lord Byron, by a Layman, 1824 Barker, Miss. Lines addressed to a noble lord; – his Lordship will know why, – by one of the small fry of the Lakes 1815 Belloc, Louise Swanton. -

Gcrcbooks 4.Xls Page 1 of 5 15:58 on 22/06/2012 D19 the Cambridge Modern History Volume 02

This is a list of mostly history books from the library of Gervas Clay, who died 18 th April 2009 ( www.spanglefish.com/gervasclay ). Most of them have his bookplate; few have a dust cover. In general they are in good condition, though many covers are faded. Most are hardback; many are first editions. There is another catalogue of his modern books (mostly fiction) which you will find as a WORD document called "Books.doc" in the For Sale section of the Library at http://www.spanglefish.com/gervasclay/library.asp Alas! Though we have only read a few of these, and would love to read more, we just do not have the time. Nor do we have the space to store them. So all of these are BOOKS FOR SALE Box Title Author Publisher Original Publisher Date Edition Comment The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 1 Cambridge UP 1934 Vols. 1 to 10 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 4 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 5 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 6 D24 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 7 D23 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 8 D23 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 9 D25 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 10 D24 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 11 D25 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 12 D22 Queen Victoria Roger Pulford Collins 1951 No. 2 D21 The Age of Catherine de Medici J.E. Neale Jonathan Cape 1943 1st Edition D22 The two Marshalls, Bezaine & Petain Philip Guedalla Hodder & Stoughton 1943 1st Edition D22 Napoleon and his Marshalls A.G. -

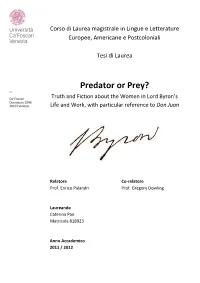

Predator Or Prey? Truth and Fiction About the Women in Lord Byron’S Life and Work, with Particular Reference to Don Juan

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Tesi di Laurea Predator or Prey? Truth and Fiction about the Women in Lord Byron’s Life and Work, with particular reference to Don Juan Relatore Co-relatore Prof. Enrico Palandri Prof. Gregory Dowling Laureanda Caterina Pan Matricola 818923 Anno Accademico 2011 / 2012 To my family Contents Introduction 9 1. The Discovery of Europe through the Grand Tour 12 2. English women 18 2.1. Lady Blessington’s Conversations of Lord Byron 18 2.2. Annabella Milbanke 22 2.3. Catherine Gordon Byron and Augusta Leigh 29 2.4. Aristocratic ladies – Lady Oxford, Lady Melbourne and Caroline Lamb 38 2.5. Claire Clairmont and the Shelleys 46 3. Libertinism in the eighteenth century 52 3.1. Marriage and Libertinism between England, Italy and Europe 52 3.2. The case of Byron 57 4. Italian women 61 4.1. Venice 61 4.2. Comparing Italian and English women 64 4.3. Marianna Segati 69 4.4. Margherita Cogni – La Fornarina 73 4.5. Teresa Gamba, Countess Guiccioli 77 5. Byron’s life and women in Don Juan – the ‘truth in masquerade’ 84 5.1. A comedy, mock-heroic epic and moral autobiographic poem 84 5.2. Venice – Muse and Mask 88 5.3. Truth and Fiction 93 5.4. A “new” Don Juan 97 5.5. Literary tradition VS autobiography – The journey of narrator and protagonist 101 5.6. Literary tradition VS autobiography – The “weaker” sex 106 5.7. Byron’s translation of the women around him in Don Juan 111 5.8. -

Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley's Limited

CHAPITRE DE LIVRE « Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley’s Limited Freedom in ‘‘Frankenstein’’ and ‘‘The Last Man’’ » Michael E. Sinatra dans Mary Shelley's Fictions: From Frankenstein to Falkner, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 95-108. Pour citer ce chapitre : SINATRA, Michael E., « Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley’s Limited Freedom in ‘‘Frankenstein’’ and ‘‘The Last Man’’ », dans Michael E. Sinatra (dir.), Mary Shelley's Fictions: From Frankenstein to Falkner, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 95-108. 94 Gender cal means of achievement ... Castruccio will unite in himself the lion and the fox'. 13. Anne Mellor in Ruoff, p. 284. 6 14. Shelley read the first in May and the second in June 1820. She also read Julie, 011 la Nouvelle Héloïse (1761) for the third time in February 1820, Gender, Authorship and Male having previously read it in 1815 and 1817. A long tradition of educated female poets, novelists, and dramatists of sensibility extending back to Domination: Mary Shelley's Charlotte Smith and Hannah Cowley in the 1780s also lies behind the figure of the rational, feeling female in Shelley, who read Smith in 1816 limited Freedom in Frankenstein and 1818 (MWS/ 1, pp. 318-20, Il, pp. 670, 676). 15. On the entrenchment of 'conservative nostalgia for a Burkean mode] of a and The Last Man naturally evolving organic society' in the 1820s, see Clemit, The Godwinian Novel, p. 177; and Elie Halévy, The Liberal Awakening, 1815-1830, trans. E. Michael Eberle-Sinatra 1. Watkin (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1961) pp. 128-32. -

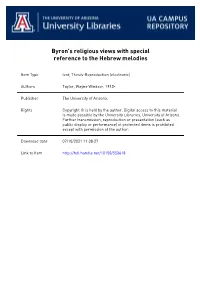

Director of Thesis Date Bfi a R E 9 7 9

Byron's religious views with special reference to the Hebrew melodies Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Taylor, Wayne Windsor, 1913- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 11:38:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553618 Byron's Religious Views with Special Reference to the Hebrew elodiea ty Tayne W« Taylor A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College University of Arizona 1942 Approved: lcM 2_ Director of Thesis Date Bfi A R E 9 7 9 / 3*! Z- To Dr* Melvin T* Solve whose original suggestion and subsequent advice made this study possible TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Pager- I. IntrodMtlon • . ......... ... 1 II. The . » . • 4 III. The Sources . • . * . * . 9 IV. The Hebrew Element . * . • • . • .... • * ... 54 V. The Christian Element • • • .... ... * 44 VI. The Calvinistic Element • . > . 50 VII. Cenelusion . * * . * * . • . 61 Bibliography . .... » , ... ... * , ' _ 66 \ 1 Chapter I Introduction The Hebrew Melodieo form part of the key which opens the door to Byron’s religious,beliefs. Most of these songs were Inspired by Byron’s reading and deep appreciation of the Bible. The purpose here is to point out what sections of the Bible were used as subject material for the Melodies and to indicate the great influence of Biblical teachings on Byron’s life and religious opinions. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing theUMI World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Order Number 8803923 Throwing the scabbard away: Byron’s battle against the censors o f Don Juan Blann, Troy Robinson, Jr., D.A. Middle Tennessee State University, 1987 Copyright ©1988 by Blann, Troy Robinson, Jr.