The Function of Anarchist Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Download As a PDF File

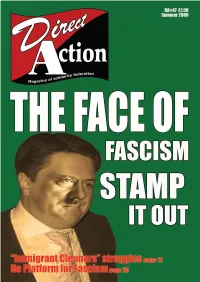

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

New Anarchist Review Advertising in the Newanarchist Review June 1985, While on Their C/O 84B Whitechapel High Street Costs from £10 a Quarter Page

i 3 Balmoral Place Stirling, Scotland For trade distribution contact FK8 2RD 84b Whitechapel High Street London E1 7QX M A I L OR D E R Tel/fax 081 558 7732 DISTRIBUTION R iii-'\%1[_ X6%LE; 1/ ‘3 _|_i'| NI Iii O ‘Puxlci-IUi~lF G %*%ad,J\..1= BLACK _..ni|.miu¢ _ RED I BLQCK ... Rnmcho-lymhcufld *€' BREEN a BLMIK.....iiiuachv-Queen ,1-\ Plianchmle 5;7P%""¢5 L0 ..,....0u ab»! ’____ : <*REE"--I-=~‘~siw mi. Punchline *8: Let us Pray "'""~" 9"" Punchline *9: Time to remove GREEN 5 PURPLE.....Uc.ncn4 Jufflu N TFllAI\IGl_ESRq, ____, ,,,,,,,,,, Punchline ,10: Censorship oi bi"EEl'L ,,,l -znwiuli 8 $g?L":]":' """*'”"‘ L?;LB5"£5"";" Each copy £1 (post pai'd) in UK. M, ,,'f,‘;,'1;¢.5 are 11 30 Mm European orders £1.20 (post paid) mmoguijifgmflgrmfj, Mme European wholesale welcome Make cheques payable to ‘J Elliott’ only. Big Bang, Plain Wrapper comix, Punchline, Fixed Grin, Anti Shirts Catalogue from: BM ACTIVE LONDON WC1 N 3XX, LONDO 1M1Nflilllillilfilll __-rwuew ANARCH‘: ' ' '1... l'|1W ANARCHIST REVIEW NEW TITLES These titles are available from A Distribution (trade) counts what happened to No. 21 S September 1992 and AK Press (mail order) unless otherwise stated. several hundred travellers, See back page for addresses. who were attacked in a mili- Published by: Advertise taiy-style police operation in New Anarchist Review Advertising in the NewAnarchist Review June 1985, while on their c/o 84b Whitechapel High Street costs from £10 a quarter page. Series ANARCHY BY AN druggists’, or hard by a win- way to the Stonehenge festi- London E1 7QX discounts available. -

Revolution by the Book

AK PRESS PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2009 AKFRIENDS PRESS OF SUMM AK PRESSER 2009 Friends of AK/Bookmobile .........1 Periodicals .................................51 Welcome to the About AK Press ...........................2 Poetry/Theater...........................39 Summer Catalog! Acerca de AK Press ...................4 Politics/Current Events ............40 Prisons/Policing ........................43 For our complete and up-to-date AK Press Publishing Race ............................................44 listing of thousands more books, New Titles .....................................6 Situationism/Surrealism ..........45 CDs, pamphlets, DVDs, t-shirts, Forthcoming ...............................12 Spanish .......................................46 and other items, please visit us Recent & Recommended .........14 Theory .........................................47 online: Selected Backlist ......................16 Vegan/Vegetarian .....................48 http://www.akpress.org AK Press Gear ...........................52 Zines ............................................50 AK Press AK Press Distribution Wearables AK Gear.......................................52 674-A 23rd St. New & Recommended Distro Gear .................................52 Oakland, CA 94612 Anarchism ..................................18 (510)208-1700 | [email protected] Biography/Autobiography .......20 Exclusive Publishers CDs ..............................................21 Arbeiter Ring Publishing ..........54 ON THE COVER : Children/Young Adult ................22 -

A Journal of Mutualist Anarchist Theory and History

LeftLiberty “It is the clash of ideas that casts the light!” The Gift Economy OF PROPERTY. __________ A Journal of Mutualist Anarchist Theory and History. NUMBER 2 August 2009 LeftLiberty It is the clash of ideas that casts the light! __________ “The Gift Economy of Property.” Issue Two.—August, 2009. __________ Contents: Alligations—A Tale of Three Approximations 2 New Proudhon Library Announcing Justice in the Revolution and in the Church—Part I 6 The Theory of Property, Chapter IX—Conclusion 8 Collective Reason “A Little Theory,” by Errico Malatesta 23 “The Mini-Manual of the Individualist Anarchist,” by Emile Armand 29 From the Libertarian Labyrinth 34 Socialism in the Plant World 35 “Mormon Co-operation,” by Dyer D. Lum 38 “Thomas Paine’s Anarchism,” by William Van Der Weyde 41 Mutualism: The Anarchism of Approximations Mutualism is APPROXIMATE 45 Mutualist Musings on Property 50 The Distributive Passions Another World is Possible, “At the Apex,” I 72 On alliance “Everyone here disagrees” 85 Editor: Shawn P. Wilbur A CORVUS EDITION LeftLiberty: the Gift Economy of Property: If several persons want to see the whole of a landscape, there is only one way, and that is, to turn their back to one another. If soldiers are sent out as scouts, and all turn the same way, observing only one point of the horizon, they will most likely return without having discovered anything. Truth is like light. It does not come to us from one point; it is reflected by all objects at the same time; it strikes us from every direction, and in a thousand ways. -

The Curious George Brigade

THE INEFFICIENT UTOPIA (or “How Consensus Will Change The World”) The Curious George Brigade Over and over again, anarchists have been collectives, and do-it-yourself ethics. A place critiqued, arrested, and killed by “fellow- where time is not bought, sold, or leased, and travelers” on the road to revolution because we no clock is the final arbiter of our worth. For were deemed inefficient. Trotsky complained to many people in North America, the problem is his pal Lenin that the anarchists in charge of the not just poverty but lack of time to do the things railways were “…inefficient devils. Their lack of that are actually meaningful. This is not a punctuality will derail our revolution.” Lenin symptom of personal failures but the agreed, and in 1919, the anarchist Northern consequence of a time-obsessed society. Rail Headquarters was stormed by the Red Today, desire for efficiency springs from the Guard and the anarchists were “expelled from scarcity model which is the foundation of their duties.” Charges of inefficiency were not capitalism. Time is seen as a limited resource only a matter of losing jobs for anarchists, but when we get caught up in meaningless jobs, an excuse for the authorities to murder them. mass-produced entertainment, and—the Even today, anarchist principles are common complaint of activists—tedious condemned roundly by those on the Left as meetings. So let’s make the most of our time! In simply not efficient enough. We are derided our politics and projects, anarchists have rightly because we would rather be opening a squat or sought to find meaning in the journey, not cooking big meals for the hungry than selling merely in the intended destinations. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

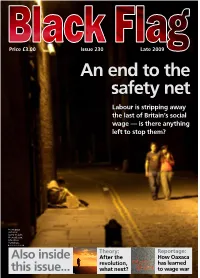

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

Bulletin N°74

Centre International de Recherches sur l’Anarchisme Bulletin du CIRA 74 PRINTEMPS 2018 Illustration de couverture: Dessin de Tilo Steireif, «Réflexion sur l’art, l’éducation et l’avant-garde / Reflexion über Kunst, Bildung und Avan- tgarde», pour l’exposition Anarchie ! Fakten und Fiktionen au Strauhof de Zurich (10 juin au 4 septembre 2016). Extrait de Buchcollage, 20 x 30 cm, 75 p. Le dessin fait référence à L’Avant-Garde cosmopolite (Paris, 1887, 8 numéros) et à L’Avenir, organe ouvrier indépen- dant de la Suisse romande (Genève, 1893-1894, 17 numéros, conservé au CIRA sous la cote Pf 206, incomplet). Bulletin du CIRA Lausanne N°74, printemps 2018 Sommaire Rapport d'activités 2017 p. 2 La coopération est bonne pour la recherche p. 6 Un elogio alle fonti orali della storia delle militanti anarchiche p. 9 Des nouvelles des archives p. 14 Hommage à Mai 1968 p. 16 Ressources en ligne : MayDay Rooms p. 21 Quelques notes sur l’anarchisme en Roumanie p. 23 La pierre tombale de Bertoni p. 32 Mise à disposition du fichier biobibliographique p. 33 Hommage à Eduardo Colombo p. 36 Liste des nouvelles acquisitions p. 38 Xylogravure, David Orange pour le CIRA 1 Rapport d’activités 2017 Préambule Depuis ses débuts dans une là pour gagner quelques centi chambre louée à Genève, le CIRA a mètres, ou de se rendre compte de vu ses collections s'étoffer, c'est le problèmes de classification. On a moins que l'on puisse dire ! Si en aussi pris le temps de faire des 1957 la base était constituée par les plans de l'état des collections (envi archives du journal Le Réveil, des ron 200 mètres linéaires (ml) pour journaux et publications reçus en les livres et autant pour le reste des échange ainsi que par la Biblio collections) ainsi qu'une estimation thèque Germinal de l’ancien groupe de l'accroissement des collections anarchiste local, les 130 mètres car par langues sur 10 ans (au total rés de locaux construits en 1989 40 ml en plus pour les livres et spécialement pour accueillir les col 30 ml pour les autres collections). -

London Anarchist Bookfair 2011

' Q. - - 15¢ - . -* _, I,_I -I| \ __IL .>:-A-.-~-*.-br---='-‘-:;f.;.-7-:§;' -: 17,7‘~-..-w-:'i:‘~»:-i- M‘-1. -, -r, \ DO ARCHIST 1- - . .\ .- - -,.\. ~ O __ f._\I,".I . .- I. \ . \ I \\,-I,'$\;;. '- Iv.' I‘ 1&2,'-'-. -''._*. :-.~.~,. |\ ',.-,--_== .-| . _ {Q I_\'_ " 1 ', - . -. -.. ~ I.,,I,_,p-.- .~|. \!:-\\\!-.--| -t"“‘-‘"1-. -'."‘- . I‘-1. - ~. |- '§ V; . - -=- .\-, - -I, .|I.I__. - -_I.“-I I I: I _ u. '%= . II ,- I I.II_,._ ._ ;_\ . III II, ..:I -I-MI-_-;_. ' \\l"" .1‘ ‘.1 -\ I; |"', P" /. -'1=-._ .- _.;~.\1- . I-- | r 1?’*;!=_1-.- - -W’. _ 1' 7 .,-, M Saturday 22nd October 10am to 7pm .- . *1‘ 1"‘ I |,‘ _____ U. Z“ .__.._____ ‘ ,. ,H\"\\'-. 0‘\\\I~ \.. 1% I \,I\‘,|\‘.~\\‘.§.‘3‘_.,4‘ _;Ij-" »:;.-;-. - " ' _\-.*;=__ O ,/ rt » “*5 4’- |..; W | a kqi" \ X‘ t, ‘Q ,,;...-I-—> 5. T. 1‘ \ 2% \III ,1‘.-' II? ma- ‘ \\ ,I‘I hfw ,, aa- n \‘5 \ v <,___._ n ,.I _.,.I. III ‘I ;.:;<:@1-1z%‘"-P-'=‘-A>-Ii.‘H '*~\ -.\ - ‘ ~\ ox, ~ .. -- "*?§W‘-\- ~b_‘_.,.~:\»»:-~*;..\\3 ' _. ~-w- V - ‘ W W, \ '.\'. II. I,I.' --.'."-' I I .I ‘I. \ .§\' “ II‘;\\ Mm' I II\I\II\\\ I II I I I . 'M - I ' E I‘ -:‘::'f|‘.:§'< \' - - 1-I -‘ ‘ “guy " \ 'I\ - \ - "._\‘*. ‘ \Qe.\‘§-,~3**.\j-.',;~.-.gv.- '1‘- -‘Kl '.:11:-!:TI‘éi’:'t:t-:~J-i-:-;j-: \* ‘A -‘ 1 W‘ “~ I-~\'i§.\\\\"-.~_ . -' ~\\ ‘ ll‘ , "'vq\'\., \\' " Q .< --..\ “,II ' -. - = _ \';-"l:3I;'_.-.'-=: ' \ -M 1'1 ..n~.\(\~I\IIIMIII.II_IIIIIII' .\" ‘ ‘ ' , . I . __, .. - r ' ' '1 . ..,.....-, ~~'-- I; \ \I, -- - 1 I ' 1:_._ - - -..-' -- 1 I - .- -'.' ’ \ , F\- --,, ,r -\‘ 1 , \ II ‘ I E~ \ AG ‘ |. “ ..\ ‘V, \ | gr“,\ . I- . \"-1‘,1‘ _II\| I .-tc - -' '._-t\ -"1-. -

Do Anarchists Believe in Freedom?

Wayne Price Do Anarchists Believe in Freedom? The Anarchist Library Contents Freedom under capitalism...................... 3 What about the “rights” of Fascists?............... 5 The socialist-anarchist revolution must be freely self-organized6 Freedom for all includes the right of national self-determination6 References............................... 8 2 Central to anarchism is the belief that people can organize themselves to efficiently meet their needs, without top-down hierarchies, coercion, or rewards and punishments. People will make mistakes, because we are imperfect, but we can learn from our mistakes and improve over time. This is the belief in freedom. Anarchism is usually presented as the most extreme form of a belief in freedom. It has often been said that anarchism is a synthesis of classical liberalism — carried to its extreme — and socialism. Another historical name for anarchism (and antistatist Marxism) is “libertarian socialism.” Yet there is a certain amount of ambiguity among anarchists about freedom. There are topics on which some — many — anarchists reject the pro-freedom, libertarian, position. For example, concerning freedom of speech. Some anarchists have general- ized from our attitude toward fascists (where we attempt to physically drive them off the streets and break up their meetings). These anarchists (and other leftists) have applied this to other groups which are non-fascist — conservatives for example — breaking up their meetings (such as assaulting the platform at Columbia University in New York City of the group which organized “Islamo- fascist Week”). Or anarchists are often against admitting Marxist-Leninists to anarchist gatherings or bookfairs — not only denying them literature tables (which may make sense at an anarchist bookfair) but questioning their right to attend. -

MKE Lit Su Pp Ly

[March, 2021] MKE Lit Supply -PO Box 11883, Milwaukee WI 53211 Milwaukee Literature Supply Order Form Name:_______________________________DOC#______________ Facility: _______________________________ Mailing Address: _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Catalog # Title Author Ex: BA001 From Somewhere in the World: Assata Shakur Anonymous Speaks A Message to the New Afrikan Nation If you would like us to send something not in this catalog, please tell us as much as you can about the particular writing (in the spaces below) and we will do our best to get it to you! please return to: Milwaukee Literature Supply, PO Box 11883, Milwaukee WI 53211 [March, 2021] MKE Lit Supply -PO Box 11883, Milwaukee WI 53211 Page - 11 - Hey, we are anarchists from Milwaukee! We care about and want to provide something meaningful and reliable to anyone This project is for sending radical reading materials free of charge to anyone who requests them. amps or anything like that what we are doing will cost you nothing at all! Just let us know Our address is: Milwaukee Literature Supply PO Box 11883 Milwaukee, Wi 53211 Please limit your order to five items at a time, and anticipate 1-3 week(s) for delivery. You can always order more in the future. You can write out the item. Feel free to share this catalog with friends so they can order something as well. If you need a new copy of this catalog, we can also send it at any time. adding them if possible. Thanks and enjoy! MKE Lit Supply te m Your friends and family on the -

An Anarchist Journal of Dangerous Living

Rolling Thunder issue number one / summer two-thousand five / a broadcast from the CrimethInc. Workers’ Collective an anarchist journal of dangerous living A fault line runs through every society, through every community, through every human heart. On one side is obedience; on the other, freedom. On one side is cowardice; on the other, compassion. On one side is despair; on the other, action. Sometimes the boundaries shift as gains are made or lost— but however things appear, that fault line is always there. Most everything you can read nowadays is published from one side of this divide. This magazine hails from the other. “Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit upon his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats.” –Henry Louis Mencken “ see you, and I know that my dreams are right, right a thousand times over, just Ias your dreams are. It is life The first step must be the secession of intelligent pioneers from this society. table of and reality that are wrong. I understand it only too well, your dislike of politics, your ONE ANARCHIST, ONE REVOLUTION despondence over the chatter Contents and antics of the parties and the press, your despair over the war, the one that has been and Opening Salvo the one that is to be, over all 2 Living Dangerously that people think, read, and 3 Invitation to Participate build today, over the music 4 Reader Survey they play, the celebrations they 5 Glossary of Terms hold, the education they carry Letters on. Whoever wants to live and 8 Live from Jail Following Georgia’s G8 Protests..