Formation of Priests-Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage Through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-In-Community

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-in-Community Kent Lasnoski Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Lasnoski, Kent, "Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-in-Community" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 98. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/98 RENEWING A CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF MARRIAGE THROUGH A COMMON WAY OF LIFE: CONSONANCE WITH VOWED RELIGIOUS LIFE-IN- COMMUNITY by Kent Lasnoski, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABSTRACT RENEWING A CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF MARRIAGE THROUGH A COMMON WAY OF LIFE: CONSONANCE WITH VOWED RELIGIOUS LIFE-IN-COMMUNITY Kent Lasnoski Marquette University, 2011 Beginning with Vatican II‘s call for constant renewal, in light of the council‘s universal call to holiness, I analyze and critique modern theologies of Christian marriage, especially those identifying marriage as a relationship or as practice. Herein, need emerges for a new, ecclesial, trinitarian, and christological paradigm to identify purposes, ends, and goods of Christian marriage. The dissertation‘s body develops the foundation and framework of this new paradigm: a Common Way in Christ. I find this paradigm by putting marriage in dialogue with an ecclesial practice already the subject of rich trinitarian, christological, ecclesial theological development: consecrated religious life. -

THE SUPREME LOVE of the RELIGIOUS HEART: HEART of JESUS Sr

Teachings of SCTJM - Sr. Christine Hernandez, SCTJM THE SUPREME LOVE OF THE RELIGIOUS HEART: HEART OF JESUS Sr. Christine Hernandez, SCTJM The heart of a religious is a heart only for God, it is an undivided heart; a heart that seeks, in everything, to do the will of God. “The religious vocation in essence is a call of love and for love.”1 There is a covenant of spousal love between a religious heart and God. God calls, one willingly answers entering into a mystery of spousal union. This answering or responding creates a special relationship between Jesus’ Heart and a religious heart; “an answer of love: a love of self-giving, which is the heart of consecration, of the consecration of the person.”2 The call of God is a call of love and the response is a response of love. It is an election made by God, calling some to a closer more intimate following of Christ. When God calls a heart, the heart is so deeply moved that it begins to see ordinary things in a new light. Things that were once important are replaced by things of God; gently, but clearly God begins to covet a heart, draw it closer to Himself, “so I will allure her; I will lead her to the desert and speak to her heart.”3 While He does this, through the Holy Spirit, He pours out all the graces necessary for a response of love; for the response He seeks but will never impose; for the “fiat” of Mary. The heart grows in such love for God and the things of God; it says “I will do what you ask of me simply out of love for you.” It renounces its life, loved ones, career, pets and anything that stands in the way of this spousal union with God; “charity took possession of my soul and filled me with the spirit of self- forgetfulness, and from that time I was always happy.”4. -

The Holy See

The Holy See PASTORAL JOURNEY TO BENIN, UGANDA AND KHARTOUM (SUDAN) OPENING SESSION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE SYNOD OF BISHOPS FOR THE SPECIAL ASSEMBLY FOR AFRICA ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS JOHN PAUL II Cathedral of Rubaga Archdiocese of Kampala (Uganda) Tuesday, 9 February 1993 Dear Brother Bishops, Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, 1. It is with "joi inspired by the Holy Spirit" that we gather in this Cathedral of the Archdiocese of Kampala for the opening session of the Council of the General Secretariat of the Synod of Bishops for the Special Assembly for Africa. This is the seventh meeting of the Council and the third to take place on this Continent. I offer cordial greetings to all its members and to the other Bishops who have joined us. This occasion has profound significance not only for the local Churches in Africa but also for the People of God throughout the world. Through my presence here I wish to support both what has already been accomplished and what will be achieved in the days ahead. Praying Vespers together we give visible expression to the bonds of communion which unite the See of Peter and the particular Churches on this Continent, and the reality of that collegialitas effectiva et affectiva gives intensity to our prayer for the African Bishops as they prepare with their flocks for the Special Synodal Assembly. With deep affection in our Lord Jesus Christ, I wish to greet the representatives of the priests, men 2 and women Religious, and seminarians of the Dioceses of Uganda who are with us this evening. -

Gerard Mannion Is to Be Congratulated for This Splendid Collection on the Papacy of John Paul II

“Gerard Mannion is to be congratulated for this splendid collection on the papacy of John Paul II. Well-focused and insightful essays help us to understand his thoughts on philosophy, the papacy, women, the church, religious life, morality, collegiality, interreligious dialogue, and liberation theology. With authors representing a wide variety of perspectives, Mannion avoids the predictable ideological battles over the legacy of Pope John Paul; rather he captures the depth and complexity of this extraordinary figure by the balance, intelligence, and comprehensiveness of the volume. A well-planned and beautifully executed project!” —James F. Keenan, SJ Founders Professor in Theology Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts “Scenes of the charismatic John Paul II kissing the tarmac, praying with global religious leaders, addressing throngs of adoring young people, and finally dying linger in the world’s imagination. This book turns to another side of this outsized religious leader and examines his vision of the church and his theological positions. Each of these finely tuned essays show the greatness of this man by replacing the mythological account with the historical record. The straightforward, honest, expert, and yet accessible analyses situate John Paul II in his context and show both the triumphs and the ambiguities of his intellectual legacy. This masterful collection is absolutely basic reading for critically appreciating the papacy of John Paul II.” —Roger Haight, SJ Union Theological Seminary New York “The length of John Paul II’s tenure of the papacy, the complexity of his personality, and the ambivalence of his legacy make him not only a compelling subject of study, but also a challenging one. -

The Virgin Mary in the Breadth and Scope of Interreligious Dialogue

Marian Studies Volume 47 Marian Spirituality and the Interreligious Article 7 Dialogue 1996 The irV gin Mary in the Breadth and Scope of Interreligious Dialogue John Borelli Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Borelli, John (1996) "The irV gin Mary in the Breadth and Scope of Interreligious Dialogue," Marian Studies: Vol. 47, Article 7. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol47/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Borelli: Mary in Interreligious Dialogue TilE VIRGIN MARY IN TilE BREADTH AND SCOPE OF INTERREUGIOUS DIALOGUE john Borelli, Ph.D.* Interreligious Relations as Catholic Context "Interreligious relations today are clearly at the heart of the Catholic Church's life and ministry and will increase in signifi cance as we move into the third millennium of Christianity." With this statement, Bishop Joseph J. Gerry, Episcopal Mod erator for Interreligious Relations, National Conference of Catholic Bishops [NCCB], begins a recently published article entitled "The Commitment of the Catholic Church to Interreli gious Relations:' 1 He shows how this is obvious from events during the pontificate of Pope John Paul n. Indeed, serving as an example to the whole church, the pope has converted -

Priestly Formation According to Pastores Dabo Vobis* 1

305 ❚Special Issues❚ □ Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts Priestly Formation According to Pastores Dabo Vobis* 1 Fr. Thomas Cheruparambil 〔St. Joseph Pontifical Seminary, India〕 Introduction 1. Historical Antecedents of Pastores Dabo Vobis 2. The 1990 Synod of Bishops: Some Particulars 3. Highlights on the Priestly Formation in Pastores Dabo Vobis 4. Biblical Foundation of Priesthood 5. Priestly Vocation and the Challenges of Priestly Formation 6. Human Formation 7. Spiritual Formation 8. Intellectual Formation 9. Pastoral Formation 10. Agents of Priestly Formation 11. Ongoing Formation of Priests Conclusion Introduction Jesus the high priest began his public ministry with the following proclamation: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed *1이 글은 2015년 ‘재단법인 신학과사상’의 연구비 지원을 받아 연구·작성된 논문임. 306 Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Lk 4:18, 19). Jesus was filled with the Holy Spirit before his public ministry. All Christian faithful, irrespective of their sate of vocation are called to attain perfection and sanctity. As there are different kinds of vocations, the way to Christian perfection also differs. Every vocation and ministry is specific in its nature. Accordingly, one may speak about the specificity of priestly ministry and formation. In this connection, one may ask: what is the specific nature of priestly formation keeping in mind the specific nature of priestly ministry? There may be different views and opinions about priestly formation. -

The Consecrated Life

THE CONSECRATED LIFE: A SHARE IN THE TOTAL GIFT OF THE HOLY SPIRIT [An Oblation to the Father, of the Kenosis of the Son, in the Total Gift of the Holy Spirit - in the Recent Magisterial Teaching] Rev. Joseph C. Henchey, CSS 2000 CONSECRATED LIFE 2 THE CONSECRATED LIFE: A SHARE IN THE TOTAL GIFT OF THE HOLY SPIRIT [An Oblation to the Father, of the Kenosis of the Son, in the Total Gift of the Holy Spirit - in the Recent Magisterial Teaching] Introduction : In the universal call to holiness addressed to the entire Church, the central Model of it all is the Most Blessed Trinity, made known to us through the exclusive Self-giving of Jesus Christ: "... The Church, whose mystery is set forth by this Sacred Council, is held, as a matter of faith, to be unfailingly holy. This is because Christ, the Son of God, who with the Father and the Spirit is hailed as 'alone holy'. loved the Church as His Bride , giving himself up for her so as to sanctify her [cf. Ep 5:25-26]..." [LG 39]. The "nuptial theme”, epitomized by Mary and Joseph, is recalled repeatedly in the Apostolic Exhortation, Redemptoris Custos [August 15, 1989]: "... Thus, before Joseph lived with Mary, he was already her 'husband'. Mary, however, preserved her deep desire to give herself exclusively to God . One may well ask how this desire of Mary's could be reconciled with a 'wedding.' The answer can come only from the saving events as they unfold, from the special action of God Himself. -

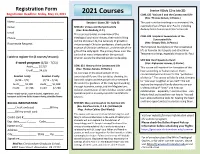

2021 Registration Form

Registration Form Session II (July 12 to July 23) Registration Deadline: Friday, May 14, 2021 2021 Courses CONL 625 Vatican II and the Consecrated Life (Rev. Thomas Nelson, O.PRAEM.) Name ________________________________ Session I (June 28 – July 9) The post-conciliar teaching on consecrated life, Order ________________________________ SPIR 634 Virtues and the Spiritual Life especially that of Pope John Paul II, including (Rev. Brian Mullady, O.P.) Redemptionis Donum and Vita Consecrata. Email________________________________ This course provides an overview of the theological and moral virtues, their role in living CONL 623 Scriptural Foundations of the Phone _______________________________ Consecrated Life out the Christian life, the necessity of growth in (Rev. Gregory Dick, O.PRAEM.) Roommate Request: virtue to reach Christian perfection, charity as the essence of Christian perfection, and the role of the The Scriptural foundations of the consecrated _____________________________________ gifts of the Holy Spirit. The primary focus is on the life as found in the Gospels and other New cardinal or moral virtues which the spiritual Testament writings, especially those of St. Paul. I wish to register for (2 courses/session): director assists the directed person to develop. SPIR 803 Heart Speaks to Heart 4-week program (6/28 - 7/23) (Rev. Alphonsus Hermes, O.PRAEM.) CONL 621 History of the Consecrated Life Audit____ $2,310 This course will examine the formation of the (Rev. Thomas Nelson, O.PRAEM.) Credit____ $4,526 heart according to human -

ABSTRACT Toward a Protestant Theology of Celibacy: Protestant Thought in Dialogue with John Paul II's Theology of the Body Ru

ABSTRACT Toward a Protestant Theology of Celibacy: Protestant Thought in Dialogue with John Paul II’s Theology of the Body Russell Joseph Hobbs, M.A., D.Min. Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. This dissertation examines the theology of celibacy found both in John Paul II’s writings and in current Protestant theology, with the aim of developing a framework and legitimation for a richer Protestant theology of celibacy. Chapter 1 introduces the thesis. Chapter 2 reviews the Protestant literature on celibacy under two headings: first, major treatments from the Protestant era, including those by Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Wesley, various Shakers, and authors from the English Reformation; second, treatments from 1950 to the present. The chapter reveals that modern Protestants have done little theological work on celibacy. Self-help literature for singles is common and often insightful, but it is rarely theological. Chapter 3 synthesizes the best contemporary Protestant thinking on celibacy under two headings: first, major treatments by Karl Barth, Max Thurian, and Stanley Grenz; second, major Protestant themes in the theology of celibacy. The fourth chapter describes the foundation of John Paul II’s theology of human sexuality and includes an overview of his life and education, an evaluation of Max Scheler’s influence, and a review of Karol Wojtyla’s Love and Responsibility and The Acting Person . Chapter 5 treats two topics. First, it describes John Paul II’s, Theology of the Body , and more particularly the section entitled “Virginity for the Sake of the Kingdom.” There he examines Jesus’ instruction in Matt 19:11-12, celibacy as vocation, the superiority of celibacy to marriage, celibacy as redemption of the body, Paul’s instructions in 1 Cor 7, and virginity as human destiny. -

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II This section entails the writings of Pope John Paul II starting with his Pontificate in October 16, 1978. In this section, one will find the Holy Father's Encyclicals, Apostolic Constitutions and Letters, exhortations and addresses published in different languages. John Paul II. Address to Presidents of Catholic Colleges and Universities (at Catholic University). (October 7, 1979): 163-167. -----. Address to the General Assembly of the United Nations, October 2, 1980, 16-30. -----. "Address to the Youth of Paris. (June 1, 1980)," L'Osservatore Romano (English Edition), (June 16, 1980): 13. -----. Affido a Te, O Maria. Ed. Sergio Trassati and Arturo Mari. Bergamo: Editrice Velar, 1982. -----. Africa: Apostolic Pilgrimage. Boston: St. Paul Editions, 1980. -----. Africa: Land of Promise, Land of Hope. Boston: St. Paul Editions, 1982. -----. Amantissima Providentia, Apostolic Letter, 1980. -----. The Apostles of the Slavs (Commemorating Sts. Cyril and Methodius): Fourth Encyclical Letter, June 2, 1985. Washington D. C.: Office for Publishing and Promotion Services. United States Catholic Conference, 1985. -----. Augustinum Hipponensem. August 28, 1986. Boston: St. Paul Editions, 1986. -----. "Behold Your Mother," Holy Thursday Letter of John Paul II, Boston: St. Paul Editions, 1988. -----. Brazil: Journey in the Light of the Eucharist. Boston: St. Paul Editions, 1980. -----. Il Buon Pastore: Scritti, Disorsi e Lettere Pastorali. Trans. Elzbieta Cywiak and Renzo Panzone. Rome Edizioni Logos, 1978. -----. Catechesi Tradendae, On Catechesis in Our Time. Boston: St. Paul Editions, 1979. -----. Centesimus Annus (Commemorating the Centenary of Rerum Novarum by Leo XIII): Ninth Encyclical Letter, May 1, 1991. Washington D. C.: Office for Publishing and Promotion Services, United States Catholic Conference, 1991. -

Growth in Holiness

Growth in Holiness Antidote to Contraceptive Mentality in Family Life, and Lack of Totality in Religious Life - Humanae Vitae 1968: and Sustained Hope for Growth in Holiness [Conference given at St. Mary of the Lake Seminary – Mundelein IL - 25th Anniversary of Humanae Vitae - Easter 1993] Rev. Joseph Henchey, CSS 1993 GROWTH IN HOLINESS 2 Growth in Holiness: Antidote to Contraceptive Mentality in Family Life, and Lack of Totality in Religious Life - Humanae Vitae 1968: and Sustained Hope for Growth in Holiness [Conference given at St. Mary of the Lake Seminary - Mundelein IL - 25th Anniversary of Humanae Vitae - Easter 1993] Rev. Joseph Henchey, CSS Introduction Twenty-five years have passed His Holiness, Pope Paul VI, was writing his authoritative Encyclical, Humanae Vitae [July 25,1968]. This document was written in the full light of the recently concluded Second Vatican Council, with its central document, Lumen Gentium [November 21, 1964], with its special emphasis on The Universal Call to Holiness [Chapter 5, ## 39-41]. In this reflection, the ideals presented in this context will be studied as they have had a bearing on the consecrated life. The nuptial theme and the total self- giving of Jesus Christ have often been presented in varying contexts, but most particularly to those striving to live a consecrated way of life, following Christ in the evangelical counsels, persevering in celibacy. There has been a steady flow of authoritative teaching from the official Magisterium of the Church. These documents offer a realistic, challenging and sustained hope for the re-discovery of the values of religious life, as we prepare to enter the Third Millennium. -

Gaudium Et Spes As a Blueprint for the Culture of Life

Gaudium et Spes as a Blueprint for the Culture of Life Robert F. Gotcher DURING the 1980s when I started getting involved in pro-life activities, there was a sometimes-heated debate about which was more important or essential to the pro-life cause: prayer, direct action, or political activity. Political activists were sometimes criticized by advocates of direct action and spiritual warfare for relying too heavily on man and not enough on God or for neglecting those who were in fact being killed each day. The political activists, on the other hand, sometimes criticized those engaged in direct action for undermining the progress made on the political front because of what was seen by some as extremism or because of the isolated incidents of violence. These three approaches–prayer, direct action, and political action– overlap, of course. There were and continue to be reconcilers, those who hold that each approach has its value and is part of the overall effort to save the lives of the unborn. I tend to side with the reconcilers in these discussions. However, reflection over the years has led me to believe that even the reconciling position, while true, is inadequate. The three approaches (prayer, direct action, political action) are not simply three independent approaches to pro-life activism but need to be integrated into an overall promotion of a culture of life. The growth of the term “culture wars” in the 1990s leads me to believe that many others are coming to the same conclusion. I am not implying that my growth in appreciation of this fact is a fruit of my own insight.