04 August 2021 Aperto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOA 34-1A11-0209

ATLAS OF WORLD INTERIOR DESIGN ATLAS OF WORLD INTERIOR DESIGN Markus Sebastian Braun | Michelle Galindo (ed.) The Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographical information can be found on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de ISBN 978-3-03768-061-2 © 2011 by Braun Publishing AG www.braun-publishing.ch The work is copyright protected. Any use outside of the close boundaries of the copyright law, which has not been granted permission by the publisher, is unauthor-ized and liable for prosecution. This espe- cially applies to duplications, translations, microfilming, and any saving or processing in electronic systems. 1st edition 2011 Project coordination: Jennifer Kozak, Manuela Roth English text editing: Judith Vonberg Layout: Michelle Galindo Graphic concept: Michaela Prinz All of the information in this volume has been compiled to the best of the editors’ knowledge. It is based on the information provided to the publisher by the architects‘ and designers‘ offices and excludes any liability. The publisher assumes no responsibility for its accuracy or completeness as well as copyright discrepancies and refers to the specified sources (architects’ and designers’ offices). All rights to the IMPRINT photographs are property of the photographer (please refer to the picture). k k page 009 Architecture) | Architonic Lounge | Cologne | 88 k Karim Rashid| The Deutsche Rome | 180 Firouz Galdo / Officina del Disegno and Michele De Lucchi / aMDL | Zurich | 256 k Pia M. Schmid | Kaufleuten Festsaal -

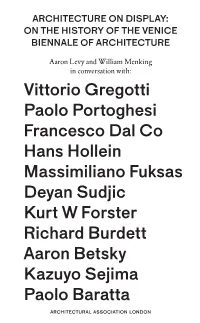

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Doriana Massimiliano Fuksas

DORIANA MASSIMILIANO FUKSAS Lo Studio Fuksas, guidato da Massimiliano e Doriana Fuksas, è uno studio di architettura internazionale con sedi a Roma, Parigi, Shenzhen. Di origini lituane, Massimiliano Fuksas nasce a Roma nel 1944. Consegue la laurea in Architettura presso l’Università “La Sapienza” di Roma nel 1969. E’tra i principali protagonisti della scena architettonica contemporanea sin dagli anni ‘80. E’ stato Visiting Professor presso numerose università, tra le quali: la Columbia University di New York, l’École Spéciale d’Architecture di Parigi, the Akademie der Bildenden Künste di Vienna, the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste di Stoccarda.Dal 1998 al 2000 è stato Direttore della “VII Mostra Internazionale di Architettura di Venezia”: “Less Aesthetics, More Ethics”. Dal 2000 è autore della rubrica di architettura, fondata da Bruno Zevi, del settimanale italiano “L’Espresso”. Doriana Fuksas nasce a Roma dove consegue la laurea in Storia dell’Architettura Moderna e Contemporanea presso l’Università “La Sapienza” di Roma nel 1979. Laureata in Architettura all’ESA -ÉcoleSpéciale d’Architecture- di Parigi, Francia. Dal 1985 collabora con Massimiliano Fuksas e dal 1997 è responsabile di “Fuksas Design”. Ha ricevuto diversi premi e riconoscimentiinternazionali. Nel 2013 è stata insignita dell’onorificenza di “Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres de la République Française” e nel 2002 di “Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres de la République Française”. Studio Fuksas, led by Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas, is an international architectural practice with offices in Rome, Paris, Shenzhen. Of Lithuanian descent, Massimiliano Fuksas was born in Rome in 1944. He graduated in Architecture from the University of Rome “La Sapienza” in 1969. -

FOR ZONCA C'era Una Volta Tre Milioni Di Anni Fa

FOR ZONCA C'era una volta tre milioni di anni fa ... Once upon a time three million years ago ... Doriana e Massimiliano PER ZONCA Serie di lampade “Candy Collection” per Zonca, 2013 “Candy Collection” lamps for Zonca, 2013 Lampade come caramelle colorate ripiene di luce. Lamps as coloured candies stuffed with light. La serie di lampade disegnate per Zonca parte da un The collection of lamps made for Zonca originates design geometrico, uno scrigno composto da dodici from a geometric design: a shrine made up of facce pentagonali che compongono la struttura twelve pentagonal sides composing the framework di ogni lampada. Seguendo un gioco di pieni e di of each lamp. The solids and voids effect is obtained vuoti, si passa da un corpo lampada concepito come from a body conceived as a frame which remains un’ossatura, dove la struttura è lasciata a vista, a un visible and a microporous covering for the sides. rivestimento delle facce con un motivo microforato. Whether they be used as floor, pendant or table Che siano da terra, sospese o utilizzate come oggetti lamps, the idea is to play with each lamp in order to d’arredo, l’idea è quella di giocare con ogni lampada create a unique ambiance. With such a collection per creare un’ambientazione unica. Si può dare vita of coloured lamps, conceived to be connected, a un’installazione, a una scultura, a un percorso overlapped and inlaid to generate an always luminoso attraverso questa serie di lampade colorate original lamp, it is possible to create an installation, disegnate per essere unite, sovrapposte, incastonate tra a sculpture or a luminous path. -

1) Prof. Luis Fernandez-Galiano (Chair

Press Release National Library Construction Company, Ltd. 16 Ibn Gvirol St., Jerusalem National Library Construction Company Appoints Judges for the Architecture Competition: (1) Prof. Luis Fernandez‐Galiano (Chair), (2) Prof. Rafael Moneo, (3) Prof. Massimiliano Fuksas, (4) Prof. Elinoar Komissar Barzachi, and (5) Architect Gaby Schwartz February 12, 2012 Submission of first stage of the Competition extended to 16 April, 2012, by request of the architects The National Library Construction Company today announced the members of the international Jury for the first stage of the architecture competition. The panel includes five architects – three international and two Israelis. The Israeli architects were selected based on a recommendation from the Competitions Committee of the Israeli Association of Architects. In Stage II of the competition, representatives of the library and of Yad Hanadiv will join the panel. Members of the panel: Prof. Luis Fernandez‐Galiano (Chair), Spain. Professor at the School of Architecture, Madrid Polytechnic University and Chief Editor of Arquitectura Viva – the most popular architecture publication in Spain. He has been a Visiting Professor at Yale University and Rice University in the US, as well as a Visiting Scholar at the Getty Research Institute. Prof. Rafael Moneo, Spain. Recipient of the Pritzker Prize for 1996. Headed the Harvard School of Architecture, where he is currently a Visiting Professor. Designed buildings primarily in Spain and in the US, including the expansion of the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Kursaal Palace Hotel in San Sebastián, a children’s hospital in Madrid, a science building at Columbia University in New York, and a new building for the Rhode Island School of Design. -

Brochure IMPRONTA.Pdf

IMPRONTALa gestualità e la forza iconica che caratterizzano i lavori dello studio Fuksas si ritrovano in tutti i pro- dotti che compongono la collezione Impronta: due lavabi, due piatti doccia, una cassettiera in acciaio lucido e due specchi in cui il concept originario ispira un sapiente gioco di riflessioni e luce. The handcraft and iconic power that marked Fuksas’ production are clearly visible in all Impronta product range: two washbasins, two shower trays, a polished steel drawer unit and two mirrors where an original concept creates a skilful game of reflections and light. Die Gestik und ikonische Kraft der Arbeiten aus dem Architektenbüro Fuksas sind in allen Artikeln der Kollektion Impronta erkennbar: zwei Waschbecken, zwei Duschtassen, ein Untertisch mit Schubladen aus poliertem Stahl und zwei Spiegel, in denen sich das ursprüngliche Konzept an einem gekonnten Spiel aus Reflexion und Licht inspiriert. 2 “ricordi di spiagge lontane, impronte leggere che il mare cancella e fa riaffiorare...” “memories of distant shores, light footprints that sea erases and makes them reappear...” “Erinnerungen an ferne Strände, leichte Fußabdrücke, die das Meer verlischt und wieder erscheinen lässt…“ 3 4 PHOTO ARCHIVIO FUKSAS La matrice organica è ricorrente nelle architetture dello studio Fuksas che abilmente usa metterla a con- trasto con strutture e geometrie più razionali. Dalla Nuvola del Nuovo Centro Congressi Eur di Roma, alla morbida copertura in vetro e acciaio dispiegata lun- go l’asse centrale del Nuovo Polo Fiera di Milano, al grande vortice scultoreo dello Zenith Music Hall di Strasburgo. The organic matrix is recurrent in Fuksas architecture design, and it is usually set in contrast with more rational structures and geometries. -

Cocktails and Conversations Dialogues on Architectural Design

COCKTAILS AND CONVERSATIONS DIALOGUES ON ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CURATED BY ABBY SUCKLE & WILLIAM SINGER JOHN RUBLE BRAD CLOEPFIL FRANCES HALSBAND DEBORAH BERKE ENRIQUE NORTEN RICHARD WELLER THOMAS BALSLEY ERIC OWEN MOSS TOM KUNDIG COCKTAILS AND CONVERSATIONS DIALOGUES ON ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CURATED BY ABBY SUCKLE & WILLIAM SINGER © 2018 by American Institute of Architects New York Chapter CONTENTS All Rights Reserved. No portion of the work may be reproduced or transmited in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from AIANY. i DEDICATIONS ISBN 978-1-64316-280-5 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Orders, inquiries and correspondence should be addressed to: iv ABOUT COCKTAILS AND CONVERSATIONS v INTRODUCTION American Institute of Architects New York Chapter Center For Architecture vii THE CONVERSATIONS 536 LaGuardia Place 165 ABOUT THE BARTENDERS New York, NY 10012 (212) 683 0023, [email protected] 168 ABOUT THE CURATORS 169 Printed in the United States PHOTO CREDITS AND NAPKIN SKETCHES The world may view architects’ idealism and aspiration as idiosyncratic, hopelessly romantic, if not naïve. Architects are constantly browbeaten for daring to dream oversized dreams. Why this slavish devotion to design and aspiration, the skeptic asks, when mean, cost-driven functionalism is all that’s being asked for? Architects don’t have many venues to discuss what makes architecture meaningful, how to “practice” in a world determined to bury aspiration under mandates and me-tooism. That’s the genius of Cocktails and Conversations and the Center for Architecture in New York. Audiences are happily liberated from over-serious formats such as academic lectures. -

Massimiliano Fuksas 26 Maggio 2011 Ore 17,30 Palazzo Tassoni Estense, Salone D’Onore

graphic design: Lab MD Material Design_Giulia Pellegrini Design_Giulia Material MD Lab design: graphic Massimiliano Fuksas 26 maggio 2011 ore 17,30 Palazzo Tassoni Estense, Salone d’Onore Ventennale della Fondazione Festival “To design today” Massimiliano Fuksas Massimiliano Fuksas (Roma, Italia, 1944) © Maurizio Marcato è sicuramente uno dei più noti architetti italiani a livello internazionale. Fermamente convinto della responsabilità “sociale” del fare architettura, da anni Fuksas è impegnato su un fronte di ricerca progettuale che lo porta ad affrontare le problematiche più differenziate, dalla scala architettonica a quella urbana, con la medesima sensibilità nei confronti delle specificità culturali del contesto di intervento. In particolare, nel suo lavoro Fuksas dedica notevole attenzione allo studio dei problemi urbani delle grandi aree metropolitane e specificamente alle periferie, incentrando la sua attività prevalentemente sulla realizzazione di opere pubbliche. Massimiliano Fuksas si laurea nel 1969 all’Università “La Sapienza” di Roma. Dopo avere fondato in quegli stessi anni lo studio professionale a Roma, successivamente crea il suo atelier parigino (1989) e poi quello viennese (1993). Da anni affianca a una solida attività professionale un intenso impegno accademico: è stato visiting professor presso l’École Spéciale d’Architecture di Parigi, l’Academy of Fine Arts di Vienna, la Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste di Stoccarda e la Columbia University di New York. Ha ricevuto numerosi premi internazionali tra cui il -

What Makes Architecture “Sacred”?

Uwe Michael Lang What Makes Architecture “Sacred”? Discussions of sacred architecture often revolve around the concept of beauty and its theological dimension. However, in the context of modernity, the question of beauty has been reduced to a subjective judgment, on which one can reason only to a limited extent. For those who do not share the presuppositions of the clas- sical philosophical tradition, the concept of beauty is elusive.1 When it comes to church architecture, it will not carry us very far. We may not think that Renzo Piano’s church of St. Pius of Pietrelcina in San Giovanni Rotondo works as a church (figure1 ), but how do we re- spond to someone who finds its architectural forms, or the space it creates for the assembly, “beautiful”? For these reasons I propose another concept that I believe will provide us with clearer categories for architecture in the service of the Church’s mission: the concept of the “sacred.” A reflection on the sacred also seems timely, because we customarily speak of “sacred” architecture, art, or music, without giving an account of what this attribute means. And yet for more than half a century theologians in the Catholic tradition have contested the Christian concept of the sa- cred. Ideas have consequences, and it seems evident to me that these theological positions are manifest in a style of buildings dedicated for logos 17:4 fall 2014 what makes architecture “sacred”? 45 worship that fail to express the sacred and hence are not adequate for the celebration of the liturgy. As a starting point for my argument, I should like to draw on the reflections of two well-known architects who designed important church buildings in the recent past. -

Program for the XXIII WORLD ARCHITECTS CONGRESS Torino 2008

Program for the XXIII WORLD ARCHITECTS CONGRESS Torino 2008 SUNDAY, JUNE 29, 2008 Venaria Reale Gardens > Congress inauguration ceremony and celebration of the 60th anniversary of the UIA MONDAY, JUNE 30, 2008 | CULTURE Lingotto Multipurpose Center and Palavela T – The Language of Contemporary Architecture What transmits contemporary architecture, how it’s done and how it should be done. The talk concerns the contemporary architect’s ability to listen to and fulfill people’s desires, transforming them into shapes for living. Is the architect able to hear the voices of those who will inhabit places and offer them the right solutions? Invited speakers: Aaron Betsky, Massimiliano Fuksas, Kengo Kuma, Marco de Michelis, Hani Rashid T – Creativity and the profession Architecture is creativity and technique: the talk is about how and how much creativity can give a project added value, imagining new solutions to the increasingly complex problems of living in contemporary and globalized society. Invited speakers: Zhu Pei, Dominique Perrault, Italo Rota, Mark Wiegly, Richard Saul Wurman MS – Restoring 20th century architecture Protecting and restoring modern architecture. MS – Material, site, construction Contemporary building: the features that evolve under the impulse of new technologies, globalization and knowledge, but also under the aspect of needs and local permanencies (areas of longstanding traditions or peripheral to great fluxes of transformation). MS – Young Architecture The session offers ideas and works from a number of young leaders in world architecture to hear about and discuss proposals for future cities and habitats. Invited speakers: Gary Chang, Studio Lo-Tek, Metrogramma, Luca Molinari, Bevk Perovic MS – Transmitting the Industrial City International debate on de-industrialization and strategies for planning and designing the post-industrial city, reusing and valorizing the landmarks, architectures and infrastructure of the industrial legacy. -

History and Futureof the Heart of Torino

Porta Palazzo History and future of the heart of Torino No small feat at all, considering the fact that over 5000 workers fill the square every day. All of the people involved coped with the inconveniences, 2 aware that reclamation and improvements to the 3 organisation of the layout of the entire square were necessary. Thanks to the constant commitment of engineers and workers, the square finally appeared in its new form during the Winter Olympics, without having to decentralise or move the market and its functions. Porta Palazzo’s market has been returned to the city It was an excellent example of expertise and efficiency! completely upgraded, after an extensive overhaul involving the square and the whole market. It was a brave act, which has allowed the upgrading and deep transformation of the square, while preserving its The local administration body prides itself on having ethnic and multi-hued character; treating with respect completed the works long before the set deadline, with the hundred-year stratification of stories, habits and life the least amount of inconvenience possible. It is an paces of the extraordinary world represented by the operation which has brought successful changes to market. technical, logistic and functional aspects and a reorganisation of the activities and the trades offered. Now, we can give back to the citizens a charming and unique place, a hub of goods and stories that is among Not only has Porta Palazzo become one of the most the most exceptional and loved in Torino. interesting and complete markets in Europe (and perhaps the largest open air), but it has also become one of the Porta Palazzo market is now a modern, functional and most efficient and better structured markets. -

To the Brochure

www.azrielifoundation.org.il The Azrieli Foundation is an a-political organization. Accordingly, the contents of the works exhibited for the David Azrieli Prize for Architectural Students express only the views of the presenting students themselves. DAVID AZRIELI ARCHITECTURE STUDENT PRIZE DAVID Greetings from Danna Azrieli, Dear Students, Graduates, Faculty, Architects and Architecture Enthusiasts, The David Azrieli Architecture Student Prize meets Israel’s young architects at an important milestone in their professional lives, when theory and practice converge. The Prize appraises and rewards students for their final project and their dream of making a personal imprint on the public space, the environment, society and public discourse. Over the years, the Prize has become an integral part of architecture education in Israel, with the heads of the five schools of architecture valuing it as a certificate of excellence. The final projects that made the short list are the best among the student works, and embody the extensive knowledge acquired by them during their years of study. As in previous years, this year Azrieli Foundation Canada – Israel presents generous grants to the three finalists - a first prize of 60,000 shekels, a second prize of 25,000 shekels, and a third prize of 15,000 shekels. The David Azrieli Prize honors and congratulates not only the winners, but all the students who submitted projects and contended for a place in the competition. I hope that this tradition will continue to inspire architecture students and the architecture community for many years to come. Best wishes and good luck, Danna Azrieli PAGE 2 DAVID AZRIELI ARCHITECTURE STUDENT PRIZE DAVID Arch.