Peake Studies 14-2 April 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

Gormenghast Gormenghast

Department of Dramatic Arts Brock University Niagara Region 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1 Canada T 905 688 5550 x5255 brocku.ca October 24, 2016 A Special Invitation to bring your students for innovative and energizing theatre experiences presented by the Department of Dramatic Arts at Brock University! Gormenghast By Mervyn Peake. Stage adaptation by John Constable. Friday, November 18th at 11:30 am Group tickets start at $12 each, discounts available. Twice a year our faculty and students present Mainstage productions in our new 250¬ seat theatre. Directed and designed by faculty and guest artists, performed and produced by students in our Honours BA program, these productions offer you an affordable opportunity to engage your students with original performances that examine provocative thematic ideas. Stimulating course-related content will animate and enrich your teaching curriculum. Our faculty and students bring you the very best of their work in professional-level productions distinguished by their verve and energy. This is a great opportunity to enhance your teaching and to bring excitement to your classroom with a visit to our theatre. Join us at the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts in our new venue located in downtown St. Catharines, 15 Artists’ Common. Gormenghast By Mervyn Peake. Stage adaptation by John Constable. Directed by Mike Griffin, Assisted by Sydney Francolini Designed by David Vivian Lighting Design by Jennifer Jimenez Sound design by Max Holten-Andersen November 11, 12, 18, 19 at 7:30 pm November 13 at 2:00 pm November 18 at 11:30 am Evil is afoot in the Gormenghast castle! Come join us in this labyrinth of dark corridors, where the bizarre and mysterious come to life. -

ERRATA SLIP Mcguinness, Mark (Ed.), Titus Alone

ERRATA SLIP McGuinness, Mark (ed.), Titus Alone: A New Life ISSN 0309 1309 CLAIRE PEÑATE (PEAKE) – INTRODUCTION line 1, for ‘Titus Alone’ read Titus Alone (ditto lines 15, 22) line 2, for Father read father (ditto lines 5, 24, 31, 33) line 6, for Mother read mother line 7, for that read and line 10, for Titus Groan read Titus Groan line 12, for characters read characters’ line 13, for writs read write line 20, for have read had line 21, for ‘Gormengast’ read Gormenghast line 21, for thought read thought. line 32, for Titus Alone read Titus Alone NICK FREEMAN - ‘THE INTER-WAR ROOTS OF TITUS ALONE’ Bibliography line 2, for Aldington, Richard read Fussell, Paul PIERRE-YVES LE CAM – ‘THE SCIENCE FICTION WORLD OF TITUS ALONE’ Two pages are missing from this article, printed below. The bold text appears in the printed book, and the normal face text is missing. ‘The time gap justifies the new standards and techniques, however incredible they may appear to the contemporary world. Peake's originality consists in doubling the temporal distortion which affects not only the reader but also Titus. The reader senses in the science to come the technological achievements in Titus Alone such as the laser weapon; Titus moves from a medieval environment to a futuristic one, and the earl's wonder is obvious when he sees the scores of rockets or the metal and marble architecture of the dome and the arena: (There) was a copper dome the shape of an igloo but ninety feet in height, with a tapering mast, spider-frail and glinting in the sunlight (...). -

00 Peak Gormenghast-Bd3-B.Indb

MERV YN PEAK E DrittesDrittes Buch DER LETZTE LORD GROAN Aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Annette Charpentier Klett-Cotta Die Übersetzung von Annette Charpentier wurde für diese Ausgabe neu durchgesehen von Alexander Pechmann. Hobbit Presse www.klett-cotta.de/hobbitpresse Die Originalausgabe erschien unter dem Titel »Titus Alone« im Verlag Eyre & Spottiswoode, London © 1959 by Mervyn Peake Für die deutsche Ausgabe © 1983 by J. G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger GmbH, gegr. 1659, Stuttgart Alle deutschsprachigen Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany Schutzumschlag: HildenDesign, München, www.hildendesign.de Artwork: © Birgit Gitschier, HildenDesign unter Verwendung mehrerer Motive von Shutterstock Gesetzt aus der Galliard von Elstersatz, Wildfl ecken Gedruckt und gebunden von GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck ISBN 978-3-608-93923-1 Erste Aufl age der neu durchgesehenen Ausgabe, 2011 Inhalt Vorwort von Michael Moorcock 9 Gormenghast Drittes Buch Der letzte Lord Groan 13 Nachwort der englischen Ausgabe 327 ~ 7 ~ Vorwort von Michael Moorcock Der letzte Lord Groan ist für mich in vielerlei Hinsicht das inter- essanteste der drei Bücher, die Mervyn Peake über den jungen Grafen von Gormenghast schrieb, auch wenn seine Handlung nicht so packend ist wie jene der ersten beiden. Obwohl es eini- ge Jahre lang für das schwächste gehalten wurde, weil ein ver- ständnisloser Lektor es verunstaltet hatte, während Peake sich in den ersten Stadien der Parkinson-Krankheit befand, erwies es sich in der restaurierten Fassung als weitaus besser, als die Kritiker ursprünglich geurteilt hatten. Wenn der Autor und Anthologist Langdon Jones, damals Mitherausgeber der Zeitschrift New Worlds, nicht Peakes Ori- ginalmanuskript durchgeblättert und deutliche Abweichungen zwischen der geschriebenen und der gedruckten Version ge- funden hätte, dann wäre die vorliegende weitaus vollstän digere Fassung nie veröffentlicht worden. -

01 to 06 MAY Terry Waite

Mark Billingham Ross Collins Kerry Brown Maura Dooley Matt Haig Darren Henley Emma Healey Patrick Gale Guernsey Literary Erin Kelly Huw Lewis-Jones Adam Kay Kiran Millwood Hargrave Kiran FestivalLibby Purves 2019 Lionel Shriver Philip Norman Philip 01 TO 06 MAY Terry Waite Terry Chrissie Wellington Piers Torday Lucy Siegle Lemn Sissay MBE Jessica Hepworth Benjamin Zephaniah ANA LEAF FOUNDATION MOONPIG APPLEBY OSA RECRUITMENT BROWNS ADVOCATES PRAXISIFM BUTTERFIELD RANDALLS DOREY FINANCIAL MODELLING RAWLINSON & HUNTER GUERNSEY ARTS COMMISSION ROTHSCHILD & CO GUERNSEY POST SPECSAVERS JULIUS BAER THE FORT GROUP Sophy Henn Kindly sponsored by sponsored Kindly THE INTERNATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE THE GUERNSEY SOCIETY Turning the Tide on Plastic: How St James: £10/£5 Lucy Siegle Humanity (And You) Can Make Our Welcome to the Globe Clean Again seventh Guernsey Presenter on BBC’s The One Show and columnist for the Observer and the Guardian, Lucy Siegle offers a unique and beguiling perspective on environmental issues and ethical consumerism. Turning the Tide on Literary Festival Plastic provides a powerful call to arms to end the plastic pandemic along with the tools we need to make decisive change. It is a clear- eyed, authoritative and accessible guide to help us to take decisive and 13:00 to 14:00 effective personal action. Thursday 2 May Message from Sponsored by PraxisIFM Message from Claire Allen, Terry Waite CBE OGH Hotel: £25 Festival Director This is Going to Hurt Business Breakfast As Honorary I am very proud to welcome Professor Kerry you to the seventh Guernsey Chairman of the Literary Festival! With over Adam Kay Thursday 2 May Brown: The World Guernsey Literary 19:30 to 20:30 60 events for all interests According to Xi Festival it is once and ages, the festival is a Kerry Brown is Professor of again my pleasure unique opportunity to be inspired by writers. -

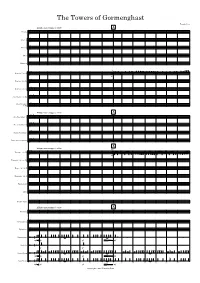

The-Towers-Of-Gormenghast-Web.Pdf

The Towers of Gormenghast Timothy Rees Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Piccolo ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 1 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 2 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Oboe & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bassoon ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Tpt. j j j j j œ œ Clarinet 1 in Bb ° # 6 Œ™ Œ j œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ & # 8 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ œ œ œ œ ∑ mf ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 2 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Clarinet in Eb # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bass Clarinet # in Bb # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Alto Saxophone 1 ° # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Saxophone 2 # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tenor Saxophone # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Baritone Saxophone # # # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 A Allegro non troppo q . = 108 solo Trumpet 1 in Bb ° # j j œ œ œ j œ œ œ œ & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ™ Œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ mfœ œ J J J œ J J Trumpet 2 & 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Horn 1 & 2 in F # & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Trombone 1 & 2 ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Euphonium ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tuba ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Double Bass ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Timpani °? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Glockenspiel ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ -

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected]

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected] - www.beckyshrimpton.com Agent – Paul Smith - ETM HEIGHT: 5’5’’ WEIGHT: 140 lbs HAIR: Dark Brown EYES: Green SELECTED FILM & TELEVISION Stress Vaccine Lead Tom Mae/Tom Mae Productions Be Alert Bert – Martial Arts Lead Lisa Lovatt/ITV Be Alert Bert – Shoplifting Lead James Martins/ITV The Ghost is a Lie Lead Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Surviving Evil – Season 2 Episode 4 Principal Emily/Schooley/Laughing Cat Productions Giving You the Business Season 1 Episode 8 Principal Joel Goldberg/FoodNetwork USA Canada! Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Irresistible Force Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Mask-a-raid Principal Liza Callahan/VFS Productions Cutaway Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films The Missing Me Principal Attila Kallai/Atka Films The Drinking Helps Principal Josh Kingston/Mom's Proud Productions Tower Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films Inspiration Actor Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Films Strange Famous Music Video Actor Dustin Kuypers/The Documentarians Motives and Murders Season 5 Episode 6 Actor Cineflix Productions SELECTED ANIMATION VOICE OVER Fireman Sam Helen Flood Susan Hart/Kitchen Sync Mage and Minions Female Heroes John Welch/Making Fun Inc. Doki Multiple Characters Susan Hart/Investigation Kids Brambleberry Tales Narrator David Lam/Rival Schools Firefall Nina Ian Macmillan/VFS Productions HellBent Beatrix Samantha Satiago/Ringling Animations DecorView Kate Chad Parker/FunnelBox Media Ring Run Circus Nina Sebastian Fernandez/Kalio Productions -

Peake Studies

STUDIES Advertisements for the Brewers’ Society drawn by MERVYN PEAKE 3–18 The Writing of Titus Groan G PETER WINNINGTON 19–48 with reproductions from the MS on pages 25, 29, 31, 35 and 37 Edmund Dehn reads Titus: the ISIS cassettes reviewed by AMELIA CUDD 49 News Roundup 51 Advertisement for Jamaica Rum drawn by MERVYN PEAKE on rear cover Vol.5, no 1 Autumn 1996 STUDIES A pen-and-ink portrait by MERVYN PEAKE 5 Mirrors, Water and Smells in Titus Alone ALICE MILLS 7 Gormenghast, a Censored Fairy Tale PIERRE-Y VES LE CAM 23 The Mud Dwellings: a drawing from the manuscript of Titus Groan 26–27 A new edition of Boy in Darkness 42 Is It for Children? by DIANA WYNNE JONES 43 The Challenge of Illustrating Peake by P J LYNCH 47 News Roundup 50 Portrait of Pamela Hansford Johnson by MERVYN PEAKE on rear cover Vol. 5, no 2 Spring 1997 STUDIES A double portrait of Maeve Gilmore by MERVYN PEAKE 5 Mervyn and Maeve ANDREW HALL 7 Humour in the Titus Books JOHN DONALDSON 11 “Mervyn Peakeyweakey” – a sketch from the MS of Gormenghast by Mervyn Peake 25 The Form of Peake’s Cave G PETER WINNINGTON 28 The Minds War Made: The Faber Book of War Poetry reviewed by ADAM PIETTE 39 Recent Publications 44 News Roundup 48 Unfinished drawing of Billy Bottle by MERVYN PEAKE rear cover Vol. 5, no 3 October 1997 STUDIES Mervyn Peake and Memory CHARLES GILBERT 5 Five Illustrated Nonsense Poems by MERVYN PEAKE “One day when they had settled down” 21 “Again! again! and yet again!” 22 “Uncle George” 23 “The King of Ranga-Tanga-Roon” 24–25 “I cannot give you reasons” 26–27 Holocaust Peake by ALICE MILLS 28 Recent Publications 45 The BBC News 46 Index to Volume 5 47 “One day when they had settled down” by MERVYN PEAKE rear cover Vol. -

Key Stage Three What Could I Read Next?

Key Stage Three What could I read next? Titles marked with *** are more of a challenge read - challenge yourself to read some of these! Titles in red can be found in the LRC. Fantasy and Science-Fiction C. S. Lewis, The Chronicles of Narnia Douglas Adams, The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy *** H.G. Wells, The Time Machine Jack Finney, Invasion of the Body Snatchers J. R. R. Tolkein, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings Jules Verne, Journey to the Centre of the Earth and 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Lemony Snickett, A Series of Unfortunate Event Mervyn Peake, Gormenghast Trilogy(Titus Groan, Gormenghast &Titus Alone) P. D. James, The Children of Men Philip Pullman, His Dark Materials Trilogy (Northern Lights, The Subtle Knife & The Amber Spyglass) JK Rowling Harry Potter Series Tony Diterlizzi, The Search for Wondla Cornelia Funke, Inkdeath Philip Reeve, Goblins Eva Ibbotson, The Ogre of Oglefort Julia Golding, Secret of the Sirens AJ Lake, The coming of dragons Kenneth Grahame, The reluctant dragon Mark Robson, Firestorm Dugald Steer, The dragon's eye Templar Cressida Cowell, A hero's guide to deadly Horrendous Haddock III Philip Reeve, No such thing as dragons Kaye Umansky, The dreadful dragon Toby Forward, Dragonborn Walker Chris Mould, Fangs 'n' fire : ten dramatic dragon tales Lucinda Hare, The dragon whisperer Margaret Bateson-Hill, Dragon racer Dan Abnett, Dragon frontier Elizabeth Kay, The divide Chicken House Historical Fiction Michael Morpugo, Private Peaceful Philippa Gregory, The Other Boleyn Girl Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff Nevil Shute A Town like Alice Tracy Chavalier, The Girl with the Pearl Earing Michelle Magorian Goodnight Mister Tom Family and Relationships Sharon Creech, Heartbeat Bali Rai, (Un)Arranged Marriage Kevin Crossley Holland, Gatty’s Tale Mary Hooper, At the Sign of the Sugared Plum Tanya Landman, Apache: Girl Warrior *** J. -

Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone Ebook Free Download

THE GORMENGHAST NOVELS: TITUS GROAN / GORMENGHAST / TITUS ALONE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mervyn Laurence Peake | 1168 pages | 01 Dec 1995 | Overlook Press | 9780879516284 | English | New York, United States The Gormenghast Novels: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone PDF Book Tolkien, but his surreal fiction was influenced by his early love for Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson rather than Tolkien's studies of mythology and philology. It was very difficult to get through or enjoy this book, because it feels so very scattered. But his eyes were disappointing. Nannie Slagg: An ancient dwarf who serves as the nurse for infant Titus and Fuchsia before him. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. I honestly can't decide if I liked it better than the first two or not. So again, mixed feelings. There is no swarmer like the nimble flame; and all is over. How does this vast castle pay for itself? The emphasis on bizarre characters, or their odd characteristics, is Dickensian. As David Louis Edelman notes, the prescient Steerpike never seems to be able to accomplish much either, except to drive Titus' father mad by burning his library. At the beginning of the novel, two agents of change are introduced into the stagnant society of Gormenghast. However, it is difficult for me to imagine how such readers could at once praise Peake for the the singular, spectacular world of the first two books, and then become upset when he continues to expand his vision. Without Gormenghast's walls to hold them together, they tumble apart in their separate directions, and the narrative is a jumbled climb around a pile of disparate ruins. -

TLG to Big Reading

The Little Guide to Big Reading Talking BBC Big Read books with family, friends and colleagues Contents Introduction page 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group page 4 Book groups at work page 7 Some ideas on what to talk about in your group page 9 The Top 21 page 10 The Top 100 page 20 Other ways to share BBC Big Read books page 26 What next? page 27 The Little Guide to Big Reading was created in collaboration with Booktrust 2 Introduction “I’ve voted for my best-loved book – what do I do now?” The BBC Big Read started with an open invitation for everyone to nominate a favourite book resulting in a list of the nation’s Top 100 books.It will finish by focusing on just 21 novels which matter to millions and give you the chance to vote for your favourite and decide the title of the nation’s best-loved book. This guide provides some ideas on ways to approach The Big Read and advice on: • setting up a Big Read book group • what to talk about and how to structure your meetings • finding other ways to share Big Read books Whether you’re reading by yourself or planning to start a reading group, you can plan your reading around The BBC Big Read and join the nation’s biggest ever book club! 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group “Ours is a social group, really. I sometimes think the book’s just an extra excuse for us to get together once a month.” “I’ve learnt such a lot about literature from the people there.And I’ve read books I’d never have chosen for myself – a real consciousness raiser.” “I’m reading all the time now – and I’m not a reader.” Book groups can be very enjoyable and stimulating.There are tens of thousands of them in existence in the UK and each one is different. -

1 Introduction: the Urban Gothic of the British Home Front

Notes 1 Introduction: The Urban Gothic of the British Home Front 1. The closest material consists of articles about Elizabeth Bowen, but even in her case, the wartime work has been relatively under-explored in terms of the Gothic tradition. Julia Briggs mentions Bowen’s wartime writing briefly in her article on “The Ghost Story” (130) and Bowen’s pre-war ghost stories have been examined as Gothic, particularly her short story “The Shadowy Third”: see David Punter (“Hungry Ghosts”) and Diana Wallace (“Uncanny Stories”). Bowen was Anglo-Irish, and as such has a complex relationship to national identity; this dimension of her work has been explored through a Gothic lens in articles by Nicholas Royle and Julian Moynahan. 2. Cultural geography differentiates between “place” and “space.” Humanist geographers like Yi-Fu Tuan associate place with security and space with free- dom and threat (Cresswell 8) but the binary of space and place falls into the same traps as all binaries: one pole tends to be valorised and liminal positions between the two are effaced. I use “space” because I distrust the nostalgia that has often accreted around “place,” and because – as my discussion of post- imperial geographies will show – even clearly demarcated places are sites of incorrigibly intersecting mobilities (Chapter 2). In this I follow the cultural geographers who contend that place is constituted by reiterative practice (Thrift; Pred) and is open and hybrid (Massey). 3. George Chesney’s The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer (1871) was one of the earliest of these invasion fictions, and as the century advanced a large market for the genre emerged William Le Queux was the most prolific writer in the genre, his most famous book being The Invasion of 1910, With a Full Account of the Siege of London (1906).