Surviving Art School. an Artist of Colour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

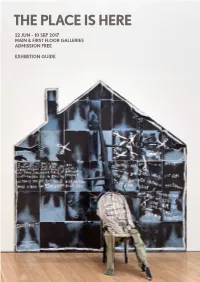

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE 15 August 2013 ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ by Kimathi Donkor 24 September – 24 November 2013 Admission Free Peckham Space, 89 Peckham High Street, London SE15 5RS Open: Wed-Fri 11 – 18.00 / Sat & Sun 11 – 17.00 (Closed: Mon & Tues) www.peckhamspace.com ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’, is an exhibition of new work by Kimathi Donkor and will be presented at Peckham Space, a contemporary art space in South London. Commissioned by Peckham Space, this exhibition will reflect on themes arising from Donkor’s engagement with local teenage black residents as they discovered the work of black British artists in the national collection at Tate Britain during workshops conducted earlier this Summer. There are 73,000 artworks in Tate’s collection, with about 15 of the 3,500 artists from both black and British identities – including Chris Ofili, Sonia Boyce, Donald Rodney, Frank Bowling and current Turner Prize nominee, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. For this exhibition and inspired by the experiences of these recent workshops, Donkor has created new large scale paintings that embody the his ongoing concerns with identity, aesthetics, agency and representation. Alongside these new paintings, visitors will be invited to participate in a museum-style ‘learning zone’ where numerous resources and materials will be available for visitors to further explore the works that were visited during the workshops and the wider representation of black British artists within the UK’s visual arts culture. There will also be opportunities to learn more about the experiences of the young people engaged in the project. -

PRESS RELEASE for Immediate Release 'Daddy, I Want to Be a Black

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ by Kimathi Donkor 24 September – 24 November 2013 Launch event 24 September 2013, 6-8:30pm Peckham Space, 89 Peckham High Street, London SE15 5RS Peckham Space presents ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’, an exhibition of new artwork by painter Kimathi Donkor, which reflects on themes arising from his engagement with teenage black residents of South London as they discovered the work of black British artists in the national collection at Tate Britain. There are 73,000 artworks in Tate’s collection, with about 15 of the 3,500 artists having both a black and a British identity – including Chris Ofili, Sonia Boyce, Donald Rodney, Frank Bowling and current Turner- Prize nominee, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. For this exhibition, Donkor has created a new series of paintings that embody the artist’s concerns with identity, aesthetics, agency and representation. The new paintings will be on display at Peckham Space and, alongside them, visitors will be invited to participate in an art museum-style ‘learning zone’ where books, computers, resources and materials will explore the work and representation of black British artists within the UK’s most prominent modern art institution – as well as the experiences of the young people engaged in the project. By offering this opportunity to learn more about these important works, it is hoped that they can be celebrated and their place in the national heritage reconsidered. The starting point for this commission was a series of workshops proposed by Kimathi Donkor for Leaders of Tomorrow, a leadership and enrichment programme for black teenagers of African and African-Caribbean heritage in Southwark. -

V&A R Esearch R Eport 2012

2012 REPORT V&A RESEARCH MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Research is a core activity of the V&A, helping to develop the public understanding of the art and artefacts of many of the great cultures of the world. This annual Research Report lists the outputs of staff from the calendar year 2012. Though the tabulation may seem detailed, this is certainly a case where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The V&A plays a synthetic role in binding together the fields of art, design and performance; conservation and collections management; and museum-based learning. We let the world know about our work through many different routes, which reach as large and varied an audience as possible. Here you will find some listings that you might expect - scholarly journal articles and books - but also television and radio programmes, public lectures, digital platforms. Many of these research outputs are delivered through collaborative partnerships with universities and other institutions. The V&A is international both in its collections and its outlook, and in this Report you will notice entries in French, Spanish, German, and Russian as well as English – and activities in places as diverse as Ukraine, Libya, and Colombia. Most importantly, research ensures that the Museum will continue to innovate in the years to come, and in this way inspire the creativity of others. Martin Roth ASIAN DEPARTMENT ASIAN ROTH, MARTIN JACKSON, ANNA [Foreword]. In: Olga Dmitrieva and Tessa Murdoch, The ‘exotic European’ in Japanese art. In: Francesco eds. The ‘Golden Age’ of the English Court: from Morena, ed. -

Claudette-Johnson-Exhibition-Notes

Upper Gallery 7. Figure in raw umber, 2018 12. Afterbirth, 1990 Piper Gallery 1. Standing Figure, 2017 Pastels on paper Pastel on paper 16. Reclining Figure, 2017 21. Untitled (with wool and leather), 1982 Acrylic paint, pastel and masking tape on paper Tate: Purchased 2019 Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Pastel and gouache paint on paper Pastel, gouache paint, silver paper, Rugby Art Gallery and Museum Gardens, London Halamish Collection, London leather and wool ‘Although I don’t believe that there is an Courtesy the artist and Hollybush essential truth that artists can convey through This work was included in Johnson’s important 2. Untitled (Yellow Blocks), 2019 1 7. And I Have My Own Business In This Gardens, London representation, I do believe that the fiction of 1992 solo exhibition at The Black-Art Gallery in Pastel and gouache paint on paper Skin, 1982 “blackness” that is the legacy of colonialism Finsbury Park, London, then led by Marlene Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Pastel and gouache paint on paper 22. Standing Figure with African Masks, 2018 can be interrupted by an encounter with the Smith, entitled In This Skin: Drawings by Gardens, London Museums Sheffield Pastel, gouache paint and ground on paper stories that we have to tell about ourselves.’ Claudette Johnson. A young Steve McQueen Tate: Purchased using funds provided by the ‘I wanted to look at how women occupy space. ‘Pushing the pastels around on oversized – Claudette Johnson reviewed the show, describing the works as 2018 Frieze Tate Fund supported by Endeavor I’d made a series of semi-abstract works sheets forces me to build the forms in a ‘overwhelmingly arresting. -

0-215 Artwork

The North*s Original Free Arts Newspaper + www.artwork.co.uk Number 215 Pick up your own FREE copy and find out what’s really happening in the arts Winter Issue 2020/21 ‘Autumn Light, Rig & Furrows’ – Watercolour from Mary Ann Rogers INSIDE: Covid-19: boom time for some Hornel – from Camera to Canvas artWORK 215 Winter Issue 2020/21 Page 2 artWORK 215 Winter Issue 2020/21 Page 3 ArtWork Special Feature A Smart Search Box can produce positive results at minimal cost! THE IMPORTANCE of would consistently deliver A Scrapbook of Images from the accurately searching online accurate and relevant results Kyle, Mallaig and Highland lines – Large format paperback, with 160 content of an organisation’s using various techniques which pages of glorious colour pictures of website could not be over- could include machine learning, steam in a Highland setting emphasised as it could help natural language processing and # 978 0905489 90 2 - Price : £9.99 enhance further interests in the artifi cial intelligence, to mention Northern Books from Famedram business and eventually increase a few. An effi cient search box www.northernbooks.co.uk the overall revenue could drastically reduce a no- For clarity, this is not show results display! about a global search engine For instance, most art artWORK optimisation for website galleries, museums and other traffi c nor an intrusive product art outlets could not detect a www.artwork.co.uk recommendation system, but simple anomaly in user inputs mainly about having a search which usually result in a “No West Highland box on a business website to results found!” scenario or just guarantee the display of relevant displaying erroneous lists of Wayfarer results to visitor’s queries on the records. -

Frieze Magazine | Shows | Kimathi Donkor

KIMATHI DONKOR SELECTED REVIEWS, INTERVIEWS, FEATURES AND VIDEO CONTENTS (click or scroll to navigate) Review by Mary Corrigall in The Times of South Africa, 2015 ……p2 Review by Lara Pawson in Frieze, 2012 ……p4 Review by Coline Milliard in Ar4nfo, 2012 ……p6 Review by Minna Salam in MsAfropolitan.com, 2012 ……p8 Review by Ashitha Nagesh in Art Forum, 2012 ……p10 Interview with Caroline Menezes in Studio Interna4onal, 2012 ……p11 Feature by Hazelanne Williams in The Voice, 2012 ……p16 The black ghosts haun1ng Downton Abbey by Lara Pawson in The Guardian, 2012 ……p19 Feature by Annie Rideout in Hackney Ci4zen, 2012 ……p21 Interview with YveKe Greslé, in FAD, 2013 . .…p24 Reading the Riot Act (extract) by Eddie Chambers in Visual Culture in Britain, 2013 ……p33 Kimathi Donkor’s Caribbean Passion: Hai= 1804 (extract) in The Hai4an Revolu4on in the Literary Imagina4on: Radical horizons, conserva4ve constraints. by Philip Kaisary, University of Virginia Press, 2014 ……p37 Links to online TV and video interviews ……p39 © All texts in this document are the copyright of their respec4ve authors Princess Politics - Women on top: Subverting subordination Mary Corrigall | 15 September, 2015 00:13 SITTING PRETTY: 'When Shall We 3?' by Kimathi Donkor When two Angolans stood in front of Kimathi Donkor's Kombi Continua (2010) on show at the 29th São Paulo Biennial, they gasped "It's our queen!" "They recognised [the figure] was Princess Nzinga before they read the capTon," said Donkor, siUng in an art studio next to Gallery Momo in Parktown North. It was a source of pride and delight for the BriTsh-born arTst of Ghanaian, Anglo-Jewish and Jamaican extracTon, as his painTngs transplant the famous African princess into contemporary clothes and scenes. -

Black British Art History Some Considerations

New Directions in Black British Art History Some Considerations Eddie Chambers ime was, or at least time might have been, when the writing or assembling of black British art histories was a relatively uncom- Tplicated matter. Historically (and we are now per- haps able to speak of such a thing), the curating or creating of black British art histories were for the most part centered on correcting or addressing the systemic absences of such artists. This making vis- ible of marginalized, excluded, or not widely known histories was what characterized the first substantial attempt at chronicling a black British history: the 1989–90 exhibition The Other Story: Asian, African, and Caribbean Artists in Post-War Britain.1 Given the historical tenuousness of black artists in British art history, this endeavor was a landmark exhibi- tion, conceived and curated by Rasheed Araeen and organized by Hayward Gallery and Southbank Centre, London. Araeen also did pretty much all of the catalogue’s heavy lifting, providing its major chapters. A measure of the importance of The Other Story can be gauged if and when we consider that, Journal of Contemporary African Art • 45 • November 2019 8 • Nka DOI 10.1215/10757163-7916820 © 2019 by Nka Publications Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/nka/article-pdf/2019/45/8/710839/20190008.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Catalogue cover for the exhibition Transforming the Crown: African, Asian, and Caribbean Artists in Britain 1966–1996, presented by the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, New York, and shown across three venues between October 14, 1997, and March 15 1998: Studio Museum in Harlem, Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute. -

Press Release the Place Is Here

PRESS RELEASE THE PLACE IS HERE Thu 22 Jun – Sun 10 Sep 2017 Donald Rodney, The House That Jack Built, 1987 Courtesy of Museums Sheffield. Photo Andy Keate. The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of culture remain vital today. The exhibition traces a number of conversations that took place between black artists, writers and thinkers as revealed through a broad range of creative practice. Against a backdrop of civil unrest and divisive national politics, they were exploring their relationship to Britain’s colonial past as well as to art history. Together, they show how a new generation of practitioners were positioning themselves in relation to different discourses and politics – amongst them, Civil Rights-era “Black art” in the US; Pan-Africanism; Margaret Thatcher’s anti-immigration policies and the resulting uprisings across the country; apartheid; black feminism; and the burgeoning field of cultural studies. Significantly, artists were addressing these issues by reworking and subverting a range of art-historical references and aesthetic strategies, from William Morris to Pop Art, documentary practices and the introduction of Third Cinema to the UK. As Lubaina Himid – one of the artists in the exhibition and from whose words the title is borrowed – wrote in 1985, “We are claiming what is ours and making ourselves visible”. -

Connecting Through Culture 2014–15 a Look Back

Connecting through culture 2014–15 A look back Welcome to this review of 2014–15, which highlights some of the ways in which, during the last year, arts and culture have supported King’s College London in its ambitions to deliver world-class education, an exceptional student experience and research that drives innovation, creates impact and engages beyond the university’s walls. Over the last three years, the university and skills. Over recent years, King’s ‘My experience at King’s would has developed symbiotic partnerships has supported the development of be far different, and probably far with artists and cultural organisations specialist teams at the interface between less enjoyable, without the cultural that enhance the King’s experience the university and the cultural sector. engagement I’ve been lucky enough to for academics and students while Much – although certainly not all – of have. It’s added richness to my studies adding value across the cultural sector. the achievement in the pages that follow by providing context and dimension From uniquely tailored teaching, owes a great deal to the hard work and to the books and articles and widening training and internship programmes, dedication of those teams and their my horizons beyond the lecture hall. to collaborative research projects and directors: Katherine Bond (Cultural The cultural events and institutions enquiries, to exhibitions and public Institute), Alison Duthie (Exhibitions I’ve engaged with have surprised me, events, arts and culture are helping to and Public Programming) and Daniel confused me, excited me and ignited generate new approaches, new insights Glaser (Science Gallery London). -

Download Delegate Pack

Reframing the moment LEGACIES OF 1982 BLK ART GROUP CONFERENCE hoto of Eddie Chambers by John Reardon 1980 p Saturday 27th October 2012 On Thursday 28th October 1982, a group of black art students hosted The First National Black Art Convention at Wolverhampton Polytechnic. Their purpose was to discuss ‘the form, function and future of black art’. Lecture Theatre Thirty years later almost to the Millenium Campus (MC) day, on Saturday 27th October 2012 artists, curators, art historians Building and academics gather, once again University of Wolverhampton in Wolverhampton, to share scholarship and research the Wulfruna St ‘black art movement’ of the 1980s, its core debates, precursors and WV1 1LY legacies. Reframing the moment legacies ofSaturday the 1982 Blk 27th Art GroupOctober Conference 2012 09:00 Registration Tea/Coffee Programme 09:45 Welcome & Introductions 10:00 Kobena Mercer: Keynote Perforations: Mapping the BLK Art Group into a diasporic model of art history by looking at ‘translations’ of US Black Arts Movement ideas and the prevalence of a cut-and-mix aesthetic. PART ONE 11:00 RAIDING THE ARCHIVE: introduced and moderated by Paul Goodwin Keith Piper Pathways to the 1980s In a video-essay first presented as work in progress at the February 2012 Blk Art Group Symposium, Keith Piper will present a brief history of the Blk Art Group and discuss the socio-political moment of 1980s that heralded the cultural explosion of UK born and educated black artists. Courtney J Martin Art and black consciousness In 1982, Rasheed Araeen was invited by the Wolverhampton Young Black Artists to speak at the First National Black Art Convention in Wolverhampton. -

Thin Black Line(S)

TATE BRITAIN 2011/2012 BRITAIN TATE THIN BLACK LINE(S) Sutapa Biswas Sonia Boyce Lubaina Himid THIN BLACK L THIN BLACK Claudette Johnson Ingrid Pollard I Veronica Ryan NE ( S ) Maud Sulter UCLAN A Making Histories Visible Project University of Central Lancashire TATE BRITAIN 2011/ 2012 THIN BLACK LINE(S) Sutapa Biswas Sonia Boyce Lubaina Himid Claudette Johnson Ingrid Pollard Veronica Ryan Maud Sulter TATE BRITAIN 2011/ 2012 CONTENTS Tate INTRODUCTION LETTERS to SUSAN THIN Black LINE(S) at Tate Britain ARTISTS Sutapa BISwaS SonIa Boyce LuBaIna HImId cLaudette JoHnSon InGRId poLLaRd VeRonIca Ryan maud SuLteR ARCHIVE Installation IN PROgRESS LINKS AND CONNECTIONS ACKNOwLEDgMENTS Published by Making Histories Visible Project, Centre For Contemporary Art © 2011 UCLAN INSERT Design by Red Square Design, Newcastle upon Tyne momentS and connectIonS – map All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN 978-0-9571579-0-3 TATE INTRODUCTION THIN BLACK LINE(S) Thin Black Line(s) Tate Britain 2011/12 In the early 1980s three exhibitions in London curated by Lubaina Himid Five Black Women at the Africa Centre (1983) Black Women Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre (1983-4) and The Thin Black Line at the Institute for Contemporary Arts in (1985) marked the arrival on the British art scene of a radical generation of young Black and Asian women artists.