Nusreta Sivac Transcribed Interview English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Prijedor-Genocide 1

PART 1. THE PRIJEDOR GENOCIDE The Prijedor genocide [1][2][3] , refers to numerous war crimes committed during the Bosnian war by the Serb political and military leadership mostly on Bosniak civilians in the Prijedor region of Bosnia-Herzegovina. After the Srebrenica genocide, it is the second largest massacre committed during the Bosnian war in 1992. Around 5,200 Bosniaks and Croats from Prijedor are missing or were killed during the massacre period, and around 14,000 people in the wider region of Prijedor (Pounje). [4] Contents • 1 Background • 2 Political developments before the takeover • 3 Takeover • 4 Armed attacks against the civilians o 4.1 Propaganda o 4.2 Strengthening of Serb forces o 4.3 Marking of non-Serb houses o 4.4 Attack on Hambarine o 4.5 Attack on Kozarac • 5 Camps o 5.1 Keraterm camp o 5.2 Omarska camp o 5.3 Trnopolje camp o 5.4 Other detention facilities • 6 Killings in the camps • 7 References • 8 See also • 9 External links Background Following Slovenia’s and Croatia’s declarations of independence in June 1991, the situation in the Prijedor municipality rapidly deteriorated. During the war in Croatia, the tension increased between the Serbs and the communities of Bosniaks and Croats. Bosniaks and Croats began to leave the municipality because of a growing sense of insecurity and fear amongst the population which was caused by Serb propaganda which became increasingly visible. The municipal newspaper Kozarski Vjesnik started publishing allegations against the non-Serbs. The Serb media propagandised the idea that the Serbs had to arm themselves. -

Download (1233Kb)

Original citation: Koinova, Maria and Karabegovic, Dzeneta . (2016) Diasporas and transitional justice : transnational activism from local to global levels of engagement. Global Networks (Oxford): a journal of transnational affairs . Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/83210 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: "This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Koinova, Maria and Karabegovic, Dzeneta . (2016) Diasporas and transitional justice : transnational activism from local to global levels of engagement. Global Networks (Oxford): a journal of transnational affairs ., which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/glob.12128 This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving." A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. -

Former Yugoslavia

Former Yugoslavia The information below if based on the UN International Criminal Court for the former Yugoslavia's Landmark cases - Duško Tadić: first-ever trial for sexual violence against men1 This trial of the former Bosnian Serb Democratic Party’s local board president from Kozarac, northwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina, made history in many ways. It was the first international war crimes trial since Nuremberg and Tokyo. Just as importantly, it was the first international war crimes trial involving charges of sexual violence. The trial proved to the world that the nascent international criminal justice system could end impunity for sexual crimes and that punishing perpetrators was possible. The Trial Chamber found how after taking over the area of Prijedor, in northwestern of BiH, Serb forces confined thousands of Muslims and Croats in camps. In a horrific incident in the Omarska Camp, one of the detainees was forced by uniformed men, including Duško Tadić, to bite off the testicles of another detainee. In May 1997, the Trial Chamber found Tadic guilty of cruel treatment (violation of the laws and customs of war) and inhumane acts (crime against humanity) for the part he played in this and other incidents. Two years later, on appeal, Tadic was additionally sentenced for grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva conventions: inhumane treatment and wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to the body or health. In the Judgement, the Appeals Chamber set out that “Through his presence, Duško Tadić aided and encouraged the group of men actively taking part in the assault. Of particular concern here is the cruelty and humiliation inflicted on the victim and the other detainees”. -

The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory

The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory Elmedin Žunić ORCID ID: 0000-0003-3694-7098 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Melbourne Faculty of Fine Arts and Music July 2018 Abstract The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory concerns the representation of historic and traumatogenic events in art through the specific case of the war in Bosnia 1992-1995. The research investigates an aftermath articulated through the Freudian concept of Nachträglichkeit, rebounding on the nature of representation in the art as always in the space of an "afterness". The ability to represent an originary traumatic scenario has been questioned in the theoretics surrounding this concept. Through The Bosnian Case and its art historical precedents, the research challenges this line of thinking, identifying, including through fieldwork in Bosnia in 2016, the continuation of the war in a war of images. iii Declaration This is to certify that: This dissertation comprises only my original work towards the PhD except where indicated. Due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used. This dissertation is approximately 40,000 words in length, exclusive of figures, references and appendices. Signature: Elmedin Žunić, July 2018 iv Acknowledgements First and foremost, my sincere thanks to my supervisors Dr Bernhard Sachs and Ms Lou Hubbard. I thank them for their guidance and immense patience over the past four years. I also extend my sincere gratitude to Professor Barbara Bolt for her insightful comments and trust. I thank my fellow candidates and staff at VCA for stimulating discussions and support. -

Teacher Information Sheet Genocide in Bosnia

Teacher information sheet Genocide in Bosnia The population of Bosnia and Herzegovina (referred to as ‘Bosnia’ here) consists of: • Bosniaks – Bosnian Muslims • Bosnian Serbs – Serb Orthodox Christians who have close cultural ties with neighbouring Serbia • Bosnian Croats – Roman Catholics who have close cultural ties with neighbouring Croatia Bosnia’s history Flag of Bosnia, adopted in 1998 Between 1991-1994 Yugoslavia disintegrated into five states – Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Macedonia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (later known as Serbia and Montenegro). Bosnia declared independence in 1992. This was resisted by the Bosnian Serb population who saw their future as part of ‘Greater Serbia’, sparking a civil war over land. The Bosnian War Bosnia became the victim of the Bosnian Serbs’ wish for political domination, which they were prepared to achieve by isolating ethnic groups and, if necessary, exterminating them. A campaign of war crimes, ‘ethnic cleansing’ and genocide was perpetrated by Bosnian Serb troops under the orders of Slobodan Milošević. Sarajevo, the capital city of Bosnia, was under siege for nearly four years - the longest siege in modern warfare. The Serb-controlled army surrounded the city, bombing it, killing more than 10,000 people and destroying cultural monuments. Persecution From 1991, in Prijedor, north-west Bosnia, non-Serbs were forced to wear white armbands and certain newspapers, radio stations and television stations began to broadcast anti-Croat and anti- Bosniak propaganda. Non-Serbs were sent to concentration camps which had been set up in mid-1992. Women were taken to Trnopolje camp where systematic rape took place on a regular basis. -

The International Criminal Tribunal

MICT-13-55-A 2970 A2970-A2901 15 March 2017 AJ THE MECHANISM FOR INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNALS No. MICT-13-55-A IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Theodor Meron Judge William Hussein Sekule Judge Vagn Prusse Joensen Judge Jose Ricardo de Prada Solaesa Judge Graciela Susana Gatti Santana Registrar: Mr Olufemi Elias Date Filed: 15 March 2017 THE PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARADZIC Public Redacted Version RADOVAN KARADZIC’S RESPONSE BRIEF ________________________________________________________________________ Office of the Prosecutor: Laurel Baig Barbara Goy Katrina Gustafson Counsel for Radovan Karadzic Peter Robinson Kate Gibson No. MICT-13-55-A 2969 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 4 II. THE PROSECUTION’S APPEAL .................................................................................. 5 1. The Excluded Crimes were Rightly Excluded .............................................................. 5 A. The Trial Chamber committed no legal error in identifying another reasonable inference ...................................................................................................... 7 B. The finding that the Excluded Crimes did not form part of the JCE was reasonable .................................................................................................................... 10 1. The Trial Chamber never found that President Karadzic knew the Excluded Crimes were necessary to achieve the common criminal purpose......... -

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarah Quillinan ORCHID ID: 0000-0002-5786-9829 A dissertation submitted in total fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2019 School of Social and Political Sciences University of Melbourne THIS DISSERTATION IS DEDICATED TO THE WOMEN SURVIVORS OF WAR RAPE IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA WHOSE STRENGTH, FORTITUDE, AND SPIRIT ARE TRULY HUMBLING. i Contents Dedication / i Declaration / iv Acknowledgments / v Abstract / vii Note on Language and Pronunciation / viii Abbreviations / ix List of Illustrations / xi I PROLOGUE Unclaimed History: Memoro-Politics and Survivor Silence in Places of Trauma / 1 II INTRODUCTION After Silence: War Rape, Trauma, and the Aesthetics of Social Remembrance / 10 Where Memory and Politics Meet: Remembering Rape in Post-War Bosnia / 11 Situating the Study: Fieldwork Locations / 22 Bosnia and Herzegovina: An Ethnographic Sketch / 22 The Village of Selo: Republika Srpska / 26 The Town of Gradić: Republika Srpska / 28 Silence and the Making of Ethnography: Methodological Framework / 30 Ethical Considerations: Principles and Practices of Research on Rape Trauma / 36 Organisation of Dissertation / 41 III CHAPTER I The Social Inheritance of War Trauma: Collective Memory, Gender, and War Rape / 45 On Collective Memory and Social Identity / 46 On Collective Memory and Gender / 53 On Collective Memory and the History of Wartime Rape / 58 Conclusion: The Living Legacy of Collective Memory in Bosnia and Herzegovina / 64 ii IV CHAPTER II The Unmaking -

Lesson Plan 1 Lesson 1 of 3 – a Personal Experience of the Bosnian War

The Forgiveness Project Forgiving the Unforgivable – Lesson Plan 1 Lesson 1 of 3 – A personal experience of the Bosnian War Kemal Pervanic’s story – Part 1 55 mins (film duration 9 mins) © 2017 The Forgiveness Project | www.theforgivenessproject.com A personal experience of the Bosnian War Please ensure the staff member facilitating this lesson has an understanding of the Bosnian War. A timeline is at the end of this lesson plan. This short clip (7 mins) from the 1995 BBC documentary, Death of Yugoslavia, sets out the process and scale of ethnic cleansing during the Bosnian War: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VbNocQORWQ8. Please note this contains very graphic scenes and is not suitable to be shown to the students. Lesson objective: 1. To be able to explain the personal experience of someone who has lived through the Bosnian War. Key vocabulary: Yugoslavia, nationalism, persecuted, concentration camp, Omarska camp, Prijedor massacre, demonise. Teacher activity Learner activity Time Who is Kemal Pervanic / Profile of Kemal Read the passage in the 5 mins Invite students to read the passage in their student booklet in student booklet and pairs and to complete the profile of Kemal as a teenager. complete the profile. Kemal Pervanic’s story / Film notes Watch the film and make 20 mins Introduce the story and the ground rules. Watch the film and notes or write questions ask students to make notes or questions throughout the film of throughout the film of any any words they don’t fully understand or parts of the story they words you don’t fully would like to discuss afterwards. -

Case Information Sheet

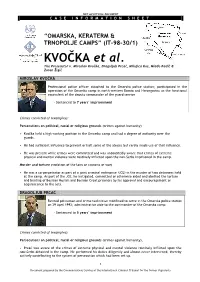

NOT AN OFFICIAL DOCUMENT CASE INFORMATION SHEET “OMARSKA, KERATERM & TRNOPOLJE CAMPS” (IT-98-30/1) KVOĈKA et al. The Prosecutor v. Miroslav Kvočka, Dragoljub Prcać, Milojica Kos, Mlađo Radić & Zoran Žigić MIROSLAV KVOĈKA Professional police officer attached to the Omarska police station; participated in the operation of the Omarska camp in north-western Bosnia and Herzegovina as the functional equivalent of the deputy commander of the guard service - Sentenced to 7 years’ imprisonment Crimes convicted of (examples): Persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds (crimes against humanity) • Kvoĉka held a high-ranking position in the Omarska camp and had a degree of authority over the guards. • He had sufficient influence to prevent or halt some of the abuses but rarely made use of that influence. • He was present while crimes were committed and was undoubtedly aware that crimes of extreme physical and mental violence were routinely inflicted upon the non-Serbs imprisoned in the camp. Murder and torture (violation of the laws or customs of war) • He was a co-perpetrator as part of a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) in the murder of two detainees held at the camp. As part of the JCE, he instigated, committed or otherwise aided and abetted the torture and beating of Bosnian Muslim and Bosnian Croat prisoners by his approval and encouragement or acquiescence to the acts. DRAGOLJUB PRCAĆ Retired policeman and crime technician mobilised to serve in the Omarska police station on 29 April 1992; administrative aide to the commander of the Omarska camp - Sentenced to 5 years’ imprisonment Crimes convicted of (examples): Persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds (crimes against humanity), • Prcać was aware of the crimes of extreme physical and mental violence routinely inflicted upon the non-Serbs detained in the camp. -

MOMCILO KRAJISNIK and BILJANA PLAVSIC AMENDED

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Case No. IT-00-39 & 40-PT THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST MOMCILO KRAJISNIK and BILJANA PLAVSIC AMENDED CONSOLIDATED INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, pursuant to her authority under Article 18 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia ("the Statute of the Tribunal"), charges: MOMCILO KRAJISNIK and BILJANA PLAVSIC with GENOCIDE, CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY and VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS AND CUSTOMS OF WAR as set forth below: THE ACCUSED 1. Momcilo KRAJISNIK, son of Sreten and Milka (née Spiric) was born on 20 January 1945 in Zabrdje, municipality of Novi Grad, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was a leading member of the Serbian Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina ("SDS") and he served on a number of SDS bodies and committees. On 12 July 1991, Momcilo KRAJISNIK was elected to the Main Board of the SDS. He was President of the Assembly of Serbian People in Bosnia and Herzegovina ("Bosnian Serb Assembly") from 24 October 1991 until at least November 1995. He was a member of the National Security Council of the Bosnian Serb Republic and from the beginning of June 1992 until 17 December 1992, he was a member of the expanded Presidency of the Bosnian Serb Republic. 2. Biljana PLAVSIC, daughter of Svetislav, was born on 7 July 1930 in Tuzla, Tuzla municipality, Bosnia and Herzegovina. She was a leading member of the SDS from the period of its establishment in Bosnia and Herzegovina. From 18 November 1990 until April 1992, Biljana PLAVSIC was a member of the collective Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. -

The State-Building-Reconciliation Nexus: A

THE STATE-BUILDING-RECONCILIATION NEXUS: A CRITICAL OBSERVATION OF PEACEBUILDING IN BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA By Louis Francis Monroy Santander A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY International Development Department School of Government and Society College of Social Sciences University of Birmingham December 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis analyses peacebuilding in Bosnia and Herzegovina, looking at the relation between state-building and transitional justice. It relies on reconciliation, as a socially constructed term, to look at how international and civil society organizations in the country, as well as Bosnian citizens, perceive processes put in place after the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords. In doing so, it contributes to debates in literature discussing how to approach peacebuilding holistically, identifying spaces for connecting top-down and bottom-up processes, supporting the establishment of a sustainable peace. The thesis relies on a constructivist framework, seeking to understand the frameworks and mindsets shaping reconciliation as a working concept for international and civil society associations and as an experience for Bosnian citizens. -

Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina

GENOCIDE IN BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS APRIL 4, 1995 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 104-X-X] Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/csce 1 GENOCIDE IN BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA TUESDAY, APRIL 4, 1995 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE WASHINGTON, DC. The Commission met in room 2322, Rayburn House Office Building, at 2 p.m., the Honorable Christopher Smith, Chairman, presiding. Commission members present: Hon. Christopher Smith, Chairman; Hon. Alfonse D’Amato, Co-Chairman; Hon. Frank Wolf; Hon. Steny H. Hoyer; and Hon. Benjamin Cardin. Also present: Hon. James Moran and Hon. Frank R. Lautenberg. OPENING STATEMENT OF CHAIRMAN CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH Chairman SMITH. The Commission will come to order. Good after- noon, ladies and gentlemen. The subject of today’s hearing is genocide- -genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Commission’s intent is to focus on the extent to which ethnic cleansing, the destruction of cultural sites, and associated war crimes and crimes against humanity constitute geno- cide in Bosnia and other parts of the former Yugoslavia. With this fo- cus, we hope to learn more about the intent of those committing these acts and the extent to which the war crimes were ordered from the military and the political leadership. I believe this hearing is of critical importance. This week, as Bosnia enters its fourth year of war, we on the outside have become fatigued by the daily developments there and the endless discussion of policy op- tions.