A Walk from Wapping to Canary Wharf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Tower Hamlets Local Plan Topic Paper: Views & Landmarks 1 Introduction & Background

Tower Hamlets Local Plan Topic Paper: Views & Landmarks 1 Introduction & background This section will cover the purpose of the topic paper, what it covers and the process it has followed. 1.1 Introduction to the Local Plan The new Local Plan is a key strategic document which will set the framework for the future development and growth of Tower Hamlets over the period from 2016 to 2031. The draft Tower Hamlets Local Plan went out to consultation over a period of 6 weeks from Monday 2 October 2017 and to Monday 12 November 2017 (known as the regulation 19 stage). The regulation 19 version of the Local Plan (along with relevant supporting documents and the representations) can be found from the examination library page on our website via the following link: https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/lgnl/council_and_democracy/consultations/past_consultations/Lo cal_Plan.aspx. 1.2 Role & purpose This topic paper has been produced to accompany the submission of the Local Plan to the secretary of state before it undergoes a public examination. It will: . Provide more detail and explanation about how we have arrived at our approach and the assumptions and information we have used that underpin that approach. Respond to representations received during the regulation 19 consultation. 1.3 Scope This paper covers the following topics: . Inventory of views and landmarks identified in conservation area appraisals and management plans. Identification of elements of the borough’s townscape elements which are present in London Views Management Framework. Justification for designations of borough views and borough landmarks. Local Plan Topic Paper D.DH4 Managing and Shaping Views Page 1 of 23 2 Legislative & policy context This section will set out the context in which the policies in the Local Plan have been developed. -

Annual Review 2020

BRINGING YOU CLOSER ANNUAL REVIEW 2019/20 WHO WE ARE EECF was established in 1990 by the London Docklands Development Corporation as its forward strategy for continued community investment. Vision A philanthropic East End free of poverty. Mission To drive philanthropy and charitable giving that responds to community needs and aspirations in East London, both now and in the future. Bringing you closer to the... Challenges Facts People Outcomes 2 WELCOME We started the year, as always, with the ambition of surpassing our successes of the previous 12 months. As the year headed to a close, we had achieved that goal and were ready to celebrate our achievements just as COVID-19 arrived. Our plans were put on hold and in true East End fashion we responded with passion, determination and most recognisably, resilience. Within 48 hours of lockdown we had launched our Emergency Fund and just days later we were providing much needed financial support to local charities serving our most vulnerable residents. I am delighted with what we have achieved and I would like to pay tribute to our donors, volunteers and key workers delivering essential community services. Our success is a result Howard Dawber of a huge community effort. We can all be extremely proud of our achievements. In the first Chairman three months of 2020/21 we distributed over £630,000 that reached thousands of residents experiencing hardship. The fund will continue to run throughout the year, adapting to emerging community needs, as there is still much more to do. The East End will pull through, as it always does, but the virus has shone a spotlight on a number of acute issues – loneliness, mental health, digital exclusion and food poverty among others. -

Cinnabar Wharf Central, 24 Wapping High Street, London, E1w 1Nq

CINNABAR WHARF CENTRAL, 24 WAPPING HIGH STREET, LONDON, E1W 1NQ Furnished, £1,250 per week + £276 inc VAT one off admin and other charges may apply.* Available Now FLAT 60 CINNABAR WHARF CENTRAL, 24 £1,250 per week Furnished reception room • kitchen • 3 bedrooms • 3 bathrooms • balcony with views of the River Thames • parking • 24hr porterage • administrative EPC Rating = charges D apply Council Tax = H Description A well appointed 3 bedroom apartment in this prestigious development close to St. Katharine’s Dock and Tower Hill. The apartment benefits from a river facing wrap around balcony, higher tiered mezzanine which offer views over Tower Bridge. The property further benefits from private parking and 24hr security. The City, Canary Wharf and West End are conveniently accessed via Wapping and Tower Hill underground stations. Energy Performance A copy of the full Energy Performance Certificate is available on request. Viewing Strictly by appointment with Savills. FLOORPLANS Gross internal area: 0 sq ft, m² Gross external area: FILL IN *Admin fees including drawing up the tenancy agreement, reference charge for one tenant – £276 inc VAT. £36 inc VAT for each additional tenant, occupant, guarantor reference where required. Inventory check-out fee – charged at end of tenancy. Third party charge dependant on property size and whether furnished/unfurnished/part furnished and the company available at the time. Deposit – usually equivalent to 6 weeks rent, though may be greater subject to mutual agreement. Pets – additional Savills Wapping deposit required generally equivalent to two weeks rent. For more details, visit savills.co.uk/fees. Kristina Dabrila Important notice: Savills, their clients and any joint agents give notice that: 1: They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties in relation to the property either here or elsewhere, [email protected] either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise. -

Pepys Greenwich Walk

Samuel Pepys’ Walk through the eastern City of London and Greenwich Distance = 5 miles (8 km) Estimated duration = 3 – 4 hours not including the river trip to Greenwich Nearest underground stations: This is planned to start from the Monument underground station, but could be joined at several other places including Aldgate or Tower Hill underground stations. You can do this Walk on any day of the week, but my recommendation would be to do the first part on a Wednesday or a Thursday because there may be free lunchtime classical recitals in one of the churches that are on the route. The quietest time would be at the weekend because the main part of this Walk takes place in the heart of the business district of London, which is almost empty at that time. However this does mean that many places will be closed including ironically the churches as well as most of the pubs and Seething Lane Garden. It’s a good idea to buy a one-day bus pass or travel card if you don’t already have one, so that you needn’t walk the whole route but can jump on and off any bus going in your direction. This is based around the Pepys Diary website at www.pepysdiary.com and your photographs could be added to the Pepys group collection here: www.flickr.com/groups/pepysdiary. And if you aren't in London at present, perhaps you'd like to attempt a "virtual tour" through the hyperlinks, or alternatively explore London via google streetview, the various BBC London webcams or these ones, which are much more comprehensive. -

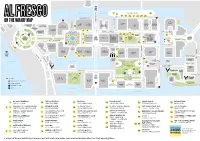

On the Wharf

W W HERTSMERE ROAD ROAD HERTSMERE E E S S T T F F E E R R DLR R R Y Y R R WEST O O INDIA A A QUAY D D NORTH DOCK NORTH DOCK 17 CROSSRAIL PLACE 25 ONTARIO WAY 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 ADAMS PLAZA BRIDGE ADAMS FISHERMAN'S WALK 17 COLUMBUS COURTYARD ONE ON THE WHARF MAP PASSAGE FROBISHER CHURCHILL 5 CANADA PLACE 10 CABOT 5 NORTH SQUARE 15 CANADA 30 NORTH 1 WESTFERRY COLUMBUS SQUARE COLONNADE 25 NORTH 8 CANADA SQUARE COLONNADE CIRCUS COURTYARD ONE 10 COLONNADE SQUARE CABOT SQUARE WREN LANDING 7 WESTFERRY CIRCUS 20 COLUMBUS COURTYARD 4 8 11 WESTFERRY CABOT SQUARE NORTH COLONNADE NORTH COLONNADE CIRCUS 9 28 29 27 26 THE IVY IN THE PARK 16-19 CANADA 32 1 5 SQUARE ONE DLR THE CANADA WAITROSE & CARTIER WESTFERRY CABOT PLACE CABOT PLACE CANADA PARK 31 SQUARE 34 PARTNERS CHURCHILL 2 CANARY SQUARE PAVILION PARK THIRD SPACE PLACE CIRCLE CIRCUS WHARF CHURCHILL PLACE WEST INDIA AVENUE PLATEAU 33 3 7 6 30 35 15 WESTFERRY ONE WEST CABOT SQUARE SOUTH COLONNADE UPPER BANK STREET SOUTH COLONNADE CIRCUS INDIA AVENUE FUTURE DEVELOPMENT 15 CUBITT STREET CHARTER STEPS NASH COURT 37 25 CABOT 20 CABOT 10 SOUTH 30 SOUTH 20 CANADA 25/30 SQUARE SQUARE COLONNADE COLONNADE 33 CANADA 25 CANADA SQUARE CHURCHILL 11 SQUARE SQUARE PLACE CANARY W WHARF E S PIER T F W 12 13 BERNERS PLACE E R E 16 38 R S Y T F STREET MONTGOMERY 15 WATER 30 HARBORD R E JUBILEE 36 OFFICE O R PLAZA MARKETING 1 WATER STREET SQUARE A R D Y 640 SUITE STREET MIDDLE DOCK RIVER THAMES R EAST O NEWFOUNDLAND UNDERGROUND UNDERGROUND MONTGOMERY A WATER STREET D SQUARE 12 BANK JUBILEE PARK UNDERGROUND WATER -

The Custom House

THE CUSTOM HOUSE The London Custom House is a forgotten treasure, on a prime site on the Thames with glorious views of the river and Tower Bridge. The question now before the City Corporation is whether it should become a luxury hotel with limited public access or whether it should have a more public use, especially the magnificent 180 foot Long Room. The Custom House is zoned for office use and permission for a hotel requires a change of use which the City may be hesitant to give. Circumstances have changed since the Custom House was sold as part of a £370 million job lot of HMRC properties around the UK to an offshore company in Bermuda – a sale that caused considerable merriment among HM customs staff in view of the tax avoidance issues it raised. SAVE Britain’s Heritage has therefore worked with the architect John Burrell to show how this monumental public building, once thronged with people, can have a more public use again. SAVE invites public debate on the future of the Custom House. Re-connecting The City to the River Thames The Custom House is less than 200 metres from Leadenhall Market and the Lloyds Building and the Gherkin just beyond where high-rise buildings crowd out the sky. Who among the tens of thousands of City workers emerging from their offices in search of air and light make the short journey to the river? For decades it has been made virtually impossible by the traffic fumed canyon that is Lower Thames Street. Yet recently for several weeks we have seen a London free of traffic where people can move on foot or bike without being overwhelmed by noxious fumes. -

Shoreditch E1 01–02 the Building

168 SHOREDITCH HIGH ST. SHOREDITCH E1 01–02 THE BUILDING 168 Shoreditch High Street offers up to 35,819 sq ft of contemporary workspace over six floors in Shoreditch’s most sought after location. High quality architectural materials are used throughout, including linear handmade bricks and black powder coated windows. Whilst the top two floors use curtain walling with black vertical fins – altogether a dramatic first impression for visitors on arrival. The interior is designed with dynamic businesses in mind – providing a stunning, light environment in which to work and create. STELLAR WORK SPACE 03–04 SHOREDITCH Shoreditch is still the undisputed home of the creative and tech industries – but has in recent years attracted other business sectors who crave the vibrant local environment, diverse amenity offering and entrepreneurial spirit. ORIGINALS ARTISTS VISIONARIES HOXTON Crondall St. d. Rd R st nd . Ea la s ng Ki xton St Ho . 05–06 SHOREDITCH Columbia Rd St Hoxton Sq. Rd 6 y d. R Pitfield ckne t s Ha Ea k Pl. Brunswic City 5 R d. 5 Cu St. d r Ol ta Calv et Ave i . 4 n Rivington Rd. Rd WALK TIMES . Arnold Circus. 3 11 OLD ST. 8 8 4 3 6 5 12 SHOREDITCH HIGH ST. STATION 7 MINS Shor 03 9 Gr 168 edit Leonard St. eat 1 10 1 E New Yard Inn. ch High . aste 4 6 7 11 2 Rd 2 10 h St. OLD SPITALFIELD MARKET . 2 churc een t rn 3 Red 4 MINS . 1 9 S St 9 07 8 . -

Gtech Surveys Limited

GTech Surveys Limited Baseline Docklands Light Railway (DLR) Radio Signal Survey & DLR Radio Reception Impact Assessment 1 Bradfield Road CHANGE HISTORY Issue Date Details of Changes 0.0 16/04/2021 Working draft 0.1 11/05/2021 First draft issue Author: G Phillips Reviewer: O Lloyd Issue: 0.1 ©GTech Surveys Limited 2021 Contents Page GTech Surveys Limited Executive Summary 1 - Introduction 4 2 - The Mechanisms of Interference Radio Networks 7 3 - The Existing DLR Radio System 10 4 - Survey Methodology 14 5 - Baseline Reception Conditions 16 6 - Predicted Impacts and Effects 18 7 - Mitigation Measures 19 8 - Conclusions 20 Appendix 21 DLR Remote Radio Sites DLR Remote Radio Site Grid Reference DLR Remote Radio Sites Schematic References Mapping Data Issue: 0.1 1 ©GTech Surveys Limited 2021 GTech Surveys Limited GTech Surveys Limited is a Midlands based broadcast and telecommunications consultancy conducting projects throughout the entire UK. We undertake mobile phone network, television and radio reception surveys (pre- and post- construction signal surveys), conduct broadcast interference and reception investigations, and support telecommunications planning work for wind energy developers, construction companies, architects, broadcasters and Local Planning Authorities. In addition to radio interference modelling services and television reception surveys, we produce EIA and ES Telecommunications Chapters (also known as an 'Electronic Interference Chapter'); satisfying the requirements of Part 5, Regulation 18 (Parts 5a and 5b) of The Town and Country Planning EIA Regulations 2017. We peer review ES and EIA work, liaising with telecommunications providers (Arqiva, BT etc.) and advise developers with respect to associated Section 106 (Town and Country Planning Act 1990) and Section 75 (Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997) agreements. -

History and the Future

HISTORY AND THE FUTURE The conversion of these Victorian warehouses All around you lies a warren of old, cobbled streets, When the Pool of London teemed with tall ships, has given the capital some of its most dramatic where shipbrokers and chandleries have given way they unloaded coffee, cocoa beans, coconut living spaces. These are domestic interiors on an to art galleries, restaurants and fashionable shops. matting, oils, spices and dried fruit - then lowered industrial scale, where the raw simplicity of the Metropolitan Wharf is one of the last Docklands them onto horse-drawn carts which clattered off architecture creates the perfect backdrop to the warehouses to be restored, in a four year around London and beyond. best in modern design. programme of work that has retained as much of the historic fabric as possible. On the river side, enjoy big skies and ever- changing light as pleasure boats and workboats Metropolitan Wharf is steeped in history. It is come and go. On the city side, these buildings made up of four warehouse buildings, constructed provide a fresh perspective on the London skyline, between 1862 and 1898. The exterior features with spectacular views both day and night. some of Docklands’ fi nest jibs, cranes and hoists. WELCOME TO METROPOLITAN WHARF Walk into Metropolitan Wharf today and you will start to appreciate the exciting mix of past and present which characterises the entire development. The original brickwork, ceilings and cast iron columns look down on modern art and a striking copper reception desk - designed to patinate with age. Bottega Wapping - a busy cafe, delicatessen, As you look around you will see this is a multi-use development, wine bar and destination restaurant, where an urban village within a building. -

Tower of London World Heritage Site Management Plan

Tower of London World Heritage Site Management Plan Published by Historic Royal Palaces © Historic Royal Palaces 2007 Historic Royal Palaces Hampton Court Palace Surrey KT8 9AU June 2007 Foreword By David Lammy MP Minister for Culture I am delighted to support this Management Plan for the Tower of London World Heritage Site. The Tower of London, founded by William the Conqueror in 1066-7, is one of the world’s most famous fortresses, and Britain’s most visited heritage site. It was built to protect and control the city and the White Tower survives largely intact from the Norman period. Architecture of almost all styles that have since flourished in England may be found within the walls. The Tower has been a fortress, a palace and a prison, and has housed the Royal Mint, the Public Records and the Royal Observatory. It was for centuries the arsenal for small arms, the predecessor of the present Royal Armouries, and has from early times guarded the Crown Jewels. Today the Tower is the key to British history for visitors who come every year from all over the world to relive the past and to enjoy the pageantry of the present. It is deservedly a World Heritage Site. The Government is accountable to UNESCO and the wider international community for the future conservation and presentation of the Tower. It is a responsibility we take seriously. The purpose of the Plan is to provide an agreed framework for long-term decision-making on the conservation and improvement of the Tower and sustaining its outstanding universal value. -

Number 12 the Utterly Broken Britain Issue

Five Dials Number 12 The Utterly Broken Britain Issue Featuring interviews with 42 citizens on the state of the nation Plus Tories in East London Death Duels Circumcision Typewriters Intergenerational Love Affairs and Dangerous Snakes CONTRIBUTORS Sophia auguSta is a member of pLATS, an illustration collective she co-founded in 2005. AlaiN de bottoN is the author, most recently, of The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work. pauL daviS is an illustrator and artist. His work has been shown in Osaka, Bangkok, Birmingham, New York and many other cities. CoLiN Elford works as a Forest Ranger on the Dorset/Wiltshire border. He is the author of Practical Woodland Stalking and, most recently, A Year in the Woods: The Diary of a Forest Ranger. Jamie fewery conducted most of the interviews for our Broken Britain survey. His blog can be found at bottledandshelved.com. Jeremy Gavron is writer in residence at the Marie Curie hospice in Belsize Park, London. His most recent novel is An Acre of Barren Ground. daN hancox writes about music, politics and pop culture for the Guardian, New Statesman and Prospect. He spent two months following the 2008 US Presidential election, which turned into a book called My Fellow Americans. He has an uncanny habit of running into extremists on poorly lit street corners, from San Diego to Budapest. SimoN prosser is the publishing director of Hamish Hamilton. emiLy robertSoN’s illustration of a house adorns the UK hardcover edition of Lorrie Moore’s A Gate At The Stairs. She is a member of pLATS. JameS robertSoN is the author of The Testament of Gideon Mack, among others.