Metapolis. Metaphysics and the City*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

Giorgio De Chirico E Venezia: 1924-1936

255 GIORGIO DE CHIRICO E VENEZIA: 1924-1936 Giorgia Chierici SOMMARIO: Parte I Giorgio de Chirico e la Biennale di Venezia 1) 1924: XIV Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia 2) 1927-1930: da «Comœdia» alla non partecipazione alla XVI Biennale 1928 e XVII Biennale 1930 3) 1932: XVIII Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte Parte II Giorgio de Chirico e le mostre organizzate all’estero dalla Biennale 4) 1933: New York e Vienna 5) 1935: Varsavia e Parigi 6) 1936: Budapest Tavola delle abbreviazioni: APICE: Archivi della Parola, dell’Immagine e della Comunicazione Editoriale, Milano Archivio della Fondazione: Archivio Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, Roma ASAC: Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee, Venezia CRDAV: Centro Ricerca e Documentazione Arti Visive, Roma Mart: Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Trento e Rovereto, Rovereto Nota alla lettura: In caso di errori di ortografa e battitura nei testi originali, si è preferito trascrivere fedelmente ogni documento. La maggior parte delle lettere e documenti sono trascritti solo in parte, ed è riportata la collocazione dove sono contenuti. Metafisica 2018 | n. 17/18 256 Giorgia Chierici Parte I – Giorgio de Chirico e la Biennale di Venezia 1) 1924: XIV Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia Nel 1924 Giorgio de Chirico partecipa per la prima volta alla Biennale di Venezia. In questo primo capitolo attraverso la lettura dei documenti si ricostruisce il rapporto dell’artista con la Manifesta- zione Internazionale d’Arte di Venezia: in particolare, de Chirico invia le due opere L’ottobrata e I duelli a morte, entrambe del 1924, dipinti a tempera grassa, parentesi pittorica che lascerà il posto al “ritorno all’olio” e a nuovi temi degli anni successivi. -

IOA 34-1A11-0209

ATLAS OF WORLD INTERIOR DESIGN ATLAS OF WORLD INTERIOR DESIGN Markus Sebastian Braun | Michelle Galindo (ed.) The Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographical information can be found on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de ISBN 978-3-03768-061-2 © 2011 by Braun Publishing AG www.braun-publishing.ch The work is copyright protected. Any use outside of the close boundaries of the copyright law, which has not been granted permission by the publisher, is unauthor-ized and liable for prosecution. This espe- cially applies to duplications, translations, microfilming, and any saving or processing in electronic systems. 1st edition 2011 Project coordination: Jennifer Kozak, Manuela Roth English text editing: Judith Vonberg Layout: Michelle Galindo Graphic concept: Michaela Prinz All of the information in this volume has been compiled to the best of the editors’ knowledge. It is based on the information provided to the publisher by the architects‘ and designers‘ offices and excludes any liability. The publisher assumes no responsibility for its accuracy or completeness as well as copyright discrepancies and refers to the specified sources (architects’ and designers’ offices). All rights to the IMPRINT photographs are property of the photographer (please refer to the picture). k k page 009 Architecture) | Architonic Lounge | Cologne | 88 k Karim Rashid| The Deutsche Rome | 180 Firouz Galdo / Officina del Disegno and Michele De Lucchi / aMDL | Zurich | 256 k Pia M. Schmid | Kaufleuten Festsaal -

Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin As Examples1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HISTORICAL URBAN FABRIC provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository UDC 711 Wang Haoyu, Li Zhenyu College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, China, Shanghai, Yangpu District, Siping Road 1239, 200092 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] COMPARISON STUDY OF TYPICAL HISTORICAL STREET SPACE BETWEEN CHINA AND GERMANY: FRIEDRICHSTRASSE IN BERLIN AND CENTRAL STREET IN HARBIN AS EXAMPLES1 Abstract: The article analyses the similarities and the differences of typical historical street space and urban fabric in China and Germany, taking Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin as examples. The analysis mainly starts from four aspects: geographical environment, developing history, urban space fabric and building style. The two cities have similar geographical latitudes but different climate. Both of the two cities have a long history of development. As historical streets, both of the two streets are the main shopping street in the two cities respectively. The Berlin one is a famous luxury-shopping street while the Harbin one is a famous shopping destination for both citizens and tourists. As for the urban fabric, both streets have fishbone-like spatial structure but with different densities; both streets are pedestrian-friendly but with different scales; both have courtyards space structure but in different forms. Friedrichstrasse was divided into two parts during the World War II and it was partly ruined. It was rebuilt in IBA in the 1980s and many architectural masterpieces were designed by such world-known architects like O.M. -

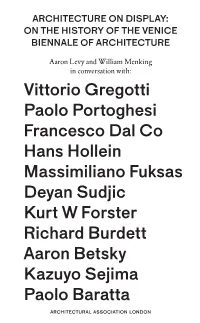

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

Abject Art, 33 Abraham, Karl, 82, 83, 246 Adorno, Theodor W., 92, 181

Index Page numbers in boldface indicate illustrations. Abject art, 33 Bachelor machines, 120, 151, 163, 173, 181, Abraham, Karl, 82, 83, 246 323, 334 Adorno, Theodor W., 92, 181 Baker, Josephine, 99 African art, 29, 31, 36, 159, 346n20 Ball, Hugo, 158, 166, 174, 176, 191, 286 Allen, Woody, 41 Balla, Giacomo, 132 Anthologie Dada, 158 Baroque art, 265–269 Apotropaic transformation, 260, 262, 263, Barthes, Roland, 238 268, 271, 272 Bataille, Georges, 4, 49, 204, 205, 238, Aragon, Louis, 209 242, 338 Arp, Hans, 158, 159, 186 Baudelaire, Charles, 12, 186 Art brut, 203–204 Bauhaus, 78, 110, 113, 114, 151, 199 Art Nouveau, 59, 81, 88–95, 98–99 Beehle, Hermann, 205, 206 Arts and crafts, 57, 58, 59, 60, 63, 65 Bellmer, Hans, 114, 181, 230–239, 231, Aurier, Albert, 44–45 234, 235, 237 Austro-Hungarian Empire, 56–57 Benjamin, Walter, 92–94, 99, 114, 168, 181, Authenticity, modernist critique of, 63–64, 185–186, 199, 202, 205 65, 67 Bergson, Henri-Louis, 134, 148 Berlin, 42, 223 Baargeld. See Grünwald, Alfred Bersani, Leo, 126 Baartman, Saartjie, 12 Bertelli, R. A., 128, 130 Index Biondo, Michael, 302 Castner, Louis, 157 Bleuler, Eugen, 194 Cellini, Benvenuto, 258 Bloch, Ernst, 94 Cézanne, Paul, 279 Boiffard, Jacques-André, 224, 225 Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Bois, Yve-Alain, 33 Lauves, 280 Bonn, University of, 156, 198, 209 Chagall, Marc, 158 Bosch, Hieronymus, 330 Charcot, Jean Martin, 194 Bourgeois aesthetics, 57, 65–70, 72, 75, Chasseguet-Smirgel, Janine, 87 92–94, 104 Chicago, 59 Bourke, John G., 84, 85 Children, art of, 193, 203 Brancusi, -

Doriana Massimiliano Fuksas

DORIANA MASSIMILIANO FUKSAS Lo Studio Fuksas, guidato da Massimiliano e Doriana Fuksas, è uno studio di architettura internazionale con sedi a Roma, Parigi, Shenzhen. Di origini lituane, Massimiliano Fuksas nasce a Roma nel 1944. Consegue la laurea in Architettura presso l’Università “La Sapienza” di Roma nel 1969. E’tra i principali protagonisti della scena architettonica contemporanea sin dagli anni ‘80. E’ stato Visiting Professor presso numerose università, tra le quali: la Columbia University di New York, l’École Spéciale d’Architecture di Parigi, the Akademie der Bildenden Künste di Vienna, the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste di Stoccarda.Dal 1998 al 2000 è stato Direttore della “VII Mostra Internazionale di Architettura di Venezia”: “Less Aesthetics, More Ethics”. Dal 2000 è autore della rubrica di architettura, fondata da Bruno Zevi, del settimanale italiano “L’Espresso”. Doriana Fuksas nasce a Roma dove consegue la laurea in Storia dell’Architettura Moderna e Contemporanea presso l’Università “La Sapienza” di Roma nel 1979. Laureata in Architettura all’ESA -ÉcoleSpéciale d’Architecture- di Parigi, Francia. Dal 1985 collabora con Massimiliano Fuksas e dal 1997 è responsabile di “Fuksas Design”. Ha ricevuto diversi premi e riconoscimentiinternazionali. Nel 2013 è stata insignita dell’onorificenza di “Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres de la République Française” e nel 2002 di “Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres de la République Française”. Studio Fuksas, led by Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas, is an international architectural practice with offices in Rome, Paris, Shenzhen. Of Lithuanian descent, Massimiliano Fuksas was born in Rome in 1944. He graduated in Architecture from the University of Rome “La Sapienza” in 1969. -

1968, Tendenza and Education in Aldo Rossi

1 Histories of PostWar Architecture 2 | 2018 | 1 Monument in Revolution: 1968, Tendenza and Education in Aldo Rossi Kenta Matsui PhD Candidate, The University of Tokyo (Japan), Department of Architecture, Graduate School of Engineering [email protected] MA Degree in History of Architecture at the Graduate school of the University of Tokyo. Research Fellowship for Young Scientists supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (2016-2018). His research focuses on the architectural theories of Aldo Rossi and other contemporary Italian architects in relation to the contexts of postwar Italy. ABSTRACT In the 1960’s, as Italian architectural schools faced student protests and forceful occupation attempts, Aldo Rossi tried to reform the schools through the idea of ‘tendency school’ shared with Carlo Aymonino, and to reconstruct architecture as discipline and theory. His theory has two aspects: urban analysis and architectural project. The former presents a dynamic conception of the temporal evolution of the city, as if echoing the restless social situation of the time; the latter centers on the logicality of architecture represented by monuments. This study explores the meaning of this dualism between urban analysis and architectural project as an intent for revolution, and in light of this, investigates the idea of ‘monument in revolution’. This study was supported by a research fund from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP16J05298). I would like to thank Bébio Amaro (Assistant Professor at Tianjin University, School of Architecture) for his aid in checking and revising the English text. Additionally, I would like to kindly acknowledge the many helpful suggestions and remarks provided by the anonymous reviewers, which have greatly contributed towards improving the overall quality and readability of this paper. -

02Bodyetd.Pdf (193.2Kb)

Chapter I: Introduction Throughout history, there have been sporadic pockets or concentrations of intense intellectual activity around the globe. From Athens to Vienna, cities have often been associated with the historical eras in which they excelled. For example, the 5th century BC dramatists in Greece such as Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides helped to make Athens a leader in artistic creation during its prime. Vienna, the European capital of the music world during the 18th century, was a center of artistic creativity that included composers such as Mozart and Haydn. During the 1920s, the Weimar Republic held the distinction of being the epicenter of human thought and art, with Berlin firmly at the heart of this activity. A few of the familiar names connected to this era in German history are Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Theodor Adorno, Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, Fritz Lang, and F.W. Murnau. In addition to these individuals, many artistic and intellectual schools such as German Expressionism, the Frankfurt School, the Bauhaus, and “Der Sturm” are associated with the Weimar Republic. Socially, the period represents an equally intense atmosphere. The Weimar Republic thrived on entertainment, clubs, and night-life in general. Berlin was at the forefront of urban entertainment in Germany, rivaling the other major cities of the Western world. The nightscape of Berlin was marked by lighted signs advertising small cabaret clubs and lavish musicals. However, the streets were also lined with disabled war veterans, prostitutes, and businessmen alike, reflecting an increase of prostitution, debauchery and crime of which all are in some way connected to the unbelievable inflation that permeated all layers of social, cultural and political life in Weimar Germany during the Republic’s first few years. -

The Reality of the Imaginary—Architec- and Today, by Integrating the Latest Digital Ima- Ture and the Digital Image

The Reality of the techniques. Although they developed very distinct methods of analysis, they all proceeded from the Imaginary assumption that images are more than just repre- sentations. There is the typological approach of Aldo Rossi; there is the design method of O. M. Architecture and the Digital Image Ungers, which draws on metaphors and visual ana- logies; there is James Stirling’s postmodern collage technique—to name just a few. Others we might Jörg H. Gleiter mention include mvrdv’s diagrammatic and perfor- mative design processes and the de- and recon- struction technique employed by Peter Eisenman and Bernhard Tschumi. As a matter of fact, right from the discovery of perspective in the 15th century and the invention of Cartesian space, the imaging techniques used by I am honored to welcome you all to the 10th Inter- architects have always been more than just techni- national Bauhaus Colloquium. More than 30 years ques of representation. Friedrich Nietzsche once have passed since the 1st Bauhaus Colloquium was said that all our writing tools also work on our held in 1976. The first conference was held in thoughts. How true this is also for the field of archi- honour of the historical Bauhaus in Dessau and its tecture! Drawing on different imaging techniques— 50th anniversary. Since then, the focus of the collo- whether pencil, watercolor or the click of a quium has shifted from history to theory, and mouse—design processes transcribe a certain cultu- towards contemporary architecture and its critical ral logic onto the body of architecture, be it Carte- reassessment. -

The New Figuration Between Classicism and Superrealism

The New Figuration Between Classicism and Superrealism From the cultural crisis that took place after World War I there emerged new aesthetic proposals in Europe, ran- ging from Dadaist rejection of rationality to the antithetical return to order, clarity and simplicity predominant in the Italian and German scenes. In Spain, this translated into a new wave of figuration with classical and surrea- listic elements that appear in the work of artists like Salvador Dalí and Ángeles Santos. Art developed between the two poles which Realism and Surrealism represented, with the common aim of recovering the repre- sentation of the human body. Modern Spa- nish Realism didn’t look so much for the metaphysical quality of things, in the Italian style, so much as the irrational side that every excess of reality has. For that reason, many practitioners of Modern Realism had no difficulty in nor did they find contradic- tion in their encounter with the surreal. This oscillation between Magic Realism, Me- taphysical Painting, Surrealism, and even Hyperrealism was not something strange in the Spanish artistic reality; on the contrary, In 1927, Franz Roh’s essay After Expressionism, Magic Realism: Problems of the Newest stylistic nomadism was the characteristic European Painting was published. For Roh, the new variants of European post-Expres- of those years. sionism had their origin in the group of artists associated with the Roman magazine Valori The case of Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) Plastici, founded in 1918. The artists Carlo Carrà (1881-1966), Giorgio De Chirico (1888- was very special. Very informed of what was 1978), Alberto Savinio (1891-1952), and Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) contributed to being done in the rest of Europe through it as spokesmen of the metaphysical movement, considered the antecedent of European the magazine Valori Plastici and L’esprit Magic Realism.