Back to Futurism: the Ill-Digested Legacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2-2021 The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi Jason Collins The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4143 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SURREALIST VOICE IN MILAN’S ITINERANT POETICS: DELIO TESSA TO FRANCO LOI by JASON M. COLLINS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 i © 2021 JASON M. COLLINS All Rights Reserved ii The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________ ____________Paolo Fasoli___________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _________________ ____________Giancarlo Lombardi_____ Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Paolo Fasoli André Aciman Hermann Haller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins Advisor: Paolo Fasoli Over the course of Italy’s linguistic history, dialect literature has evolved a s a genre unto itself. -

The T Ransrational Poetry of Russian Futurism Gerald J Ara,Tek

The T ransrational Poetry of Russian Futurism E Gerald J ara,tek ' 1996 SAN DIEGO STATE UNIVERSilY PRESS Calexico Mexicali Tijuana San Diego Copyright © 1996 by San Diego State University Press First published in 1996 by San Diego State University Press, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, California 92182-8141 http:/fwww-rohan.sdsu.edu/ dept/ press/ All rights reserved. -', Except for brief passages quoted in a review, no part of thisb ook m b ay e reproduced in an form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography r y , o any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, withoutthe written permission of thecop yright owners. Set in Book Antiqua Design by Harry Polkinhorn, Bill Nericcio and Lorenzo Antonio Nericcio ISBN 1-879691-41-8 Thanks to Christine Taylor for editorial production assistance 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Acknowledgements Research for this book was supported in large part by grants in 1983, 1986, and 1989 from the International Research & Ex changes Board (IREX), with funds provided by the National En dowment for the Humanities, the United States Information Agency, and the US Department of State, which administers the Russian, Eurasian, and East European Research Program (Title VIII). In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to the fol lowing institutions and their staffs for aid essential in complet ing this project: the Fulbright-Bayes Senior Scholar Research Program for further support for the trips in 1983 and 1989, the American Council of Learned Societies for further support for the trip in 1986, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Brit ish Library; iri Moscow: to the Russian State Library, the Rus sian State Archive of Literature and Art, the Gorky Institute of World Literature, the State Literary Museum, and the Mayakovsky Museum; in St. -

Elio Gioanola Carlo Bo Charles Singleton Gianfranco Contini

Elio Gioanola Introduzione Carlo Bo Ricordo di Eugenio Montale Charles Singleton Quelli che restano Gianfranco Contini Lettere di Eugenio Montale Vittorio Sereni Il nostro debito verso Montale Vittore Branca Montale crìtico di teatro Andrea Zanzotto La freccia dei diari Luciano Erba Una forma di felicità, non un oggetto di giudizio Piero Bigongiari Montale tra il continuo e il discontinuo Giovanni Macchia La stanza dell'Amiata Ettore Bonora Un grande trìttico al centro della « Bufera » (La primavera hitleriana, Iride, L'orto) Silvio Guarnieri Con Montale a Firenze http://d-nb.info/945512643 Pier Vincenzo Mengaldo La panchina e i morti (su una versione di Montale) Angelo Jacomuzzi Incontro - Per una costante della poesia montaliana Marco Forti Per « Diario del '71 » Giorgio Bàrberi Squarotti Montale o il superamento del soggetto Silvio Ramat Da Arsenio a Gerti Mario Martelli L'autocitazione nel secondo Montale Rosanna Bettarini Un altro lapillo Glauco Cambon Ancora su « Iride », frammento di Apocalisse Mladen Machiedo Una lettera dì Eugenio Montale (e documenti circostanti) Claudio Scarpati Sullo stilnovismo di Montale Gilberto Lonardi L'altra Madre Luciano Rebay Montale, Clizia e l'America Stefano Agosti Tom beau Maria Antonietta Grignani Occasioni diacroniche nella poesia di Montale Claudio Marabini Montale giornalista Gilberto Finzi Un'intervista del 1964 Franco Croce Satura Edoardo Sanguineti Tombeau di Eusebio Giuseppe Savoca L'ombra viva della bufera Oreste Macrì Sulla poetica di Eugenio Montale attraverso gli scritti critici Laura Barile Primi versi di Eugenio Montale Emerico Giachery La poesia di Montale e il senso dell'Europa Giovanni Bonalumi In margine al « Povero Nestoriano smarrito » Lorenzo Greco Tempo e «fuor del tempo» nell'ultimo Montale . -

Pushkin and the Futurists

1 A Stowaway on the Steamship of Modernity: Pushkin and the Futurists James Rann UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Declaration I, James Rann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Robin Aizlewood, who has been an inspirational discussion partner and an assiduous reader. Any errors in interpretation, argumentation or presentation are, however, my own. Many thanks must also go to numerous people who have read parts of this thesis, in various incarnations, and offered generous and insightful commentary. They include: Julian Graffy, Pamela Davidson, Seth Graham, Andreas Schönle, Alexandra Smith and Mark D. Steinberg. I am grateful to Chris Tapp for his willingness to lead me through certain aspects of Biblical exegesis, and to Robert Chandler and Robin Milner-Gulland for sharing their insights into Khlebnikov’s ‘Odinokii litsedei’ with me. I would also like to thank Julia, for her inspiration, kindness and support, and my parents, for everything. 4 Note on Conventions I have used the Library of Congress system of transliteration throughout, with the exception of the names of tsars and the cities Moscow and St Petersburg. References have been cited in accordance with the latest guidelines of the Modern Humanities Research Association. In the relevant chapters specific works have been referenced within the body of the text. They are as follows: Chapter One—Vladimir Markov, ed., Manifesty i programmy russkikh futuristov; Chapter Two—Velimir Khlebnikov, Sobranie sochinenii v shesti tomakh, ed. -

Cubo-Futurism

Notes Cubo-Futurism Slap in theFace of Public Taste 1 . These two paragraphs are a caustic attack on the Symbolist movement in general, a frequent target of the Futurists, and on two of its representatives in particular: Konstantin Bal'mont (1867-1943), a poetwho enjoyed enormouspopu larityin Russia during thefirst decade of this century, was subsequentlyforgo tten, and died as an emigrein Paris;Valerii Briusov(18 73-1924), poetand scholar,leader of the Symbolist movement, editor of the Salles and literary editor of Russum Thought, who after the Revolution joined the Communist party and worked at Narkompros. 2. Leonid Andreev (1871-1919), a writer of short stories and a playwright, started in a realistic vein following Chekhov and Gorkii; later he displayed an interest in metaphysicsand a leaning toward Symbolism. He is at his bestin a few stories written in a realistic manner; his Symbolist works are pretentious and unconvincing. The use of the plural here implies that, in the Futurists' eyes, Andreev is just one of the numerousepigones. 3. Several disparate poets and prose writers are randomly assembled here, which stresses the radical positionof the signatories ofthis manifesto, who reject indiscriminately aU the literaturewritt en before them. The useof the plural, as in the previous paragraphs, is demeaning. Maksim Gorkii (pseud. of Aleksei Pesh kov, 1�1936), Aleksandr Kuprin (1870-1938), and Ivan Bunin (1870-1953) are writers of realist orientation, although there are substantial differences in their philosophical outlook, realistic style, and literary value. Bunin was the first Rus sianwriter to wina NobelPrize, in 1933.AJeksandr Biok (1880-1921)is possiblythe best, and certainlythe most popular, Symbolist poet. -

The Poet Takes Himself Apart on Stage: Vladimir Mayakovsky's

The Poet Takes Himself Apart on Stage: Vladimir Mayakovsky’s Poetic Personae in Vladimir Mayakovsky: Tragediia and Misteriia-buff By Jasmine Trinks Senior Honors Thesis Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill March 2015 Approved: ____________________________ Kevin Reese, Thesis Advisor Radislav Lapushin, Reader CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………1 CHAPTER I: Mayakovsky’s Superfluous Sacrifice: The Poetic Persona in Vladimir Mayakovsky: Tragediia………………….....4 CHAPTER II: The Poet-Prophet Confronts the Collective: The Poetic Persona in Two Versions of Misteriia-buff………………25 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………47 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………50 ii INTRODUCTION In his biography of Vladimir Mayakovsky, Edward J. Brown describes the poet’s body of work as a “regular alternation of lyric with political or historical themes,” noting that Mayakovsky’s long lyric poems, like Человек [Man, 1916] and Про это [About That, 1923] are followed by the propagandistic Мистерия-буфф [Mystery-Bouffe, 1918] and Владимир Ильич Ленин [Vladimir Il’ich Lenin, 1924], respectively (Brown 109). While Brown’s assessment of Mayakovsky’s work is correct in general, it does not allow for adequate consideration of the development of his poetic persona over the course of his career, which is difficult to pinpoint, due in part to the complex interplay of the lyrical and historical in his poetry. In order to investigate the problem of Mayakovsky’s ever-changing and contradictory poetic persona, I have chosen to examine two of his plays: Владимир Маяковский: Трагедия [Vladimir Mayakovsky: A Tragedy, 1913] and both the 1918 and 1921 versions of Mystery- Bouffe. My decision to focus on Mayakovsky's plays arose from my desire to examine what I termed the “spectacle-ization” of the poet’s ego—that is, the representation of the poetic persona in a physical form alive and on stage. -

Constructivist Book Design: Shaping the Proletarian Conscience

Constructivist Book Design: Shaping the Proletarian Conscience We . are satisfied if in our book the lyric and epic Futurist books were unconventionally small, and whether Margit Rowell evolution of our times is given shape. —El Lissitzky1 or not they were made by hand, they deliberately empha- sized a handmade quality. The pages are unevenly cut One of the revelations of this exhibition and its catalogue and assembled. The typed, rubber- or potato-stamped is that the art of the avant-garde book in Russia, in the printing or else the hectographic, or carbon-copied, early decades of this century, was unlike that found any- manuscript letters and ciphers are crude and topsy-turvy where else in the world. Another observation, no less sur- on the page. The figurative illustrations, usually litho- prising, is that the book as it was conceived and pro- graphed in black and white, sometimes hand-colored, duced in the period 1910–19 (in essentially what is show the folk primitivism (in both image and technique) known as the Futurist period) is radically different from of the early lubok, or popular woodblock print, as well as its conception and production in the 1920s, during the other archaic sources,3 and are integrated into and inte- decade of Soviet Constructivism. These books represent gral to, as opposed to separate from, the pages of poetic two political and cultural moments as distinct from one verse. The cheap paper (sometimes wallpaper), collaged another as any in the history of modern Europe. The covers, and stapled spines reinforce the sense of a hand- turning point is of course the years immediately follow- crafted book. -

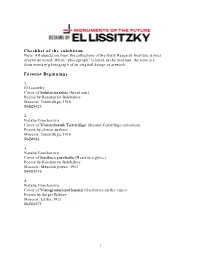

Checklist of the Exhibition Checklist of the Exhibition Note: All Objects Are

Checklist of the exhibition Note: All objects are from the collections of the Getty Research Institute, unless otherwise noted. When “photograph” is listed as the medium, the item is a documentary photograph of an original design or artwork. Futurist Beginnings 1. El Lissitzky Cover of Solntse na izlete (Spent sun) Poems by Konstantin Bolshakov Moscow: Tsentrifuga, 1916 88-B24323 2. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Vtoroi sbornik Tsentrifugi (Second Centrifuge collection) Poems by eleven authors Moscow: Tsentrifuga, 1916 90-B4642 3. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Serdtse v perchatke (Heart in a glove) Poems by Konstantin Bolshakov Moscow: Mezonin poezii, 1913 88-B24316 4. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Vetrogradari nad lozami (Gardeners on the vines) Poems by Sergei Bobrov Moscow: Lirika, 1913 88-B24275 1 4a. Natalia Goncharova Pages from Vetrogradari nad lozami (Gardeners on the vines) Poems by Sergei Bobrov Moscow: Lirika, 1913 88-B24275 Yiddish Book Design 5. El Lissitzky Dust jacket from Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 6a. El Lissitzky Cover of Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 6b. El Lissitzky Page from Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 7. El Lissitzky Cover of Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An everyday conversation: A story) Tale by Moses Broderson Moscow: Ferlag Chaver, 1917 93-B15342 8. El Lissitzky Frontispiece from deluxe edition of Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An everyday conversation: A story) Tale by Moses Broderson Moscow: Shamir, 1917 93-B15342 2 9. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fillia's Futurism Writing

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian By Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 © Copyright by Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War By Adriana Marie Baranello Doctor of Philosophy in Italian University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Lucia Re, Co-Chair Professor Claudio Fogu, Co-Chair Fillia (Luigi Colombo, 1904-1936) is one of the most significant and intriguing protagonists of the Italian futurist avant-garde in the period between the two World Wars, though his body of work has yet to be considered in any depth. My dissertation uses a variety of critical methods (socio-political, historical, philological, narratological and feminist), along with the stylistic analysis and close reading of individual works, to study and assess the importance of Fillia’s literature, theater, art, political activism, and beyond. Far from being derivative and reactionary in form and content, as interwar futurism has often been characterized, Fillia’s works deploy subtler, but no less innovative forms of experimentation. For most of his brief but highly productive life, Fillia lived and worked in Turin, where in the early 1920s he came into contact with Antonio Gramsci and his factory councils. This led to a period of extreme left-wing communist-futurism. In the mid-1920s, following Marinetti’s lead, Fillia moved toward accommodation with the fascist regime. This shift to the right eventually even led to a phase ii dominated by Catholic mysticism, from which emerged his idiosyncratic and highly original futurist sacred art. -

11 Lanfranco Binni, La Protesta Di Walter Binni. Una Biografia 13 Premessa 15 1 • Un Inizio Autobiografico

INDICE 11 Lanfranco Binni, La protesta di Walter Binni. Una biografia 13 Premessa 15 1 • Un inizio autobiografico. Schegge di ricordi 37 2. «Ilporto è la furia del mare». L'incontro con Aldo Capitini 39 3. Binni normalista: ritratto del critico da giovane 45 4. La cospirazione antifascista e il liberalsocialismo 50 5- La Resistenza 53 6. Liberalsocialisti e liberalproprietari. Binni socialista 61 7. All'Assemblea costituente 67 8. A Genova 71 9. Binni all'Università di Firenze, «socialista senza tessera» 74 10. L'adesione al Psi e Li battaglia per la democratizzazione dell'università 80 11. Costume e cultura: una polemica 84 12. A Roma 87 13. L'assassinio di Paolo Rossi 95 14. // Sessantotto a Roma 100 15. La nuova sinistra e gli anni settanta 110 16.// riflusso degli anni ottanta 116 17'. //pensiero dominante \TJ 18. Millenovecentonovantasette 135 19. Quasi un racconto 143 Tracce per una biografia. Lettere a Walter Binni (1931-1997) 145 Premessa 147 1. Aldo Capitini, 12 agosto 1931 149 2. Gaetano Chiavacci, 18 settembre 1931 150 3. Aldo Capitini, 6 novembre 1931 151 4. Attilio Momigliano, 17 novembre 1934 151 5. Giorgio Pasquali, 10 agosto 1935 154 6. Luigi Russo, 4 ottobre 1935 156 7. Luigi Russo, 29 febbraio 1936 156 8. Eugenio Montale, 6 novembre 1936 157 9. Luigi Russo, 9 novembre 1939 158 10. Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, 3 dicembre 1939 159 11. Giuseppe Dessi, 26 marzo 1940 160 12. Arrigo Benedetti, 3 aprile 1940 161 13. Pietro Pancrazi, 3 luglio 1940 162 14. Luigi Russo, 10 luglio 1940 163 15. Luigi Russo, 24 agosto 1940 163 16. -

Poetry and the Visual in 1950S and 1960S Italian Experimental Writers

The Photographic Eye: Poetry and the Visual in 1950s and 1960s Italian Experimental Writers Elena Carletti Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. I acknowledge that this thesis has been read and proofread by Dr. Nina Seja. I acknowledge that parts of the analysis on Amelia Rosselli, contained in Chapter Four, have been used in the following publication: Carletti, Elena. “Photography and ‘Spazi metrici.’” In Deconstructing the Model in 20th and 20st-Century Italian Experimental Writings, edited by Beppe Cavatorta and Federica Santini, 82– 101. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019. Abstract This PhD thesis argues that, in the 1950s and 1960s, several Italian experimental writers developed photographic and cinematic modes of writing with the aim to innovate poetic form and content. By adopting an interdisciplinary framework, which intersects literary studies with visual and intermedial studies, this thesis analyses the works of Antonio Porta, Amelia Rosselli, and Edoardo Sanguineti. These authors were particularly sensitive to photographic and cinematic media, which inspired their poetics. Antonio Porta’s poetry, for instance, develops in dialogue with the photographic culture of the time, and makes references to the photographs of crime news. -

Art and Technology Between the Usa and the Ussr, 1926 to 1933

THE AMERIKA MACHINE: ART AND TECHNOLOGY BETWEEN THE USA AND THE USSR, 1926 TO 1933. BARNABY EMMETT HARAN PHD THESIS 2008 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDREW HEMINGWAY UMI Number: U591491 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591491 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Bamaby Emmett Haran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the meeting of art and technology in the cultural arena of the American avant-garde during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It assesses the impact of Russian technological Modernism, especially Constructivism, in the United States, chiefly in New York where it was disseminated, mimicked, and redefined. It is based on the paradox that Americans travelling to Europe and Russia on cultural pilgrimages to escape America were greeted with ‘Amerikanismus’ and ‘Amerikanizm’, where America represented the vanguard of technological modernity.