Illuminations Volume 11 | 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campfire Songs

Antelope Books In collaboration with W1-609-17-2 Productions Antelope Books In collaboration with W1-609-17-2 Productions Four Reasons to Sing Loud SCOUT OATH 1. If God gave you a good voice, sing loud. On my honor, I will do my best He deserves to hear it. To do my duty to God and my country And to obey the Scout Law; 2. If God gave you a good voice, sing loud. To help other people at all times; We deserve to hear it. To keep myself physically strong, 3. If God did not give you a beautiful singing voice, sing loud. Mentally awake and morally straight. Who is man to judge what God has given you? SCOUT LAW OUTDOOR CODE 4. If God did not give you a beautiful singing voice, sing out A Scout is: As an American loud, sing out strong… God deserves to hear it. Trustworthy I will do my best to - He has no one to blame but Himself! Loyal Be clean in my outdoor manners Helpful Be careful with fire Friendly Be considerate in the outdoors Courteous Be conservation minded Kind Obedient SCOUT MOTTO Cheerful Be prepared! Thrifty Brave SCOUT SLOGAN Clean Do a good turn daily! Reverent Four Reasons to Sing Loud SCOUT OATH 1. If God gave you a good voice, sing loud. On my honor, I will do my best He deserves to hear it. To do my duty to God and my country And to obey the Scout Law; 2. If God gave you a good voice, sing loud. -

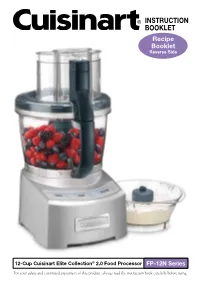

INSTRUCTION BOOKLET Recipe Booklet Reverse Side

INSTRUCTION BOOKLET Recipe Booklet Reverse Side 12-Cup Cuisinart Elite Collection® 2.0 Food Processor FP-12N Series For your safety and continued enjoyment of this product, always read the instruction book carefully before using. RECOMMENDED MAXIMUM WORK BOWL CAPACITIES FOOD CAPACITY CAPACITY 12-CUP WORKBOWL 4-CUP WORKBOWL Sliced or shredded fruit, vegetables or cheese 12 cups N/A Chopped fruit, vegetables or cheese 9 cups 3 cups Puréed fruit, vegetables or cheese 10 cups cooked 3 cups cooked 6 cups puréed 1½ cups puréed Chopped or puréed meat, fish, seafood 2 pounds ½ pound Thin liquid* (e.g. dressing, soups, etc.) 8 cups 3 cups Cake batter One 9-inch cheesecake N/A Two 8-inch homemade layers (1 box 18.5 oz. cake mix) Cookie dough 6 dozen (based on average chocolate N/A chip cookie recipe) White bread dough 5 cups flour N/A Whole wheat bread dough 3 cups flour N/A Nuts for nut butter 5 cups 1½ cups * When processing egg-based liquids, like a custard base for quiche, reduce maximum capacity by 2 cups. 2 counterclockwise to lock it, then remove the IMPORTANT UNPACKING housing base (J) from the bottom of the box. 7. Place the food processor on the countertop INSTRUCTIONS or table. Read the Assembly and Operating This package contains a Cuisinart Elite Instructions (pages 8–10) thoroughly before Collection® 12-Cup Food Processor and the using the machine. accessories for it: 8. Save the shipping cartons and plastic foam 12- and 4-cup work bowls, work bowl cover, blocks. You will find them very useful if you large and small metal chopping/mixing blades, need to repack the processor for moving or dough blade, adjustable slicing disc, reversible other shipment. -

The Beacon, September 12, 2008 Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) Special Collections and University Archives 9-12-2008 The Beacon, September 12, 2008 Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Florida International University, "The Beacon, September 12, 2008" (2008). The Panther Press (formerly The Beacon). 175. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper/175 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Forum for Free Student Expression at Florida International University Vol. 21 Issue 14 www.fi usm.com Septmeber 12, 2008 TUNE IN GIRL POWER HURRICANE FUN HOME OPENER SJMC to produce T.V. show Palin doesn’t spar Obama Surviving the season Student guide to football tickets AT THE BAY PAGE 3 OPINION PAGE 4 LIFE! PAGE 5 SPORTS PAGE 8 FIU FASHION FORWARD UM’s freshmen parking ban will not be imitated EDUARDO MORALES is one of convenience, Staff Writer not supply,” Foster said. “There are always spaces After University of available in the Panther Miami announced this fall Garage, Lot Five and in the that residential freshman overflow area on the north- parking was no longer east side of campus, but allowed, some FIU fresh- these areas are not looked men became worried a at as convenient.” similar plan was coming Other universities, to their University. -

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

John Carpenter Lost Themes II

John Carpenter Lost Themes II track listing: 1 Distant Dream (3:51) 2 White Pulse (4:21) 3 Persia Rising (3:40) 4 Angel’s Asylum (4:17) 5 Hofner Dawn (3:15) 6 Windy Death (3:40) 7 Dark Blues (4:16) 8 Virtual Survivor (3:58) 9 Bela Lugosi (3:23) 10 Last Sunrise (4:29) 11 Utopian Facade (3:48) 12 Real Xeno (4:30) (cD bonus track) key information / selling Points: Hometown / Key Markets: • Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago Selling Points / Key Press: • Lost Themes charted at #44 on Billboard Top Albums • More than 26,000 units of Lost Themes have shipped to date; Soundscan LTD is 14,733 On Halloween 2014, the director and composer John Carpenter introduced • Lost Themes is the highest selling album in label’s history the world to the next phase of his career with “Vortex,” the first single fromLost • Worldwide tour planned – playing live for the first time Themes, his first-ever solo record. In the months that followed,Lost Themes right- ever – with full band and stage production, May-Nov. 2016 fully returned Carpenter to the forefront of the discussion of music and film’s • Primavera, ATP Iceland, and ATP Release the Bats crucial intersection. Carpenter’s foundational primacy and lasting influence on already confirmed genre score work was both rediscovered and reaffirmed. So widespread was the • Secretly Distribution/ADA exclusive Purple & White Swirl acclaim for Lost Themes, that the composer was moved to embark on something Vinyl, edition of 2500 he had never before entertained – playing his music live in front of an audience. -

Dade County Radio December 2012 Playlist

# No Title Artist Length Count 1 Miami Bass FEST III CHICO 1:18 228 2 FreddieMcGregor_Da1Drop 0:07 126 3 dadecountyradio_kendrick DROP 0:05 121 4 DROP 0:20 104 5 daoneradiodrop 0:22 90 6 Black Jesus @thegame 4:52 52 7 In The End (new 2013) @MoneyRod305 ft @LeoBre 3:53 49 8 M.I.A. Feat. @Wale (Dirty) @1Omarion 3:57 48 9 Up (Remix) K Kutta , LoveRance, 50 Cent 2:43 47 10 Drop-DadeCounty Patrice 0:10 47 11 My Hood (Feat Mannie Fresh) B.G. 3:58 46 12 SCOOBY DOO JT MONEY 4:32 45 13 Stay High _Official Music Video_ Fweago Squad (Rob Flamez) Feat Stikkmann 3:58 45 14 They Got Us (Prod. By Big K.R.I.T.) Big K.R.I.T. 3:27 44 15 You Da One Rihanna 3:22 44 16 Love Me Or Not (Radio Version) @MoneyRod305 Ft @Casely 4:04 44 17 Haters Ball Greeezy 3:14 44 18 Playa A** S*** J.T. Money 4:35 44 19 Ni**as In Paris Jay-Z & Kanye West 3:39 43 20 Myself Bad Guy 3:26 43 21 Jook with me (dirty) Ballgreezy 3:46 42 22 Ro_&_Pat_Black_-_Soldier 05_Ridah_Redd_feat._Z 3:37 42 23 Go @JimmyDade 3:49 42 24 Keepa @Fellaonyac 4:43 41 25 Gunplay-Pop Dat Freestyle Gunplay 1:47 41 26 I Need That Nipsey Hussle ft Dom Kennedy 2:47 40 27 Harsh Styles P 4:18 40 28 American Dreamin' Jay-Z 4:48 40 29 Tears Of Joy (Ft. -

O-Week Edition. February 23Rd 2011

O-WEEK EDITION. FEBRUARY 23RD 2011 ? SEND YOUR MAIL TO: letters [email protected] HONI FROM THE VAULT S.R.C. President’s Message to Freshers, March 1946 The first academic year to begin in peace time has as its chief characteristic by far a record number THE of first-year students. Not only is the number exceptionally large, but its composition is also EDITORIAL extraordinary, because of the large number of Heeeeere’s Honi! returned servicemen and women it contains. Welcome (back) to university, and To all who are starting off this year, I wish to welcome to this, the very first edition of Honi extend a very hearty welcome. You have all one Soit* for 2011. thing in common now, namely the membership O-Week) of this University, and this will be the most One of the boys in my year ten English class and recap important feature of your life in the next few once described university as “one long y’all on the years. party,” and to be honest he wasn’t too far considerable goings from the truth. Uni can be an incredibly on around campus and the Your stay at the University will not be fully positive and social environment, but it’s easy to world over the break, just in time worthwhile if you only want to take away your feel overwhelmed and isolated even in the midst for you to drop some knowledge at degree and your knowledge, and not give of thousands of people. To that end, we’ve your first tute. -

Country Airplay; Brooks and Shelton ‘Dive’ In

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JUNE 24, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Thomas Rhett’s Behind-The-Scenes Country Songwriters “Look” Cooks >page 4 Embracing Front-Of-Stage Artist Opportunities Midland’s “Lonely” Shoutout When Brett James sings “I Hold On” on the new Music City Puxico in 2017 and is working on an Elektra album as a member >page 9 Hit-Makers EP Songs & Symphony, there’s a ring of what-ifs of The Highwomen, featuring bandmates Maren Morris, about it. Brandi Carlile and Amanda Shires. Nominated for the Country Music Association’s song of Indeed, among the list of writers who have issued recent the year in 2014, “I Hold On” gets a new treatment in the projects are Liz Rose (“Cry Pretty”), Heather Morgan (“Love Tanya Tucker’s recording with lush orchestration atop its throbbing guitar- Someone”), and Jeff Hyde (“Some of It,” “We Were”), who Street Cred based arrangement. put out Norman >page 10 James sings it with Rockwell World an appropriate in 2018. gospel-/soul-tinged Others who tone. Had a few have enhanced Marty Party breaks happened their careers with In The Hall differently, one a lbu ms i nclude >page 10 could envision an f o r m e r L y r i c alternate world in Street artist Sarah JAMES HUMMON which James, rather HEMBY Buxton ( “ S u n Makin’ Tracks: than co-writer Daze”), who has Riley Green’s Dierks Bentley, was the singer who made “I Hold On” a hit. done some recording with fellow songwriters and musicians Sophomore Single James actually has recorded an entire album that’s expected under the band name Skyline Motel; Lori McKenna (“Humble >page 14 later this year, making him part of a wave of writers who are and Kind”), who counts a series of albums along with her stepping into the spotlight with their own multisong projects. -

J3886 Pan Mac Stocklist Lores.Indd

MACMILLAN CHILDREN’S BOOKS 2021CATALOGUE 2 MACMILLAN CHILDREN’S BOOKS 2021CATALOGUE Illustration from Busy Storytime © Campbell Books 2021 CONTENTS January – June Highlights 4 – 17 Books for Babies and Toddlers 18 Books for Babies 18 CONTENTS Campbell Books 20 Board Books 35 Sound Books and Novelty 43 Picture Books 44 Big Books 60 Under 6 Stand Alone Audio CDs 61 Books and CDs 62 Two Hoots 65 Activity Books 70 Poetry, Plays and Jokes 74 Fiction: 5 + 79 Fiction: 7 + 81 Fiction: 9 + 86 Fiction 11 + 94 Fiction: Teen 96 Young Adult 98 Gift, Classics and Heritage 104 6+ Stand Alone Audio CDs 113 Non-Fiction 114 Kingfi sher 118 Special Interest Titles 131 Accelerated Reading List 140 Index 146 UK Sales 148 Overseas Companies, Agents and Representatives 149 Shortlisted and This edition Also available Also available prize-winning includes an as an audio as an ebook titles audio CD download 2 A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER Welcome to the 2021 by Nicola O’Byrne, are both hilarious picture books Macmillan Children’s to look out for. The Treehouse series has now sold Books illustrated stocklist. 700k through the TCM, bringing laughter to children It is a pleasure to be all across the UK, and we launched a new illustrated looking forward to next series for the same age group this summer: year, and showcasing our InvestiGators by John Patrick Green. This is already list and highlights from becoming a fi rm favourite with younger readers and January to June. All the there is more crazy alligator fun to come next year. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

LH January19 DONE.Indd

JANUARY 2019 Your Community News Source — Serving Sun City Lincoln Hills — ONLINE AT: SUNSENIORNEWS.COM EBRATIN The McCormicks — Running the Retirement Race EL G C BY RUTH MORSE YEARS! Ken and Deanna McCormick are at Deanna’s school in Joy, Illinois, when 17 in their eighties and still have amazing Deanna was a sophomore. Ken was a physical capabilities. When I visited, Ken senior at a rival school in Reynolds, Illinois. had already strung up the outdoor holiday Deanna moved to Iowa after graduation IN THIS ISSUE decorations himself, and the couple was and worked in a bank while Ken joined From the Editors ......................................................3 in the process of upgrading their house, the Air Force. They married in 1956 at the Letter to the Editors ................................................3 including the installation of new fl ooring. Methodist Church in Joy while Ken was But the biggest story was the race stationed in Duluth, Minnesota. He stayed Placer County Supervisor, SCLH Writer .................. 4 that Deanna had just recently completed in the Air Force for twenty-one years until Community Chorus, Players .........................................5 with her daughter and granddaughter. She retirement and that led to a peripatetic Lincoln Veteran Memorial Project.............................. 6 participated in a local four-mile Spartan lifestyle including time in Spain and Iran. Tap, Ballroom, Line Dance .......................................... 7 Race with an obstacle course, and, with the Deanna joined Ken in Duluth, Country Couples, Needle Arts, Painters ................9 support of her family members, was the Ken and Deanna McCormick Minnesota after their wedding. At one Mixed Media, Paper Art ........................................10 oldest person to ever complete the event. -

2015 Annual Report Prague City Tourism CONTENTS

2015 Annual Report Pražská informační služba – Prague City Tourism 2015 Annual Report Arbesovo náměstí 70/4 / Praha 5 / 150 00 / CZ www.prague.eu Prague City Tourism 2015 Annual Report Prague City Tourism CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION BY THE CEO 34 PUBLISHING 6 PROFILE OF THE ORGANIZATION 36 OLD TOWN HALL About Us Organization Chart 38 EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Prague Cultural History Walks 10 MARKETING AND PUBLIC RELATIONS Tour Guide Training and Continuing Education Online Campaign The Everyman's University of Prague Facebook and other Social Media Marketing Themes and Campaigns 40 RESEARCH: PRAGUE VISITORS POLL International Media Relations and Press Trips Domestic Media Relations 44 2015 IN PRAGUE CITY TOURISM FIGURES Partnerships and Collaborations Exhibitions, Trade Shows and Presentations 45 PRAGUE CITY TOURISM FINANCES AND ECONOMIC RESULTS IN 2015 24 VISITOR SERVICES 50 TOURISM IN PRAGUE 2015 Tourist Information Centres Domestic and International Road Shows 56 PRAGUE CITY TOURISM: 2016 OUTLOOK Prague.eu Web Site E-Shop Guide Office INTRODUCTION BY THE CEO From Visions to Results An inseparable part of our overall activities was supporting foreign media, 2015 has been a year of significant professional journalists and bloggers, as well as tour operators and travel agents visiting our advancements for our organization. Its new destination. We provided them with special-interest or general guided tours and corporate name – Prague City Tourism – entered shared insights on new and noteworthy attractions that might be of interest to the public consciousness and began to be used their readers and clients, potential visitors to Prague. by the public at large. A community of travel and tourism experts has voted me Person of the Year, Record numbers of visitors to our capital city also requires significant informational and I was among the finalists of the Manager resources, whether printed (nearly 1,400,000 copies of publications in 13 language of the Year competition.