A Sustainable Economic Transition for Berau, East Kalimantan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Peminat Dan Terima Di Universitas Mulawarman

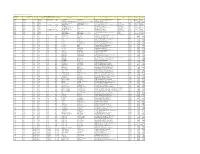

DATA PEMINAT DAN TERIMA DI UNIVERSITAS MULAWARMAN JALUR SNMPTN 2020 PEMINAT PEMINAT Nama Provinsi Nama Kota NAMA SEKOLAH LULUS PL1 LULUS PL2 JML LULUS PL1 PL2 Kalimantan Timur Kab Berau MAN BERAU 20 4 15 4 SMA IT ASH SHOHWAH 1 SMA NEGERI 12 BERAU 26 8 25 1 9 SMAN 1 BERAU 33 13 28 13 SMAN 10 BERAU 1 1 SMAN 11 BERAU 6 1 6 1 SMAN 13 BERAU 3 1 SMAN 14 BERAU 1 1 SMAN 2 BERAU 37 8 33 8 SMAN 3 BERAU 20 5 18 1 6 SMAN 4 BERAU 28 7 21 2 9 SMAN 5 BERAU 17 2 9 1 3 SMAN 6 BERAU 14 1 12 1 SMAN 7 BERAU 28 6 19 6 SMAN 8 BERAU 37 8 34 1 9 SMAS MUHAMADIYAH TANJUNG REDEB 2 2 SMAS PGRI 13 TANJUNG REDEB 15 2 11 2 SMK NEGERI 8 BERAU 8 3 6 3 SMKN 1 BERAU 12 11 SMKN 2 BERAU 4 1 2 1 2 SMKN 6 BERAU 2 2 Kab Berau Total 315 69 257 7 76 Kab Kutai Barat MAN KUTAI BARAT 6 1 5 1 SMAN 1 BENTIAN BESAR 2 1 SMAN 1 BONGAN 6 5 SMAN 1 JEMPANG 6 1 4 1 SMAN 1 LINGGANG BIGUNG 39 11 29 1 12 SMAN 1 LONG IRAM 11 2 11 2 SMAN 1 MUARA LAWA 11 2 10 2 SMAN 1 MUARA PAHU 5 1 5 1 PEMINAT PEMINAT Nama Provinsi Nama Kota NAMA SEKOLAH LULUS PL1 LULUS PL2 JML LULUS PL1 PL2 SMAN 1 PENYINGGAHAN 10 3 7 3 SMAN 1 SENDAWAR 47 15 34 1 16 SMAN 1 SILUQ NGURAI 4 3 SMAN 2 SENDAWAR 19 10 15 10 SMAN 3 SENDAWAR 6 1 4 1 SMKN 1 SENDAWAR 16 5 16 5 SMKN 2 SENDAWAR 8 1 6 1 Kab Kutai Barat Total 196 53 155 2 55 Kab Kutai Kartanegara MA DDI KARYA BARU LOA JANAN 6 1 6 1 MA Negeri 1 Kutai Kartanegara 13 3 12 3 MAN 2 KUTAI KARTANEGARA 70 20 57 20 MAS AS ADIYAH SANTAN TENGAH 6 2 6 2 MAS MIFTAHUL ULUM ANGGANA 18 5 18 5 SMA AL HAYAT SAMBOJA 1 1 SMA ISLAM ULUMUDDIN SAMBOJA 2 1 2 1 SMA IT NURUL ILMI TENGGARONG 10 1 9 1 -

Arahan Pengendalian Konversi Hutan Menjadi Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Di Kabupaten Paser, Kalimantan Timur

CONTROLLING DIRECTION OF FOREST CONVERSION INTO OIL PALM PLANTATION IN PASER REGENCY, EAST KALIMANTAN PROVINCE Tantie Yulandhika 3608.100.069 [email protected] SEPULUH NOPEMBER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SURABAYA 2012 Problem Formulation, Research Purpose & Goals Problem Formulation Land use in Paser Regency undergone significant changes, especially on land uses of forest that changes into oil palm plantation Question of Research: “How is the controlling direction of forest conversion into oil palm plantation in Paser Regency?” Research Purpose Compossing the controlling direction of forest conversion into oil palm plantation in Paser Regency G o Analysis the characteristic of forest conversion into oil palm plantation in Paser o Regency Analysis of typology area a o o Analysis the causing factors of forest conversion into oil palm plantation in Paser l Regency s o Compossing the controlling direction of forest conversion into oil palm plantation in Paser Regency Scope of Research Study Area Discussion Scope of discussions in this research are forest conversion into oil palm plantation Substance Scope of substances in this research including: . Land Conversion Theory . Controlling Conversion Land Theory Benefits of Research THEORITICAL BENEFITS Improving knowledge especially in the aspect of land conversion in the forest area PRACTICAL BENEFITS Recommend the controlling direction of forest conversion into oil palm plantation in Paser Regency Research Area Overview Research Area Overview Placed on above 0-100 mdpl Land Uses Forest, -

The Kelay Punan in East Kalimantan

TROPICS Vol. r(213),pp. 143-153 Issued December, 1991 Changes ln Economic Life of the Hunters and Gatherers : the Kelay Punan in East Kalimantan Makoto INoun Faculty of Agriculnre, University of Tokyo, l-1-l Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113, Japan LucnN Faculty of reaching and Education, Mulawarman University, Kampus Gunung Kelua, Samarinda, Kalimantan Timur, Indonesia Icrn Bilung Tiopical Rain Forest Research Center, Mulawarman University, Kampus Gunung Kelua, Samarinda, Kalimantan Timur, Indonesia Abstract : The Punan people in Bomeo island had traded forest products for the necessities of life with the Dayak people, who traded them with the brokers. At present, the Kelay Punan people in East Kalimantan rade directly with the brokers and merchants, who control the rade of the forest products from the region. They are degraded to debtors now and still carrying out hunting and gathering to pay back the debt" Besides, the inroduction of swidden cultivation is one of the most important factors to affect their life style. Their swidden system might not be so sustainable, since they were not tradirional swidden cultivators like the Kenyah Dayak people. Key Words: East Kalimantan / Punan / swidden cultivation / trade The "Punan" is a generic term for hunters and gatherers living in Borneo island. The Punan people have the same physical characteristics as the Dayaks practicing swidden cultivation, since the Punans are also the protd-Malayan people. The bodies of the Punans, however, are generally better-built than those of the Dayaks. According to Hoffman (1983), Bock's description of the Punan (Bock, 1881) is one of the earliest to appear in print. -

The Physicochemistry of Stingless Bees Honey (Heterotrigona Itama) from Different Meliponiculure Areas in East Kalimantan, Indon

Advances in Biological Sciences Research, volume 11 Proceedings of the Joint Symposium on Tropical Studies (JSTS-19) The Physicochemistry of Stingless Bees Honey (Heterotrigona itama) from Different Meliponiculure Areas in East Kalimantan, Indonesia Suroto Hadi Saputra1,* Bernatal Saragih2 IrawanWijaya Kusuma3 Enos Tangke Arung4,* 1 Faculty of Forestry, Mulawarman University. Jl. Kuaro Samarinda 75119. P.O.Box 1068, East Kalimantan, Indonesia Tel. +62-541-749343 2 Faculty of Agriculture, Mulawarman University Jl. Pasir Belengkong 75119, East Kalimantan Indonesia Telp. +62- 541-738347 3 Faculty of Forestry, Mulawarman University. Jl. Kuaro Samarinda 75119. P.O.Box 1068, East Kalimantan, Indonesia Tel. +62-541-74934 4 Laboratory of Forest Product Chemistry Faculty of Forestry, Mulawarman University. Jl. Ki Hajar Dewantara Kampus Gunung Kelua, Samarinda 75116, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Tel./Fax.: +62-541-737081 *Corresponding author. Email:[email protected]; Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Almost all of the stingless honey bees in East Kalimantan are in the district/city. Various types of plants as sources of nectar in each region for stingless bees honey are interesting for research. This study’s purpose was the physicochemical analysis of H. itama honey from different meliponiculture areas in East Kalimantan. The data were analyzed using variance analysis at the 5% level and a further test of the smallest significant difference at the 5% level. The results showed that the physicochemistry of H. itama honey was the respondent’s response value to color 52-100%, aroma 74-92%, taste 56-88%, moisture content 30.80-33.67%, pH value 2.77-3,20, reducing sugar content 51.59-59.56%, sucrose content 1.82-3.82%, total dissolved solids content 67.23-69.77⁰Brix, ash content 0.17-0.35% and heavy metals were not detectable-0.01 mg / L). -

Design of the Narrative Structure of Berau Natural Tourism Promotional Video Using Freytag’S Pyramid Method

Design of The Narrative Structure of Berau Natural Tourism Promotional Video using Freytag’s Pyramid Method Sonia Winner Nursalim1 and Alfiansyah Zulkarnain2 1,2Visual Communication Design Department, Faculty of Design, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Jl. MH. Thamrin Boulevard Lippo Village 1100, Tangerang 15810, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Indonesia’s tourism potential is quite large. But in fact, tourism is still very centralized in only a few places such as Java and Bali. Even though, there are still a lot of tourist attractions that are no less interesting and beautiful, like the natural tourism of Berau Regency, which is located in East Kalimantan. Therefore, in designing this video, it is necessary to divide the narrative which is dissected using Freytag’s Pyramid narrative structure method. The research methodology used is to use qualitative methods by conducting expert interview studies that are expected to provide valid information. The divided narrative of this promotional video will be useful in the process of designing a visual study. Keywords. Freytag’s Pyramid, Tourism Promotional Video, Berau, Narrative Structure. 1. Introduction Indonesia relies on great potential in its tourism sector as a source of foreign exchange [6]. Unfortunately, according to the Tourist Market Data Study [8], the most frequently visited tourist destinations from all over Indonesia are Java and Bali. Therefore, it is necessary to have a promotional video that can introduce other tourist destinations. For example, natural tourism in Berau Regency, East Kalimantan can be made in a structured narrative and visually attractive. In this promotional video, Lana is for the title and also the name of the character. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

CAIPSDCC Policy Brief

Lifting climate action through COVID-19 recovery Virtual CAIPSDCC High-level Dialogue 24 August 2020 POLICY BRIEF CONTENTS Introduction The devastating and unprecedented impact of the Introduction 1 COVID-19 pandemic underscores the urgency for global cooperation to address complex social, Reframing the task: economic and environmental challenges that underpin From challenge to opportunity 2 human and planetary wellbeing into the future. Pathways towards cooperation 4 Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne observed in June 2020 that, “COVID-19 is a shared crisis – a Conclusion 7 reminder that many problems are best solved or, indeed, can only be solved through cooperation. At Notes 8 the heart of successful international cooperation is the concept that each country shares, rather than yields, a portion of its sovereign decision-making. And in return, each gets something from it that is greater than their contribution.”1 ABOUT THE GRIFFITH ASIA INSTITUTE Cooperation is by no means assured. Ongoing border closures, travel restrictions and cities in lockdown The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally have amplified the isolationist tendencies of some recognised research centre in the Griffith Business nations, while exposing the fragility of regional and School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding global multilateral institutions. As governments shift commitment and future aspirations for the study of between COVID-19 ‘response’ and ‘recovery’ modes, and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. new challenges and barriers to cooperation continue At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice to emerge. leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific—cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and Yet, when viewed through a strategic lens, COVID-19 connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s offers the opportunity to lift global collaborative Asia-Pacific future. -

Journal of Physical Education and Sports Certification Impact on Performance of PESH Teachers in State Junior High Schools in Pa

Journal of Physical Education and Sports 10 (2) (2021) : 123-128 https://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/jpes Certification Impact on Performance of PESH Teachers in State Junior High Schools in Paser Regency, East Kalimantan Province Adithya Soeprayogie , Endang Sri Hanani, Bambang Priyono Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia Article Info Abstract ________________ ___________________________________________________________________ History Articles This research is motivated by issuing the National Education System Law and Received: the Lecturer Teacher Law regulating the teacher certification program, which 22 March 2021 allegedly impacts teacher performance to be more professional. This type of Accepted: research is qualitative research to produce spoken or written words. Data 16 April 2021 collection by observation, interviews and documentation. Primary data were Published: 30 June 2021 10 certified Physical Education, Sport and Health (PESH) teachers, while ________________ secondary data resulted from observations, questionnaires, PTK, certificates Keywords: and lesson plans. Naturalistic data analysis according to actual situations in the Certification, field. The results showed the performance of most 10 certified PESH teachers, Performance, Teacher with 4 competencies indicators still need improvement on 2 competencies, Competence namely Pedagogic and Professional. Meanwhile, Personality and Social ____________________ competences are in good category. Factors affecting performance based on normative commitment need to be improved, while the physical work environment conditions need improvement in school facilities, infrastructure and facilities. The welfare conditions of the 10 PESH teachers were categorized as quite prosperous financially. The conclusion of this research requires several inputs, including: PESH teachers should prepare lesson plans according to the conditions of each school. PESH teachers make scientific papers without waiting for promotion and archive properly. -

The Heart of Coral Triangle

The Heart of Coral Triangle © Cipto Aji Gunawan / WWF-Indonesia Berau, easT kalimanTan Its central location within the whole Coral Triangle region makes its suitable for Home of the 444 Berau to relate itself as the most ‘vital’ organ in the Coral Triangle body. The proposition will be hard to argue when considering the regency, passed by two hermatypic corals important rivers in Borneo island, Segah and Kelay, is home for the 444 species of hermatypic corals species (the second largest after Raja Ampat), 8 seagrass (second largest species, 872 reef fish and 9 cetaceans. It is also the foraging and nesting ground after Raja Ampat), of 2 out of 6 marine turtle species found in Indonesia, green turtle (Chelonia mydas) and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata). Not to mention the famous saltwater lake, 8 seagrass species, Kakaban in Derawan islands, inhabited by the very unique 4 endemic jellyfish 872 reef fish and 9 species. cetaceans. It is also As much as 164.501 people inhabited the regency according to statistic from 2007 the foraging and with 41,16% of them living in the coastal sub-district. Berau’s primary income mostly comes from mining and forests exploitation. Coal mine is the priority source nesting ground of 2 of income for Berau while many forests in the area have been converted into palm out of 6 marine turtle oil plantations. And although tourism has become another source of income for the region, it is still lacking a proper management. The region’s management and species found in utilization of its local income are still very much oriented to terrestrial usage than to marine and coastal zone management. -

Social Capital As the Foundation of the Integrated Independent Development

Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal Volume 27, Special Issue 2, 2021 SOCIAL CAPITAL AS THE FOUNDATION OF THE INTEGRATED INDEPENDENT DEVELOPMENT Teddy Febrian, Merdeka Malang University I Made Weni, Merdeka Malang University Praptining Sukowati, Merdeka Malang University ABSTRACT Social capital is a determinant for unequal regional development and is needed in human, social, economic, and political fields. The capital, such as trust, social networks, and community norms or values has advanced to include factors that have direct and important impacts on regional development. Therefore, this study analyzes social capital as a basis for development in Sangatta city, East Kutai Regency, and also identifies the supporting and inhibiting factors. A qualitative descriptive method was used to collect information about real and current situations, which were then analyzed according to Moleong’s technique that focused on field processes. The results showed that public trust in regional development displayed strong support in terms of facilities, education, and health. Also, the norms or values in society were formed from diverse ethnic groups, religions, and regional origins. Therefore, the complexity of forming social networks based on kinship and common political views has an impact on efforts to support or hinder regional development. The supporting factor for regional development in North Sangatta is that the area is a center for offices, government, and the economy. It is also the main location in East Kutai to attain work or business opportunities. Meanwhile, the inhibiting factors were limited budgets, population, and the suboptimal implementation of regional regulations. Consequently, these factors are the realities experienced in making social capital a basis for regional development in Sangatta city. -

The Worthiness' Analysis of the Tempe Industry in Suliliranbaru Village, District Paserbelengkong, Paser Regency

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 15, Issue 7 Ser. II (July 2021), PP 01-04 www.iosrjournals.org The worthiness’ analysis of the Tempe Industry In SuliliranBaru Village, District PaserBelengkong, Paser Regency (A Case Research on Mr. Sutrisno's Tempe Home Industry) Noryun1, Yuli Setiowati2, Asman3 1 Muhammadiyah Agricultural Science College, Tanah Grogot 2 Muhammadiyah Agricultural Science College, Tanah Grogot 2 Muhammadiyah Agricultural Science College, Tanah Grogot Abstract The worthiness’ analysis of the Tempe Industry in Suliliran Baru Village, Paser Belengkong District, Paser Regency (Case Research on the Tempe Home Industry Owned by Mr. Sutrisno. of this research aims to determine: To analyze the amount of business income of the tempe industry in Suliliran Baru Village, Paser Belengkong District, Paser Regency and To analyze the worthiness of the tempe industry in Suliliran Baru Village, Paser Belengkong District, Paser Regency. This research was conducted at the Tempe Home Industry owned by Mr. Sutrisno in Suliliran Village Baru Paser Belengkong Subdistrict. The business worthinessresearch method is design used in this research. The analysis used in this research is income analysis, R / C ratio analysis and BEP analysis. Theresearch results indicate that: (1) the income earned The Tempe Home Industry owned by Mr. Sutrisno, amounting to IDR6,074,307 in one month. This means that Mr. Sutrisno's Tempe Home Industry will get profit. (2) The resulting Return Cost Ratio is 1.14, the Home Industry will get a profit of 14. So the business owned by Mr. -

Financial Sustainability Dan Financial Performance Pemerintah Daerah Kabupaten/Kota Di Kalimantan Timur

Prosiding 4th Seminar Nasional Penelitian & Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat 2020 978-602-60766-9-4 FINANCIAL SUSTAINABILITY DAN FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE PEMERINTAH DAERAH KABUPATEN/KOTA DI KALIMANTAN TIMUR Muhammad Kadafi 1), Amirudin 2) 1) Dosen Jurusan Akuntansi Politeknik Negeri Samarinda, Samarinda 2) Dosen Jurusan Akuntansi Politeknik Negeri Samarinda, Samarinda ABSTRACT This study aims to determine and analyze Financial Sustainability, Trend Financial Sustainability, Map of Financial Performane and Financial Performance of district / city governments in East Kalimantan in 2015-2019. The benefit of this research is that it becomes input for district / city governments and provincial governments in making policies related to APBD.The analysis tool uses the calculation of financial sustainability, financial sustainability trends, metode quadrant, financial performance which consists of the calculation of growth, share, elasticity, index X, IKK. This study also maps the performance of the LGR based on the Quadrant Method. The results of this study indicate that there are 5 districts / cities that have financial sustainability above the average and 5 districts / cities whose values are below the average. For 5 years, Trend Financial Sustainability has grown, from a value of 40.77%, 36.45%, 29.07%. In 2018 it increased by a value of 47.34%, then in 2019 it decreased again by 36.72%. LGR performance map using the Quadrant Method, there are no districts / cities in East Kalimantan Province that are included in Quadrant 1 which is classified as ideal. In Quadrant 2 are East Kutai District, North Penajam Paser and Mahakam Hulu. The areas in this quadrant are considered not ideal. In Quadrant 3, there are three districts / cities, namely Balikpapan City, Berau Regency, Samarinda and Bontang.