Radio 4 Deighton File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuaderno-CCU-Mayo-Junio-18.Pdf

1 2 La noticia de la primera sesión del Cineclub de Granada Periódico “Ideal”, miércoles 2 de febrero de 1949. El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2017-2018, cumplimos 64 (68) años. 3 MAYO-JUNIO 2018 MAY-JUNE 2018 UN ROSTRO EN LA PANTALLA (V): A FACE ON THE SCREEN (V): MICHAEL CAINE (part 1: the 60’s) MICHAEL CAINE (1ª parte: los años 60) (celebrating Caine’s 85th birthday) (celebrando su 85 cumpleaños) Viernes 18 mayo / Friday 18th may 21 h. ZULÚ (1964) Cy Endfield ( ZULU ) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 22 mayo / Tuesday 22th may 21 h. IPCRESS (1965) Sidney J. Furie v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes25 mayo / Friday 25th may 21 h. ALFIE (1966) Lewis Gilbert v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 5 junio / Tuesday 5th june 21 h. LA CAJA DE LAS SORPRESAS (1966) Bryan Forbes ( THE WRONG BOX ) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 8 junio / Friday 8th june 21 h. FUNERAL EN BERLÍN (1966) Guy Hamilton ( FUNERAL IN BERLÍN ) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Todas las proyecciones en la Sala Máxima de la ANTIGUA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA (Av. de Madrid). Entrada libre hasta completar aforo All projections at the Assembly Hall in the Former Medical College (Av. de Madrid) Free admission up to full room 4 5 “ (…) Existen unos ocho kilometros de papel de periódico y al menos siete biografías que hablan de mí (Dios sabe por qué), así que ¿por qué añadir algo a todo ello? Quizá con objeto de que, para variar, el disco suene en mi propio tocadiscos. -

KEVIN KILLIAN / Bowering's Fragments

KEVIN KILLIAN / Bowering's Fragments You'd have to have a heart of stone to resist the amorous appeal of George Bowering's 1990 novel Harry's Fragments. An accomplished storyteller, Bowering surprised us yet again with this enigmatic, genre-bending blend of thriller and nouvelle vague. Throughout he plays the showman's ancient trick of never letting us see him sweat, combining a complex plot with a throwaway style, while finding room in the slim volume to evoke dozens of far-flung locations and many, many sexy women. What's that Bond movie with the most Bond girls in it? Harry's Fragments makes that one look like a sexless sort of William Wellman actioner. (Goldfinger and Thunderball tie with five apiece, but in comparison Harry's Fragments makes them seem like chaste all-male retreats set in Mount Athos in northern Greece.) The surplus of women in Harry's Fragments is perhaps a tip of the hat to Bond, or to Len Deighton's spy hero, Harry Palmer. Perhaps Harry Palmer or Harry Lime inspired the creation of Bowering's Harry, this mysterious traveler. I keep thinking he's Canadian, he's so critical of other nations, but I find that nowhere does the text actually say that Harry's a Canadian, though he lives in Vancouver certainly. No wait, in the last fifth of the book we are told that he is a "Canadian in a manner of speaking." His profession is similarly unclear, but we are told again and again he is neither a spy nor a writer, at least, not by nature. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

![[O95Y]⋙ SS-GB by Len Deighton #514EY7KMZRX #Free Read Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2202/o95y-ss-gb-by-len-deighton-514ey7kmzrx-free-read-online-762202.webp)

[O95Y]⋙ SS-GB by Len Deighton #514EY7KMZRX #Free Read Online

SS-GB Len Deighton Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically SS-GB Len Deighton SS-GB Len Deighton What if WWII went the other way? In this alternative-history novel, Deighton imagines a chilling world where British Command surrendered to the Nazis in 1941, Churchill has been shot, the King is in the dungeon, and the SS are in Whitehall. In occupied Britain, Scotland Yard conducts business as usual...only under the command of the SS. Detective Inspector Archer is assigned to what he believes is a routine murder case--until SS Standartenführer Huth arrives from Berlin with orders from Himmler himself to supervise the investigation. Soon, Archer finds himself caught in a high level, action-packed espionage battle. This is a spy story different from any other--one that only Deighton, with his flair for historical research and his narrative genius, could have written. Download SS-GB ...pdf Read Online SS-GB ...pdf Download and Read Free Online SS-GB Len Deighton From reader reviews: Inocencia Hensley: Do you have favorite book? For those who have, what is your favorite's book? Book is very important thing for us to learn everything in the world. Each book has different aim as well as goal; it means that book has different type. Some people experience enjoy to spend their time and energy to read a book. These are reading whatever they acquire because their hobby will be reading a book. How about the person who don't like studying a book? Sometime, particular person feel need book once they found difficult problem or exercise. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

The Cultures of the Suburbs International Research Network 2014 Conference: Imagining the Suburbs 19Th-21 June 2014 University of Exeter

The Cultures of the Suburbs International Research network 2014 Conference: Imagining the Suburbs 19th-21 June 2014 University of Exeter Spies in the Suburbs Bringing the Cold War to the suburbs: Re-locating the post-war conflict in Le Carre and Deighton Janice Morphet Visiting Professor, Bartlett School of Planning, University College London [email protected] The development and recognition of the Cold War as a major shift in world conflict from ‘over there’ where battle was conducted in uniforms by the armed services to one that was to be fought on the new home front through spies was a significant plot component in the first novels of both John Le Carre, ‘Call for the Dead’ (1961) (later filmed as The Deadly Affair) and Len Deighton’s ‘The Ipcress File’ (1962). In both novels, the sleepy suburban milieu becomes the centre of Cold War espionage discovered and resolved by two iconic outsider characters, George Smiley and Harry Palmer, introduced in these works. Smiley and Palmer were seemingly dissimilar in almost every way including their age, class and war records. However these characters were united in their metropolitan provenance and experience and there has been little consideration of them in relation to each other and in their role together in re-situating the potential threats of the post-war period into a UK domestic setting from mainland Europe. An examination of the fiction of Deighton and Le Carre suggests a different world where the locus of external danger was in the suburban midst of Surrey or Wood Green. This paper will argue that these novels formed an essential role in reawakening the Home Front and alerting people to the removal of the safety and security once promised by the suburbs. -

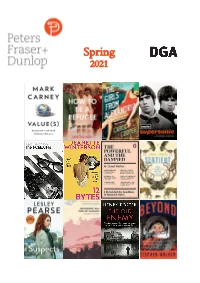

Spring Rights Guide 2021

Spring 2021 CONTENTS PFD FICTION 4 PFD NON-FICTION 24 DGA FICTION 73 DGA NON-FICTION 77 CONTACT 83 PFD FICTION FICTION LILY Rose Tremain ‘One of our most accomplished novelists' Observer “Nobody but she knows that her dream of death is a rehearsal for what will surely happen to her one day. Nobody knows yet that she is a murderer. She is seen as an innocent girl. In one month’s time she will be seventeen.” Foundling, rebel, angel, murderer. At the gates of a park in Bethnal Green in east London, in the year 1850, an abandoned baby is almost eaten by wolves. She is rescued by a young constable, who holds Agent: Caroline Michel the life of this child in his hands, and feels inexplicably drawn to her. Publisher: Chatto & Windus He takes her to The London Foundling Hospital, and Lily Editor: Clara Farmer is placed in foster care at the idyllic Rookery Farm, where she has the happiest of childhood’s, with her beloved Publication: November 2021 foster-mother Nellie. Until one rainy October day Lily is told the chilling news: ‘You’re going to a different place Page extent: 288 now, the place where the other children went, and you must not cry about it’. Rights sold: French (J Clattes) Lily’s a story of bravery, of resilience, of the darkness that German (Suhrkamp) lies within humanity- but also of its warmth. Lily is Italian (Einaudi) staggeringly real, she’s a character who grabs at your heart Russian (Eksmo) from the very first page and refuses to let go. -

Len-Deighton-Mexico-Set.Pdf

LEN DEIGHTON Mexico Set I 'Some of these people want to get killed,' said Dicky Cruyer, as he jabbed the brake pedal to avoid hitting a newsboy. The kid grinned as he slid between the slowly moving cars, flourishing his newspapers with the controlled abandon of a fan dancer. 'Six Face Firing Squad'; the headlines were huge and shiny black. 'Hurricane Threatens Veracruz.' A smudgy photo of street fighting in San Salvador covered the whole front of a tabloid. It was late afternoon. The streets shone with that curiously bright shadowless light that precedes a storm. All six lanes of traffic crawling along the Insurgentes halted, and more newsboys danced into the road, together with a woman selling flowers and a kid with lottery tickets trailing from a roll like toilet paper. Picking his way between the cars came a handsome man in old jeans and checked shirt. He was accompanied by a small child. The man had a Coca Cola bottle in his fist. He swigged at it and then tilted his head back again, looking up into the heavens. He stood erect and immobile, like a bronze statue, before igniting his breath so that a great ball of fire burst from his mouth. 'Bloody hell!' said Dicky. 'That's dangerous.' 'It's a living,' I said. I'd seen the fire-eaters before. There was always one of them performing somewhere in the big traffic jams. I switched on the car radio but electricity in the air blotted out the music with the sounds of static. It was very hot. -

Martin Bormann

MARTIN BORMANN NAZI IN EXILE By Paul Manning To my wife, Peg, and to our four sons, Peter, Paul, Gerald and John, whose collective encouragement and belief in this book as a work of historic impor- tance gave me the necessary persistence [FACSIMILE ELECTRONIC EDITION 2005] and determination to keep going. First edition Copyright © 1981 by Paul Manning All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Queries regarding rights and permissions should be addressed to: Lyle Stuart Inc., 120 Enterprise Ave., Secaucus, N. J. 07094 Published by Lyle Stuart Inc. Published simultaneously in Canada by Musson Book Company, a division of General Publishing Co. Limited, Don Mills, Ont. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Manning, Paul. Martin Bormann, Nazi in exile. Includes index. 1. Bormann, Martin, 1900-1943[?]. 2. National socialism—Biography. 3. War criminals—Germany— Biography. I. Title. DD247.B65M36 943.086'092'4 [B] 81-5696 ISBN 0-8184-0309-8 AACR2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Allen W. Dulles, for his encouragement and assurance that I was “on the right track, and should keep going,” after reading my German research notes in preparation for this book, during the afternoons we talked in his house on Q Street in Washington, D.C. To Robert W. Wolfe, director of the Modern Military Branch of the National Archives in Washington, his associate John E. Taylor, and George Chalou, supervisor of archivists in the Suitland, Maryland, branch of the National Archives, whose collective assistance in my search for telling documents from both sides of World War II contributed substantially to the his- torical merits of this book. -

Books for You: a Booklist for Senior High Students

'DOCUMENT RESUME ED 130 270 CS 202 973 AUTHOR Donelson, Kenneth L., Ed.; And Others TITLE Books for You: A Booklist for Senior High Students. Sixth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE 76 NOTE 490p.; Compiled by the Committee on the Senior High School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English AVAILABLE gRomNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Stock No. 03626, $2.95 non-member, $2.25 member) .EDRS PRICE MF-$1.00 HC-$26.11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Annotated Bibliographies; *Booklists; *Books; *High School Students; literature; Reading, Materials; Secondary Education; Teenagers ABSTRACT The books listed in this annotated bibliography have been selected to provide pleasurable reading for,high school students. Books are arranged alphabetically by author,under 43_main categories. Concluding the book are a directory of publishersand indexes of authors and titles. (JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makesevery effort * * to obtain'the best'copy available. Nevertheless, itemsof marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality. * * .of the:microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS isnot * responsible for the quality.of the original document. leproductions* * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. * *********************************************************************** . U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE DF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN- ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE- SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF z EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Middlebury Book List.Xlsx

Reading Recommendations from Middlebury Classmates 1971 Last Name Recommended by Title Author Last Author First Genre/Category Comments We Pointed Them North: Recollections of a E.C. "Teddy Blue" and Johnson Clara Johnson Pincus Cowpuncher Abbott and Smith Helena Huntington Biography/Autobiography Nonnie T. and Helena Johnson Clara Johnson Pincus A Bride Goes West Alderson and Smith Huntington Biography/Autobiography Yerpe Anne Kavcic Chaboyer Karen Biography/Autobiography Hall Myrka Hall-Beyer Grant Chernow Ron Biography/Autobiography Mister Doctor: Janusz Korcak & the Orphans Johnson Clara Johnson Pincus of the Warsaw Ghetto Cohen-Janca Irène Biography/Autobiography illustrated by Maurizio Quarello any of the works of psychologist Robert Coles, from his conversations with children (especially Children of Crisis, Vol. 1: A Study of Courage and Fear; The Moral Life of Johnson Clara Johnson Pincus Children; The Spiritual Life of Children) Coles Robert Biography/Autobiography Johnson Clara Johnson Pincus This House of Sky Doig Ivan Biography/Autobiography Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An Johnson Clara Johnson Pincus African Childhood Fuller Alexandra Biography/Autobiography Tine Donald Tine Caesar: Life of a Colossus Goldsworthy Adrian Biography/Autobiography Hailed "a masterwork" by the WSJ, this book covers the years between Elvis's army service in Germany in 1958 to his tragic Lindsay Karen Lindsay Palmer Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley Guralnick Peter Biography/Autobiography death at age 42 in 1977. Listen to Elvis's "Milkcow Blues Boogie" (1955), and you might see why Elvis began to Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis fascinate me. He was so much more than the Lindsay Karen Lindsay Palmer Presley Guralnick Peter Biography/Autobiography has-been we knew in the 1970s.