Poetry--Part One," a Way of Saying," Part Two," Search

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Interscholastic League Literary Criticism Contest • Invitational a • 2021

University Interscholastic League Literary Criticism Contest • Invitational A • 2021 Part 1: Knowledge of Literary Terms and of Literary History 30 items (1 point each) 1. A line of verse consisting of five feet that char- 6. The repetition of initial consonant sounds or any acterizes serious English language verse since vowel sounds in successive or closely associated Chaucer's time is known as syllables is recognized as A) hexameter. A) alliteration. B) pentameter. B) assonance. C) pentastich. C) consonance. D) tetralogy. D) resonance. E) tetrameter. E) sigmatism. 2. The trope, one of Kenneth Burke's four master 7. In Greek mythology, not among the nine daugh- tropes, in which a part signifies the whole or the ters of Mnemosyne and Zeus, known collectively whole signifies the part is called as the Muses, is A) chiasmus. A) Calliope. B) hyperbole. B) Erato. C) litotes. C) Polyhymnia. D) synecdoche. D) Urania. E) zeugma. E) Zoe. 3. Considered by some to be the most important Irish 8. A chronicle, usually autobiographical, presenting poet since William Butler Yeats, the poet and cele- the life story of a rascal of low degree engaged brated translator of the Old English folk epic Beo- in menial tasks and making his living more wulf who was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize for through his wit than his industry, and tending to Literature is be episodic and structureless, is known as a (n) A) Samuel Beckett. A) epistolary novel. B) Seamus Heaney. B) novel of character. C) C. S. Lewis. C) novel of manners. D) Spike Milligan. D) novel of the soil. -

Poetry Vocabulary

Poetry Vocabulary Alliteration: Definition: •The repetition of consonant sounds in words that are close together. •Example: •Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. How many pickled peppers did Peter Piper pick? Assonance: Definition: •The repetition of vowel sounds in words that are close together. •Example: •And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side Of my darling, my darling, my life and my bride. -Edgar Allen Poe, from “Annabel Lee” Ballad: Definition: •A song or songlike poem that tells a story. •Examples: •“The Dying Cowboy” • “The Cremation of Sam McGee” Cinquain: Definition: • A five-line poem in which each line follows a rule. 1. A word for the subject of the poem. 2. Two words that describe it. 3. Three words that show action. 4. Four words that show feeling. 5. The subject word again-or another word for it. End rhyme: Definition: • Rhymes at the ends of lines. • Example: – “I have to speak-I must-I should -I ought… I’d tell you how I love you if I thought The world would end tomorrow afternoon. But short of that…well, it might be too soon.” The end rhymes are ought, thought and afternoon, soon. Epic: Definition: • A long narrative poem that is written in heightened language and tells stories of the deeds of a heroic character who embodies that values of a society. • Example: – “Casey at the Bat” – “Beowulf” Figurative language: Definition: • An expressive use of language. • Example: – Simile – Metaphor Form: Definition: • The structure and organization of a poem. Free verse: Definition: • Poetry without a regular meter or rhyme scheme. -

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

Gcse English Literature (8702)

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE (8702) Past and present: poetry anthology For exams from 2017 Version 1.0 June 2015 AQA_EngLit_GCSE_v08.indd 1 31/07/2015 22:14 AQA GCSE English Literature Past and present: poetry anthology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing on any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of the licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Notice to teachers: It is illegal to reproduce any part of this work in material form (including photocopying and electronic storage) except under the following circumstances: i) where you are abiding by a licence granted to your school or institution by the Copyright Licensing Agency; ii) where no such licence exists, or where you wish to exceed the terms of a licence, and you have gained the written permission of The Publishers Licensing Society; iii) where you are allowed to reproduce without permission under the provisions of Chapter 3 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Photo permissions 5 kieferpix / Getty Images, 6 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 8 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 9 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 11 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 12 Photos.com/Thinkstock, 13 Stuart Clarke/REX, 16 culture-images/Lebrecht, 16,© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 17 Topfoto.co.uk, 18 Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

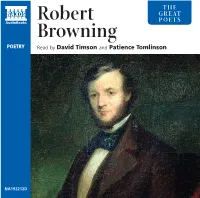

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

"A Brief Companion to Selected Poems from Jehanne Dubrow's

A BRIEF COMPANION TO SELECTED POEMS FROM JEHANNE DUBROW’S STATESIDE Associate Professor Temple Cone, USNA English Department Overview Jehanne Dubrow’s third book of poems, Stateside, is concerned with the difficulties that military families, particularly spouses, encounter throughout deployment. Dubrow, herself the wife of a Naval officer, balances images drawn quotidian experience in America with intricately formal verse that uses dramatic personae and alludes extensively to Western war literature, particularly Homer’s Odyssey. The book addresses experiences far more likely to touch far more of our midshipmen’s lives than combat: the difficult psychological adjustments and challenges to marital and family harmony that military deployment poses. Yet these experiences may prove difficult to discuss in the classroom. They challenge midshipmen to imagine a future they themselves have not yet lived, and they challenge instructors to address the messy, unglamorous aspects of military life, some of which may touch uncomfortably close to home; as Dubrow notes, “it’s hard to know: / the farther out a vessel drifts, / will contents stay in place, or shift?” (“Secure for Sea”). But if midshipmen and faculty can learn to focus on and consider the poetic elements of these poems, they may find an effective and amenable way of engaging with such difficult subjects. Certainly Dubrow has faith in poetry as a mode of expression; after all, she has chosen to write poems about a war primarily represented, so far, in memoir and film. Dubrow’s Stateside offers midshipmen and faculty a chance to engage with unpleasant but professionally relevant subjects, and perhaps to discover how poetry can articulate and even clarify the complexities of human experience. -

ED 105 498 CS 202 027 Introduction to Poetry. Language Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 105 498 CS 202 027 TITLE Introduction to Poetry. Language Arts Mini-Course. INSTITUTION Lampeter-Strasburg School District, Pa. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 13p.; See related documents CS202024-35; Product of Lampeter-Strasburg High School EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Course Descriptions; Course Objectives; *Curriculum Guides; Instructional Materials; *Language Arts; Literature; *Poetry; Secondary Education; *Short Courses IDENTIFIERS Minicourses ABSTRACT This language arts minicourse guide for Lampeter-Strasburg (Pennsylvania) High School contains a topical outline of an introduction to a poetry course. The guide includes a list of twenty course objectives; an outline of the definitions, the stanza forms, and the figures of speech used in poetry; a description of the course content .nd concepts to be studied; a presentation of activities and procedures for the classroom; and suggestions for instructional materials, including movies, records, audiovisual aids, filmstrips, transparencies, and pamphlets and books. (RB) U S Oh PAR TmENT OF HEALTH C EOUCATKIN WELFARE NAT.ONA, INSTITUTE OF EOUCATION Ch DO. Ls. 1 N THA) BE E 4 REPRO ^,,)I qAt L'e AS RECEIVED FROM 1' HI PE 4 sON OR ulICHLNIZA T ION ORIGIN :.' 4L, , T PO,N' s OF .IIE K OR OP .NICINS LiN .." E D DO NOT riFcE SSARL + RE PRE ,E % , Lr lat_ 4.% 00NAL INS T TUT e OF CD c D , .'`N POs. T 1C14 OR POLICY uJ Language Arts Mini-Course INTRODUCTION TO POETRY Lampeter-Strasburg High School ERM.SSION TO RE POODuCETHIS COPY M. 'ED MATERIAL HA; BEEN GRANTED BY Lampeter, Pennsylvania Lampeter-Strasburg High School TD ERIC AV) ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING P.t,EP AGREEMENTS .SiTH THE NATIONAL IN STTuTE Or EDUCATION FURTHER 1973 REPRO PUCTION OU'SIDE THE EPIC SYSTEMRE QUIRES PERMISS'ON OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER N O INTRODUCTION TO POETRY OBJECTIVES: 1. -

My Last Duchess Porphyria's Lover Robert Browning 1812–1889

The Influence of Romanticism My Last Duchess RL 1 Cite strong and thorough Porphyria’s Lover textual evidence to support inferences drawn from the Poetry by Robert Browning text. RL 5 Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts KEYWORD: HML12-944A of a text contribute to its overall VIDEO TRAILER structure and meaning as well as its aesthetic impact. RL 10 Read and comprehend literature, Meet the Author including poems. SL 1 Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions. Robert Browning 1812–1889 “A minute’s success,” remarked the poet character in an emotionally charged situation. Robert Browning, “pays for the failure of While critics attacked his early dramatic years.” Browning spoke from experience: poems, finding them difficult to understand, did you know? for years, critics either ignored or belittled Browning did not allow the reviews to keep his poetry. Then, when he was nearly 60, him from continuing to develop this form. Robert Browning . he became an object of near-worship. • became an ardent Secret Love In 1845, Browning met the admirer of Percy Bysshe Precocious Child An exceptionally bright poet Elizabeth Barrett and began a famous Shelley at age 12. child, Browning learned to read and write romance that has been memorialized in both • achieved fluency in by the time he was 5 and composed his film and literature. Against the wishes of Latin, Greek, Italian, and first, unpublished volume of poetry at Barrett’s overbearing father, the two poets French by age 14. 12. At the age of 21 he published his first married in secret in 1846 and eloped to • wrote the children’s book, Pauline (1833), to negative reviews. -

Introduction to Poetry Lecture Notes Professor Merrill Cole

Introduction to Poetry Lecture Notes Professor Merrill Cole The Basics of How to Read a Poem No good poem offers to any reader all that it has on the first reading. Poetry tends to be far denser than prose, requiring concentration on every word, every line, every rhyme, every metaphor, every sound, every image, every punctuation mark. It all matters. Poetry is not throw-away writing, like you might find in a newspaper, to be read quickly and pushed aside. The poet, Ezra Pound, said that “Literature is the news that stays news.” Good poems have something more to say on the second, fifth, or fiftieth reading. There is no easy formula you can apply to read a poem. Interpretation is not a hard science, but something more like an art. Poetry reading, like violin playing, requires practice, so the more poems you study, and the more you write about them, the better reader and writer you will become. However, there are strategies that you can use from the very beginning that can assist your understanding and make reading unfamiliar poems more fun. I would suggest that when reading a poem for the first time, don’t worry about discovering the overall meaning, but just register your initial impressions. On the second reading—there always needs to be a second reading—determine the exact sense of every word. If you don’t know or aren’t sure about a word, look it up in the dictionary. Whenever possible, it’s better to read a poem aloud, for you will hear things you did not see on the page. -

Marling Hall (1942)

MARLING HALL (1942) Hilary Temple 5 Dean Swift (Jonathan Swift): ‘I shall be like that tree, I shall die at the top.’ Works of Swift ed. W. Scott 1814 vol 1 p.443 Actaeon: hunter in Greek myth who accidentally saw Artemis bathing, was turned into a stag and killed by her hounds+MB 236, AF 200 There is here and there a grayling but mostly there isn’t: ‘I wind about, and in and out,/With here and there a blossom sailing,/And here and there a lusty trout,/And here and there a grayling.’ Tennyson, The Brook 6 One letter changed in Nutfield: Lord Nuffield, manufacturer of the first mass-market British car, the Morris. +CC106 dog watch: the two short watches of the 24 hours, 16.00-18.00 and 18.00-20.00. Also p. 170 9 One that has had losses: Is this a quotation? 13 Teaching is no inheritance: ‘Service is No Inheritance, Or Rules to Servants’. Jonathan Swift – subtitled ‘To be read constantly one night every week upon going to bed’. Various versions by AT include Reading law … SH48; poor relations PE378; Red Cross LAR98; service LAR278; a fellowship HaR 190; teaching 196; service NTL286. 15 Pook’s Piece an allusion to Kipling’s [Puck of] Pook’s Hill? Appears as Pooker’s in Wild Strawberries 16 Bench, ie in court as a magistrate – a US edition misprinted this as Beach 19 race : more usually ‘racé’ or ‘de race’, meaning thoroughbred. 24 A Bean-Stripe; also Apple Eating: real poem by Robert Browning, 1883, as obscure as its title! 27 Valoroso – King Valoroso is from Thackeray’s The Rose and the Ring two little girls – the Leslies only had boys. -

English 11 Poetic Terms

English 11 Poetic Terms Apostrophe An apostrophe is an exclamatory rhetorical figure of speech, when a talker or writer breaks off and directs speech to an imaginary person or abstract quality or idea. In dramatic works and poetry written in or translated into English, such a figure of speech is often introduced by the exclamation "O.” Example. "Where, O death, thy sting? where, O death, thy victory?"(1 Corinthians 15:55) Assonance Assonance is repetition of vowel sounds to create internal rhyming within phrases or sentences. Example. In the phrase, "Do you like blue?" the /u/ ("o"/"ou"/"ue" sound) is repeated within the sentence and is assonant. Consonance Consonance is a stylistic device, most commonly used in poetry and songs, characterized by the repetition of the same consonant two or more times in short succession. Example. Pitter patter. All mammals named Sam are clammy. Dissonance Dissonance is the deliberate avoidance of assonance, and, in poetry, is similar to cacophony. Example. “'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe.” -Lewis Carroll‟s “Jabberwocky” Repetition Repetition is the simple repeating of a word, within a sentence or a poetical line, with no particular placement of the words, in order to emphasize. This is such a common literary device that it is almost never even noted as a figure of speech. Example. “Today, as never before, the fates of men are so intimately linked to one another that a disaster for one is a disaster for everybody.”(Natalia Ginzburg, The Little Virtues, 1962) direge me in veritate tua -1- Saint Thomas Aquinas High School English 11 Poetic Terms Meter In poetry, the meter (or metre) is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse. -

Notes on Prosody

Notes on Middle English Prosody Dr. A Mitchell Sound and Sense Middle English poets typically delight in the accidental harmonies and disharmonies of verbal sounds. Sometimes sound is deliberately made to echoe sense, but more often accoustic patterns do not serve a referential or mimetic function. Syncopated rhythm may just be pleasurable to hear in the voice; variation may aid expressiveness or enhance interest; or sounds may be affective or mnemonic. Sound patterns also function as a sign of the poet’s pedigree, affiliations, or tastes. But in any event critics can probably make only modest claims about the significance of acoustic effects in the vernacular – some measure of irregularity is just a natural consequence of writing in Middle English. Rhyme is the most familiar sound pattern, and it basically demands that the poetic composition be oriented around the music (not the other way around). As a result, the semantic may be subordinated to the sonic or phonetic: e.g., syntax is inverted or contorted so as to get the proper rhyme in place; rhyme words are chosen less for sense than for sound. But of course rhymes may also produce interesting semantic juxtapositions or recapitulations, and occasionally Chaucer among others uses rhyme deftly to produce harmony and discordance, parallelism and antithesis. The main types of rhyme are the following. • end rhyme (most common) • internal rhyme (within a line) • masculine (single-sllable, or when final stressed syllable rhymes as in cat/hat) • feminine (rhymed stressed syllable followed by unstressed as in butter/clutter) • exact rhyme and rime riche (on the same sounds) • near rhyme (not a failed rhyme, it has the salutary effect of avoiding monotony) You will recognize these additional sound effects: • onomatapoia • assonance • alliteration • consonance Metrics: Alliterative and Accentual-Syllabic Some Medieval English verse is alliterative (that of Langland and the so-called poems of the Alliterative Revival), but much is what we call accentual-syllabic.