EJ-Nuclear-0210.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: WEAPONS of WAR Suggested Reading List

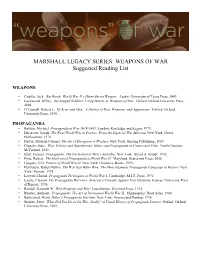

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: WEAPONS OF WAR Suggested Reading List WEAPONS • Couffer, Jack. Bat Bomb: World War II’s Other Secret Weapon. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992. • Lockwood, Jeffrey. Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. • O’Connell, Robert L. Of Arms and Men: A History of War, Weapons, and Aggression. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990. PROPAGANDA • Balfour, Michael. Propaganda in War 1939-1945. London: Routledge and Kegan, 1979. • Darracott, Joseph. The First World War in Posters: From the Imperial War Museum. New York: Dover Publications, 1974 • Dewar, Michael Colonel. The Art of Deception in Warfare. New York: Sterling Publishing, 1989. • Dipaolo, Marc. War, Politics and Superheroes: Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film. North Carolina: McFarland, 2011. • Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. • Fyne, Robert. The Hollywood Propaganda of World War II. Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2008. • Gregory, G.H. Posters of World War II. New York: Gramercy Books, 1993. • Hertzstein, Robert Edwin. The War that Hitler Won: The Most Infamous Propaganda Campaign in History. New York: Putnam, 1978. • Laswell, Harold. Propaganda Techniques in World War I. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1971. • Laurie, Clayton. The Propaganda Warriors: America’s Crusade Against Nazi Germany. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1996. • Rendell, Kenneth W. With Weapons and Wits. Lincolnshire: Overlord Press, 1992. • Rhodes, Anthony. Propaganda: The Art of Persuasion World War II. Minneapolis: Book Sales, 1988. • Rutherford, Ward. Hitler’s Propaganda Machine. New York: Grosset and Dunlop, 1978. • Stanley, Peter. What Did You Do in the War, Daddy? A Visual History of Propaganda Posters. -

The Making of an Atomic Bomb

(Image: Courtesy of United States Government, public domain.) INTRODUCTORY ESSAY "DESTROYER OF WORLDS": THE MAKING OF AN ATOMIC BOMB At 5:29 a.m. (MST), the world’s first atomic bomb detonated in the New Mexican desert, releasing a level of destructive power unknown in the existence of humanity. Emitting as much energy as 21,000 tons of TNT and creating a fireball that measured roughly 2,000 feet in diameter, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test, forever changed the history of the world. The road to Trinity may have begun before the start of World War II, but the war brought the creation of atomic weaponry to fruition. The harnessing of atomic energy may have come as a result of World War II, but it also helped bring the conflict to an end. How did humanity come to construct and wield such a devastating weapon? 1 | THE MANHATTAN PROJECT Models of Fat Man and Little Boy on display at the Bradbury Science Museum. (Image: Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.) WE WAITED UNTIL THE BLAST HAD PASSED, WALKED OUT OF THE SHELTER AND THEN IT WAS ENTIRELY SOLEMN. WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE THE SAME. A FEW PEOPLE LAUGHED, A FEW PEOPLE CRIED. MOST PEOPLE WERE SILENT. J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER EARLY NUCLEAR RESEARCH GERMAN DISCOVERY OF FISSION Achieving the monumental goal of splitting the nucleus The 1930s saw further development in the field. Hungarian- of an atom, known as nuclear fission, came through the German physicist Leo Szilard conceived the possibility of self- development of scientific discoveries that stretched over several sustaining nuclear fission reactions, or a nuclear chain reaction, centuries. -

Nuclear Deterrence in the Information Age?

SUMMER 2012 Vol. 6, No. 2 Commentary Our Brick Moon William H. Gerstenmaier Chasing Its Tail: Nuclear Deterrence in the Information Age? Stephen J. Cimbala Fiscal Fetters: The Economic Imperatives of National Security in a Time of Austerity Mark Duckenfield Summer 2012 Summer US Extended Deterrence: How Much Strategic Force Is Too Little? David J. Trachtenberg The Common Sense of Small Nuclear Arsenals James Wood Forsyth Jr. Forging an Indian Partnership Capt Craig H. Neuman II, USAF Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Mission Statement Commander, Air Education and Training Command Strategic Studies Quarterly (SSQ) is the senior United States Air Force– Gen Edward A. Rice Jr. sponsored journal fostering intellectual enrichment for national and Commander and President, Air University international security professionals. SSQ provides a forum for critically Lt Gen David S. Fadok examining, informing, and debating national and international security Director, Air Force Research Institute matters. Contributions to SSQ will explore strategic issues of current and Gen John A. Shaud, PhD, USAF, Retired continuing interest to the US Air Force, the larger defense community, and our international partners. Editorial Staff Col W. Michael Guillot, USAF, Retired, Editor CAPT Jerry L. Gantt, USNR, Retired, Content Editor Disclaimer Nedra O. Looney, Prepress Production Manager Betty R. Littlejohn, Editorial Assistant The views and opinions expressed or implied in the SSQ are those of the Sherry C. Terrell, Editorial Assistant authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, Air Education Editorial Advisors and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or depart- Gen John A. -

The Apocalypse Archive: American Literature and the Nuclear

THE APOCALYPSE ARCHIVE: AMERICAN LITERATURE AND THE NUCLEAR BOMB by Bradley J. Fest B. A. in English and Creative Writing, University of Arizona, Tucson, 2004 M. F. A. in Creative Writing, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Bradley J. Fest It was defended on 17 April 2013 and approved by Jonathan Arac, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of English Adam Lowenstein, PhD, Associate Professor of English and Film Studies Philip E. Smith, PhD, Associate Professor of English Terry Smith, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory Dissertation Director: Jonathan Arac, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of English ii Copyright © Bradley J. Fest 2013 iii THE APOCALYPSE ARCHIVE: AMERICAN LITERATURE AND THE NUCLEAR BOMB Bradley J. Fest, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation looks at global nuclear war as a trope that can be traced throughout twentieth century American literature. I argue that despite the non-event of nuclear exchange during the Cold War, the nuclear referent continues to shape American literary expression. Since the early 1990s the nuclear referent has dispersed into a multiplicity of disaster scenarios, producing a “second nuclear age.” If the atomic bomb once introduced the hypothesis “of a total and remainderless destruction of the archive,” today literature’s staged anticipation of catastrophe has become inseparable from the realities of global risk. -

A Selected Bibliography of Publications By, and About, J

A Selected Bibliography of Publications by, and about, J. Robert Oppenheimer Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 17 March 2021 Version 1.47 Title word cross-reference $1 [Duf46]. $12.95 [Edg91]. $13.50 [Tho03]. $14.00 [Hug07]. $15.95 [Hen81]. $16.00 [RS06]. $16.95 [RS06]. $17.50 [Hen81]. $2.50 [Opp28g]. $20.00 [Hen81, Jor80]. $24.95 [Fra01]. $25.00 [Ger06]. $26.95 [Wol05]. $27.95 [Ger06]. $29.95 [Goo09]. $30.00 [Kev03, Kle07]. $32.50 [Edg91]. $35 [Wol05]. $35.00 [Bed06]. $37.50 [Hug09, Pol07, Dys13]. $39.50 [Edg91]. $39.95 [Bad95]. $8.95 [Edg91]. α [Opp27a, Rut27]. γ [LO34]. -particles [Opp27a]. -rays [Rut27]. -Teilchen [Opp27a]. 0-226-79845-3 [Guy07, Hug09]. 0-8014-8661-0 [Tho03]. 0-8047-1713-3 [Edg91]. 0-8047-1714-1 [Edg91]. 0-8047-1721-4 [Edg91]. 0-8047-1722-2 [Edg91]. 0-9672617-3-2 [Bro06, Hug07]. 1 [Opp57f]. 109 [Con05, Mur05, Nas07, Sap05a, Wol05, Kru07]. 112 [FW07]. 1 2 14.99/$25.00 [Ber04a]. 16 [GHK+96]. 1890-1960 [McG02]. 1911 [Meh75]. 1945 [GHK+96, Gow81, Haw61, Bad95, Gol95a, Hew66, She82, HBP94]. 1945-47 [Hew66]. 1950 [Ano50]. 1954 [Ano01b, GM54, SZC54]. 1960s [Sch08a]. 1963 [Kuh63]. 1967 [Bet67a, Bet97, Pun67, RB67]. 1976 [Sag79a, Sag79b]. 1981 [Ano81]. 20 [Goe88]. 2005 [Dre07]. 20th [Opp65a, Anoxx, Kai02]. -

Assuring South Korea and Japan As the Role and Number of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Are Reduced

Assuring South Korea and Japan as the Role and Number of U.S. Nuclear Weapons are Reduced Michael H. Keifer, Project Manager Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Defense Threat Reduction Agency Prepared by Kurt Guthe Thomas Scheber National Institute for Public Policy January 2011 The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. This report is approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Report Number ASCO 2011 003 Contract Number MIPR 10-2621M The mission of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) is to safeguard America and its allies from weapons of mass destruction (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high explosives) by providing capabilities to reduce, eliminate, and counter the threat, and mitigate its effects. The Advanced Systems and Concepts Office (ASCO) supports this mission by providing long-term rolling horizon perspectives to help DTRA leadership identify, plan, and persuasively communicate what is needed in the near term to achieve the longer-term goals inherent in the agency’s mission. ASCO also emphasizes the identification, integration, and further development of leading strategic thinking and analysis on the most intractable problems related to combating weapons of mass destruction. For further information on this project, or on ASCO’s broader research program, please contact: Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office 8725 John J. Kingman Road Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060-6201 [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction...................................................................................................................... -

Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons

VERSION: Charles P. Blair, “Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons,” in Gary Ackerman and Jeremy Tamsett, eds., Jihadists and Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Growing Threat (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 193-238. c h a p t e r 8 Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons Charles P. Blair CONTENTS Introduction 193 Improvised Nuclear Devices (INDs) 195 Fissile Materials 198 Weapons-Grade Uranium and Plutonium 199 Likely IND Construction 203 External Procurement of Intact Nuclear Weapons 204 State Acquisition of an Intact Nuclear Weapon 204 Nuclear Black Market 212 Incidents of Jihadist Interest in Nuclear Weapons and Weapons-Grade Nuclear Materials 213 Al-Qa‘ida 213 Russia’s Chechen-Led Jihadists 214 Nuclear-Related Threats and Attacks in India and Pakistan 215 Overall Likelihood of Jihadists Obtaining Nuclear Capability 215 Notes 216 Appendix: Toward a Nuclear Weapon: Principles of Nuclear Energy 232 Discovery of Radioactive Materials 232 Divisibility of the Atom 232 Atomic Nucleus 233 Discovery of Neutrons: A Pathway to the Nucleus 233 Fission 234 Chain Reactions 235 Notes 236 INTRODUCTION On December 1, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet made a hastily planned, clandestine trip to Pakistan. Tenet arrived in Islamabad deeply shaken by the news that less than three months earlier—just weeks before the attacks of September 11, 2001—al-Qa‘ida and Taliban leaders had met with two former Pakistani nuclear weapon scientists in a joint quest to acquire nuclear weapons. Captured documents the scientists abandoned as 193 AU6964.indb 193 12/16/08 5:44:39 PM 194 Charles P. Blair they fled Kabul from advancing anti-Taliban forces were evidence, in the minds of top U.S. -

―Basically a True Story:‖ the Beginning Or the End, Fat Man and Little Boy, and American Remembrance of the Atomic Bomb

―Basically a True Story:‖ The Beginning or the End, Fat Man and Little Boy, and American Remembrance of the Atomic Bomb By Theresa Lynn Verstreater B.A. in History, December 2008, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts January 31, 2015 Thesis directed by Charles Thomas Long Assistant Professor of History Abstract of Thesis ―Basically a True Story:‖ The Beginning or the End, Fat Man and Little Boy, and American Remembrance of the Atomic Bomb The impact of film as a vehicle for dissolution of information should not be discounted because it allows the viewer to experience the story alongside the characters and makes historical moments more relatable when presented through the modern medium. This, however, can be a double-edged sword as it relates to the creation of collective memory. This thesis examines two films from different eras of the post-atomic world, The Beginning or the End (1947) and Fat Man and Little Boy (1989), to discover their strengths and weaknesses both cinematically and as historical films. Studied in this way, the films reveal a leniency toward what professional historians might consider to be historical ―truth‖ while emphasizing moral ambiguity about the bomb and the complex relationships among the men and women responsible for its creation. While neither film boasts outstanding filmmaking, each attempts to educate the viewer while maintaining entertainment value through romantic subplots and impressive special effects. -

Un Dioparama Du Regroupement Pour La Surveillance Du Nucléaire

l’Uranium un dioparama du Regroupement pour la surveillance du nucléaire (Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility) presenté par Gordon Edwards, Ph.D., président du RSN, aux commissaires du BAPE, le 17 novembre, 2014 Regroupement pour la surveillance du nucléaire www.ccnr.org/index_f.html PART 1 Uses for Uranium 1. Nuclear Weapons 2. Fuel for Nuclear Reactors A Model of the Every atom has a Uranium Atom tiny “nucleus” at the centre, with electrons in orbit around it. Uranium is special. It is the key element behind all nuclear technology, whether military or civilian. Photo: Robert Del Tredici A Monument to the Splitting of the Atom Splitting of the Atom When the uranium nucleus is “split” enormous energy is released. And the broken pieces of uranium atoms are extremely radioactive. iPhoto: Robert Del Tredici Canadian Uranium for Bombs 1941-1965 The Quebec Accord CANADA – USA - UK Prime Quebec City President Prime Minister 1943 of the U.S.A. Minister of Canada of Britain Quebec Agreement Uranium from Canada to be used in WWII Atomic Bomb Project Fat Man – made from plutonium (a uranium derivative) Fat Man and Little Boy Little Boy – made from Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) Models of the two Atomic Bombs dropped on Japan in 1945 iPhoto: Robert Del Tredici Destruction of the City of Hiroshima caused by Little Boy, August 6, 1945 The Yellowcake Road (Canada) Yellowcake Road All uranium goes to Port Hope on Lake Ontario for Map by G. Edwards conversion to uranium hexafluoride or uranium dioxide & Robert Del Tredici Uses of Uranium UnGl 1945, all Canadian uranium was sold to the US military for Bombs. -

Nuclear Scholars Initiative a Collection of Papers from the 2013 Nuclear Scholars Initiative

Nuclear Scholars Initiative A Collection of Papers from the 2013 Nuclear Scholars Initiative EDITOR Sarah Weiner JANUARY 2014 Nuclear Scholars Initiative A Collection of Papers from the 2013 Nuclear Scholars Initiative EDITOR Sarah Weiner AUTHORS Isabelle Anstey David K. Lartonoix Lee Aversano Adam Mount Jessica Bufford Mira Rapp-Hooper Nilsu Goren Alicia L. Swift Jana Honkova David Thomas Graham W. Jenkins Timothy J. Westmyer Phyllis Ko Craig J. Wiener Rizwan Ladha Lauren Wilson Jarret M. Lafl eur January 2014 ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars are developing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofi t or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affi liated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to fi nding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. -

Risk Criticism: Precautionary Reading in an Age of Environmental

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages RISK CRITICISM Revised Pages Revised Pages Risk Criticism PRECAUTIONARY READING IN AN AGE OF ENVIRONMENTAL UNCERTAINTY Molly Wallace UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Molly Wallace All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Wallace, Molly, author. Title: Risk criticism : precautionary reading in an age of environmental uncertainty / Molly Wallace. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015038637 | ISBN 9780472073023 (hardback) | ISBN 9780472053025 (paperback) | ISBN 9780472121694 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Ecocriticism. | Criticism. | Risk in literature. | Environmental risk assessment. | Risk-taking (Psychology) Classification: LCC PN98.E36 W35 2016 | DDC 809/.93355— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015038637 Revised Pages For my family Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This book has been a number of years in the writing, and I am deeply grate- ful for the support and encouragement that I have received along the way. -

Making the Bomb by John Lamperti

November, 2012 Thoughts on Making the Bomb by John Lamperti I recently finished reading Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird’s monumental American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.1 It's an admirable book, although I think the title might better have been American Faust. (No less than Freeman Dyson said Oppenheimer made a "Faustian bargain."2) There have been many books about Oppenheimer and the atomic bomb project in general; I've read some but not all of them. This one seems to be definitive. Everything we need to know is there – and it's a fascinating read. Two things struck me especially, and neither was directly about Oppenheimer. One was the ideological rigidity, and the blindness, of the crowd of Army and FBI "security" operatives who dogged Oppenheimer and the whole Manhattan Project from the beginning. To a man (no women are mentioned) they were obsessed with the pre-war leftist politics of many of the scientists, which they found highly suspicious and probably indicative of disloyalty. But while these agents were hounding leftists and "premature anti-fascists" (as supporters of the Spanish Republic were called) at Los Alamos and elsewhere and finding little or nothing, real spies were sending real scientific information to the USSR under their noses, apparently unsuspected. If the "security" people, especially Lt. Col. Boris Pash of Army Counter– Intelligence, had been given free rein, Oppenheimer and many others (but not the actual spies!) would have been banished from the Project and the "Trinity" test, as well as the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, might never have happened.