Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Those Were the Difficult Years…”∗

UDC 343.261-051(=135.1)(497.11)"1916/1918"(093.3) 930.2:94(=135.1)(497)"1916/1918"(093.3) Original scientific work Panopoulou Kalliopi Aristotle University Of Thessaloniki Department of Physical Education and Sports' Science, Serres [email protected] “Those Were the Difficult Years…”∗ Oral accounts of Vlachophones from their captivity in Požarevac, Serbia Considering that the oral accounts of the people who experienced the events at a difficult period in time is the most important of all the other re- search material, I am attempting, with this article, to present a few phases of the captivity of the Vlachophones in Požarevac in 1916. The main ob- jective is to depict the climate of the era throughout the time frame from 1916 -- the commencement of their captivity outside Greece – and their re- turn in 1918, through the personal and collective experiences of ordinary people. It is an effort to highlight the value of the oral culture, incorporating the voice of the unseen protagonists into the historical data. It describes the way they reached this specific area, the two years they spent there, and the four phases of their return. Key words: Oral history, Collective memory, Vlachs, Captivity, Serres This announcement is the product of an on-the-spot study of the Vla- chophones of Serres, and more specifically refers to the Vlachophones of Irakleia (Tzoumagias), Petritsi, Vyroneia, and Poroion. It is founded mainly on oral ac- counts of first-generation individuals who witnessed the events of the captivity. The chief objective of this article is to depict the climate of the period from 1916 – the commencement of their captivity outside Greece – and their return in 1918, through the personal and collective experiences of ordinary people. -

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

1 Curriculum Vitae by Konstantinos Moustakas 1. Personal Details

Curriculum vitae by Konstantinos Moustakas 1. Personal details Surname : MOUSTAKAS Forename: KONSTANTINOS Father’s name: PANAGIOTIS Place of birth: Athens, Greece Date of birth: 10 October 1968 Nationality: Greek Marital status: single Address: 6 Patroklou Str., Rethymnon GR-74100, Greece tel. 0030-28310-77335 (job) e-mail: [email protected] 2. Education 2.1. Academic qualifications - PhD in Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK), 2001. - MPhil in Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK), 1993. - First degree in History, University of Ioannina (Greece), 1990. Mark: 8 1/52 out of 10. 2.2. Education details 1986 : Completion of secondary education, mark: 18 9/10 out of 20. Registration at the department of History and Archeology, University of Ioannina (Greece). 1990 (July) : Graduation by the department of History and Archeology, University of Ioannina. First degree specialization: history. Mark: 8 1/52 out of 10. 1991-1992 : Postgraduate studies at the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK). Program of study: MPhil by research. Dissertation title: Byzantine Kastoria. Supervisor: Professor A.A.M. Bryer. Examinors: Dr. J.F. Haldon (internal), Dr. M. Angold (external). 1 1993 (July): Graduation for the degree of MPhil. 1993-96, 1998-2001: Doctoral candidate at the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK). Dissertation topic: The Transition from Late Byzantine to Early Ottoman Southeastern Macedonia (14th – 15th centuries): A Socioeconomic and Demographic Study Supervisors: Professor A.A.M. Bryer, Dr. R. Murphey. Temporary withdrawal between 30-9-1996 and 30-9-1998 due to compulsory military service in Greece. -

The Aromanians in Macedonia

Macedonian Historical Review 3 (2012) Македонска историска ревија 3 (2012) EDITORIAL BOARD: Boban PETROVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editor-in-chief) Nikola ŽEŽOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Dalibor JOVANOVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Toni FILIPOSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Charles INGRAO, Purdue University, USA Bojan BALKOVEC, University of Ljubljana,Slovenia Aleksander NIKOLOV, University of Sofia, Bulgaria Đorđe BUBALO, University of Belgrade, Serbia Ivan BALTA, University of Osijek, Croatia Adrian PAPAIANI, University of Elbasan, Albania Oliver SCHMITT, University of Vienna, Austria Nikola MINOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editorial board secretary) ISSN: 1857-7032 © 2012 Faculty of Philosophy, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje, Macedonia University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius - Skopje Faculty of Philosophy Macedonian Historical Review vol. 3 2012 Please send all articles, notes, documents and enquiries to: Macedonian Historical Review Department of History Faculty of Philosophy Bul. Krste Misirkov bb 1000 Skopje Republic of Macedonia http://mhr.fzf.ukim.edu.mk/ [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 Nathalie DEL SOCORRO Archaic Funerary Rites in Ancient Macedonia: contribution of old excavations to present-day researches 15 Wouter VANACKER Indigenous Insurgence in the Central Balkan during the Principate 41 Valerie C. COOPER Archeological Evidence of Religious Syncretism in Thasos, Greece during the Early Christian Period 65 Diego PEIRANO Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala 85 Denitsa PETROVA La conquête ottomane dans les Balkans, reflétée dans quelques chroniques courtes 95 Elica MANEVA Archaeology, Ethnology, or History? Vodoča Necropolis, Graves 427a and 427, the First Half of the 19th c. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace, 1893-1912 By Martin Valkov Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Tolga Esmer Second Reader: Prof. Roumen Daskalov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The current thesis narrates an important episode of the history of South Eastern Europe, namely the history of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and its demand for political autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. Far from being “ancient hatreds” the communal conflicts that emerged in Macedonia in this period were a result of the ongoing processes of nationalization among the different communities and the competing visions of their national projects. These conflicts were greatly influenced by inter-imperial rivalries on the Balkans and the combination of increasing interference of the Great European Powers and small Balkan states of the Ottoman domestic affairs. I argue that autonomy was a multidimensional concept covering various meanings white-washed later on into the clean narratives of nationalism and rebirth. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

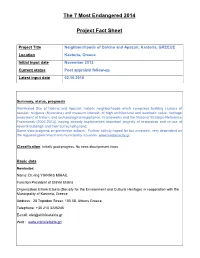

The 7 Most Endangered 2014 Project Fact Sheet

The 7 Most Endangered 2014 Project Fact Sheet Project Title Neighbourhoods of Dolcho and Apozari, Kastoria, GREECE Location Kastoria, Greece Initial input date November 2013 Current status Post appraisal follow-up Latest input date 02.10.2018 Summary, status, prognosis Nominated Site of Dolcho and Apozari, historic neighborhoods which comprises building clusters of secular, religious (Byzantine) and museum interest, of high architectural and aesthetic value, heritage monument of historic and archaeological importance. Frameworks and the National Strategic Reference Framework (2007-2013), having already implemented important projects of restoration and re-use of several buildings and their surrounding land. Some slow progress on preventive actions. Further activity hoped for but uncertain, very dependent on the regional government and municipality situation. www.kastoriacity.gr Classification: Initially good progress. No news about present times. Basic data Nominator: Name: Dr.-Ing YIANNIS MIHAIL Function President of Elliniki Etairia Organization Elliniki Etairia (Society for the Environment and Cultural Heritage) in cooperation with the Municipality of Kastoria, Greece Address : 28 Tripodon Street, 105 58, Athens Greece Telephone: +30 210 3225245 E-mail: [email protected] Web : www.ellinikietairia.gr/ Brief description: Historic neighborhoods with relevant examples of residential small buildings growing around small byzantine chapels and churches. Landscape and surrounding area with high heritage value. Owner: Public. (&Private), Bishopric (churches). 2013 data: Name: Municipality of Kastoria Administrator: (2013 data). The Municipality of Kastoria, with its own funds and resources and with European funds. Other partners: • The Regional Authority of Western Macedonia. Website: www.pdm.gov.gr • The 16th ΕΒΑ (Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities). • The Technical Chamber of Greece (ΤΕΕ). -

Pisa : Plus-Pisa University Press, 2008

Frontiers and identities : cities in regions and nations / edited by Lud’a Klusáková and Laure Teulières. - Pisa : Plus-Pisa university press, 2008. – (Thematic work group. 5, Frontiers and identities; 3) 302.5 (21.) 1. Individuo e società 2. Identità <psicologia sociale> I. Klusáková, Lud’a II. Teulières, Laure CIP a cura del Sistema bibliotecario dell’Università di Pisa This volume is published thanks to the support of the Directorate General for Research of the European Commission, by the Sixth Framework Network of Excellence CLIOHRES.net under the contract CIT3-CT-2005-006164. The volume is solely the responsibility of the Network and the authors; the European Community cannot be held responsible for its contents or for any use which may be made of it. Cover: Paul Klee (1879-1940), Rocky Coast, 1931, oil on plywood, Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Elke Walford. ©2005. Photo Scala, Florence/Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin © 2008 CLIOHRES.net The materials published as part of the CLIOHRES Project are the property of the CLIOHRES.net Consortium. They are available for study and use, provided that the source is clearly acknowledged. [email protected] - www.cliohres.net Published by Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press Lungarno Pacinotti, 43 56126 Pisa Tel. 050 2212056 – Fax 050 2212945 [email protected] www.edizioniplus.it - Section “Biblioteca” Member of ISBN: 978-88-8492-556-5 Linguistic revision Kieran Hoare, Rhys Morgan, Gerald Power Informatic editing Răzvan Adrian Marinescu From Christians to Members of an Ethnic Community: Creating Borders in the City of Thessaloniki (1800-1912) Iakovos D. Michailidis Aristotle University of Thessaloniki ABSTRACT The chapter focuses on the division of the Christian millet of the city of Thessaloniki into different and ambivalent ethnic groups during the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. -

The Attitude of the Communist Party of Greece and the Protection of the Greek-Yugoslav Border

Spyridon Sfetas Autonomist Movements of the Slavophones in 1944: The Attitude of the Communist Party of Greece and the Protection of the Greek-Yugoslav Border The founding of the Slavo-Macedonian Popular Liberation Front (SNOF) in Kastoria in October 1943 and in Florina the following November was a result of two factors: the general negotiations between Tito's envoy in Yugoslav and Greek Macedonia, Svetozar Vukmanovic-Tempo, the military leaders of the Greek Popular Liberation Army (ELAS), and the political leaders of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) in July and August 1943 to co-ordinate the resistance movements; and the more specific discussions between Leonidas Stringos and the political delegate of the GHQ of Yugoslav Macedonia, Cvetko Uzunovski in late August or early September 1943 near Yannitsa. The Yugoslavs’ immediate purpose in founding SNOF was to inculcate a Slavo- Macedonian national consciousness in the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia and to enlist the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia into the resistance movement in Yugoslav Macedonia; while their indirect aim was to promote Yugoslavia's views on the Macedonian Question. The KKE had recognised the Slavophones as a "SlavoMacedonian nation" since 1934, in accordance with the relevant decision by the Comintern, and since 1935 had been demanding full equality for the minorities within the Greek state; and it now acquiesced to the founding of SNOF in the belief that this would draw into the resistance those Slavophones who had been led astray by Bulgarian Fascist propaganda. However, the Central Committee of the Greek National Liberation Front (EAM) had not approved the founding of SNOF, believing that the new organisation would conduce more to the fragmentation than to the unity of the resistance forces. -

The Struggle of Hellenism Over Macedonia

THE STRUGGLE OF HELLENISM OVER MACEDONIA A SURVEY OF RECENT BIBLIOGRAPHY The rise of nationalities, European power politics and the impending dissolution of the Ottoman empire had converted the Balkans at the end of last and the beginning of this century into a field of fierce national antagonism. Events, especially in that vast area of the peninsula, geogra phically from very remote times known by the name of Macedonia, had gone far beyond the Turkish state’s boundaries and had become matters of international concern. "The Macedonian Question” drew at one time the attention of public opinion all over Europe and, up to this moment, presents a most interesting subject to the scholar of Balkan history. From the Greek side, the Macedonian Question has been nothing but the compulsory struggle of Hellenism to keep its position against Bulgarian infiltration strongly agitated by foreign power politics; the outcome of the struggle is primarily due to the overwhelmingly in all respects superiority of the Greek element in the disputed area, its vitality and will for resistance. The assistance given by the Kingdom of Greece at the last stage of the fight (1904- 1908) would have otherwise been fruitless. An effort to study this subject from a more general scope has re cently been undertaken under the auspices of the Institute f or Balkan Studies of the Society for Macedonian Studies in Thessalonike. The effort includes the collection of all published or unpublished material, of manuscripts, handwritten notes, letters, photographs, newspapers of that time, official consular reports, Turkish documents etc. and their examination by a special staff. -

The Truth About Greek Occupied Macedonia

TheTruth about Greek Occupied Macedonia By Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Truth about Greek Occupied Macedonia Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition January 7, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE – Struggle for our own School and Church .......8 1. Macedonian texts written with Greek letters .................................9 2. Educators and renaissance men from Southern Macedonia.........15 3. Kukush – Flag bearer of the educational struggle........................21 4. The movement in Meglen Region................................................33 5. Cultural enlightenment movement in Western Macedonia..........38 6. Macedonian and Bulgarian interests collide ................................41 CHAPTER TWO - Armed National Resistance ..........................47 1. The Negush Uprising ...................................................................47 2. Temporary Macedonian government ...........................................49