Pete Seeger, 1955 – 1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger(1922 - 2013) Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger

Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger(1922 - 2013) Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger Beacon - Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger 1922-2013 Born in Munich, Germany in 1922 to an American mother and a Japanese father, Toshi Seeger, loving wife to Pete Seeger, died peacefully at home at age 91 on the 9th of July 2013. Toshi's mother gave birth July 1st, 1922 while traveling in Germany. She entered this country at six months of age and took up residence with her mother, Virginia Harper Berry from Washington D.C. and father, Takashi Ueda Ohta from Shikoku, Japan. She lived in Greenwich Village and Woodstock NY in the 1920s, 30s , and 40s. Her parents and half sister Aline Dixon were a part of the theatre community and she grew up surrounded by art and theatre. Toshi attended The Little Red School House in New York City and graduated from the High School of Music and Art in 1940. She was a community volunteer, festival organizer, writer, filmmaker, road manager, potter, loving mother, grandmother, great grandmother and aunt. She met her husband, folk singer and activist, Pete Seeger in 1939. They married in NYC in 1943, while Pete was on leave from the army. Toshi passed away eleven days shy of their 70th wedding anniversary. Toshi and Pete were partners in every sense of the word. They collaborated on everything from building their log cabin and organizing festivals big and small. This was made possible only through Toshi's tireless work, creative mind and meticulous organizational skills. Toshi served on the New York State Council of the Arts and marched with Dr. -

Pete Seegerhas Always Walked the Road Less Traveled. a Tall, Lean Fellow

Pete Seegerhas always walked the road less traveled. A tall, lean fellow with long arms and legs, high energy and a contagious joy of spjrit, he set everything in motion, singing in that magical voice, his head thrown back as though calling to the heavens, makingyou see that you can change the world, risk everything, do your best, cast away stones. “Bells of Rhymney,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” “ One Grain of Sand,” “ Oh, Had I a Golden Thread” ^ songs Right, from top: Seeger, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins and Arlo Guthrie (from left) at the Woody Guthrie Memorial Concert at Carnegie Hail, 1967; filming “Wasn’t That a Time?," a movie of the Weavers’ 19 8 0 reunion; Seeger with banjo; at Red Above: The Weavers in the early ’50s - Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman (from left). Left: Seeger singing on a Rocks, in hillside in El Colorado, 1983; Cerrito, C a l|p in singing for the early '60s. Eleanor Roosevelt, et al., at the opening of the Washington Labor Canteen, 1944; aboard the “Clearwater” on his beloved Hudson River; and a recent photo of Seeger sporting skimmer (above), Above: The Almanac Singers in 1 9 4 1 , with Woody Guthrie on the far left, and Seeger playing banjo. Left: Seeger with his mother, the late Constance Seeger. PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE COLLECTION OF HAROLD LEVENTHAL AND THE WOODY GUTHRIE ARCHIVES scattered along our path made with the Weavers - floor behind the couch as ever, while a retinue of like jewels, from the Ronnie Gilbert, Fred in the New York offices his friends performed present into the past, and Hellerman and Lee Hays - of Harold Leventhal, our “ Turn Turn Turn,” back, along the road to swept into listeners’ mutual manager. -

An Investigation of the Perceived Impact of the Inclusion of Steel Pan Ensembles in Collegiate Curricula in the Midwest

AN INVESTIGATION OF THE PERCEIVED IMPACT OF THE INCLUSION OF STEEL PAN ENSEMBLES IN COLLEGIATE CURRICULA IN THE MIDWEST by BENJAMIN YANCEY B.M., University of Central Florida, 2009 A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC School of Music, Theatre and Dance College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2014 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Kurt Gartner Abstract The current study is an in depth look of the impact of steel pan ensemble within the college curriculum of the Midwest. The goal of the study is to further understand what perceived impacts steel pan ensemble might have on student learning through the perceptions of both instructors and students. The ensemble's impact on the students’ senses of rhythm, ability to listen and balance in an ensemble, their understanding of voicing and harmony, and appreciation of world music were all investigated through both the perceptions of the students as well as the instructors. Other areas investigated were the role of the instructor to determine how their teaching methods and topics covered impacted the students' opinion of the ensemble. This includes, but is not limited to, time spent teaching improvisation, rote teaching versus Western notation, and adding historical context by teaching the students the history of the ensemble. The Midwest region was chosen both for its high density of collegiate steel pan ensembles as well as its encompassing of some of the oldest pan ensembles in the U.S. The study used an explanatory mixed methodology employing two surveys, a student version and an instructor version, distributed to the collegiate steel pan ensembles of the Midwest via the internet. -

“WOODY” GUTHRIE July 14, 1912 – October 3, 1967 American Singer-Songwriter and Folk Musician

2012 FESTIVAL Celebrating labour & the arts www.mayworks.org For further information contact the Workers Organizing Resource Centre 947-2220 KEEPING MANITOBA D GOING AN GROWING From Churchill to Emerson, over 32,000 MGEU members are there every day to keep our province going and growing. The MGEU is pleased to support MayWorks 2012. www.mgeu.ca Table of ConTenTs 2012 Mayworks CalendaR OF events ......................................................................................................... 3 2012 Mayworks sChedule OF events ......................................................................................................... 4 FeatuRe: woody guthRie ............................................................................................................................. 8 aCKnoWledgMenTs MAyWorkS BoArd 2012 Design: Public Service Alliance of Canada Doowah Design Inc. executive American Income Life Front cover art: Glenn Michalchuk, President; Manitoba Nurses Union Derek Black, Vice-President; Mike Ricardo Levins Morales Welfley, Secretary; Ken Kalturnyk, www.rlmarts.com Canadian Union of Public Employees Local 500 Financial Secretary Printing: Members Transcontinental Spot Graphics Canadian Union of Public Stan Rossowski; Mitch Podolak; Employees Local 3909 Hugo Torres-Cereceda; Rubin MAyWorkS PuBLIcITy MayWorks would also like to thank Kantorovich; Brian Campbell; the following for their ongoing Catherine Stearns Natanielle Felicitas support MAyWorkS ProgrAMME MAyWorkS FundErS (as oF The Workers Organizing Resource APrIL -

Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 4-17-1981 Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981" (1981). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 7140. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/7140 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editors debate news philosophies By Doug O’Harra of the Society of Professional Montana Kaimin Reporter Journalists about a controversy arising out of the Weekly News’ , Two nearly opposite views of reporting of the trial and senten journalism and newspaper cing, and a Missoulian colum coverage confronted one another nist’s subsequent reply several yesterday afternoon as a Mon days later. tana newspaper editor defended On Sept. 3, Daniel Schlosser, a his paper’s coverage of the trial 36-year-old Whitefish man, was and sentencing of a man con sentenced to three consecutive 15- victed of raping young boys. year terms in the Montana State Before about 70 people, packed Prison for three counts of sexual in the University of Montana assault. -

1. Matome Ratiba

JICLT Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology Vol. 7, Issue 1 (2012) “The sleeping lion needed protection” – lessons from the Mbube ∗∗∗ (Lion King) debacle Matome Melford Ratiba Senior Lecturer, College of Law University of South Africa (UNISA) [email protected] Abstract : In 1939 a young musician from the Zulu cultural group in South Africa, penned down what came to be the most popular albeit controversial and internationally acclaimed song of the times. Popular because the song somehow found its way into international households via the renowned Disney‘s Lion King. Controversial because the popularity passage of the song was tainted with illicit and grossly unfair dealings tantamount to theft and dishonest misappropriation of traditional intellectual property, giving rise to a lawsuit that ultimately culminated in the out of court settlement of the case. The lessons to be gained by the world and emanating from this dramatics, all pointed out to the dire need for a reconsideration of measures to be urgently put in place for the safeguarding of cultural intellectual relic such as music and dance. 1. Introduction Music has been and, and continues to be, important to all people around the world. Music is part of a group's cultural identity; it reflects their past and separates them from surrounding people. Music is rooted in the culture of a society in the same ways that food, dress and language are”. Looked at from this perspective, music therefore constitute an integral part of cultural property that inarguably requires concerted and decisive efforts towards preservation and protection of same from unjust exploitation and prevalent illicit transfer of same. -

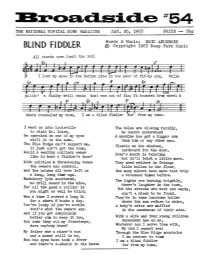

BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic

c:l.si THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE JAN. 20, 1965 PRICE -- 50¢ Words & Music: ERIC ANDERSEN BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic All chords open (omit the 3rd) there concealed my doom, I am a blind fiddler . ar from my home. I went up into Louisville The holes are closing rapidly, to visit Dr. Laine, he cannot understand He operated on one of my eyes A machine has got a bigger arm still it is the same. than him or ~ other man. The Blue Ridge can't support me, Plastic on the ,windows, it just ain't got the room, cardboard for the door, Would a wealthy colliery owner Baby's mouth is twisting like to hear a fiddler's tune? but it'll twist a little more. With politics & threatening tones They need welders in Chicago the owners can control, falls hollow to the floor, And the unions all have left us How many miners have made that trip a long, long time ago. a thousand times before. Machinery ~in scattered, The lights are burning brightly, nCOJ drill sound in the mine, there's laughter in the town, For all the good a collier is But the streets are dark and empty, you might as well be blind. ain I t a miner to be found. Was a time I worked a long 14 They're in some lonesome holler for a short 8 bucks a day. where the sun refuse to shine, You I re lucky if you're workin A baby's cries are muffled that's what the owners say. -

The Carter Family Country & Western Classics Mp3, Flac

The Carter Family Country & Western Classics mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Country & Western Classics Country: US Released: 1982 Style: Country, Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1592 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1820 mb WMA version RAR size: 1400 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 303 Other Formats: TTA FLAC AUD AA APE ASF MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits The Storms Are On The Ocean 1A Songwriter – A. P. Carter 2A It'll Aggravate Your Soul 3A Sinking In The Lonesome Sea 4A Kissing Is A Crime 5A East Virginia No.2 6A My Texas Girl 1B Gospel Ship 2B Keep On The Sunny Side 3B Lonesome Valley 4B God Gave Noah The Rainbow Sing 5B Wildwood Flower 6B Don't Forget This Song 7B Will You Miss Me When I'm Gone 1C Cannon Ball Blues 2C On The Rocks Where Moses Stood 3C I'm Thinking Tonight Of My Blue Eyes 4C Worried Man Blues 5C My Dixie Darling 6C Jealous Hearted Me 7C You've Been A Friend To Me 1D Hello Stranger 2D He Never Came Back 3D Little Joe 4D Coal Miner's Blues 5D Blackie's Gunman 6D You've Got To Righten That Wrong 1E My Home Among The Hills 2E Black Jack David 3E Bear Creek Blues 4E Beautiful Isle O'er The Sea 5E Fair And Tender Ladies 6E Sun's Gonna Shine In My Back Door 7E Railroading On The Great Divide 1F The Titanic 2F That's What It's Like To Be Lonesome 3F There's A Big Wheel 4F No More Goodbyes 5F Happiest Days Of All 6F Foggy Mountain Top Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Carter Country & Western Classics Time Life TLCW-06 TLCW-06 US 1982 Family (3xLP, Comp + Box) -

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (And More)

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (and more) First, here’s another item for consideration by people who think that Pete Seeger was anti-Israel. (If you haven’t already, read Hillel Schenker’s recent post on this.) We have the permission of Gerry Magnes — active with the Albany, NY regional J Street chapter, who married into an Israeli family — to quote what he emailed the other day: Thought I would share a small anecdote my father in law once told me. He’s 95 and still living on a kibbutz (Kibbutz Evron) in the Western Galilee. Last winter, when my wife and I mentioned to him that we’d just attended a Pete Seeger concert . in Schenectady, . he related how he’d seen him perform (I think in Tel Aviv), probably in ’64. When he [Seeger] began to speak about the Israeli-Palestinian/Arab conflict at that time and his hopes for peace, he began to cry. He had to stop talking or singing for a bit until he could collect himself. The sincerity and depth of feeling left a deep impression on my father in law. http://www.cookephoto.com/dylanovercome.html Partners’ board chair Theodore Bikel goes back a long way with Seeger. They were part of the original board (with Oscar Brand, George Wein and Albert Grossman) that founded the Newport Folk Festival. This image captures a festival high point in 1963, with Theo and Seeger (at right) joining Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, the Freedom Singers and Peter, Paul and Mary to sing “We Shall Overcome.” Here’s Theo singing Hine Ma Tov with Seeger and Rashid Hussain (the latter identified as a Palestinian poet) from episode 29 of the 39-episode run of the “Rainbow Quest” UHF television series (1965-66), dedicated to folk music and hosted by Seeger: Upon hearing of Seeger’s passing, Theo wrote this on his Facebook page: An era has come to an end. -

7. Annie's Song John Denver

Sing-Along Songs A Collection Sing-Along Songs TITLE MUSICIAN PAGE Annie’s Song John Denver 7 Apples & Bananas Raffi 8 Baby Beluga Raffi 9 Best Day of My Life American Authors 10 B I N G O was His Name O 12 Blowin’ In the Wind Bob Dylan 13 Bobby McGee Foster & Kristofferson 14 Boxer Paul Simon 15 Circle Game Joni Mitchell 16 Day is Done Peter Paul & Mary 17 Day-O Banana Boat Song Harry Belafonte 19 Down by the Bay Raffi 21 Down by the Riverside American Trad. 22 Drunken Sailor Sea Shanty/ Irish Rover 23 Edelweiss Rogers & Hammerstein 24 Every Day Roy Orbison 25 Father’s Whiskers Traditional 26 Feelin’ Groovy (59th St. Bridge Song) Paul Simon 27 Fields of Athenry Pete St. John 28 Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash 29 Forever Young Bob Dylan 31 Four Strong Winds Ian Tyson 32 1. TITLE MUSICIAN PAGE Gang of Rhythm Walk Off the Earth 33 Go Tell Aunt Rhody Traditional 35 Grandfather’s Clock Henry C. Work 36 Gypsy Rover Folk tune 38 Hallelujah Leonard Cohen 40 Happy Wanderer (Valderi) F. Sigismund E. Moller 42 Have You ever seen the Rain? John Fogerty C C R 43 He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands American Spiritual 44 Hey Jude Beattles 45 Hole in the Bucket Traditional 47 Home on the Range Brewster Higley 49 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 50 How Much is that Doggie in the Window? Bob Merrill 51 I Met a Bear Tanah Keeta Scouts 52 I Walk the Line Johnny Cash 53 I Would Walk 500 Miles Proclaimers 54 I’m a Believer Neil Diamond /Monkees 56 I’m Leaving on a Jet Plane John Denver 57 If I Had a Hammer Pete Seeger 58 If I Had a Million Dollars Bare Naked Ladies 59 If You Miss the Train I’m On Peter Paul & Mary 61 If You’re Happy and You Know It 62 Imagine John Lennon 63 It’s a Small World Sherman & Sherman 64 2. -

Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94

Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94 By Jon Pareles, The New York Times, 1/28 Pete Seeger, the singer, folk-song collector and songwriter who spearheaded an American folk revival and spent a long career championing folk music as both a vital heritage and a catalyst for social change, died Monday. He was 94 and lived in Beacon, N.Y. His death was confirmed by his grandson, Kitama Cahill Jackson, who said he died of natural causes at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Mr. Seeger’s career carried him from singing at labor rallies to the Top 10 to college auditoriums to folk festivals, and from a conviction for contempt of Congress (after defying the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s) to performing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at an inaugural concert for Barack Obama. 1 / 13 Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94 For Mr. Seeger, folk music and a sense of community were inseparable, and where he saw a community, he saw the possibility of political action. In his hearty tenor, Mr. Seeger, a beanpole of a man who most often played 12-string guitar or five-string banjo, sang topical songs and children’s songs, humorous tunes and earnest anthems, always encouraging listeners to join in. His agenda paralleled the concerns of the American left: He sang for the labor movement in the 1940s and 1950s, for civil rights marches and anti-Vietnam War rallies in the 1960s, and for environmental and antiwar causes in the 1970s and beyond. -

“Talking Union”--The Almanac Singers (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Cesare Civetta (Guest Post)*

“Talking Union”--The Almanac Singers (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Cesare Civetta (guest post)* 78rpm album package Pete Seeger, known as the “Father of American Folk music,” had a difficult time of it as a young, budding singer. While serving in the US Army during World War II, he wrote to his wife, Toshi, “Every song I started to write and gave up was a failure. I started to paint because I failed to get a job as a journalist. I started singing and playing more because I was a failure as a painter. I went into the army because I was having more and more failure musically.” But he practiced his banjo for hours and hours each day, usually starting as soon as he woke in the morning, and became a virtuoso on the instrument, and even went on to invent the “long-neck banjo.” The origin of the Almanacs Singers’ name, according to Lee Hays, is that every farmer's home contains at least two books: the Bible, and the Almanac! The Almanacs Singers’ first job was a lunch performance at the Jade Mountain Restaurant in New York in December of 1940 where they were paid $2.50! The original members of the group were Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Millard Campbell, John Peter Hawes, and later Woody Guthrie. Initially, Seeger used the name Pete Bowers because his dad was then working for the US government and he could have lost his job due to his son’s left-leaning politically charged music. The Singers sang anti-war songs, songs about the draft, and songs about President Roosevelt, frequently attacking him.