Oscar Shumsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAN MRÁČEK, Violin

JAN MRÁČEK, violin Czech violinist Jan Mráček was born in 1991 in Pilsen and began studying violin at the age of 5, most recently under the guidance of the former Vienna Symphony concert master Jan Pospíchal. As a teenager he enjoyed his first successes, winning numerous competitions, participating in the master classes of Maestro Václav Hudeček - the beginning of a long and fruitful association. He was the youngest Laureate of the Prague Spring International Festival competition in 2010, and in 2011 was the youngest soloist in the history of the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra. In 2014 he took first prize at Vienna’s Fritz Kreisler International Violin Competition at the Vienna Konzerthaus. He has performed as soloist with the Kuopio Symphony Orchestra and Romanian Radio Symphony, both under Sascha Goetzel, Lappeenranta City Orchestra (Finland), Czech National Symphony Orchestra, Prague Symphony Orchestra (FOK), Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra and almost all Czech regional orchestras. Jan Mráček had the honour of being invited by Maestro Jiří Bělohlávek to guest lead the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in their three concert residency at Vienna’s Musikverein, and the European Youth Orchestra under Gianandrea Noseda and Xian Zhang on their 2015 summer tour. He is a member of the Lobkowicz Piano Trio, which took first prize and the audience prize at the International Johannes Brahms Competition in Pörtschach (Austria) in 2014. His acclaimed recording of the Dvořák violin concerto and other works by the Czech composer under James Judd with the Czech National Symphony was released on the Onyx label, and most recently he recorded works of Milan Mihajlovic with Howard Griffiths and the Brandenburg State Symphony for the CPO label. -

2014-2015 Philharmonia No. 5

Lynn Philharmonia No. 5 2014-2015 Season Lynn Philharmonia Roster VIOLIN CELLO FRENCH HORN JunHeng Chen Patricia Cova Mileidy Gonzalez Erin David Akmal Irmatov Mateusz Jagiello Franz Felkl Trace Johnson Shaun Murray Wynton Grant Yuliya Kim Raul Rodriguez Herongia Han Elizabeth Lee Clinton Soisson Xiaonan Huang Clarissa Vieira Hugo Valverde Villalobos Julia Jakkel Shuyu Yao Nora Lastre Jennifer Lee DOUBLE BASS Lilliana Marrero August Berger TRUMPET Cassidy Moore Evan Musgrave Zachary Brown Yaroslava Poletaeva Jordan Nashman Ricardo Chinchilla Olesya Rusina Amy Nickler Marianela Cordoba Vijeta Sathyaraj Isac Ryu Kevin Karabell Yalyen Savignon Mark Poljak Kristen Seto FLUTE Natalie Smith Delcho Tenev Mark Huskey Yordan Tenev Jihee Kim TROMBONE Marija Trajkovska Alla Sorokoletova Mariana Cisneros Anna Tsukervanik Anastasia Tonina Zongxi Li Mozhu Yan Derek Mitchell OBOE Emily Nichols VIOLA Paul Chinen Patricio Pinto Felicia Besan Asako Furuoya Jordan Robison Brenton Caldwell Kelsey Maiorano Hao Chang Trevor Mansell TUBA Sean Colbert Joseph Guimaraes Zefeng Fang CLARINET Josue Jimenez Morales Roberto Henriquez Anna Brumbaugh Nicole Kukieza Jesse Yukimura Jacqueline Gillette Alberto Zilberstein Amalia Wyrick-Flax PERCUSSION Kirk Etheridge BASSOON Isaac Fernandez Hernandez Hyunwook Bae Parker Lee Sebastian Castellanos Jesse Monkman Joshua Luty Ruth Santos 2 Lynn Philharmonia No. 5 Guillermo Figueroa, music director and conductor Saturday, March 21 – 7:30 p.m. Sunday, March 22 – 4 p.m. Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center In Memoriam (World Premiere) Marshall Turkin Der Geretette Alberich, Christopher Rouse Fantasy for solo percussion and orchestra (b. 1949) Edward Atkatz, percussion INTERMISSION Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major “Eroica”, Op. 55 Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro con brio (1770-1827) Marcia funebre: Adagio assai in C minor Scherzo: Allegro vivace Finale: Allegro molto Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. -

2015-2016 the Three Violin Sonatas by Béla Bartók: Guillermo Figueroa

The Three Violin Sonatas by Béla Bartók: Guillermo Figueroa, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano 2015-2016 Season The Three Violin Sonatas by Béla Bartók: Guillermo Figueroa, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Thursday, January 14, 2016 7:30 p.m. Count and Countess de Hoernle International Center Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall Béla Bartók (1881-1945) Sonata No. 2 for violin and piano, Sz. 76 (1922) Molto moderato Allegretto Poco piu vivo (the two movements are played without pause) Sonata for Solo Violin, Sz. 117 (1944) Tempo di ciaccona Fuga Melodia Presto Intermission Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano, Sz. 75 (1921) Allegro appassionato Adagio Allegro Allegro molto Biographies Guillermo Figueroa Renowned both as conductor and violinist, Guillermo Figueroa is Music Director of the Music in the Mountains Festival in Durango, Colorado and Music Director and Conductor of the Lynn Philharmonia. He was also the Founder and Artistic Director of The Figueroa Music and Arts Project in Albuquerque. Additionally, he was the Music Director of both the New Mexico Symphony and the Puerto Rico Symphony. With this last orchestra he performed to critical acclaim at Carnegie Hall in 2003, the Kennedy Center in 2004 and Spain in 2005. His international appearances as a Guest Conductor include the Toronto Symphony, Iceland Symphony, the Baltic Philharmonic in Poland, Orquesta del Teatro Argentino in La Plata (Buenos Aires), Xalapa (Mexico), the Orquesta de Cordoba in Spain and the Orquesta Sinfonica de Chile. In the US he has appeared with the symphony orchestras of Detroit, New Jersey, Memphis, Phoenix, Colorado, Berkeley, Tucson, Santa Fe, Toledo, Fairfax, San Jose, Juilliard Orchestra and the New York City Ballet at Lincoln Center. -

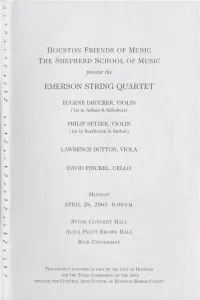

Emerson String Quartet

HOUSTON FRIENDS OF MUSIC THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC present the EMERSON STRING QUARTET EUGENE DRUCKER, VIOLIN (1st in Aitken & Schubert) PHILIP SETZER, VIOLIN (1st in Beethoven & Barber) .. LAWRENCE DUTTON, VIOLA DAVID FINCKEL, CELLO MONDAY -,. APRIL 28, 2003 8:00 P.M. STUDE CONCERT HALL ALICE PRATT BROWN HALL RICE UNIVERSITY THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED IN PART BY THE CITY OF HOUSTON AND TIIE T EXAS COMMISSION ON THE ARTS THROUGH THE CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL OF HOUSTON/HARRIS COUNTY. EMERSON STRING QUARTET -PROGRAM- LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro HUGH AITKEN (b.1924) Laura Goes to India (1998) SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) A . Adagio for String Quartet, Op. 11 (1936) -INTERMISSION- FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Quartet in D Minor, D. 810, "Death and the Maiden" (1824) Allegro Andante con moto Scherzo: Allegro molto Presto -.. The Emerson String Quartet appears by arrangement with IMC Artists and records exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. www.emersonquartet.com LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) ·.1 Beethoven wrote the Opus 18 Quartets during his first years in Vienna. He had arrived from Germany in 1792 by permission of the Elector of Bonn, shortly before his twenty-second birthday, in high spirits and carrying with him introductions to some of the most prominent members of music-loving Viennese nobility, who welcomed him into their substantial musical lives. At the end of his first four years in Vienna he had established himself as a pianist of major importance and a composer of the utmost promise; he had published, among other things, a set of three Piano Trios, Op.l, three Trios for Strings, Op. -

The Glenn Dicterow Collection

New York Philharmonic Presents: THE GLENN DICTEROW COLLECTION New York Philharmonic Presents: LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918-1990) ALBUM 3 (DOWNLOAD ONLY) 85:51 THE GLENN DICTEROW Serenade (after Plato’s “Symposium”) for Violin, String Orchestra, Harp, SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953) and Percussion 33:40 Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor, COLLECTION 2 Phaedrus: Pausanias Op. 63 25:18 (Lento – Allegro marcato) 7:35 1 Allegro moderato 0:20 3 Aristophanes (Allegretto) 4:42 2 Andante assai – Allegretto – Tempo I 8:56 4 Erixymachus (Presto) 1:30 3 Allegro ben marcato 6:02 5 ALBUM 1 (CD AND DOWNLOAD) 76:12 Agathon (Adagio) 8:00 Zubin Mehta, conductor 6 Socrates: Alcibiades (Molto tenuto – June 15, 1985, Beethovenhalle, Bonn, Germany Allegro molto vivace – Presto vivace) 11:53 MAX BRUCH (1838-1920) 5 Moderato nobile 8:54 Leonard Bernstein, conductor KAROL SZYMANOWSKI (1882-1937) Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, 6 Romance 8:09 August 14, 1986, Blossom Music Center, Ohio 4 Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 35 24:16 Op. 26 26:11 7 Finale: Allegro assai vivace 7:12 Kurt Masur, conductor 1 Prelude: Allegro moderato and Adagio 18:38 David Robertson, conductor SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) January 8, 9, 10, 13, 2004, Avery Fisher Hall 2 Finale: Allegro energico 7:33 May 22, 23, 24, 2008, Avery Fisher Hall Lorin Maazel, conductor Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 14 24:02 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) March 9,13,14, 2009, Avery Fisher Hall JOHN WILLIAMS (B. 1932) 7 Allegro 11:31 Concerto No. 1 in A minor for 8 Theme from Schindler’s List 3:58 8 Andante 8:28 Violin and Orchestra, Op. -

Emerson String Quartet

Emerson String Quartet The Emerson String Quartet has maintained its stature as one of the world’s premier chamber music ensembles for more than four decades. The quartet has made more than 30 acclaimed recordings, and has been honored with nine Grammys® (including two for Best Classical Album), three Gramophone Awards, the Avery Fisher Prize, and Musical America’s “Ensemble of the Year”. The Emerson frequently collaborates with some of today’s most esteemed composers to premiere new works, keeping the string quartet art form alive and relevant. They have partnered in performance with stellar soloists including Reneé Fleming, Barbara Hannigan, Evgeny Kissin, Emanuel Ax and Yefim Bronfman, to name a few. During the 2018-2019 season the Emerson continues to perform as the quartet in residence at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. for its 40th season and returns to perform with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. The group’s North American appearances include a performance at New York’s Alice Tully Hall, and appears around North America that include the Library of Congress in Washington DC, Denver, Vancouver, Seattle, Houston, Indianapolis, Detroit, the Yale School of Music and University of Georgia, among others. The quartet also embarks on two European tours, performing in major venues in the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy and Spain. During the summer of 2019, the Emerson will perform at Tanglewood, Ravinia, and the Aspen Music Festivals. Other North American highlights include subsequent performances of Shostakovich and The Black Monk: A Russian Fantasy, the new theatrical production co-created by the acclaimed theater director James Glossman and the Quartet’s violinist, Philip Setzer. -

Tracing Curtis Traditions Curtis’S Rich Heritage Has Deeper Roots Than You May Realize

TRACING CURTIS TRADITIONS CURTIS’S RICH HERITAGE HAS DEEPER ROOTS THAN YOU MAY REALIZE BY MATTHEW BARKER Here’s a game for a lazy afternoon: Pick your favorite Curtis faculty member and count the connections back to 18th- and 19th-century masters. it’s fun, easy, and kind of amazing. Start with the violin. Current faculty members Aaron rosand, Joseph Silverstein, Michael tree, and Shmuel Ashkenasi all studied with efrem Zimbalist, Curtis’s director from 1941 to 1968. Go back just one generation and you’ll find that Zimbalist was a pupil of famed pedagogue Leopold Auer, the dedicatee of the tchaikovsky Leopold Auer Violin Concerto. Auer himself served on the Curtis faculty for two years, from 1928 to 1930. His pupils, at Curtis and elsewhere, also included Mischa elman, Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, toscha Seidel, and Oscar Shumsky. Also among current faculty members, ida Kavafian was a Shumsky student and Arnold Steinhardt Konstantin Mostras Oscar Shumsky (’36) Efrem Zimbalist Ivan Galamian Ida Kavafian Aaron Rosand (’48) Joseph Silverstein (’50) Michael Tree (Violin ’55) Shmuel Ashkenasi (’63) Arnold Steinhardt (’59) Yumi Ninomiya Scott (’67) Jaime Laredo (’59) Pamela Frank (’89) More Online Are you a part of this family tree? Let us PHOTOS: BETTMAN/CORBIS (BEETHOVEN, CZERNY, LESCHETIZKY, SCHNABEL); JEAN E. BRUBAKER (ROSAND, know where your branch fits in. Post a SOLZHENITSYN); PETE CHECCHIA (ASHKENASI, C. FRANK, KAVAFIAN, MCDONALD, SILVERSTEIN); JOYCE CREAMER/ comment on the Curtis Facebook page at CURTIS ARCHIVES (HORSZOWSKI); DAVID DEBALKO (TREE); DOROTHEA VON HAEFTEN (STEINHARDT); www.facebook.com/CurtisInstitute. L.C. KELLEY (P. FRANK), PETER SCHAAF (GALAMIAN); STEVE J. -

Lydia Tang Thesis.Pdf

THE MULTI-FACETED ARTISTRY OF VIOLIST EMANUEL VARDI BY LYDIA M. TANG THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolf Haken, Chair Associate Professor Katherine Syer, Director of Research Associate Professor Scott Schwartz Professor Stephen Taylor Clinical Assistant Professor Elizabeth Freivogel Abstract As a pioneer viola virtuoso of the 20th century, Emanuel “Manny” Vardi (c. 1915-2011) is most widely recognized as the first violist to record all of Paganini’s Caprices. As a passionate advocate for the viola as a solo instrument, Vardi premiered and championed now-standard repertoire, elevated the technique of violists by his virtuosic example, and inspired composers to write more demanding new repertoire for the instrument. However, the details of his long and diverse career have never to date been explored in depth or in a comprehensive manner. This thesis presents the first full biographical narrative of Vardi’s life: highlighting his work with the NBC Symphony under Arturo Toscanini, his activities as a soloist for the United States Navy Band during World War II, his compositional output, visual artwork, an analysis of his playing and teaching techniques, as well as his performing and recording legacies in classical, jazz, and popular music. Appendices include a chronology of his life, discography, lists of compositions written by and for Vardi, registered copyrights, and a list of interviews conducted by the author with family members, former students, and colleagues. -

Maryland State Music Teachers Association from the President…

Maryland State Music Teachers Association Affiliated with Music Teachers National Association www.msmta.org A bi-monthly publication of the Maryland State Music Teachers Association December 2012 MSMTA STATE CoNFereNCe “Celebrating Musical Diversity” SATURDAY aNd sUNDAY JaNUarY 12 & 13, 2013 RegistRation FoRm and details begin on page 2 From the President… News From the Board I wish all of you a happy holiday Fourteen Board members attended the meeting on Monday, season! December 3, 2012. A few items were discussed which As you see in this newsletter, we resulted in the following: have a fantastic conference planned for you. Since this year’s MTNA • Donation plan for Sandy Relief effort was discussed conference is in California, many and devised. It was moved, seconded and passed of you may not be able to attend, (please see the detailed info in the newsletter). but we are hoping we can bring a smaller-scale but equally high quality conference to Maryland. • Concerto competition chair, Hyun Park, proposed So I hope you can rest up during the holidays and attend our dividing the junior division to the following: conference to be rejuvenated at the start of the new year. Junior I: up to 5th grade. You have also probably gotten my global e-mail about the board decision to contribute to the Superstorm Sandy Relief Fund, which MTNA has specifically set up for our Eastern Junior II: up to 8th grade. Division colleagues in need. Some are left without a home in which to teach, others have damaged instruments, plus many The rule for winners will remain the same: previous other causes of financial strain. -

Eric Shumsky

.1 Ii Shumsky has taught viola at the Karlsruhe Hochschule in Gennany and at Les The School of Music Arcs in the French Alps. He has broadcast for the BBC, Radio France, Sudwest presents the 13th program of the 1989-90 season Deutsche Rundfink, Salzburg Radio, and Spanish and Korean television. He is presently professor of viola at the University of Washington in Seattle. Lisa Bergman is a native of Seattle and a graduate of both the Juilliard School and the University of Washington. She made her Carnegie Recital Hall debut in 1983 and has perfonned with such artists a Julius Baker, Mami Nixon, Steven Staryk, Ranson Wilson, and saxophonist Fred Hemke. Her festival appearances Faculty Artist Recital include Banff, Aspen, Shawnigan and the newly founded Augustine's Artists in Anchorage, Alaska. She is much in demand as a lecturer on the arlofaccompanying. Her first recording, with violinist Linda Rosenthal, was recently released on the Topaz label. Ss) 11 Be, Upcoming Coneerts 0- 2.8 Eric Shumsky University Wind Eosemble &- Sympbonic Band; November 29,8:00 PM, Violist Meany'lbeater University Jazz Combo; November 30,8:00 PM, Brechemin Auditorium witli University Sympbony; December 1,8:00 PM, Meany Thearer University Madrigal Singers &- Collegium Musieum; December 2, 8:00 PM; December 3. 3:00 PM; Brechemin Auditorium Lisa Bergman Studio Jazz Ensemble; December 4, 8:00 PM, M~yThearer Pianist New Music by Young Composers; December 5.8:00 PM, Brechemin Auditorium [- . Fri;d~~M:si~~ -~;---.- . :;trultiuuts un:TJMEFRIENDS HtI!fY and Helen Balisky 101m IIld Gail Mensher Carl and Conine Berg Howald and Audrey Morrill The Boein Company Karea GGatieb Bleaken IQII fl Nelsoo Brec:hc:mm'Famifv FOundalicln KeDy IIld Margaret Booham Rose Marie NdllCll Wdlimland RlIlIiGetbenting lames and DcJma Brudvik lames 1. -

Download Booklet

8.111383 bk Primrose2_EU_8.111383 bk Primrose2_EU 13/10/11 17.52 Pagina 1 Pleyel, with the Lamoureux Orchestra under Sir Mozart’s E flat Quintet, K614, with William Carboni Moennig Jnr and had the use of the ‘Macdonald’ Strad vivid contrasts, reflecting the divergent characters of Thomas Beecham, was the crucial event in for the New Friends of Music at Town Hall. ‘New (later heard in the Amadeus Quartet, in the hands of Primrose’s partners. The Adagio, recorded with Albert ADD Primrose’s career (although subsequently he would Yorkers have rarely … heard such playing as the Peter Schidlof), with its fine tone and instantly Spalding’s regular accompanist André Benoist as a Great Violists • Primrose skate over the Tertis connection, because of their Primrose Quartet vouchsafed yesterday,’ reported The recognisable diagonal-figured back. At this stage filler for Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante, is a model of 8.111383 disagreements on viola tone and vibrato, as well as New York Times. In 1941 Primrose took a chance and Primrose still had a tenor-oriented sound and could collaboration, the gentlemanly Spalding the ideal size of the instrument). Primrose had always went solo, touring the United States with the tenor play in quite a lush style, employing much portamento. accommodating his lovely tone and phrasing to felt affection for the viola but Tertis’s huge, warm Richard Crooks. He recorded with Jascha Heifetz and Later he concentrated on dexterity: his playing Primrose’s. The Passacaglia is at once a performance tone showed him its potential. In the Green Room he Emanuel Feuermann, joined the reconstituted London remained colourful but his vibrato, always on the fast of higher pressure, with the competitive virtuosi told Tertis: ‘I am a disciple of yours from henceforth.’ String Quartet for occasional concerts, and in 1947 side for a violist, seemed more intense than ever, the Heifetz and Primrose matching precision and filigree By 1930 he was playing viola in the London String appeared in London and at the first Edinburgh tone more alto than tenor. -

Leon Levy BAM Digital Archive

BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Ndnly I llu~111 BAM BROOKLYN Rll hard W lhtllwrl ACADEMY OF MUSC F'tut<' o( Fujol,rru• Kr1t\l't' I ~l.lnl<·y Km·~t·l PATRONS 1981-82 J.tc.:k l.awrtnu• The Brooklyn Academy of MusiC as Ph yilt\ llnlhrcw>k l.t< hlc·n\lc'lll 1>wncd by the City of New York and llam"h Muwrll admanastered by the Brooklyn Alan• Hnlhrcw>k Platt Frt·drru:k W R ~rhmo nd Fnundtttton Academy of Musac. Inc The Brook· Ruc.:kmradow Foun,ldttnn lyn Academy of Musac gratefully ac· The Starr Foundt1tton knowledges the support of the Na Wilham Tnllt')' laona! Endowment for the Arts. The Mu.: hael TUl:h Fuundauon New York State Council on the Arts. Jnhn T Untlerwood Fnundatmn and the Department of Cultural Af Tht Vmmnnt Foundatum faars of the City of New York In ad Harold Wrat> Duanr Wtldrr dillon. the Board of Trustees washes Rohert \V \Vtl.-.on Found.11um to thank the followang foundatons. Sanfnrd I Zlmmt:rm.m corporahons and andavaduals who. thn>ugh thear leadership and sup· PRODl CFRS S500 S'l'l'l port, help make these programs Rnht"rt H Arnow possable :O.otl D Chn,mnn Tho Henry Goldner~ F~undatlon .\lr & \lr. Phthp )o"ur Harvey l.!chttn\ttln \.lr & Mrs Rt chard ,\.lrn\Cht•l INDIVIDUALS AND \lr & .\lr. ,\ldrttn Sc~dl FOUNDATIONS Dan ~ymnur Tht' 7cttl Foundat1nn LEAOERS III P S25,000 a nd above ASSOCIATE PROD! CERS Achelas Fnundaaon S250 S499 Bodman Founda110n Boolh Ferns Foundation Robert Davenport Louas Calder Foundation Mr & Mrs AI Krontek Edna McConnell Clark Foundation Naa Lefknwlt7 Robert Sterling Clark Foundation