Volume 37 2010 Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel Restrictions 21 June 2010

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel restrictions 21 June 2010 1. Deleted. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide a general update on the situation for Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) members, both rank and file members and prominent leaders, in respect to their possible treatment and risk of serious harm in Zimbabwe. The situation for MDC members is precarious, as is borne out by the following reports which indicate that violence is perpetrated against them with impunity by Zimbabwean police and other Law and Order personnel such as the army and pro-Mugabe youth militias. Those who are deemed to be associated with the MDC party either by family ties or by employment are also adversely treated. The latest Country of Origin Information Report from the UK Home Office in December 2009 provides recent chronology of incidents from July 2009 to December 2009 where MDC members and those believed to be associated with them were adversely treated. It notes that there has been a decrease in violent incidents in some parts of the country; however, there was also a suspension of the production of the „Monthly Political Violence Reports‟ by the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum (ZHRF), so that there has not been a comprehensive accounting of incidents: POLITICALLY MOTIVATED VIOLENCE Some areas of Zimbabwe are hit harder by violence 5.06 Reporting on 30 June 2009, the Solidarity Peace Trust noted that: An uneasy calm prevails in some parts of the country, while in others tensions remain high in the wake of the horrific violence of 2008…. -

19 October 2009 Edition

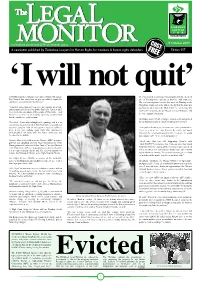

19 October 2009 Edition 017 HARARE-Embattled‘I Deputy Agriculturewill Minister-Designate not quit’He was ordered to surrender his passport and title deeds of Roy Bennett has vowed not to give up politics despite his one of his properties and not to interfere with witnesses. continued ‘persecution and harassment.’ His trial was supposed to start last week on Tuesday at the Magistrate Court, only to be told on the day that the State was “I am here for as long as I can serve my country, my people applying to indict him to the High Court. The application was and my party to the best of my ability. Basically, I am here until granted the following day by Magistrate Lucy Mungwira and we achieve the aspirations of the people of Zimbabwe,” said he was committed to prison. Bennett in an interview on Saturday, quashing any likelihood that he would leave politics soon. On Friday, Justice Charles Hungwe reinstated his bail granted He added: “I have often thought of it (quitting) and it is an by the Supreme Court in March, resulting in his release. easiest thing to do, by the way. But if you have a constituency you have stood in front of and together you have suffered, “It is good to be out again, it is not a nice place (prison) to be. there is no easy walking away from that constituency. There are a lot of lice,” said Bennett. He said he had hoped So basically I am there until we return democracy and that with the transitional government in existence he would freedoms to Zimbabwe.” not continue to be ‘persecuted and harassed”. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

University of St. Thomas Presents Morgan Tsvangirai and Roy Bennett Walk with Me: ‘The Struggle for Freedom and Hope in Zimbabwe’

News Release Contact: Sandra Soliz 713-906-7912 [email protected] University of St. Thomas presents Morgan Tsvangirai and Roy Bennett Walk with Me: ‘The Struggle for Freedom and Hope in Zimbabwe’ WHAT: University of St. Thomas presents two of the most effective opposition leaders in Zimbabwe today, Morgan Tsvangirai and Roy Bennett, discussing the current political and social situation in Zimbabwe. WHEN: 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 9 WHERE: Cullen Hall, 4001 Mt. Vernon University of St. Thomas Parking available in the Moran Center, Graustark and West Alabama BACKGROUND: • Zimbabwe, 10 years ago the breadbasket of Africa, now faces mass starvation. Land seizures, slum “clearance” and price controls have left fields brown, stores empty and cities dark. People have no jobs, no transport, and no food. • Life expectancy for men has fallen from 60 to 37, lowest in the world. For women, it is lower, 34. Twelve million people once lived in Zimbabwe; more than three million have fled. • The Movement for Democratic Change, led by former union leader Morgan Tsvangirai, opposing these policies, won 58 of the 120 elected seats in Parliament in the last largely free elections of 2000. The Government of President Robert Mugabe closed newspapers, banned political meetings, arrested its opponents. • Today Zimbabwe’s African neighbors, as well as the nations of Europe and America are calling for free and fair elections, but Mugabe stubbornly clings to power. more University of St. Thomas… A Shining Star in the Heart of Houston since 1947 3800 Montrose Blvd. Houston, TX 77006 713.522.7911 www.stthom.edu University of St. -

AG Fears Upheaval Over SADC Tribunal

30 November 2009 Edition 23 HARARE-The Attorney General, Johannes Charges against Bennett arose in 2006 when The MDC says ZANU PF is frustrating efforts to Hitschmann’s house. The laptop is said to have Tomana last week failed to produce the State’s Hitschmann was allegedly found with an arms swear in Bennett as Deputy Agriculture Minister. contained emails that implicated Bennett in State’sstar witness, Michael Hitschmann to testify cache, which the prosecution saysstar he acquired dims terrorism activities. against Deputy Agriculture Minister-Designate after he was given $5 000 by Bennett to topple Tomana’s prosecution seems to be heading for Roy Bennett forcing the defence lawyers to raise President Robert Mugabe. collapse with the State witnesses having so far accusations of deliberate attempts to fumble failed to directly link Bennett to the charges. The State alleges Hitschmann was paid by Bennett the matter. Bennett’s co-accused, Hitschmann was acquitted One of the witnesses admitted that the police to buy weapons to assassinate government of the same charges of terrorism. had not recorded an inventory of arms alleged to officials. Police say Hitschmann implicated On Friday Tomana, informed High Court Judge, Justice Chinembiri Bhunu that the State’s sixth Bennett denies the charges, which his Movement have been recovered from Hitschmann’s house Bennett in the procurement of the arms, but witness was arms dealer Hitschmann – who is for Democratic Change (MDC) party – led by in 2006. Another witness failed to explain why Bennett’s lawyers argue that the arms dealer said to have implicated Bennett in plotting to Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai - says are weapons alleged to have been recovered had increased from nine to 49. -

OTHER ISSUES ANNEX E: MDC CANDIDATES & Mps, JUNE 2000

Zimbabwe, Country Information Page 1 of 95 ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VIA HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE PAST & PRESENT ANNEX D: FULL ELECTION RESULTS JUNE 2000 (hard copy only) ANNEX E: MDC CANDIDATES & MPs, JUNE 2000 & MDC LEADERSHIP & SHADOW CABINET ANNEX F: MDC POLICIES, PARTY SYMBOLS AND SLOGANS ANNEX G: CABINET LIST, AUGUST 2002 ANNEX H: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 This country report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The country report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The country report is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the country report on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. -

Document De Reference

14APR201007404224 Societ´ e´ anonyme a` conseil de surveillance et directoire Au capital social de 10 254 060 euros Siege` social : 18, rue Troyon 92 316 Sevres` 552 056 152 R.C.S. Nanterre DOCUMENT DE REFERENCE VALANT RAPPORT FINANCIER ANNUEL 18MAY200511402118 En application de son Reglement` gen´ eral´ et notamment de l’article 212-13, l’Autorite´ des marches´ financiers a enregistre´ le present´ document de ref´ erence´ le 13 avril 2010 sous le numero´ R.10-020. Ce document ne peut etreˆ utilise´ a` l’appui d’une operation´ financiere` que s’il est complet´ e´ par une note d’operation´ visee´ par l’Autorite´ des marches´ financiers. Il a et´ e´ etabli´ par l’emetteur´ et engage la responsabilite´ de ses signataires. L’enregistrement, conformement´ aux dispositions de l’article L.621-8-1-I du code monetaire´ et financier, a et´ e´ effectue´ apres` que l’AMF a verifi´ e´ « si le document est complet et comprehensible,´ et si les informations qu’il contient sont coherentes´ ». Il n’implique pas l’authentification par l’AMF des el´ ements´ comptables et financiers present´ es.´ Des exemplaires du present´ document de ref´ erence´ sont disponibles sans frais au siege` social de CFAO, 18, rue Troyon, 92316 Sevres` – France. Le document de ref´ erence´ peut egalement´ etreˆ consulte´ sur les sites internet de CFAO (www.cfaogroup.com) et de l’Autorite´ des marches´ financiers (www.amf-france.org). REMARQUES GENERALES Le present´ document de ref´ erence´ est egalement´ constitutif : • du rapport financier annuel devant etreˆ etabli´ et publie´ par toute societ´ e´ cotee´ dans les quatre mois de la clotureˆ de chaque exercice, conformement´ a` l’article L.451-1-2 du Code monetaire´ et financier et a` l’article 222-3 du Reglement` gen´ eral´ de l’AMF, et • du rapport de gestion annuel du Directoire de la Societ´ e´ devant etreˆ present´ e´ a` l’assemblee´ gen´ erale´ des actionnaires approuvant les comptes de chaque exercice clos, conformement´ aux articles L.225-100 et suivants du Code de commerce. -

When Is the Right Time for a Ceasefire in Afghanistan?

WHEN IS THE RIGHT TIME FOR A CEASEFIRE IN AFGHANISTAN? Center for Strategic & Regional Studies - Kabul CSRS ANALYSIS | Issue No. 363 17 January 2021 Website: www.csrskabul.com - www.csrskabul.af We welcome your feedback and suggestions for the improvement of CSRS ANALYSIS at: Email: [email protected] - [email protected] WHEN IS THE RIGHT TIME FOR A CEASEFIRE IN AFGHANISTAN? Looking at the sedate and complicated Intra-Afghan peace negotiations1, it seems that the arrival at a mutually acceptable arrangement for the war in Afghanistan is likely to take a long time. It will require negotiators from both the Afghan government and the Taliban to tackle the delicate political issues and the future of a government underlying the conflict. In the few months that the representatives sat at the negotiation table, we have seen that the killings, atrocities and destruction continued, perhaps more than before the official start of the peace process. As the Intra-Afghan peace negotiations enter into a critical phase, many would ask, when is the right time for a ceasefire? Of course, ordinary Afghans more than anyone else yearn for the soonest possible cessation of the conflict that takes its toll every single day from the innocent citizens. Indeed, moral and human principles teach us that every life is important and should be preserved and saved whenever possible. But what does history teach us? When is the right time for a ceasefire and to interrupt a war (in this case the war in Afghanistan)? Should it be before or after the Intra-Afghan negotiations -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CORRELATES OF ADULT OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY IN UPSTATE NEW YORK By STACEY ANN GIROUX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Stacey Ann Giroux 2 To Mom and Pop 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people supported me not only while I worked on this research but also throughout my time in graduate school. My parents, Don and Chris Giroux, never told me I couldn’t be or do anything, whether as a young child with aspirations as a leaf- picker or as an idealistic twenty-something who believed she could make a difference in the world as an anthropologist. They also provided help, shelter and money at various difficult points during graduate school. For this and more I thank them. My sister, Carolyn Giroux, has provided comic relief and her excellent proofreading skills. James Wells, who was a close friend when I began graduate school and is now my partner of eight-plus years, I thank especially for emotional support. His is a unique soul, and, having gone through the dissertation process himself, he always seemed to know what to say, what not to say, when to push me, and perhaps most importantly, when to simply listen. When I was still an undergraduate at the University of Missouri, Gery Ryan’s medical anthropology class inspired me to switch from archaeology to cultural anthropology almost overnight. Gery is the person I would call my first mentor, and he showed me that it was possible to pursue anthropology as a career, that I had the right stuff for it, and then helped me to do just that. -

Zimbabwe's Operation Murambatsvina

ZIMBABWE'S OPERATION MURAMBATSVINA: THE TIPPING POINT? Africa Report N°97 -- 17 August 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION: OPERATION MURAMBATSVINA.......................................... 1 A. WHAT HAPPENED .................................................................................................................1 B. WHY IT HAPPENED ...............................................................................................................3 1. The official rationale..................................................................................................3 2. Other explanations .....................................................................................................4 C. WHO WAS RESPONSIBLE?.....................................................................................................5 II. INTERNAL RESPONSE ............................................................................................... 7 A. THE GOVERNMENT: OPERATION GARIKAI ............................................................................7 B. ZANU-PF ............................................................................................................................8 C. THE MDC.............................................................................................................................9 D. A THIRD WAY?...................................................................................................................11 -

ECFG-Niger-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment (Photos courtesy of IRIN News 2012 © Jaspreet Kindra). Niger Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Niger, focusing on unique cultural features of Nigerien society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Standard Note: SN06695 Last Updated: 5 August 2013

In brief: Zimbabwe – 2013 elections Standard Note: SN06695 Last updated: 5 August 2013 Author: Jon Lunn Section International Affairs and Defence Section Zimbabwe held presidential and parliamentary elections on 31 July 2013. They resulted in overwhelming victory for President Robert Mugabe and his Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and shattering defeat for Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai and his Movement for Democratic Change-Tsvangirai (MDC-T). The elections bring to an end over four years of ‘power-sharing’ under the February 2009 Global Political Agreement (GPA) that followed the violence-ridden elections of 2008, which were stolen by ZANU-PF. The 2013 elections were certainly extremely flawed – it had been obvious for some time that they would be – but there is no escaping the fact that President Mugabe and ZANU-PF have comprehensively outmanoeuvred their rivals since the GPA was agreed, in the process rebuilding a domestic political constituency on promises of ‘indigenising the economy’, combined with an often ruthless reassertion of a self-proclaimed ‘right to rule’. As one analyst, James Muzondidya, put it in an excellent book published earlier this year: The ZANU-PF strategy, consistent with its hegemonic political culture, has been to engage in cosmetic political and economic reforms that will not result in further democracy or result in a loss of its historic monopoly on power [...] Indeed, over the last four years, ZANU-PF has kept the strategic doors to its power, such as the security sector and the mining and agricultural industries, firmly closed. While acknowledging the major constraints that the opposition faced under the GPA, Muzondidya is highly critical of its performance, viewing its top leadership as often having been naive and noting that a significant number of MDC-T councillors at the municipal level became embroiled in corruption scandals, damaging the party’s claim to represent change.