Hearst and Marion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Sky Dragon Tour 龍之旅

Sky Dragon Tour 龍之旅 Day 1: Los Angeles - Yosemite National Park Morning departure to California's most famous National Park. As one of the masterpieces of nature, Yosemite near the geographical center of the Sierra Nevada. Towering granite rocks, magnificent waterfalls and tranquil valley, making Yosemite from any angle looks like a fairyland in general. Giant trees, mountains and streams, glaciers have carved huge rocks and cliffs and sparkling lake. There is no doubt that the liquid and solid water in both its main hero Yosemite magnificent landscape. Here you can see the world's largest intact blocks of granite - Captain Rock (El Captain) and Yosemite Falls (Yosemite Waterfall), scenic spots in the tunnel (Tunnel View Point) can also see Seven Wonders of the semicircle Hill (Half Dome) *In case of unforeseen winter snow season, we will replace Yosemite with 17 miles schedule. Hotel: Holiday Inn Express or Similar Day 2: San Francisco City Tour Morning drive to the West Coast's most prestigious public universities one of then been University of California at Berkeley, Then visit to San Francisco magnificent Palace of Fine Arts, Golden Gate Bridge and Fisherman's Wharf. However You can take a Boat tour (Optional) San Francisco Bay, close contact Treasure Island, Angel Island, Alcatraz Island, under the Golden Gate Bridge down to visit the beautiful scene of the Golden Gate Bridge and the historic fortress of defense, followed by a visit along the coastline San Francisco and overview the various attractions of history and landscape of San Francisco. In the afternoon proceed to the San Francisco extended experience Tour (Fee Required) and visit -St. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MARCH 2021 Ho u The 39 Steps (1935) 3/5 c Blondie of the Follies (1932) 3/2 Czechoslovakia on Parade (1938) 3/27 a ADVENTURE u 6,000 Enemies (1939) 3/5 u Blood Simple (1984) 3/19 z Bonnie and Clyde (1967) 3/30, 3/31 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––– c COMEDY A D Born to Love (1931) 3/16 m Dancing Lady (1933) 3/23 a Adventure (1945) 3/4 D Bottles (1936) 3/13 D Dancing Sweeties (1930) 3/24 z CRIME a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) 3/23 P c The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954) 3/26 m The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950) 3/17 a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 3/9 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 3/4 w The Dawn Patrol (1938) 3/1 o DOCUMENTARY R The Age of Consent (1932) 3/10 h Brainstorm (1983) 3/30 P D Death’s Fireworks (1935) 3/20 D All Fall Down (1962) 3/30 c Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 3/18 m The Desert Song (1943) 3/3 D DRAMA D Anatomy of a Murder (1959) 3/20 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 3/27 R Devotion (1946) 3/9 m Anchors Aweigh (1945) 3/9 P R Brief Encounter (1945) 3/25 D Diary of a Country Priest (1951) 3/14 e EPIC D Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958) 3/3 P Hc Bring on the Girls (1937) 3/6 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 3/18 c Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) 3/20 m Broadway to Hollywood (1933) 3/24 D Doom’s Brink (1935) 3/6 HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION R The Angel Wore Red (1960) 3/21 z Brute Force (1947) 3/5 D Downstairs (1932) 3/6 D Anna Christie (1930) 3/29 z Bugsy Malone (1976) 3/23 P u The Dragon Murder Case (1934) 3/13 m MUSICAL c April In Paris -

California State Parks

1 · 2 · 3 · 4 · 5 · 6 · 7 · 8 · 9 · 10 · 11 · 12 · 13 · 14 · 15 · 16 · 17 · 18 · 19 · 20 · 21 Pelican SB Designated Wildlife/Nature Viewing Designated Wildlife/Nature Viewing Visit Historical/Cultural Sites Visit Historical/Cultural Sites Smith River Off Highway Vehicle Use Off Highway Vehicle Use Equestrian Camp Site(s) Non-Motorized Boating Equestrian Camp Site(s) Non-Motorized Boating ( Tolowa Dunes SP C Educational Programs Educational Programs Wind Surfing/Surfing Wind Surfing/Surfing lo RV Sites w/Hookups RV Sites w/Hookups Gasquet 199 s Marina/Boat Ramp Motorized Boating Marina/Boat Ramp Motorized Boating A 101 ed Horseback Riding Horseback Riding Lake Earl RV Dump Station Mountain Biking RV Dump Station Mountain Biking r i S v e n m i t h R i Rustic Cabins Rustic Cabins w Visitor Center Food Service Visitor Center Food Service Camp Site(s) Snow Sports Camp Site(s) Geocaching Snow Sports Crescent City i Picnic Area Camp Store Geocaching Picnic Area Camp Store Jedediah Smith Redwoods n Restrooms RV Access Swimming Restrooms RV Access Swimming t Hilt S r e Seiad ShowersMuseum ShowersMuseum e r California Lodging California Lodging SP v ) l Klamath Iron Fishing Fishing F i i Horse Beach Hiking Beach Hiking o a Valley Gate r R r River k T Happy Creek Res. Copco Del Norte Coast Redwoods SP h r t i t e s Lake State Parks State Parks · S m Camp v e 96 i r Hornbrook R C h c Meiss Dorris PARKS FACILITIES ACTIVITIES PARKS FACILITIES ACTIVITIES t i Scott Bar f OREGON i Requa a Lake Tulelake c Admiral William Standley SRA, G2 • • (707) 247-3318 Indian Grinding Rock SHP, K7 • • • • • • • • • • • (209) 296-7488 Klamath m a P Lower CALIFORNIA Redwood K l a Yreka 5 Tule Ahjumawi Lava Springs SP, D7 • • • • • • • • • (530) 335-2777 Jack London SHP, J2 • • • • • • • • • • • • (707) 938-5216 l K Sc Macdoel Klamath a o tt Montague Lake A I m R National iv Lake Albany SMR, K3 • • • • • • (888) 327-2757 Jedediah Smith Redwoods SP, A2 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • (707) 458-3018 e S Mount a r Park h I4 E2 t 3 Newell Anderson Marsh SHP, • • • • • • (707) 994-0688 John B. -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

OLD TIME RADIO MASTER CATALOGUE.Xlsx

1471 PREVIEW THEATER OF THE AIR ZORRO-TO TRAP A FOX 15 VG SYN 744 101ST CHASE AND SANDBORN SHOW ANNIVERSARY SHOW NBC 60 EX COM 2951 15 MINUTES WITH BING CROSBY #1 1ST SONG JUST ONE MORE CHANCE 9/2/1931 8 VG SYN 4068 1949 HEART FUND THE PHIL HARRIS-ALICE FAYE SHOW 00/00/1949 15 VG COM 588 20 QUESTIONS 4/6/1946 30 VG- 592 20 QUESTIONS WET HEN MUT. 30 VG- 2307 2000 PLUS THE ROCKET AND THE SKULL 30 VG- SYN 2308 2000 PLUS A VETRAN COMES HOME 30 VG- SYN 3656 21ST PRECINCT LAST SHOW 4/20/1955 30 VG- COM 4069 A & P GYPSIES 1ST SONG IT'S JUST A MEMORY 00/00/1933 NBC 37 VG+ 1017 A CHRISTMAS PLAY #325 THESE THE HUMBLE (SCRATCHY) 30 G-VG SYN 2003 A DATE WITH JUDY WITH JOSEPH COTTON 2/6/1945 NBC 30 VG COM 938 A DATE WITH JUDY #86 WITH CHARLES BOYER AFRS 30 VG AFRS 2488 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH MARLENA DETRICH 10/15/1942 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2489 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LUCILLE BALL 11/18/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4071 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LYNN BARI 12/16/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 4072 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE ANDREW SISTERS 12/26/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 2490 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH BERT GORDON 12/30/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2491 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH JUDY GARLAND 1/6/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2492 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH HAROLD PERRY 1/20/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4073 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE GREAT GILDERSLEEVE 1/20/1944 NBC 30 VG COM 2493 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH DOROTHY LAMOUR 2/17/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4074 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH HEDDA HOPPER 3/2/1944 NBC 30 VG COM 4075 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH BLONDIE AND DAGWOOD 3/9/1944 NBC 30 VG COM 4076 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH -

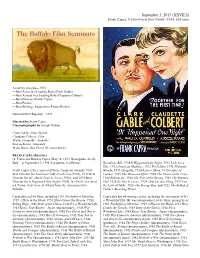

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 Min)

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 min) Academy Awards—1935: —Best Actor in a Leading Role (Clark Gable) —Best Actress in a Leading Role (Claudette Colbert) —Best Director (Frank Capra) —Best Picture —Best Writing, Adaptation (Robert Riskin) National Film Registry—1993 Directed by Frank Capra Cinematography by Joseph Walker Clark Gable...Peter Warne Claudette Colbert...Ellie Walter Connolly...Andrews Roscoe Karns...Shapeley Ward Bond...Bus Driver #1 (uncredited) FRANK CAPRA (director) (b. Francesco Rosario Capra, May 18, 1897, Bisacquino, Sicily, Italy—d. September 3, 1991, La Quinta, California) Broadway Bill, 1934 It Happened One Night, 1933 Lady for a Day, 1932 American Madness, 1932 Forbidden, 1931 Platinum Frank Capra is the recipient of three Academy Awards: 1939 Blonde, 1931 Dirigible, 1930 Rain or Shine, 1930 Ladies of Best Director for You Can't Take It with You (1938), 1937 Best Leisure, 1929 The Donovan Affair, 1928 The Power of the Press, Director for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and 1935 Best 1928 Submarine, 1928 The Way of the Strong, 1928 The Matinee Director for It Happened One Night (1934). In 1982 he received Idol, 1928 So This Is Love?, 1928 That Certain Thing, 1927 For a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film the Love of Mike, 1926 The Strong Man, and 1922 The Ballad of Institute. Fisher's Boarding House. Capra directed 54 films, including 1961 Pocketful of Miracles, Capra also has 44 writing credits, including the screenplay of It’s 1959 A Hole in the Head, 1951 Here Comes the Groom, 1950 a Wonderful Life. -

The Victor Black Label Discography

The Victor Black Label Discography Victor 25000, 26000, 27000 Series John R. Bolig ISBN 978-1-7351787-3-8 ii The Victor Black Label Discography Victor 25000, 26000, 27000 Series John R. Bolig American Discography Project UC Santa Barbara Library © 2017 John R. Bolig. All rights reserved. ii The Victor Discography Series By John R. Bolig The advent of this online discography is a continuation of record descriptions that were compiled by me and published in book form by Allan Sutton, the publisher and owner of Mainspring Press. When undertaking our work, Allan and I were aware of the work started by Ted Fa- gan and Bill Moran, in which they intended to account for every recording made by the Victor Talking Machine Company. We decided to take on what we believed was a more practical approach, one that best met the needs of record collectors. Simply stat- ed, Fagan and Moran were describing recordings that were not necessarily published; I believed record collectors were interested in records that were actually available. We decided to account for records found in Victor catalogs, ones that were purchased and found in homes after 1901 as 78rpm discs, many of which have become highly sought- after collector’s items. The following Victor discographies by John R. Bolig have been published by Main- spring Press: Caruso Records ‐ A History and Discography GEMS – The Victor Light Opera Company Discography The Victor Black Label Discography – 16000 and 17000 Series The Victor Black Label Discography – 18000 and 19000 Series The Victor Black