Native Snakes of Rhode Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

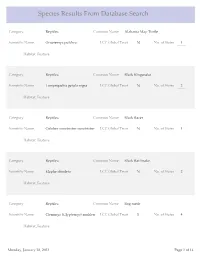

Species Results from Database Search

Species Results From Database Search Category Reptiles Common Name Alabama Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys pulchra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Kingsnake Scientific Name Lampropeltis getula nigra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Racer Scientific Name Coluber constrictor constrictor LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Rat Snake Scientific Name Elaphe obsoleta LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Bog turtle Scientific Name Clemmys (Glyptemys) muhlen LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 4 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 1 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Broadhead Skink Scientific Name Eumeces laticeps LCC Global Trust N No. of States 5 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Coal Skink Scientific Name Eumeces anthracinus LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 8 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Five-lined Skink Scientific Name Eumeces fasciatus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys geographica LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Musk Turtle Scientific Name Sternotherus odoratus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 2 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Common Ribbonsnake Scientific Name Thamnophis sauritus sauritus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Snapping Turtle Scientific Name Chelydra serpentina LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Corn snake Scientific Name Elaphe guttata guttata LCC Global Trust N No. -

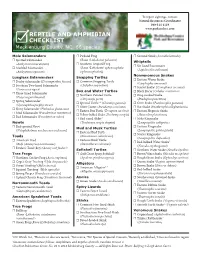

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

The Hognose Snake: a Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State 1977 The Hognose Snake: A Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years M. R. Voorhies University of Nebraska State Museum, [email protected] R. G. Corner University of Nebraska State Museum Harvey L. Gunderson University of Nebraska State Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Voorhies, M. R.; Corner, R. G.; and Gunderson, Harvey L., "The Hognose Snake: A Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years" (1977). Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum. 8. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. University of Nebraska State Museum and Planetarium 14th and U Sts. NUMBER 15JAN 12, 1977 ognose snake hunting in sand. The snake uses its shovel-like snout to loosen the soil. Hognose snakes spend most of their time above ground, but burrow in search of food, primarily toads. Even when toads are buried a foot or more in sand, hog nose snakes can detect them and dig them out. (Photos by Harvey L. Gunderson) Heterodon platyrhinos. The snout is used in digging; :tivities THE HOG NOSE SNAKE hognose snakes are expert burrowers, the western species being nicknamed the "prairie rooter" by Sand hills ranchers. The snakes burrow in pursuit of food which consists Prairie Survivor for almost entirely of toads, although occasionally frogs or small birds and mammals may be eaten. -

Copperhead & Endangered Species Agkistrodon Contortrix

Natural Heritage Copperhead & Endangered Species Agkistrodon contortrix Program State Status: Endangered www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife DESCRIPTION: Copperheads get their name due to their solid, relatively unmarked, coppery-colored head resembling the color of an old copper coin. As with all pit vipers, Copperheads have broad, triangularly shaped heads, with a distinct narrowing just behind the head. The eyes have vertically elliptical (catlike) pupils. There is a very thin line on each side of the face that separates the richer copper color of the top of the head from the lighter color of the lip area. The iris of the eye is pale gold, and the pupil is dark. On the body there is a series of dark brown to reddish, hourglass-shaped, cross bands. These are narrow in the middle of the body and broad to the sides. The ground color ranges from beige to tan. Body markings are continuous over the entire length of the body, including the tail. Young snakes are replicas of adults, except that the body has an overtone of light grey and the tip of the tail is yellow. Adult from Hampshire County; photo by Mike Jones/MassWildlife Adult Copperheads usually measure 60–90 cm (24–36 inches) in length; the newborn young are usually 18–23 ridge protrudes from the middle of each scale), giving cm (7–9 inches). Males usually have longer tails, but the snake a relatively rough-skinned appearance. females can grow to greater total lengths (up to 4 feet). There is no reliable external cue to differentiate the SIMILAR SPECIES IN MASSACHUSETTS: The sexes. -

Habitats Bottomland Forests; Interior Rivers and Streams; Mississippi River

hognose snake will excrete large amounts of foul- smelling waste material if picked up. Mating season occurs in April and May. The female deposits 15 to 25 eggs under rocks or in loose soil from late May to July. Hatching occurs in August or September. Habitats bottomland forests; interior rivers and streams; Mississippi River Iowa Status common; native Iowa Range southern two-thirds of Iowa Bibliography Iowa Department of Natural Resources. 2001. Biodiversity of Iowa: Aquatic Habitats CD-ROM. eastern hognose snake Heterodon platirhinos Kingdom: Animalia Division/Phylum: Chordata - vertebrates Class: Reptilia Order: Squamata Family: Colubridae Features The eastern hognose snake typically ranges from 20 to 33 inches long. Its snout is upturned with a ridge on the top. This snake may be yellow, brown, gray, olive, orange, or red. The back usually has dark blotches, but may be plain. A pair of large dark blotches is found behind the head. The underside of the tail is lighter than the belly. The scales are keeled (ridged). Its head shape is adapted for burrowing after hidden toads and it has elongated teeth used to puncture inflated toads so it can swallow them. Natural History The eastern hognose lives in areas with sandy or loose soil such as floodplains, old fields, woods, and hillsides. This snake eats toads and frogs. It is active in the day. It may overwinter in an abandoned small mammal burrow. It will flatten its head and neck, hiss, and inflate its body with air when disturbed, hence its nickname of “puff adder.” It also may vomit, flip over on its back, shudder a few times, and play dead. -

Eastern Milksnake,Lampropeltis Triangulum

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 61 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. Fischer, L. 2002. COSEWIC status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-29 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jonathan Choquette for writing the status report on the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum) in Canada. This report was prepared under contract with Environment Canada and was overseen by Jim Bogart, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Couleuvre tachetée (Lampropeltis triangulum) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Eastern Milksnake — Sketch of the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum). -

Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 78 Number 1-2 Article 11 1971 Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa J. J. Berberich University of Iowa C. H. Dodge University of Iowa G. E. Folk Jr. University of Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1971 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Berberich, J. J.; Dodge, C. H.; and Folk, G. E. Jr. (1971) "Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 78(1-2), 25-26. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol78/iss1/11 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Berberich et al.: Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in So 25 Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa J. J. BERBERICH,1 C. H. DODGE and G. E. FOLK, JR. J. J. BERBERICH, C. H . DODGE, & G. E. FOLK, JR. Overlapping ( Heterodon nasicus nasicus Baird and Girrard) is reported from of ranges of eastern and western hognose snakes in southeastern a sand prairie in Muscatine County, Iowa. Iowa. Proc. Iowa Acad. Sci., 78( 1 ) :25-26, 1971. INDEX DESCRIPTORS : hognose snake; Heterodon nasicus; H eterodon SYNOPSIS. -

AG-472-02 Snakes

Snakes Contents Intro ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 What are Snakes? ...............................................................1 Biology of Snakes ...............................................................1 Why are Snakes Important? ............................................1 People and Snakes ............................................................3 Where are Snakes? ............................................................1 Managing Snakes ...............................................................3 Family Colubridae ...............................................................................................................................................................................................5 Eastern Worm Snake—Harmless .................................5 Red-Bellied Water Snake—Harmless ....................... 11 Scarlet Snake—Harmless ................................................5 Banded Water Snake—Harmless ............................... 11 Black Racer—Harmless ....................................................5 Northern Water Snake—Harmless ............................12 Ring-Necked Snake—Harmless ....................................6 Brown Water Snake—Harmless .................................12 Mud Snake—Harmless ....................................................6 Rough Green Snake—Harmless .................................12 -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Venomous Nonvenomous Snakes of Florida

Venomous and nonvenomous Snakes of Florida PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEVIN ENGE Top to bottom: Black swamp snake; Eastern garter snake; Eastern mud snake; Eastern kingsnake Florida is home to more snakes than any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. Since only six species are venomous, and two of those reside only in the northern part of the state, any snake you encounter will most likely be nonvenomous. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission MyFWC.com Florida has an abundance of wildlife, Snakes flick their forked tongues to “taste” their surroundings. The tongue of this yellow rat snake including a wide variety of reptiles. takes particles from the air into the Jacobson’s This state has more snakes than organs in the roof of its mouth for identification. any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. They are found in every Fhabitat from coastal mangroves and salt marshes to freshwater wetlands and dry uplands. Some species even thrive in residential areas. Anyone in Florida might see a snake wherever they live or travel. Many people are frightened of or repulsed by snakes because of super- stition or folklore. In reality, snakes play an interesting and vital role K in Florida’s complex ecology. Many ENNETH L. species help reduce the populations of rodents and other pests. K Since only six of Florida’s resident RYSKO snake species are venomous and two of them reside only in the northern and reflective and are frequently iri- part of the state, any snake you en- descent. -

Reptiles and Amphibians of the Farm

AA guideguide toto thethe ReptilesReptiles andand AmphibiansAmphibians ofof UniversityUniversity FarmFarm Squire Valleevue and Valley Ridge Farms Case Western Reserve University Dr. Ana B. Locci, Director Prepared by Jacob R. G. Kribel, June 2005 ImportantImportant notesnotes onon thisthis guideguide ThisThis isis anan introductoryintroductory guideguide toto thethe reptilereptile andand amphibianamphibian speciesspecies ofof UniversityUniversity farm.farm. ItIt listslists thethe speciesspecies presentpresent oror possiblypossibly present,present, andand attemptsattempts toto provideprovide baselinebaseline informationinformation thatthat willwill bebe usefuluseful toto anyoneanyone wishingwishing toto learnlearn moremore aboutabout thethe reptilesreptiles && amphibiansamphibians foundfound here.here. TheThe physicalphysical descriptionsdescriptions areare ofof thethe mostmost commoncommon forms,forms, asas therethere isis variationvariation withinwithin somesome species.species. MakeMake suresure youyou havehave aa goodgood fieldfield guideguide inin handhand beforebefore settingsetting offoff toto discoverdiscover thethe reptilesreptiles && amphibiansamphibians ofof thethe farm!farm! ImportantImportant notesnotes onon thisthis guideguide ThroughoutThroughout thisthis guideguide youyou willwill findfind notesnotes onon thethe conservationconservation statusstatus ofof species,species, bothboth inin thethe statestate ofof OhioOhio andand worldwide.worldwide. Extirpated: A species that occurred in Ohio at the time of European settlement -

Snakes of New Jersey Brochure

Introduction Throughout history, no other group of animals has undergone and sur- Snakes: Descriptions, Pictures and 4. Corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata): vived such mass disdain. Today, in spite of the overwhelming common 24”-72”L. The corn snake is a ➣ Wash the bite with soap and water. Snakes have been around for over 100,000,000 years and despite the Range Maps state endangered species found odds, historically, 23 species of snakes existed in New Jersey. However, sense and the biological facts that attest to the snake’s value to our 1. Northern water snake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon): ➣ Immobilize the bitten area and keep it lower than your environment, a good portion of the general public still looks on the in the Pine Barrens of NJ. It heart. most herpetologists believe the non-venomous queen snake is now 22”-53”L. This is one of the most inhabits sandy, forested areas SNAKES OF extirpated (locally extinct) in New Jersey. 22 species of snakes can still snake as something to be feared, destroyed, or at best relegated to common snakes in NJ, inhabit- preferring pine-oak forest with be found in the most densely populated state in the country. Two of our glassed-in cages at zoos. ing freshwater streams, ponds, an understory of low brush. It ➣ lakes, swamps, marshes, and What not to do if bitten by a snake species are venomous, the timber rattlesnake and the northern All snakes can swim, but only the northern water snake and may also be found in hollow queen snake rely heavily on waterbodies.