A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

19 bus time schedule & line map 19 Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre View In Website Mode The 19 bus line (Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 8:45 AM (2) Rotherham Town Centre <-> Thurcroft: 8:50 AM - 4:20 PM (3) Rotherham Town Centre <-> Worksop: 6:00 AM - 7:20 PM (4) Thurcroft <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 9:18 AM - 4:48 PM (5) Worksop <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 5:20 AM - 5:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 19 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 19 bus arriving. Direction: Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre 19 bus Time Schedule 47 stops Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday Not Operational Dinnington Interchange/A2, Dinnington Monday Not Operational Constable Lane, Anston Tuesday 8:45 AM Breck Lane/Outgang Lane, Dinnington Wednesday 8:45 AM Breck Lane/Anne Street, Throapham Thursday 8:45 AM St Johns Road/Kingswood Avenue, Laughton-En- Friday 8:45 AM Le-Morthen Saturday 8:45 AM St Johns Road/St Johns Court, Laughton-En-Le- Morthen School Road/High Street, Laughton-En-Le- Morthen 19 bus Info Direction: Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre School Road/Castle Green, Laughton-En-Le- Stops: 47 Morthen Trip Duration: 45 min Line Summary: Dinnington Interchange/A2, Hangsman Lane/Glaisdale Close, Laughton Dinnington, Breck Lane/Outgang Lane, Dinnington, Common Breck Lane/Anne Street, Throapham, St Johns Road/Kingswood Avenue, Laughton-En-Le-Morthen, 7 Hangsman Lane, Thurcroft -

Moorthorpe Primary School, Pontefract, West Yorkshire

Determination Case reference: VAR2109 Admission authority: Wakefield Metropolitan District Council for Moorthorpe Primary School, Pontefract, West Yorkshire Date of decision: 31 March 2021 Determination In accordance with section 88E of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998, I approve the proposed variation to the admission arrangements determined by Wakefield Metropolitan District Council for Moorthorpe Primary School, Pontefract for September 2021. I determine that for September 2021 the Published Admission Number shall be reduced from 45 to 30. The referral 1. Wakefield Metropolitan District Council (the local authority) has referred a proposal for a variation to the admission arrangements for September 2021 for Moorthorpe Primary School, Pontefract (the school), to the Office of the Schools Adjudicator. The school is a community school for children aged three to eleven in Pontefract. 2. The proposed variation is that the published admission number (PAN) for the school be reduced from 45 to 30 for September 2021. Jurisdiction 3. The referral was made to me in accordance with section 88E of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998 (the Act) which states that: “where an admission authority (a) have in accordance with section 88C determined the admission arrangements which are to apply for a particular school year, but (b) at any time before the end of that year consider that the arrangements should be varied in view of a major change in circumstances occurring since they were so determined, the authority must [except in a case where the authority’s proposed variations fall within any description of variations prescribed for the purposes of this section] (a) refer their proposed variations to the adjudicator, and (b) notify the appropriate bodies of the proposed variations”. -

Consultation Statement

1 Introduction The Neighbourhood Plan steering group has been committed in undertaking consistent, transparent, effective and inclusive periods of community consultation throughout the development of the Neighbourhood Plan (NP) and associated evidence base. The Neighbourhood Plan Regulations require that, when a Neighbourhood Development Plan is submitted for examination, a statement should also be submitted setting out details of those consulted, how they were consulted, the main issues and concerns raised and how these have been considered and, where relevant, addressed in the proposed Plan. Legal Basis: Section 15(2) of part 5 of the Neighbourhood Planning Regulations (as amended) 2012 sets out that, a consultation statement should be a document containing the following: • Details of the persons and bodies who were consulted about the proposed Neighbourhood Development Plan; • Explanation of how they were consulted; • Summary of the main issues and concerns raised by the persons consulted; and • Description of how these issues and concerns have been considered and, where relevant, addressed in the proposed NP. The NP for Hodsock/ Langold will cover the period 2019 until 2037. The NP proposal does not deal with county matters (mineral extraction and waste development), nationally significant infrastructure or any other matters set out in Section 61K of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. Our Consultation Statement This statement outlines the stages in which have led to the production of the Hodsock/Langold NP in terms of consultation with residents, businesses in the parish, stakeholders and statutory consultees. In addition, this statement will provide a summary and, in some cases, detailed descriptions of the numerous consultation events and other ways in which residents and stakeholders were able to influence the content of the Plan. -

Equality and Diversity Strategy 2021

Equality and Diversity Strategy 2021 - 2025 2 www.bassetlaw.gov.uk Contents 4 | 1. Foreword 5 | 2. Our Equality Duties 6 | 3. Our Objectives 2020-2024 9 | 4. Our Workforce 12 | Appendix – Bassetlaw Demographic Profile 01909 533 533 3 1. Foreword As a Council, we have a duty to produce a Single Equality Scheme and this Strategy forms our next Scheme for 2021-2025, guiding our approach to increasing opportunities across the District and improving access to Council services. Bassetlaw District Council’s Equality & Diversity Strategy 2021-2025 builds on the foundations of our previous strategy to ensure that equality is further embedded into our policies, procedures and every- day working, and that we embrace diversity and recognise that everyone has their own unique needs, characteristics, skills, and abilities. The year 2020 was an exceptionally challenging year for all of us. The Covid-19 pandemic meant that the Council needed to provide extra support to the most vulnerable in society and find new ways to deliver its services. The next four years will be a critical period for the Council and its partners in ensuring Bassetlaw’s economy can bounce back from the impacts of Covid-19 and Brexit, and that residents and businesses can continue to be supported effectively. The Strategy is the next step in a journey to better understand our communities and anticipate the needs of residents and service users. The Strategy identifies five key objectives for the next four years, and the actions we will take to deliver each of these. The objectives have been identified through our ongoing conversations with residents, and analysing the latest data both internally and externally. -

Applications and Decisions for the North East of England

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 6338 PUBLICATION DATE: 10/04/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 01/05/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 17/04/2019 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners Copies of Applications and Decisions can be inspected -

South Kirkby & Moorthorpe Town Council Newsletter

Autumn/Winter Edition 2015 South Kirkby & Moorthorpe Town Council Newsletter at the Theatre Royal, Win 2 tickets to the Dick Wakefield on 2 January 2016. Whittington pantomime See Page 6 for full details WELCOME to this edition of the Community Voice brought to you by South Kirkby and Moorthorpe Town Council. Delivery of the Newsletter has been funded by advertising and all future editions will be paid for by sponsorship and advertising. With cuts to local services from central government we will aim to provide the One Stop Shop residents of South Kirkby and Moorthorpe with a range of services that otherwise we are starting will be the provision of free Moorthorpe would not be available to you. For instance wifi at Moorthorpe Railway Station - if it our One Stop Shop is now up and running is a success we will roll it out across the Railway Station at Moorthorpe Station, where people can community. The Town Council are proud to obtain free advice on a range of issues. We hope you enjoy this newsletter. Please announce the launch of the free We are organising events at the Grove Hall feel free to contact us about anything either by calling 01977 642159 or by e mail advice services at Moorthorpe Railway and our first one A Christmas Concert was at . Station making the station a “one stop fully booked within 3 days. Residents will be [email protected] Alternatively come and see us you are more shop” for general wellbeing advice and kept informed about forthcoming events. Meanwhile we have adapted an old than welcome.. -

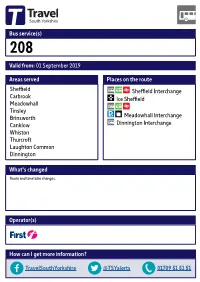

Valid From: 01 September 2019 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas

Bus service(s) 208 Valid from: 01 September 2019 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Carbrook Ice Sheffield Meadowhall Tinsley Brinsworth Meadowhall Interchange Canklow Dinnington Interchange Whiston Thurcroft Laughton Common Dinnington What’s changed Route and timetable changes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 208 01/02/2019 Scholes Parkgate Dalton Thrybergh Braithwell Ecclesfield Ravenfield Common Kimberworth East Dene Blackburn ! Holmes Meadowhall, Interchange Flanderwell Brinsworth, Hellaby Bonet Lane/ Bramley Wincobank Brinsworth Lane Maltby ! Longley ! Brinsworth, Meadowhall, Whiston, Worrygoose Lane/Reresby Drive ! Ñ Whitehill Lane/ Meadowhall Drive/ Hooton Levitt Bawtry Road Meadowhall Way 208 Norwood ! Thurcroft, Morthen Road/Green Lane Meadowhall, Whiston, ! Meadowhall Way/ Worrygoose Lane/ Atterclie, Vulcan Road Greystones Road Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Green Arbour Road ! Pitsmoor Atterclie Road/ Brinsworth, Staniforth Road Comprehensive School Bus Park ! Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Peter Street Laughton Common, ! ! Station Road/Hangsman Lane ! Atterclie, AtterclieDarnall Road/Shortridge Street ! ! ! Treeton Dinnington, ! ! ! Ulley ! Doe Quarry Lane/ ! ! ! Dinnington Comp School ! Sheeld, Interchange Laughton Common, Station Road/ ! 208! Rotherham Road 208 ! Aughton ! Handsworth ! 208 !! Manor !! Dinnington, Interchange Richmond ! ! ! Aston database right 2019 Swallownest and Heeley Todwick ! Woodhouse yright p o c Intake North Anston own r C Hurlfield ! data © y Frecheville e Beighton v Sur e South Anston c ! Wales dnan ! r O ! ! ! ! Kiveton Park ! ! ! ! ! ! Sothall ontains C 2019 ! = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop 24 hour clock 24 hour clock Throughout South Yorkshire our timetables use the 24 hour clock to avoid confusion between am and pm times. -

Policing-Policy-During-Strike-Report

' The Police Committee Special Sub-Committee at their meeting on 24 January 19.85 approved this report and recommended that it should be presented to the Police Committee for their approval. In doing so, they wish to place on record their appreciation and gratitude to all the members of the County Council's Department of Administration who have assisted and advised the Sub-Committee in their inquiry or who have been involved in the preparation of this report, in particular Anne Conaty (Assistant Solicitor), Len Cooksey (Committee Administrator), Elizabeth Griffiths (Secretary to the Deputy County Clerk) and David Hainsworth (Deputy County Clerk). (Councillor Dawson reserved his position on the report and the Sub-Committee agreed to consider a minority report from him). ----------------------- ~~- -1- • Frontispiece "There were many lessons to be learned from the steel strike and from the Police point of view the most valuable lesson was that to be derived from maintaining traditional Police methods of being firm but fair and resorting to minimum force by way of bodily contact and avoiding the use of weapons. My feelings on Police strategy in industrial disputes and also those of one of my predecessors, Sir Philip Knights, are encapsulated in our replies to questions asked of us when we appeared before the House of Commons Select Committee on Employment on Wednesday 27 February 1980. I said 'I would hope that despite all the problems that we have you will still allow us to have our discretion and you will not move towards the Army, CRS-type policing, or anything like that. -

22 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

22 bus time schedule & line map 22 Doncaster Town Centre <-> Worksop View In Website Mode The 22 bus line (Doncaster Town Centre <-> Worksop) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Doncaster Town Centre <-> Worksop: 5:58 AM - 10:50 PM (2) Langold <-> Worksop: 6:00 AM - 7:00 AM (3) Oldcotes <-> Worksop: 9:24 AM (4) Worksop <-> Doncaster Town Centre: 5:05 AM - 9:10 PM (5) Worksop <-> Tickhill: 10:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 22 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 22 bus arriving. Direction: Doncaster Town Centre <-> Worksop 22 bus Time Schedule 85 stops Doncaster Town Centre <-> Worksop Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday 9:55 AM - 10:50 PM Doncaster Frenchgate Interchange/A2, Doncaster Monday 5:58 AM - 10:50 PM Town Centre Food Mall, Doncaster Tuesday 5:58 AM - 10:50 PM Cleveland Street/St James Street, Doncaster Wednesday 5:58 AM - 10:50 PM Town Centre Thursday 5:58 AM - 10:50 PM Cleveland Street/Burden Close, Doncaster Town Friday 5:58 AM - 10:50 PM Centre Burden Close, Doncaster Saturday 5:58 AM - 10:50 PM Balby Road/Kelham Street, Balby Balby Road/Carr View Avenue, Balby 22 bus Info Balby Road/Burton Avenue, Balby Direction: Doncaster Town Centre <-> Worksop Stops: 85 Sandford Road/Balby Road, Balby Trip Duration: 66 min Line Summary: Doncaster Frenchgate Sandford Road/Surrey Street, Balby Interchange/A2, Doncaster Town Centre, Cleveland Street/St James Street, Doncaster Town Centre, Sandford Road/Woodƒeld Road, Balby Cleveland Street/Burden Close, Doncaster Town Centre, -

School Bus Timetables and Travel Advice for Pupils Of: WALES HIGH SCHOOL 2013/14 ACADEMIC YEAR

School Bus Timetables and Travel Advice for pupils of: WALES HIGH SCHOOL 2013/14 ACADEMIC YEAR 1 Bus services to/from School School services are listed below and full timetables can be found on the following pages. Please note details are correct as at 9th July, should any changes take place prior to the start of term these will be communicated via the school. Service Number Route details Operator 632 Worksop – Lindrick – South Anston – School 633 South Anston - School Norwood – Killamarsh – Upperthorpe – High Moor – Woodall – Harthill 634 – School Carlton - Gateford – Shireoaks – Netherthorpe - Thorpe Salvin – Harthill – 635 School 636 Laughton village – Dinnington – North Anston – Todwick – School School – Harthill – Todwick – North Anston – Dinnington – Thurcroft 637 (LATE Bus) 638 Thurcroft – Brampton en le Morthen - School 639 Thurcroft – Laughton Common - School Other services which pass within 400 metres of the school are listed below and full timetables of these services are available from the Travel Information Centre in Rotherham, Sheffield or Dinnington Interchange or can be downloaded at www.travelsouthyorkshire.com/timetables. Service Number Route details Operator Rotherham - Waterthorpe - Killamarsh - Norwood - School - Todwick - 27 Dinnington 29 Rotherham – Swallownest – School – Harthill Sheffield - Swallownest – School – South Anston – North Anston - X5 Dinnington Operator Contact Details: BrightBus – 01909 550480 – www.brightbus.co.uk First – 01709 566000 – www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/south_yorkshire/ Should you need any further advice on anything in this pack then please call Traveline on 01709 515151. NB: SYPTE accept no responsibility for information provided on any other providers websites. 2 Service change details From September significant changes will be made to services to/from the school. -

Seniors Directory

SENIORS DIRECTORY 1 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….3 GROUPS & CLUBS IN BASSETLAW……………………………4 DISTRICT-WIDE ………………………………………………………………………….4 AREA SPECIFIC………………………………………………………………………….7 BASSETLAW TENANTS AND RESIDENTS ASSOCIATIONS.19 CHURCHES & FAITH GROUPS IN BASSETLAW……………..19 SERVICES IN BASSETLAW………………………………………26 WHO CAN HELP ME ACCESS INFORMATION ON SERVICES TO KEEP ME SAFE AT HOME? ...................................................................................................26 HOW CAN I KEEP WARM AT HOME? ………………………………………….……27 WHERE CAN I GET HELP WITH MONEY? ………………………………………….27 WHERE CAN I GET PENSIONS ADVICE? …………………………………………..29 WHERE CAN I GET HELP WITH HEALTHCARE/FALLS? ………………………..29 HOW CAN I FIND OUT ABOUT HOUSING OPTIONS AND CHOICES? ………...31 WHERE ARE THE CARE HOMES IN BASSETLAW? ……………………………...32 WHERE CAN I GET ADVICE AND SUPPORT IF SUFFERING BEREAVEMENT? ………………………………………………………………………..36 WHERE CAN I GET A WHEELCHAIR? ………………………………………………36 WHO CAN HELP ME TO MANAGE MY LONG TERM CONDITION? …………….37 HOW CAN I GET SOME HELP WITH ADAPTATIONS AND SOCIAL CARE? ….37 WHERE CAN I GET SOME HELP AROUND THE HOME? ………………………...38 HOW CAN I GET OUT AND ABOUT? ………………………………………………...39 WHERE CAN I GET TRAVEL INFORMATION? ……………………………………..40 WHO CAN TELL ME ABOUT LOCAL GROUPS AND CLUBS? …………………..41 DO YOU WANT TO TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR YOUR OWN HEALTH AND KEEPING ACTIVE? ……………………………………………………………………...42 WHAT HEALTHY ACTIVITIES/LEISURE SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE? ………42 WHERE CAN I FIND GP REFERRAL OR CARDIAC REHABILITATION EXERCISE CLASSES? …………………………………………………………………45 -

Uk Coal Resources and New Exploitation Technologies

CAN NEW TECHNOLOGIES BE USED TO EXPLOIT THE COAL RESOURCES IN THE YORKSHIRE-NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COALFIELD? S Holloway1, N S Jones1, D P Creedy2 and K Garner2 1British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG 2Wardell Armstrong, Lancaster Building High Street, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire SP1 1PQ ABSTRACT Coal mining in the Yorkshire-Nottinghamshire Coalfield has been one of the region's most important industries over the last 150 years. The number of working mines peaked at over 400 in the late 19th and early part of the 20th Century. However, many have closed over the last few years and now there are only 10 large working mines still open. Three of these, Ricall/Whitemoor, Stillingfleet and Wistow, in the Selby complex, are due to close in April 2004. Although there are significant untouched coal resources east of the current deep mines, the prospects for opening new mines in the Yorkshire-Nottinghamshire coalfield appear very poor. Consequently, there has been a revival of interest in the potential for releasing some of the energy value of the remaining coal resources via alternative technologies such as coalbed methane production and underground coal gasification. Methane is already being drained from the few remaining deep mines and, in some cases, utilised as fuel for boilers or for electricity generation. The production of methane from abandoned mines is also taking place, but recent low electricity and gas prices have adversely affected its economics. There has not been any exploratory drilling for coalbed methane in the Yorkshire-Nottinghamshire coalfield, perhaps because the average seam methane content is somewhat lower than in some of the major coalfields on the west side of the country.