Terrorism: the Effect of Positive Social Sanctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deafening Hate the Revival of Resistance Records

DEAFENING HATE THE REVIVAL OF RESISTANCE RECORDS "HATECORE" MUSIC LABEL: COMMERCIALIZING HATE The music is loud, fast and grating. The lyrics preach hatred, violence and white supremacy. This is "hatecore" – the music of the hate movement – newly revived thanks to the acquisition of the largest hate music record label by one of the nation’s most notorious hatemongers. Resistance Records is providing a lucrative new source of revenue for the neo-Nazi National Alliance, which ADL considers the single most dangerous organized hate group in the United States today. William Pierce, the group's leader, is the author of The Turner Diaries, a handbook for hate that was read by convicted Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh prior to his April, 1995 bombing attack. The National Alliance stands to reap thousands of dollars from the sale of white supremacist and neo-Nazi music. Resistance Records, which has had a troubled history, has been revitalized since its purchase last year by William Pierce, leader of the National Alliance. Savvy marketing and the fall 1999 purchase of a Swedish competitor have helped Pierce transform the once-floundering label into the nation’s premiere purveyor of "white power" music. Bolstering sales for Resistance Records is an Internet site devoted to the promotion of hatecore music and dissemination of hate literature. Building a Lucrative Business Selling Hate Since taking the helm of Resistance Records after wresting control of the company from a former business partner, Pierce has built the label into a lucrative business that boasts a catalogue of some 250 hatecore music titles. His purchase of Nordland Records of Sweden effectively doubled the label’s inventory to 80,000 compact discs. -

Brief for Petitioner in Roper V. Simmons, 03-633 (Capital Case)

No. 03-633 (CAPITAL CASE) ____________________________________ In the SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ___________________________________ DONALD P. ROPER, Superintendent, Potosi Correctional Center, Petitioner, v. CHRISTOPHER SIMMONS, Respondent. __________________________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Missouri ________________________________________ BRIEF FOR PETITIONER ________________________________________ JEREMIAH W. (JAY) NIXON Attorney General of Missouri JAMES R. LAYTON State Solicitor STEPHEN D. HAWKE Counsel of Record EVAN J. BU CHHEIM Assistant Attorneys General P.O. Box 899 Jefferson City, MO 65102 Phone: (573) 751-3321 Fax: (573) 751-3825 Attorneys for Petitioner i QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW (Capital Case) 1. Once this Court holds that a particular punishment is not “cruel and unusual,” and thus not barred by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, can a lower court reach a contrary decision based on its own analysis of evolving standards? 2. Is the imposition of the death penalty on a person who commits a murder at age seventeen “cruel and unusual,” and thus barred by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments? ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Questions presented ............................... i Table of Contents ................................ ii Table of Authorities ...............................v Opinions below ...................................1 Jurisdiction ......................................1 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ........2 Statement of the Case ..............................3 Summary of the Argument ..........................8 Argument I. Lower courts should be bound by this Court’s Eighth Amendment precedents, not set free to create a patchwork of differing constitutional rules, reflecting their own changing and subjective views of what constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment.” .....11 II. Principles of stare decisis argue against reversing the holding in Stanford v. Kentucky. ...............14 III. Reversing the Stanford v. -

Atauschwitzii There Were I.{O Gas Chambers

THERE\,{TEREI{O GASCHAMBE,RS ATAUSCHWITZII THERE WERE I.{O GAS CHAMBERS ATAUSCHWTTZTT Sensational claim by "Searchlight" columnist Expose the racists!! Expose the extrem ists ! ! Many anti-fascist activists believe that Searcliliglrf magazine is leading the tight against lascism, anti-Semitism, racial intolerance and extremist violence. Iloy, have we got news l'or theml Search /rglrt columnist Ray Hill claims to be a reformed Nazi. Presumably this means that he no longer denies the Holocausr? After all, only Nazis deny tbeHolocaust,as Searcliigh I never stops telling us. Then it should come as a big surprise to read in the magazine's nthere HILL STREET NEWS column lbr January 1994 that Hill makes the following amazing statement: were no gas chambers at Auschwitz" !!l Perhaps just as amazing is the lact that on the vera same page, Searchligltt carries an advertisement lbr a publicatinn called Bdtisit Patiot, (see page 3). This was the title of a magazine, now long defunct, published by the neo-Nazi llritish Movement. Now it belongs to a nragazine run by one Mark Cotterill, who has even been denounced by Scarcliigltl as a lascist. Ifthat surprises you, then rve have an even bigger shock in store fbr you, Lrecause Ray "there were no gas chambers at Ausclrwitz" Hill is tur lrom the only fornter Nazi connected with this supposedly anti-fascist magazine. Another refontrcd tar rightist is S<xia Hochfelder, at least, that was her maiden name. Today she's better known as Sonia Gable, correspondent of the Searchlight Educational Trust and wife of long time editor and publisher Gerry. -

The Social Roots of Islamist Militancy in the West

Valdai Papers #21 | July 2015 The Social Roots of Islamist Militancy in the West Emmanuel Karagiannis The Social Roots of Islamist Militancy in the West Introduction The phenomenon of Islamist militancy in the West has preoccupied the public, media and governments. The September 11 events aggravated the already strained relations between the West and the Muslim world. The fact that the perpetrators of the terrorist attacks were Muslims, who had travelled to the United States from European cities, brought the Old Continent’s Islamic communities to the spotlight. The homegrown Madrid and London bombings on March 11, 2004 and July 7, 2005, respectively, only confirmed in the eyes of some people the untrustworthiness of European Muslims. In the United States, there have also been some high-profile cases of jihadi attacks or plots in the post-9/11 period (e.g. the 2003 Brooklyn Bridge plot, 2009 Fort Hood shooting). While these attacks and plots were different from each other, they can be classified as cases of Islamist militancy. For the purpose of this study, Islamist militancy will be defined as the aggressive and often violent pursuit of a cause associated with Islam. Although it is very difficult to know precisely the number of Western Muslims who have been recruited by jihadi groups, a survey conducted by the Nixon Center revealed that there were 212 suspected and convicted terrorists implicated in North American and Western Europe between 1993 and 2003.1 In addition, Edwin Bakker’s study identified 242 individual cases of jihadi terrorists in Europe during 2001-2006.2 Most recently, there has been a resurgence of Islamist violence in Europe, Australia, Canada and the United States. -

Elections 2008:Layout 1.Qxd

ELECTIONS REPORT Thursday 1 May 2008 PREPARED BY CST 020 8457 9999 www.thecst.org.uk Copyright © 2008 Community Security Trust Registered charity number 1042391 Executive Summary • Elections were held on 1st May 2008 for the • The other far right parties that stood in the Mayor of London and the London Assembly, elections are small and were mostly ineffective, 152 local authorities in England and all local although the National Front polled almost councils in Wales 35,000 votes across five London Assembly constituencies • The British National Party (BNP) won a seat on the London Assembly for the first time, polling • Respect – The Unity Coalition divided into two over 130,000 votes. The seat will be taken by new parties shortly before the elections: Richard Barnbrook, a BNP councillor in Barking Respect (George Galloway) and Left List & Dagenham. Barnbrook also stood for mayor, winning almost 200,000 first and second • Respect (George Galloway) stood in part of the preference votes London elections, polling well in East London but poorly elsewhere in the capital. They stood • The BNP stood 611 candidates in council nine candidates in council elections outside elections around England and Wales, winning London, winning one seat in Birmingham 13 seats but losing three that they were defending. This net gain of ten seats leaves • Left List, which is essentially the Socialist them holding 55 council seats, not including Workers Party (SWP) component of the old parish, town or community councils. These Respect party, stood in all parts of the -

Hood Shooting Survivors to Face Gunman at Trial

• DOAAarmyaaN'T MISS: • ArmArmy • • Army Times August 5, 2013 • Photo gallery: Hood shooting survivors to face gunman at trial Aug. 5, 2013 - 06:00AM | 2 Comments Unknown Formatted: Font:(Default) Helvetica, 12 pt, Font color: Custom Color(RGB(44,44,44)) Retired Staff Sgt. Alonzo Lunsford holds one of the bullets removed from his body after he was wounded in the 2009 Fort Hood shooting rampage. Unknown Formatted: Font:(Default) Helvetica, 12 0 pt, Font color: Custom Color(RGB(44,44,44)), Hidden By Ramit Plushnick-Masti and Allen G. Breed The Associated Press Unknown Formatted: Font:(Default) Helvetica, 12 pt, Font color: Custom Color(RGB(44,44,44)) Zoom In a June 4 photo at his home in Lillington, N.C., retired Staff Sgt. Alonzo Lunsford describes his wounds from the 2009 Fort Hood shooting rampage. (Chuck Burton/AP) Key questions about Fort Hood shooting trial DALLAS – Maj. Nidal Hasan will stand trial in a court-martial that starts Tuesday for the shooting rampage at Fort Hood that left 13 people dead and more than 30 people wounded at the Texas Army post on Nov. 5, 2009. Here are some details about the case so far and what to expect from the trial: What charges does Hasan face? Hasan faces 13 specifications of premeditated murder and 32 specifications of attempted premeditated murder under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. If convicted, he would face the death penalty. Why has the case taken so long to prosecute? Judges in the case have granted a series of delays for preparation or other issues, often at the request of Hasan or his attorneys. -

06-22-2018: Petitioner's Notice of Supplemental

LEE BOYD IN THE MALVO, Fi'ed Petitioner COURT 0F APPEALS JUN 2 2 201B v. 0F MARYLAND mammal WWW5.3 STATE OF MARYLAND September Term, 2017 Respondent Pet. Docket N0. 476 PETITIONER’S NOTICE OF SUPPLEMENTAL AUTHORITY Petitioner respectfully notifies the Court of the Foufih Circuit’s decision in Malvo v. Mathew, — F.3d — 2018 WL 3058931 (4th Cir. Jun. 21, 2018) affirming the district court’s order vacating his life without parole sentences in Virginia and remanding for resentencing. A copy 0f the decision is enclosed. Respectfully submitted, I“. Kiran W Iyer Assistant Public Defender CPF # 1702020011 Office of the Public Defender Appellate Division 6 Saint Paul Street, Suite 1302 Baltimore, Maryland 2 1 202- 1 608 Work: (410) 767-0668 Facsimile: (410) 333-8801 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I HEREBY CERTIFY that on this 22 day 0f June, 2018, three copies of the foregoing were delivered to Carrie J. Williams Chief Counsel Criminal Appeals Division Office of the Attorney General 200 Saint Paul Place, 17th Floor Baltimore, Maryland 2 1202 Three copies were also mailed, postage pre—paid, to Russell P. Butler, Esq., Victor Stone, Esq., and Kristin M. Nuss, Esq. Maryland Crime Victims’ Resource Center, Inc. 1001 Prince George’s B1Vd., Suite 750 Upper Marlboro, Maryland 20774 /7 “#22 fl; Kiran Iyer PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT No. 17-6746 LEE BOYD MALVO, Petitioner - Appellee, V. RANDALL MATHENA, Chief Warden, Red Onion State Prison, Respondent - Appellant. HOLLY LANDRY, Amicus Supporting Appellee. No. 17-6758 LEE BOYD MALVO, Petitioner - Appellee, V. -

Muslim-American Terrorism in the Decade Since 9/11

Muslim-American Terrorism in the Decade Since 9/11 CHARLES KURZMAN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL FEBRUARY 8, 2012 Muslim-American Terrorism Down in 2011 This is the third annual report on Muslim‐American terrorism suspects and perpetrators published by the Twenty Muslim-Americans were indicted for Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security. violent terrorist plots in 2011, down from 26 the year before, bringing the total since 9/11 The first report, co‐authored by David Schanzer, to 193, or just under 20 per year (see Figure Charles Kurzman, and Ebrahim Moosa in early 2010, 1). This number is not negligible -- small also examined efforts by Muslim‐Americans to prevent numbers of Muslim-Americans continue to radicalization. The second report, authored by Charles radicalize each year and plot violence. Kurzman and issued in early 2011, also examined the However, the rate of radicalization is far less source of the initial tips that brought these cases to the than many feared in the aftermath of 9/11. In attention of law‐enforcement authorities. This third early 2003, for example, Robert Mueller, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, report, authored by Charles Kurzman and issued in told Congress that “FBI investigations have early 2012, focuses on cases of support for terrorism, revealed militant Islamics [sic] in the US. We in addition to violent plots. These reports, and the data strongly suspect that several hundred of these on which they are based, are available at 1 extremists are linked to al-Qaeda.” http://kurzman.unc.edu/muslim‐american‐terrorism. -

History – 2000 Thru 2014

This Time in History NOTABLE EVENTS IN WORLD/U.S. HISTORY - CONTINUED 2000 - 2014 2008 Oil prices in the U.S. hit a record $147 per barrel IMMANUEL MILESTONES Global financial crisis - stock market crashed 2006 Pre-school added to school 2009 Fort Hood shooting - 12 servicemen killed, 31 injured An association formed with Grace Church in Hutchinson, thus Immanuel H1N1 (swine flu) global pandemic Lutheran School and Children of Grace Pre-School 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill - 4.9 million barrels of oil spilt into the Gulf of Mexico Pastors 2011 Gabrielle Giffords, U.S. Representative, shot & critically injured in Tucson, Ronald Siemers (1995-2001) Daniel Reich (2001-present) AZX, 6 others killed Principals/Teachers Osama bin Laden, U.S. most wanted terrorist, killed by U.S. Navy Seals in Timothy Schuh (1997-2006) Cheryl Schuh (1997-2006) Pakistan Koreen Koehler (2000-2002) Leanne Reich (2002-2004) A nuclear catastrophe in Tokyo resulted from a 9.0 earthquake in Japan Justin Groth (2006-2010) Heidi Groth (2006-2010) One of the deadliest tornado season known in U.S. history - amongst the most Kristin (Slovik) Utsch (2008-present) Alex Vandenberg (2010-present) devastating was in Joplin, MO Stephanie Vandenberg (2010-present) 2012 Hurricane Sandy caused devastation along the east coast - 132 deaths; $82 billion in damages WELS/LUTHERAN KEYPOINTS Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, CT - killed 26 people 2001 Time of Grace began airing on TV of which 20 were children between the ages of 6 and 7 2008 Christian Worship Supplement published 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings - two pressure cookers used in explosions; killed U.S. -

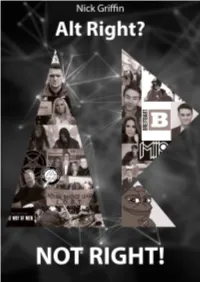

Alt Right? – NOT RIGHT! 3

Alt Right? – NOT RIGHT! 3 © Nick Griffin: ALT RIGHT? – NOT RIGHT! Printed & published by the Rosslyn Institute for Traditional and Geopolitical Studies in 2017 4 Alt Right? – NOT RIGHT! CONTENT Executive Summary 5 The London Forum – Rehabilitating Pederasty 47 Personal Introduction By The Author 5 Bain Dewitt 50 “By their fruits...” 52 Introduction 7 Western Spring 53 The ‘Gay’ Takeover 8 Nazi Sex Offenders & Woman-Haters 54 Milo Yiannopoulos 9 National Action 54 Breitbart and Steve Bannon 11 Ryan Fleming – Satanist pervert 55 Breitbart and the Mercers 11 The Pink Swastika 57 Daily Stormer – Equal opportunity haters 58 “Zionism” – A Fact, Not A Codeword 14 Weev – Fantasies of violence against ‘lascivious’ women 59 Power Grab On The UK’s ‘Soft Right’ 14 Peter Whittle & The New Culture Forum 16 Charlottesville – The Strange Characters Behind Douglas Murray & The Henry Jackson The Disaster 61 Society 16 Augustus Invictus 62 New Culture Forum 18 Jason Kessler 62 Tommy Robinson – The English Defence League Baked Alaska 63 & Beyond 21 Christopher Cantwell 64 Matt Heimbach 64 Rebel Media & The Alt-Lite 23 Pax Dickinson 64 Gavin McInnes & The Proud Boys 23 Johnny Monoxide 64 Based Stickman 24 Based Stickman 65 Augustus Sol Invictus 25 Richard Spencer 65 Laura Loomer 25 ‘Led’ into a trap 66 Rebel UK 26 After Charlottesville – The lunacy continues... 67 Info-Wars 29 Paul Joseph Watson 29 WHY – Who Wants To Homosexualise The ‘Right’? 68 Pushing for endless war 69 Tommy Robinson, Peter McLoughlin & The New Full spectrum dominance 72 English Review -

Roper V. Simmons: the Execution of Juvenile Criminal Offenders in America and the International Community's Response

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 22 Issue 3 Volume 22, Winter 2008, Issue 3 Article 5 Roper v. Simmons: The Execution of Juvenile Criminal Offenders in America and the International Community's Response Jacqulyn Giunta Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROPER V. SIMMONS: THE EXECUTION OF JUVENILE CRIMINAL OFFENDERS IN AMERICA AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY'S RESPONSE JACQULYN GIUNTA* INTRODUCTION The execution of juvenile criminal offenders is in the spotlight of both the national and international legal arena. As the sole proponent of this policy throughout the international community, the United States has faced intense criticism in upholding this archaic form of punishment. The Supreme Court, for a long time, held there was no national consensus rejecting juvenile execu- tions and not a violation of the Eighth Amendment. In the 2005 decision of Roper v. Simmons,1 however, the Supreme Court over- turned Stanford v. Kentucky2 holding that juvenile executions were a violation of the cruel and unusual punishment. This note will analyze the shift in American opinion throughout the past three decades and focus on the international policy on juvenile executions. In addition, this Note will consider the weight of au- thority the Supreme Court gives the international community in deciding its cases. -

COMBAT STRESS Harnessing Post-Traumatic Stress for Service Members, Veterans, and First Responders

The American Institute of Stress COMBAT STRESS Harnessing Post-Traumatic Stress for Service Members, Veterans, and First Responders Volume 8 Number 3 Fall 2019 Fort Hood Massacre Tenth Anniversary Nothing has changed: Still Workplace Violence AND the Escalating Epidemic of Veteran Suicides. The mission of AIS is to improve the health of the The mission of AIS is to improve the health of the community and the world by setting the standard of community and the world by setting the standard of excellence of stress management in education, research, excellence of stress management in education, research, clinical care and the workplace. Diverse and inclusive, clinical care and the workplace. Diverse and inclusive, The American Institute of Stress educates medical The American Institute of Stress educates medical practitioners, scientists, health care professionals and practitioners, scientists, health care professionals and the public; conducts research; and provides information, the public; conducts research; and provides information, training and techniques to prevent human illness related training and techniques to prevent human illness related to stress. to stress. AIS provides a diverse and inclusive environment that AIS provides a diverse and inclusive environment that fosters intellectual discovery, creates and transmits fosters intellectual discovery, creates and transmits innovative knowledge, improves human health, and innovative knowledge, improves human health, and provides leadership to the world on stress related topics. provides leadership to the world on stress related topics. Harnessing Post-Traumatic Stress for Service Members, Veterans, and First Responders COMBAT STRESS We value opinions of our readers. Please feel free to contact us with any comments, suggestions or inquiries.