Halifax, Nova Scotia April2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southeast Asian Traditions in the Philippines1 Lawrence A

Southeast Asian Traditions in the Philippines1 Lawrence A. Reid University of Hawai`i Introduction The Philippines today is home to over one hundred different ethnolinguistic groups. These range from the Arta, a tiny group of Negrito hunter-gatherers with only about a dozen remaining speakers, living under highly adverse conditions in Quirino Province, to the 12,000,000 or so Tagalogs, a very diverse group primarily professing Catholicism, centered around Metro-Manila and surrounding provinces, but also widely dispersed throughout the archipelago. In between there are a wide range of traditional societies living in isolated areas, such as in the steep mountains of the Cordillera Central and the Sierra Madre of Northern Luzon, still attempting to follow their pre-Hispanic cultural practices amid the onslaught of modern civilization. And in the Southern Philippines there are the societies, who, having converted to Islam only shortly before Magellan arrived, today feel a closer allegiance to Mecca than they do to Manila. These peoples, despite the disparate nature of their cultures, all have one thing in common. They share a common linguistic tradition. All of their languages belong to the Austronesian language family, whose sister languages are spread from Madagascar off the east coast of Africa, through the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago, scattered through the mountains of South Vietnam and Kampuchea as far north as Hainan Island and Taiwan, and out into the Pacific through the hundreds of islands of the Melanesian, Micronesian and Polynesian areas. The question of how all these languages are related to one another, where their parent language may have been spoken, and what the migration routes were that their ancestors followed to bring them to their present locations has occupied scholars for well over a hundred years. -

A Case Study of Statutory Minimum Wage in Hong Kong

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Political Sciences 8-7-2015 Newspaper portrayal and legislative voting process : a case study of statutory minimum wage in Hong Kong Ngai Chiu WONG Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/pol_etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wong, N. C. (2015). Newspaper portrayal and legislative voting process: A case study of statutory minimum wage in Hong Kong (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/pol_etd/14/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Sciences at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. NEWSPAPER PORTRAYAL AND LEGISLATIVE VOTING PROCESS: A CASE STUDY OF STATUTORY MINIMUM WAGE IN HONG KONG WONG NGAI CHIU MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2015 NEWSPAPER PORTRAYAL AND LEGISLATIVE VOTING PROCESS: A CASE STUDY OF STATUTORY MINIMUM WAGE IN HONG KONG by WONG Ngai-chiu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Social Sciences (Political Science) Lingnan University 2015 ABSTRACT Newspaper Portrayal and Legislative Voting Process: A Case Study of Statutory Minimum Wage in Hong Kong by WONG Ngai-chiu Master of Philosophy Statuary Minimum Wage (SMW) has been discussed for 13 years in post-colonial Hong Kong and was finally legislated for in 2010. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 May 2011 10073 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 May 2011 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. 10074 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 May 2011 THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. -

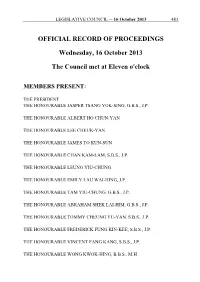

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 16

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 16 October 2013 483 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 16 October 2013 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 484 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 16 October 2013 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, B.B.S. -

Revisiting the Position of Philippine Languages in the Austronesian Family

The Br Andrew Gonzalez FSC (BAG) Distinguished Professorial Chair Lecture, 2017 De La Salle University Revisiting the Position of Philippine Languages in the Austronesian Family Lawrence A. Reid University of Hawai`i National Museum of the Philippines Abstract With recent claims from non-linguists that there is no such thing as an Austronesian language family, and that Philippine languages could have a different origin from one that all comparative linguists claim, it is appropriate to revisit the claims that have been made over the last few hundred years. Each has been popular in its day, and each has been based on evidence that under scrutiny has been shown to have problems, leading to new claims. This presentation will examine the range of views from early Spanish ideas about the relationship of Philippine languages, to modern Bayesian phylogenetic views, outlining the data upon which the claims have been made and pointing out the problems that each has. 1. Introduction Sometime in 1915 (or early 1916) (UP 1916), when Otto Scheerer was an assistant professor of German at the University of the Philippines, he gave a lecture to students in which he outlined three positions that had been held in the Philippines since the early 1600’s about the internal and external relations of Philippine languages. He wrote the following: 1. As early as 1604, the principal Philippine languages were recognized as constituting a linguistic unit. 2. Since an equally early time the belief was sustained that these languages were born of the Malay language as spoken on the Peninsula of Malacca. -

Theories of External-Internal Political Relationships

THEORIES OF EXTERNAL·INTERNAL POLITICAL RELATIONSHIPS: A CASE STUDY OF INDONESIA AND THE PHILIPPINES MARTIN MEADOWS ONE OF THE CHIEF INTERNATIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF the upheaval in Indonesian politics that began late in 1965 has been the termination of former President Sukarno's policy of Konfrontasi aimed at the Federation of Malaysia. Most analyses of the repercussions of that policy have concentrated, understandably, on Indonesia and Ma- laysia and on those major powers with interests in Southeast Asia. There has been relatively little attention, scholarly or otherwise, to the impli- cations of Konfrontasi either for Southeast Asia as a whole, or for indi- vidual countries in that region. A study of the latter kind, aside from helping to fill that gap, could also be designed to contribute to the in- vestigation of a more general problem - that of developing and test- ing conceptual schemes for the systematic exploration of the relation- ships between the external and internal political behavior of states. These are the major objectives of this paper, which examines the impact of Konfrontasi on a third party, the Republic of the Philippines.1 The primary purpose of this essay is to ascertain the validity and utility of certain theoretical frameworks formulated to handle the external-in- ternal dichotomy mentioned above. This will be attempted in Sections IV-V. To achieve this end, however, will require first a case study, which is presented in Sections I-III. Its goals are to describe Philippine political developments during the "era of Konfrontasi," and to assess the nature and extent of that policy's influence on those developments. -

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3: Macro Report June 05, 2006

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 3: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3: Macro Report June 05, 2006 Country: Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, CHINA. Date of Election: 7 September, 2008. Prepared by: Li Pang-kwong, Ph.D. Date of Preparation: August 2010. NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [√] Parliamentary/Legislative [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [ ] Both [√] Other; please specify: _The Legislative Council in Hong Kong is not divided into Upper and Lower Houses._ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 3: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election? The Chief Executive (CE) in Hong Kong (some equivalent of the president elsewhere) is the highest government officials of the HKSAR Government and does not belong to any political party, which is required by the Chief Executive Election Ordinance (Chapter 569, Laws of Hong Kong). -

Developments in Integrated Aquaculture in Southeast Asia, P

Responsible Aquaculture Development in Southeast Asia Edited by Luis Maria B. Garcia SOUTHEAST ASIAN FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT CENTER AQUACULTURE DEPARTMENT Responsible Aquaculture Development in Southeast Asia Proceedings of the Seminar-Workshop on Aquaculture Development in Southeast Asia organized by the SEAFDEC Aquaculture Department 12-14 October 1999 Iloilo City, Philippines Luis Maria B. Garcia Editor SOUTHEAST ASIAN FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT CENTER Aquaculture Department Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines On the Cover: Harvest of pond-reared grouper ISBN 971-8511-47-4 Published and printed by: Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Aquaculture Department Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Copyright 2001 Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Aquaculture Department Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines All Rights Reserved No part of this publication maybe reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission from the publisher For inquiries: SEAFDEC Aquaculture Department 5021 Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Fax +63 33 3351008, 3362891 E-mail [email protected] AQD website http://www.seafdec.org.ph/ FOREWORD Globally, aquaculture development has been recently recognized as the fastest growing food- producing sector, contributing significantly to national economic development, global food supply and food security. This trend has been very apparent in Southeast Asia where fish is a staple in the people’s diet. Increasing aquaculture production in the region appears to bridge the shortfall relative to the demand for fishery products that capture fisheries can, at present, no longer fulfill. However, this scenario of increased production did not materialize without a consequent trade-off impacting on environmental integrity, socioeconomic development and viability, and technological efficiency that ensure the sustainability of fish production. -

Contemporary Hong Kong Government and Politics Expanded Second Edition

Contemporary Hong Kong Government and Politics Expanded Second Edition Edited by Lam Wai-man Percy Luen-tim Lui Wilson Wong Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2007, 2012 First published 2007 Expanded second edition 2012 ISBN 978-988-8139-47-7 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Contributors vii Acronyms and Abbreviations xi Chapter 1 Political Context 1 Lam Wai-man Part I: Political Institutions 23 Chapter 2 The Executive 27 Li Pang-kwong Chapter 3 The Legislature 45 Percy Luen-tim Lui Chapter 4 The Judiciary 67 Benny Y.T. Tai Chapter 5 The Civil Service 87 Wilson Wong Chapter 6 District Councils, Advisory Bodies, and Statutory 111 Bodies Jermain T.M. Lam PART II: Mediating Institutions and Political Actors 133 Chapter 7 Mobilization and Confl icts over Hong Kong’s 137 Democratic Reform Sing Ming and Tang Yuen-sum vi Contents Chapter 8 Political Parties and Elections 159 Ma Ngok Chapter 9 Civil Society 179 Elaine Y.M. Chan Chapter 10 Political Identity, Culture, and Participation 199 Lam Wai-man Chapter 11 Mass Media and Public Opinion 223 Joseph M. -

A Rising China Affects Ethnic Identities in Southeast Asia

ISSUE: 2021 No. 74 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 3 June 2021 A Rising China Affects Ethnic Identities in Southeast Asia Leo Suryadinata* In this picture, festive lights are reflected on a car in Chinatown on the first day of the Lunar New Year in Bangkok on February 12, 2021. Ethnic Chinese in Thailand are considered the most assimilated in Southeast Asia, and it has been argued that Buddhism is a key factor in this process. Photo: Mladen ANTONOV, AFP. * Leo Suryadinata is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, and Professor (Adj.) at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at NTU. He was formerly Director of the Chinese Heritage Centre, NTU. 1 ISSUE: 2021 No. 74 ISSN 2335-6677 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • From Zhou Enlai to Deng Xiaoping, Beijing’s policy towards Chinese overseas was luodi shenggen (to take local roots), which encouraged them to take local citizenship and integrate themselves into local society. • In the 21st century, following the rise of China, this policy changed with a new wave of xinyimin (new migrants). Beijing advocated a policy of luoye guigen (return to original roots), thus blurring the distinction between huaqiao (Chinese nationals overseas) and huaren (foreign nationals of Chinese descent), and urging Chinese overseas regardless of citizenship to be oriented towards China and to serve Beijing’s interest. • China began calling huaqiao and huaren, especially people in business, to help China support the Beijing Olympics and BRI, and to return and develop closer links with China. • Responses from ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand have been muted, as they are localised and are participating in local politics. -

Philippines–Malaysia Border Region

5. Rice & ransoms: the Indonesia– Philippines–Malaysia border region ‘So long as the seas have no fence, it will not stop’, an interviewee prophesised, referring to smuggling in the border region of Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, where all the borders are in the sea. The area is large and includes many small islands, which makes it difficult to patrol. The region also has its share of non-state armed actors. In Mindanao, in the south of the Philippines, organised non-state armed groups fight for more regional autonomy for the Moro people. In Indonesia, more extremist networks, some linked to the Islamic State, conduct attacks that are often directed against civilians. The region also has groups like the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) that are nominally political but, as Gutierrez writes, ‘better understood as a network of dangerous criminal entrepreneurs, similar to an armed mob’ (2016, p.184) than a non-state armed group with political motives. As the border region is large, this chapter uses two case studies (Figure 5.1): in the east, the route connecting Mindanao in the Philippines, Sabah in Malaysia and North Kalimantan in Indonesia; in the west, the route connecting Mindanao in the Philippines and North Sulawesi in Indonesia. I conducted research in Indonesia’s North Kalimantan (Nunukan) and North Sulawesi (Manado, Tahuna, Bitung) and in Mindanao (Davao, Zamboanga, Cotabato) in the Philippines, in April 2018 and in May–June 2018. In the east, between Mindanao and North Sulawesi, local people from the Philippines and Indonesia cross the border on a regular basis, particularly for fishing. -

(修訂本) List of Stakeholder Groups for Stage 1 Public Engagement

(Revised) (修訂本) List of Stakeholder Groups for Stage 1 Public Engagement Exercise 第一階段公眾參與活動的持份者組別 1 List of Stakeholder Groups for Stage 1 Public Engagement Exercise 第一階段公眾參與活動的持份者組別 Category Page For Performing Arts Venues (表演藝術場地) (a) Performing Arts Groups for Concert Hall/Chamber Music Hall 4-6 (使用音樂廳/室樂演奏廳的表演藝術團體) (b) Performing Arts Groups for Xiqu Centre 7-12 (使用戲曲中心的表演藝術團體) (c) Performing Arts Groups for Mega Performance Venue 13 (使用大型表演場地的表演藝術團體) (d) Performing Arts Groups for Theatres 14-16 (使用劇院的表演藝術團體) (e) Performing Arts Venue Managers and Arts Administrators 17 (表演藝術場地管理人及藝術行政人員) (f) Stage Designers and Theatre Technicians 18 (舞台設計師及劇院技術人員) (g) Hirers and Arts Programme Promoters 19 (租戶和藝術節目推廣機構) For Museums and Exhibition Centres (博物館和展覽中心) (h) Arts associations for visual arts, design, popular culture and 20-25 moving image (視覺藝術、設計、流行文化和活動影像方面的藝術協會/藝團) (i) Arts Organisations, Art Centres and Museums Professionals 26 (藝術團體、藝術中心和博物館團體工作者) (j) Arts Critics, Independent Curators and Arts Publications 27 (藝評家、獨立策展人和藝術刊物工作者) (k) Commercial Galleries, Auction Houses and Hirers of Exhibition Centres 28-30 (商業畫廊、拍賣行和展覽中心租戶) Education, Planning, Tourism, Retail and Others (教育、規劃,旅遊及零售及其他) (l) Arts Foundations and Past Arts Performance Sponsors 31-33 (藝術基金和曾經贊助藝術表演的贊助商) (m) Arts Education and Learning Institutions including 34-35 Universities, Teachers, and Youth Groups (藝術教育及學習機構(包括大學),以及教師及青少年團體) (n) Urban Development and Green Groups 36 (城市發展及環保組織) 2 List of Stakeholder Groups for Stage 1 Public Engagement Exercise 第一階段公眾參與活動的持份者組別