Ii WOODY GUTHRIE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

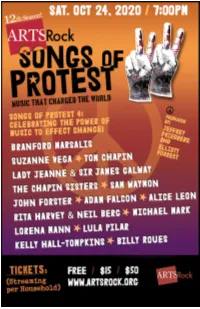

Songs-Of-Protest-2020.Pdf

Elliott Forrest Dara Falco Executive & Artistic Director Managing Director Board of Trustees Stephen Iger, President Melanie Rock, Vice President Joe Morley, Secretary Tim Domini, Treasurer Karen Ayres Rod Greenwood Simon Basner Patrick Heaphy David Brogno James Sarna Hal Coon Lisa Waterworth Jeffrey Doctorow Matthew Watson SUPPORT THE ARTS Donations accepted throughout the show online at ArtsRock.org The mission of ArtsRock is to provide increased access to professional arts and multi-cultural programs for an underserved, diverse audience in and around Rockland County. ArtsRock.org ArtsRock is a 501 (C)(3) Not For-Profit Corporation Dear Friends both Near and Far, Welcome to SONGS OF PROTEST 4, from ArtsRock.org, a non- profit, non-partisan arts organization based in Nyack, NY. We are so glad you have joined us to celebrate the power of music to make social change. Each of the first three SONGS OF PROTEST events, starting in April of 2017, was presented to sold-out audiences in our Rockland, NY community. This latest concert, was supposed to have taken place in-person on April 6th, 2020. We had the performer lineup and songs already chosen when we had to halt the entire season due to the pandemic. As in SONGS OF PROTEST 1, 2 & 3, we had planned to present an evening filled with amazing performers and powerful songs that have had a historical impact on social justice. When we decided to resume the series virtually, we rethought the concept. With so much going on in our country and the world, we offered the performers the opportunity to write or present an original work about an issue from our current state of affairs. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

Kennolyn Guitar Songbook

Kennolyn Guitar Songbook Updated Spring 2020 1 Ukulele Chords 2 Guitar Chords 3 Country Roads (John Denver) C Am Almost heaven, West Virginia, G F C Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah River. C Am Life is old there, older than the trees, G F C Younger than the mountains, blowin' like a breeze. CHORUS: C G Country roads, take me home, Am F To the place I belong. C G West Virginia, mountain momma, F C Take me home, country roads. C Am All my mem'ries gather 'round her, G F C Miner's lady, stranger to blue water. C Am Dark and dusty, painted on the sky, G F C Misty taste of moonshine, tear drop in my eye. CHORUS Am G C I hear her voice, in the mornin' hour she calls me, F C G Radio reminds me of my home far away. Am Bb F C Drivin' down the road I get the feelin' that I should G G7 Have been home yesterday, yesterday. CHORUS 4 Honey You Can’t Love One C G7 Honey you cant love one, honey, you can’t love one. C C7 F You can’t love one and still have fun C G7 C So, I’m leavin’ on the midnight train, la de da, all aboard, toot toot! two…you cant love two and still be true three… you cant love three and still love me four… you cant love ofur and still love more five…you cant love five and still survive six… you cant love six and still play tricks seven… you cant love seven and still go to heaven eight… you cant love eight and still be my date nine… you cant love nine and still be mine… ten… you cant love ten so baby kiss me again and to heck with the midnight train. -

The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography

LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations William H. Hannon Library 8-2014 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey Gatten Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Gatten, Jeffrey, "The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography" (2014). LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations. 91. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs/91 This Article - On Campus Only is brought to you for free and open access by the William H. Hannon Library at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Music and Society, 2014 Vol. 37, No. 4, 464–475, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.834749 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey N. Gatten This bibliography updates two extensive works designed to include comprehensively all significant works by and about Woody Guthrie. Richard A. Reuss published A Woody Guthrie Bibliography, 1912–1967 in 1968 and Jeffrey N. Gatten’s article “Woody Guthrie: A Bibliographic Update, 1968–1986” appeared in 1988. With this current article, researchers need only utilize these three bibliographies to identify all English- language items of relevance related to, or written by, Guthrie. Introduction Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (1912–67) was a singer, musician, composer, author, artist, radio personality, columnist, activist, and philosopher. By now, most anyone with interest knows the shorthand version of his biography: refugee from the Oklahoma dust bowl, California radio show performer, New York City socialist, musical documentarian of the Northwest, merchant marine, and finally decline and death from Huntington’s chorea. -

Conflicting Images of Land, People, and Nature of Native Americans and Euro-Americans Robert H

This Land Is Your Land, This Land Is My Land: Conflicting Images of Land, People, and Nature of Native Americans and Euro-Americans Robert H. Craig Abstract This paper explores varying dimensions of an enduring conflict between people of European origin and indigenous communities over land and land related issues. This means not only wrestling with differing understandings of land and natural world, especially as a visual landscape, but what we might learn from indigenous people that can lead to the creation of a common future that enhances both human and nonhuman life. Illustrative of some of the issues at the heart of white-Indian misunderstanding is a case-study of the conflict between Euro-Americans and the Lakota people over the Black Hills of South Dakota. The closing section of this paper concludes with an examination of the work of Wendell Berry and the myriad ways he can facilitate a needed dialogue between whites and Indians. 1. Introduction The title of this paper comes from a familiar American song composed by Woody Guthrie. The ballad was the theme song for George McGovern’s ill-fated 1972 presidential campaign and has been popularized by everyone from Pete Seeger and Peter, Paul, and Mary to United Airlines and the Ford Motor Company (Klein 1980:433). For many people this song is a romantic celebration of America that is embodied in refrains such as “from California to the New York Island, from the Redwood Forests, to the Gulf Stream waters, this land was made for you and me.” (Woody Guthrie Pages: 1). -

Chunga 12 I Learned That Mike Glicksohn and It Is a Pleasure to See Them Again

13 s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 7 “But wouldn’t it be cheaper just to use a man in a suit?” Chunga is a darkened theater where Lee Hoffman and Ron Bennett sit in the middle third row. Rich brown leans forward in the row behind them, and he won’t stop talking. Other fans are expected, and all three look over their shoulders in anticipation. In the projection booth, Bob Tucker is pouring shots from a green-labeled bottle. One for each reel change — two cartoons, a news reel, the serial chapter, the A picture, and the B picture. A pleasant odor of bourbon and popcorn fills the darkness as he throws the switch. Available by editorial whim or wistfulness, or, grudgingly, for $3.50 for a single issue; PDFs of every issue may be found at eFanzines.com. Edited by Andy ([email protected]), Randy ([email protected]), and carl ([email protected]). Please address all postal correspondence to 1013 North 36th Street, Seattle WA 98103. Editors: please send three copies of any zine for trade. In this issue . The Ascent of Hokum Art Credits A premonitory caution . 1 in order of first appearance Terminal Eyes Marc Schirmeister front cover by Andy Hooper . 2 William Rotsler 3, 26 Take the Hokum and Run (Celluloid Fantasia reprints) Stu Shiffman 7, 9, 10 by Stu Shiffman . 5 Ken Fletcher 12, 14, 15 Woody Guthrie, the Singing Sidekick by Stu Shiffman . 6 Ian Gunn 14 The Most Monstrous Show on Earth! Michael Dobson 15 (bottom), from by Bob Webber . -

This Land Is Your Land © Jake Schlapfer a Mission to Preserve You Have Inherited Vast Treasures

This Land Is Your Land © Jake Schlapfer A Mission to Preserve You have inherited vast treasures. Some of these are close at hand, and others are located at the far corners of the country. These treasures are a link to your past and a legacy to leave for the future. Every fellow citizen shares them. These treasures are your national parks—all 392 sites. They are gifts from earlier generations, set aside not for a privileged few, but for all Americans to enjoy. These varied lands hold stories that tell the tale of our nation’s development and how we have evolved. Our national parks are part of a legacy that you, too, will pass on to future generations. Two groups are among those that can help you do this: the National Park Service and the National Parks Conservation Association. The National Park Service (NPS) www.nps.gov is a government agency established in 1916 that operates under the Department of the Interior. Its purpose is to protect and preserve our National Park System. The National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) www.npca.org is an independent voice outside of government. Established in 1919, NPCA works to protect and enhance America’s national parks for current and future generations. Melissa Blair, NPCA Alaska Field Representative, with a wild silver salmon. Kenai Fjords National Park. As you can see, the two organizations have similar missions. “The mission of the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) is to conserve the scenery, the natural and historic objects, and the wildlife in the United States’ national parks, and to provide for the public’s enjoyment of these features in a manner that will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Ponder the Parks: National Parks Conservation Association’s (NPCA) mission is “To protect and enhance America’s National Park System 1. -

Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94

Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94 By Jon Pareles, The New York Times, 1/28 Pete Seeger, the singer, folk-song collector and songwriter who spearheaded an American folk revival and spent a long career championing folk music as both a vital heritage and a catalyst for social change, died Monday. He was 94 and lived in Beacon, N.Y. His death was confirmed by his grandson, Kitama Cahill Jackson, who said he died of natural causes at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Mr. Seeger’s career carried him from singing at labor rallies to the Top 10 to college auditoriums to folk festivals, and from a conviction for contempt of Congress (after defying the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s) to performing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at an inaugural concert for Barack Obama. 1 / 13 Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94 For Mr. Seeger, folk music and a sense of community were inseparable, and where he saw a community, he saw the possibility of political action. In his hearty tenor, Mr. Seeger, a beanpole of a man who most often played 12-string guitar or five-string banjo, sang topical songs and children’s songs, humorous tunes and earnest anthems, always encouraging listeners to join in. His agenda paralleled the concerns of the American left: He sang for the labor movement in the 1940s and 1950s, for civil rights marches and anti-Vietnam War rallies in the 1960s, and for environmental and antiwar causes in the 1970s and beyond. -

October 1-3, 2017 Greetings from Delta State President William N

OCTOBER 1-3, 2017 GREETINGS FROM DELTA STATE PRESIDENT WILLIAM N. LAFORGE Welcome to Delta State University, the heart of the Mississippi Delta, and the home of the blues! Delta State provides a wide array of educational, cultural, and athletic activities. Our university plays a key role in the leadership and development of the Mississippi Delta and of the State of Mississippi through a variety of partnerships with businesses, local governments, and community organizations. As a university of champions, we boast talented faculty who focus on student instruction and mentoring; award-winning degree programs in business, arts and sciences, nursing, and education; unique, cutting-edge programs such as aviation, geospatial studies, and the Delta Music Institute; intercollegiate athletics with numerous national and conference championships in many sports; and a full package of extracurricular activities and a college experience that help prepare our students for careers in an ever-changing, global economy. Delta State University’s annual International Conference on the Blues consists of three days of intense academic and scholarly activity, and includes a variety of musical performances to ensure authenticity and a direct connection to the demographics surrounding the “Home of the Delta Blues.” Delta State University’s vision of becoming the academic center for the blues — where scholars, musicians, industry gurus, historians, demographers, and tourists come to the “Blues Mecca” — is becoming a reality, and we are pleased that you have joined us. I hope you will engage in as many of the program events as possible. This is your conference, and it is our hope that you find it meaningful. -

“Talking Union”--The Almanac Singers (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Cesare Civetta (Guest Post)*

“Talking Union”--The Almanac Singers (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Cesare Civetta (guest post)* 78rpm album package Pete Seeger, known as the “Father of American Folk music,” had a difficult time of it as a young, budding singer. While serving in the US Army during World War II, he wrote to his wife, Toshi, “Every song I started to write and gave up was a failure. I started to paint because I failed to get a job as a journalist. I started singing and playing more because I was a failure as a painter. I went into the army because I was having more and more failure musically.” But he practiced his banjo for hours and hours each day, usually starting as soon as he woke in the morning, and became a virtuoso on the instrument, and even went on to invent the “long-neck banjo.” The origin of the Almanacs Singers’ name, according to Lee Hays, is that every farmer's home contains at least two books: the Bible, and the Almanac! The Almanacs Singers’ first job was a lunch performance at the Jade Mountain Restaurant in New York in December of 1940 where they were paid $2.50! The original members of the group were Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Millard Campbell, John Peter Hawes, and later Woody Guthrie. Initially, Seeger used the name Pete Bowers because his dad was then working for the US government and he could have lost his job due to his son’s left-leaning politically charged music. The Singers sang anti-war songs, songs about the draft, and songs about President Roosevelt, frequently attacking him. -

Folk Music, Internal Migration, and the Cultural Left

Internal Migration and the Left Futures That Internal Migration Place-Specifi c Introduction Never Were and the Left Material Resources THE SOUTH AND THE MAKING OF THE AMERICAN OTHER: FOLK MUSIC, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND THE CULTURAL LEFT Risto Lenz In 1940, actor and activist Will Geer organized the “Grapes of Wraths Evening,” a benefi t concert for the John Steinbeck Committee for Agricultural Workers at Forrest Theater in New York City. The pro- gram served as a blueprint for what would later defi ne the American folk music revival: Urban Northerners sharing the stage with “authentic” rural Southerners, together celebrating America’s musical heritage in a politically charged framework (here: helping migrant farmwork- ers). Among the “real” folk were Aunt Molly Jackson, an organizer for the Kentucky coal mines and a singer of union songs, Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, an African American songster from Louisiana, and Woody Guthrie, a singer from Oklahoma. The three musicians, 1 He is sometimes also who would all spend their subsequent lives in New York as well as referred to as “Leadbelly.” in California, represent the three main migration fl ows of Southerners Both spellings are pos- sible. I will hereaft er use moving out of farms and towns of the American South in great “Lead Belly” since it was numbers and into cities and suburbs of the North and the West: The the preferred spelling of the singer himself as 1 Great Migration of black Southerners (Lead Belly ), the dust bowl well as of the Lead Belly migration (Guthrie), and the Appalachian migration (Jackson).2 The Foundation.