Implementation of HPV-Based Cervical Cancer Screening Combined with Self-Sampling Using a Midwifery Network Across Rural Greece. the GRECOSELF Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visualizing the Byzantine City the Art of Memory

Abstracts Visualizing the Byzantine City Charalambos Bakirtzis Depictions of cities: in the icon “Allegory of Jerusalem on High,” two cities are depicted, one in the foothills and the other at the edge of a rocky mountain. The lengthy inscription of the icon is of interest from a town-planning and architectural standpoint. The imperial Christian city: in the mosaics of the Rotunda in Thessalonike, the city is not shown with walls, but with palaces and other splendid public buildings, declaring the emperor’s authority as the sole ruler and guarantor of the unity of the state and the well-being of cities, which was replaced by the authority of Christ. The appearance of the walled city: all the events shown in the mosaics (seventh century) of the basilica of St. Demetrios are taking place outside the walls of the city, probably beside the roads that lead to it. The city’s chora not only protected the city; it was also protected by it. A description of the city/kastron: John Kameniates lived through the capture of Thessalonike by the Arabs in the summer of 904. At the beginning of the narrative, he prefixes a lengthy description/encomium of Thessalonike. The means of approaching the place indicate that the way the city is described by Kameniates suits a visual description. Visualizing the Late Byzantine city: A. In an icon St. Demetrios is shown astride a horse. In the background, Thessalonike is depicted from above. A fitting comment on this depiction of Thessalonike is offered by John Staurakios because he renders the admiration called forth by the large Late Byzantine capitals in connection with the abandoned countryside. -

Results Factsheet Indicator Tra05: Time-Distance

April 2008 RESULTS FACTSHEET INDICATOR TRA05: TIME-DISTANCE DEFINITION- OBJECTIVE The indicator assesses the time-distances within the Impact Zone of the Egnatia Motorway, when using means of road transport. The distance time between cities is an essential indicator for the assessment of the cities’ accessibility and a basic piece of information, as regards the cost calculation for the transportation of goods and the overall cost. RESULTS – ASSESSMENT With the help of the counts available and traffic model of EGNATIA ODOS SA, three maps (2, 3 & 4) of time zones have been prepared, showing the reduction of the time-distance assessed, which will be achieved for movements from Ioannina, Kozani, Thessalonki and Komotini to other areas with the completion of the motorway, in relation to the situation prior to the Egnatia Motorway construction. Generally, the completion of the Egnatia Motorway construction will result in a substantial saving of the time required to travel along Northern Greece. In particular, the route Ioannina - Thessaloniki will be reduced by approximately 3 hours, Ioannina - Komotini more than 4 hours, while the route Ioannina - Igoumenitsa will be reduced by 1 hour and the distance Ioannina- Kipi will be reduced by more than 4 hours. The time required for the route Kozani - Ioannina will be reduced by 1 hour, Kozani – Ioannina more than 90 minutes, Kozani - Komotini more than 2 hours, while the routes of Kozani - Igomenitsa and Kozani - Kipi will be reduced by up to 3 hours. The time required for the route Thessaloniki- Igoumenitsa will be reduced by more than 3 hours, while the journey Thessaloniki- Kipi (Greek - Turkish borders) will be reduced by 2 hours. -

Name Address Postal City Mfi Id Head Office Res* Greece

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE RES* GREECE Central Banks GR010 Bank of Greece, S.A. 21, Panepistimiou Str. 102 50 Athens No Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions GR060 ABN Amro Bank 348, Syngrou Avenue 176 74 Athens NL ABN AMRO Bank N.V. Yes GR077 Achaiki Co-operative Bank, L.L.C. 66, Michalakopoulou Str. 262 21 Patra Yes GR056 Aegean Baltic Bank S.A. 28, Diligianni Str. 145 62 Athens Yes GR014 Alpha Bank, S.A. 40, Stadiou Str. 102 52 Athens Yes GR100 American Bank of Albania Greek Branch 14, E. Benaki Str. 106 78 Athens AL American Bank of Albania Yes GR080 American Express Bank 280, Kifissias Avenue 152 32 Athens US American Express Yes Company GR047 Aspis Bank S.A. 4, Othonos Str. 105 57 Athens Yes GR043 ATE Bank, S.A. 23, Panepistimiou Str. 105 64 Athens Yes GR016 Attica Bank, S.A. 23, Omirou Str. 106 72 Athens Yes GR081 Bank of America N.A. 35, Panepistimiou Str. 102 27 Athens US Bank of America Yes Corporation GR073 Bank of Cyprus Limited 170, Alexandras Avenue 115 21 Athens CY Bank of Cyprus Public Yes Company Ltd GR050 Bank Saderat Iran 25, Panepistimiou Str. 105 64 Athens IR Bank Saderat Iran Yes GR072 Bayerische Hypo und Vereinsbank A.G. 7, Irakleitou Str. 106 73 Athens DE Bayerische Hypo- und Yes Vereinsbank AG GR105 BMW Austria Bank GmbH Zeppou 33 166 57 Athens AT BMW Austria Bank GmbH Yes GR070 BNP Paribas 94, Vas. Sofias Avenue 115 28 Athens FR Bnp paribas Yes GR039 BNP Paribas Securities Services 94, Vas. -

SOS Children's Villages

Pre-school Educa/on of Children in Migra/on in Greece Ioannina – Greece Program summary Since October 2020, SOS Children’s Villages runs a kindergarten in Ioannina (Greece) to support refugee and migrant children and their families in their development, their mental health, their social interacBons and their integraBon in the Greek community. This project aims to support and care for preschool aged children and their families through preschool educaBonal acBviBes and psychosocial support. Background informa/on on refugees and asylum-seekers in Greece At the end of 2019, Greece hosted over 186.000 refugees and asylum-seekers. This included over 5.000 unaccompanied children. Most people were coming from Afghanistan, the Syrian Arab Republic, the DemocraBc Republic of the Congo and Iran. Sub-standard recepBon condiBons, overcrowded first-line recepBon faciliBes, as well as limited access to psychosocial support, case management, care, protecBon, health, immunizaBon and slow asylum and administraBve procedures remain the most common issues faced by refugee and migrant children and their families on the ground. Despite notable progress in naBonal legislaBve and policy framework related to the protecBon of refugee children, and overall inclusion into naBonal educaBon systems, naBonal capaciBes to respond to the needs of some of the most vulnerable children on the move (e.g. living in squats and informal seSlements in urban areas, potenBal vicBms of Gender Based Violence, as well as in detenBon or in first idenBficaBon and recepBon centres in Greek islands) are limited, requiring addiBonal investments and technical support. On top of that, some of the current support interven/ons have been downsized, which will affect the livelihood of 10.685 people of concern, either forcing them to leave their accommodaBon or leaving them without cash assistance. -

Greek Cultures, Traditions and People

GREEK CULTURES, TRADITIONS AND PEOPLE Paschalis Nikolaou – Fulbright Fellow Greece ◦ What is ‘culture’? “Culture is the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts […] The word "culture" derives from a French term, which in turn derives from the Latin "colere," which means to tend to the earth and Some grow, or cultivation and nurture. […] The term "Western culture" has come to define the culture of European countries as well as those that definitions have been heavily influenced by European immigration, such as the United States […] Western culture has its roots in the Classical Period of …when, to define, is to the Greco-Roman era and the rise of Christianity in the 14th century.” realise connections and significant overlap ◦ What do we mean by ‘tradition’? ◦ 1a: an inherited, established, or customary pattern of thought, action, or behavior (such as a religious practice or a social custom) ◦ b: a belief or story or a body of beliefs or stories relating to the past that are commonly accepted as historical though not verifiable … ◦ 2: the handing down of information, beliefs, and customs by word of mouth or by example from one generation to another without written instruction ◦ 3: cultural continuity in social attitudes, customs, and institutions ◦ 4: characteristic manner, method, or style in the best liberal tradition GREECE: ANCIENT AND MODERN What we consider ancient Greece was one of the main classical The Modern Greek State was founded in 1830, following the civilizations, making important contributions to philosophy, mathematics, revolutionary war against the Ottoman Turks, which started in astronomy, and medicine. -

Municipality of Ioannina Responds to COVID -19 Ensuring the Protection of Human Rights

Municipality of Ioannina responds to COVID -19 ensuring the protection of human rights. Dionysia Ampatzidi Advisor to the Mayor of Ioannina on social and migration policy The city of Ioannina • Capital of the Epirus region • 112.486 inhabitants • Diverse economy focused mainly on food production, tourism and education • General Hospital and University Hospital • University • Prison Photo by: ManisGeo Location of Ioannina Response to COVID-19 Create a management mechanism Create a helpline Enhance the mobile units of the Help at Home programme Ensuring the protection of the most vulnerable population ❖ Provide shelter and psychosocial support to homeless people who do not fulfil the criteria of homeless dormitory such as addicted to alcohol, drugs, and people with active mental illness ❖ Provide personal protective equipment and food assistance to the local prison ❖ Support the distribution, door to door, of food and basic materials to beneficiaries of the Greek Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived programme Roma ➢ Raise awareness about prevention and response to COVID-19 to Roma ➢ record and cover their needs ➢ provide personal protective equipment, hygiene items and food items ➢ disinfection Migrants/ refugees /asylum seekers 1/2 TOTAL POPULATION BREAKDOWN SITE / TOTAL NUMBER OF PoCs ACCOMMODATED Source: SMS, NATIONALITY ACCOMODATION PARTNER AP 35.0% KATSIKAS 1173 (incl. 18 unregistered) 28.8% 28.1% DOLIANA 144 30.0% FILIPPIADA 654 25.0% 21.9% 21.1% INTERSOS ACCOMMODATION 552 20.0% AGIA ELENI 328 SN ACCOMMODATION 262 15.0% AGIA ELENI safe zone (ARSIS) 27 10.0% ILIACHTIDA (PERAMA) 38 ICSD (PERAMA) 35 UAMs HOTELS ARSIS (PERAMA) 25 ICSD (IGOUMENITSA) 36 5.0% LYGIA 139 KANALI 86 0.0% IOM FILOXENIA HOTELS KONITSA 131 KASTROSYKIA 24 Syrian Arab Afghanistan Other (38) Iraq SELF-ACCOMMODATED 252 Republic TOTAL: 3906 LEGAL STATUS Asylum Seeker, 81% Refugee, 19% Migrants/ refugees /asylum seekers 2/2 • Raised awareness about prevention and response to COVID-19 to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in urban settings and in camp. -

Welcome to Ioannina a Multicultural City…

Welcome to Ioannina The city of Giannina, attraction of thousands of tourists every year from Greece and around the world, awaits the visitor to accommodate him with the Epirus known way, suggesting him to live a unique combination of rich past and impressive present. Built next to the legendary lake Pamvotis at 470 meters altitude, in the northwest of Greece, it is the biggest city of Epirus and one of the most populous in the country. History walks beside you through the places, the impressive landscape that combines mountain and water, museums with unique exhibits and monuments also waiting to lead you from the Antiquity to the Middle Byzantine and Late Byzantine period, the Turks, Modern History. And then ... the modern city with modern structures (University, Hospital, Airport, Modern Highway - Egnatia - Regional, local and long distance transportation, Spiritual and Cultural Centres) offer a variety of events throughout the year. Traditional and modern market, various entertainment options, dining and accommodation. A multicultural city… Ioannina arise multiculturally and multifacetedly not only through narrations. Churches with remarkable architecture, mosques and a synagogue, the largest in Greece, testify the multicultural character of the city. The coexistence of Christians, Muslims and Jews was established during the administration of Ali Pasha. The population exchange after the Minor Asia destruction and annihilation of most Jews by the Germans changed the proportions of the population. Muslims may not exist today and the Jews may be few, only those who survived the concentration camps, but the city did not throw off this part of the identity. Today, there are four mosques, three of them very well preserved, while the Jewish synagogue, built in 1826, continues to exist and be the largest and most beautiful of the surviving religious buildings of the Greek Jews. -

Oecd (Tax & Benefits)

OECD - Social Policy Division - Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Country chapter - Benefits and Wages (www.oecd.org/els/social/workincentives) ------ GREECE 2006 1. Review of the system 1.1. Average Worker Wage (AW) For the year 2006 the average gross income of a worker is 153011 Euro. 2. Unemployment Insurance The unemployment insurance system covers persons who are insured against diseases with a social insurance body. The benefits are divided into regular benefits and special allowances. This programme is targeted on employees that became unemployed against their will and are not capable of finding a job relevant to their qualifications. 2.1 Condition for receipt The person must be capable of and available for work The person must be unemployed unwillingly The person must have registered with an employment agency. The person must not receive a pension equal to or larger than the minimum pension granted by IKA (Social Insurance Institute) The person must not be self-employed. 2.1.1 Employment conditions 125 days of employment in the last 14 months prior to applying for the benefit, or 200 days of employment in the last two years prior to applying for the benefit The persons applying for the benefit for the first time must have worked for at least 80 days per year in the last two years prior to their application. 2.1.2 Contributions conditions The system is contributory. The contributions made to the OAED (Manpower Employment Organization) are paid both by the employer and the employee. 2.2 Calculation of benefit amount 2.2.1 Calculation of gross benefit Article 12 of Act 2224/94 stipulates that: “The basic benefit amounts to 40% of the daily wage or, in case of salaried employees, to 50% of their salary, on condition that the benefit will not be less than 2/3 of the daily wage of the unskilled worker or larger than the amount each time defined by Decision of the Minister of Employment, upon recommendation made by the Administration of the OAED”. -

CJ3 Logistics Package V2

www.cuncr.org Corfu & 22-26 Epirus, July 2019 Greece CLIMATECLIMATE JUSTICEJUSTICE IIIIII INTERNATIONAL SUMMIT AND AMBASSADOR TRAINING LOGISTICSLOGISTICS PACKAGEPACKAGE IN CORFU: We have arranged for blocks of rooms to be reserved at the Hotel Konstantinoupolis and the Arcadion Hotel. If you select a package that includes accommodation, we will take care of your booking at one of these hotels. The conference on Monday will be held at the Corfu city hall. Both the hotels and the city hall are located in the city center. If you wish to make arrangements to stay in a different hotel, we recommend you also find accommodation in this same area. Free TENT SPACE for a limited number of attendees! Email us: [email protected] IN EPIRUS: Attendees who choose the payment package that includes all accommodation and amenities will be staying at the Zagori Suites, a luxury hotel located in Vitsa, just down the road from our conference venue. “The all-suite boutique hotel, Zagori Suites, welcomes you to a retreat into the luxurious elegance. Located in Vitsa, at the center of Zagori, next to Vikos Gorge and the beautiful river of Voidomatis is open all year round, winter and summer. This aesthetic hotel is privileged to offer breathtaking views to the majestic landscape of Zagori. Its central location makes it ideal to become your starting point to explore the mountain paradise of Zagorohoria!” If you wish to book lodgings elsewhere, you may also consider looking in the nearby village of Monodendri. The seminar facilities (indoor and outdoor), are located at the village of Vitsa, in Zagori/Epirus, Greece, with the closest town being the lake city of Ioannina (about 45 min. -

15 the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences

LAND COVER CHANGE IN THREE SELECTED AREAS UNDER DIRECT INFLUENCE OF THE “EGNATIA” HIGHWAY, IN GREECE. A. Stamou a, Ch. Georgiadis b, P. Patias c a PhD Candidate, Dept. Cadastre, Photogrammetry and Cartography, AUTH, [email protected] b PhD, Dept. Cadastre, Photogrammetry and Cartography, AUTH, [email protected] c Professor, Dept. Cadastre, Photogrammetry and Cartography, AUTH, [email protected] Youth Forum KEY WORDS: Satellite Remote Sensing, Land Use, Digital Photogrammetry, Change Detection, Thematic Mapping ABSTRACT: The Egnatia highway, a modern closed motorway 670 kilometres long, is one of the largest road construction projects in Europe, running across Northern Greece. In order to record and analyze the spatial and environmental effects that inevitably the Egnatia highway has caused to its surroundings, the need for effective and efficient integration of land cover dynamic information is becoming more and more essential. Facing this need, this project aims at the analysis of multi-temporal spaceborne images for the detection of land cover changes in selected areas under direct influence of the Egnatia highway. This is accomplished with the estimation of two specific impact indicators, in order to assess the interaction between the Egnatia road axis and the developmental procedure and physical planning in its impact area. The first indicator monitors the pressure for land use changes that have occurred over the decade 1998-2007, and the second monitors the changes in residential areas for the same period of time. The data used are for the base year 1998: three multispectral orthoimages SPOT, with spatial analysis 20 m, and for the check year 2007: three synthetic images IKONOS, with spatial analysis 1 m. -

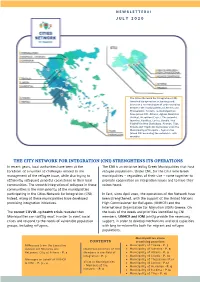

The City Network for Integration (Cni) Strenghtens Its Operations

N E W S L E T T E R # 1 J U L Y 2 0 2 0 The Cities Network for Integration (CNI) launched its operation in January 2018, based on a memorandum of understanding between the municipalities of Athens and Thessaloniki. To date, 14 municipalities have joined CNI: Athens, Aghios Dimitrios (Attica), Heraklion (Crete), Thessaloniki, Ioannina, Karditsa, Larisa, Livadia, Nea Filadelfeia/Nea Chalkidona, Piraeus, Tilos, Trikala and Tripoli.On September 2020 the Municipality of Neapolis - Sykeon has joined CNI becoming the network's 14th member. THE CITY NETWORK FOR INTEGRATION (CNI) STRENGHTENS ITS OPERATIONS In recent years, local authorities have been at the The CNI is an initiative led by Greek Municipalities that host forefront of a number of challenges related to the refugee populations. Under CNI, for the first time Greek management of the refugee issue, while also trying to municipalities – regardless of their size – come together to efficiently safeguard peaceful coexistence in their local promote cooperation on integration issues and to have their communities. The smooth integration of refugees in these voices heard. communities is the main priority of the municipalities participating in the Cities Network for Integration (CNI). In fact, since April 2020, the operations of the Network have Indeed, many of these municipalities have developed been strengthened, with the support of the United Nations promising integration initiatives. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Greece. On The recent COVID-19 health crisis revealed that the basis of the needs and priorities identified by CNI Municipalities can swiftly react in order to avert social members, UNHCR and IOM jointly provide the necessary crises and respond to the needs of vulnerable population support, in order to develop mechanisms and local capacities groups, including refugees. -

Optitrans Baseline Study Thessaly

OPTITRANS BASELINE STUDY THESSALY Version 1.0 Date: February 2019 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2 Population and Territorial Characteristics ............................................................................................. 6 2.1 Regional Unit of Larissa ................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Regional Unit of Trikala ................................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Regional Unit of Karditsa .............................................................................................................. 11 2.4 Regional Unit of Magnesia ........................................................................................................... 12 2.5 Regional Unit of Sporades ........................................................................................................... 13 3 Mobility and Transport Infrastructure ................................................................................................... 14 3.1 Road Transport ............................................................................................................................. 14 3.2 Rail Transport ............................................................................................................................... 17 3.3 Sea Transport ..............................................................................................................................