Before the Story Begins: on <Emphasis Type="Italic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 the Story Begins the Following Story Was Told on a Hot Day, Whilst People Were Sitting on a Low-Lying Salt Flat, in the Sun

10 2 The Story Begins The following story was told on a hot day, whilst people were sitting on a low-lying salt flat, in the sun. We had just previously returned from the mangroves, having collected a large amount of ku thali (“longbums”, Telescopium telescopium) and ku warrgi (“mangrove worms”, Teredo spp.), and had sat down to have a cup of tea and feast on the haul. Where the transcribed passage commences, I was walking away from the feasting group, leaving the flash-ram recorder running, so as to record the conversation. Present were two senior women, Phyllis and Elizabeth, three of Elizabeth’s granddaughters – two teenagers (AC and MC), and a third granddaughter in her twenties, JC. Also present was JD, the husband of JC (also in his twenties). Elizabeth is a traditional owner of the place we were visiting, in that the area forms part of the estate of her patrilineal clan.4 The immediately preceding talk was about the name of the country and about which way the old foot-tracks used to go. Fragment 1 On the Flat (2005-07-05JB01) !"!! ! ! #$%&'(! !'!! )*+,! -./0.!1*.23,!4566.67.2!63859//+.:" This might be where they fought with spears. !;!! <,5=! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#>>!>>>!>9!$9%! !&!! ! ! #$%;;(! !?!! )*+,! @.A.B!C2.!67.//.673!1*36773!4566.26385//+3%! Isn’t that right? But which way was that shooting? !D!! ! ! #!%D(! E$!! )*+,! F5=.8G1%H! EI!! <,5=! HJG+¿! E!!! ! ! #$%"?(! EE!! )*+,! K.%6+5/0.!+.6.!45,.245!67.,,.!67.%! Right here on the big salt plain, hey. E"!! ! ! #%(! E'!! <,5=! 0.!67.,,.%! The big one ((salt plain)). -

PENGALAMAN FANATISME PADA K-POPERS (Studi Kasus ARMY Dan ONCE Di Kota Medan)

PENGALAMAN FANATISME PADA K-POPERS (Studi Kasus ARMY dan ONCE di Kota Medan) SKRIPSI Diajukan Guna Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Sosial dalam Bidang Antropologi Sosial Oleh: Marintan Manik 160905078 PROGRAM STUDI ANTROPOLOGI SOSIAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2021 Universitas Sumatera Utara ii Universitas Sumatera Utara iii Universitas Sumatera Utara UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK PERNYATAAN ORIGINALITAS PENGALAMAN FANATISME PADA K-POPERS (Studi Kasus ARMY dan ONCE di Kota Medan) SKRIPSI Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa dalam skripsi ini tidak terdapat karya yang pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh gelar kesarjanaan di suatu perguruan tinggi dan disepanjang pengetahuan saya juga tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang pernah ditulis atau diterbitkan oleh orang lain, kecuali yang tertulis diacu dalam naskah ini dan disebutkan dalam daftar pustaka. Apabila dikemudian hari terbukti lain atau tidak seperti yang saya nyatakan disini, saya bersedia diproses secara hukum dan siap menanggalkan gelar kesarjanaan saya. Medan, Februari 2021 Marintan Manik iv Universitas Sumatera Utara ABSTRAK Marintan Manik, 2020. Judul Skripsi PENGALAMAN FANATISME PADA K- POPERS (Studi Kasus ARMY dan ONCE di Kota Medan). Skripsi ini bertujuan untuk melihat bagaimana pengalaman fanatisme pada K-Popers, dengan studi kasus ARMY dan ONCE di Kota Medan. Rasa suka yang berlebihan kepada idola K-Pop seringkali melahirkan sikap fanatik dalam diri K- Popers. Rasa suka yang berlebihan ini akan melahirkan berbagai tindakan fanatisme. Setiap K-Popers memiliki pengalaman fanatisme yang berbeda-beda tergantung pada kemampuan mereka. K-Popers pria dan wanita juga cenderung memiliki pengalaman yang berbeda, didasarkan pada aturan-aturan gender yang berlaku dalam masyarakat. -

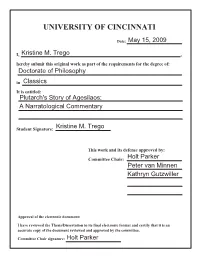

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

The Glow & When You're Falling [Lig

ALICE in WONDERLAND 1. PROLOGUE - DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE IN WHICH THREE SISTERS LEAVE THEIR WORLD BEHIND SONGS: THE GLOW & WHEN YOU’RE FALLING [LIGHTS UP. SHOWCASE: VOICE lines the sides of the stage. Music begins and they sing:] THE GLOW LOOK AROUND TAKE IN ALL THAT YOU SEE YOU JUST MIGHT BE SURPRISED A WORLD OF ENCHANTMENT AND PURE MAJESTY YOU'LL BE DISCOVERING THE HERO THAT YOU'RE MEANT TO BE [Curtain opens. LORINA, ALICE and EDITH are having a picnic. ALICE and EDITH lay on a small hillside looking to the sky and pointing to clouds. LORINA remains on the picnic blanket, trying to be irritated with her sisters, yet it is also clear she loves them dearly.] THE STORY BEGINS WITH THE LIGHT IN YOUR HEART A FANTASY, A DREAM AND A SPARK ONCE YOU BELIEVE YOU ARE READY TO SHINE THE WONDER INSIDE YOU WILL SHOW YOU ARE THE GLOW... FEEL YOUR STRENGTH, YOU CAN FACE THE WORLD BELIEVE EVERY DAY, EVERYTHING IS POSSIBLE A MAGICAL JOURNEY AWAITS... EDITH I see... a duck... a white duck... And a white rabbit! LORINA They’re clouds, Edith. Of course they’re white. Come finish your plate. ALICE I see a mad queen — and she wants to cut off your head! EDITH No! LORINA Edith, Alice is only teasing. Alice, if you’re going to play, play nice. ALICE in WONDERLAND 2. ALICE It’s so dull here. I want to be on the river. (new thought) I wish it were summer and time for the fair! LORINA Unless you were on the river or at the fair and then you’d wish to be somewhere else. -

Prose Fiction--Short Story, Novel. Literature

R E F O R T RESUMES ED 015 905 24 TE 909 295 PROSE FICTION--SHORT STORY, NOVEL.LITERATURE CURRICULUM V. TEACHER ANC STUDENT VERSIONS. BY- KITZHABER. ALBERT R. OREGON UNIV., EUGENE REPORT NUMBER CRP-H-149-72 REPORT NUMBER BR-5-0366-72 CONTRACT OEC-5-10-319 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$7.28 180P. DESCRIPTORS- *CURRICULUM GUIDES. *ENGLISHCURRICULUM, *ENGLISH INSTRUCTION, *NOVELS. *SHORT STORIES.FICTION. GRADE 11. INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS, LITERARY ANALYSIS,LITERATURE. SECONDARY EDUCATION. STUDY GUIDES, SYMBOLS(LITERARY). TEACHING GUIDES. TWENTIETH CENTURYLITERATURE. CURRICULUM RESEARCH. LITERARY GENRES+ OREGONCURRICULUM STUDY CENTER. EUGENE, PROJECT ENGLISH. THE BASIC CONVENTIONS THAT SHAPE THECREATION OF THE SHORT STORY AND THE NOVEL ARE EXAMINEDIN THIS 11TH-GRADE LITERATURE UN:T. THE SECTION ON THE SHORTSTORY ILLJSTRATES NARRATIVE FICTION FORM THROUGH THE SHORTSTORIES OF FORSTER. JACKSON, STEINBECK, THURBER. FOE,MCCULLERS. HAWTHORNE. MANSFIELD. SALINfER. STEELE. AND COLLIER.EMPHASIZED IN EACH STORY'S INTERPRETATION IS AN UNDERSTANDINGOF THE TRADITIONAL FORM REQUIREMENTS UNIQUE TO THE SHORTSTORY GENRE AND OF THE PARTICULAR LIMITATIONS IMPOSED UPON THEWRITER BY THIS FORM. THE SECTION ON THE NOVEL ILLUSTRATES THERANGE OF PROSE FICTION THROUGH THREE NOVELS CHOSEN FORANALYSIS- - "THE SCARLET LETTER,* THE GREAT GATSBY.6 AND THE MAYOR OF CAsTERBRIDGE.6 EACH NOVEL IS DISCUSSED ASA WHOLE. ANALYZED CHAPTER -BY- CHAPTER FOR CLOSER TEXTUALREADING. AND COMPARED WITH OTHER WORKS STUDIED. BOTH SECTIONSINCLUDE INDUCTIVE DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND WRITINGASSIGNMENTS DESIGNED TO CLARIFY THE STUDENT'S UNDERSTANDING OFSUBJECT. CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT, SETTING. SYMBOL. STYLE. TONE.FORM. AND POINT OF VIEW. TEXTS OF THE SHORT STORIES AND NOVELSARE NOT INCLUDED. FIVE TESTS DESIGNED TO ACCOMPANY THISUNIT ARE WENDED. -

Relay for Life Snhu Offers Bare Bones Education with Bare Bones Cost

"The man who smiles when things go wrong has thought of someone to blame it on." - Robert Bloch Volume XVI, Issue VI March 17th 2009 Manchester, NH SNHU Offers Bare Bones Education MARCH IS: RED Cross MONTH with Bare Bones Cost Aimee Terravechia Staff Writer Last fall, Southern New Advantage Program campuses Hampshire University began its and the Manchester campus revolutionary Advantage Pro- are all of the amenities, activi- gram at both the Salem and ties, and buildings that SNHU Nashua campuses. The pro- Manchester has. While on the gram allows students to begin on Manchester campus students a Bachelor's degree program or can work out at the gym, eat at Boston.com complete an Associate's degree the café, and live in the dorms. SNHU's Salem Center with costs only $10,000, accord- Nashua and Salem, however, ing to SNHU's website. The offer only the classrooms and What's Inside? program costs sixty-percent less tools necessary to pursue the Pages than SNHU's traditional Man- desired education. According to Relay for Life News 1-6 chester campus tuition, while an article in the Boston Globe, Clubs 7-13 offering the same classes, even business major Matthew Gam- taught by some of the same pro- A & E 14-18 bardella who attends the Salem fessors. location commented, saying, Ashley Manley Creative 19 While the core education "It's not the mainstream college News Editor Opinion 20 remains the same, there are experience, but it helps keep your Sports 21-27 noticeable differences between sights focused on your work." Voices & Faces 28 the estimated -

Female Portrayal in the Kpop Industry Title

Name: Luke Tang (27) Class: 3H1 Subject slant: Literature Topic: Female Portrayal in the Kpop Industry Title: “Of Unnies and Noonas” Unpacking TWICE as Portrayed in their Lyrical and Visual Media Chapter 1: Introductory Chapter a. General Background: In South Korea, gender inequality still continues to persist. The gender wage gap in South Korea remains over two times the average of 14.3%, with a clear link to gender inequality. There also continues to be gender gaps in representation in government, with the OECD even metaphorically describing the South Korean situation to be an uphill battle when it comes to fighting for the global goal of complete gender equality. (OECD, 2017) In the entertainment sector, sexual assault scandals shocking fans worldwide continue to unfold within the kpop industry, with the most recent of them allegedly involving circulation of sexually obscene videos of women. This was perpetrated by males in the kpop industry. Seungri, previously a member of Korean boy band BIGBANG, together with, Jung Joon-young, former Korean singer-songwriter. This sheds light on a growing issue of gender inequality with such cases being the most extreme of an inequality already present. TWICE, a South Korean girl group is the third most popular kpop group of 2019 according to Forbes and Ranker and they will be the focus of my paper. This is despite a notable contrast in concept that veers away from the kpop’s “girl crush”, a concept with sexy as well as occasionally tomboyish concepts. Being a visual and lyrical descriptor of kpop, the opposite lies in cute, aegyo concepts which TWICE primarily embodies and is known for. -

Longitudinal Codebook

Codebook European Election Study Longitudinal Data Set, version 15.10.2010 European Election Study Longitudinal Media Study 1999, 2004, 2009 University of Exeter and Universiteit van Amsterdam MEDIA CONTENT ANALYSIS DOCUMENTATION INITIAL RELEASE version 15.10.2010 1 GENERAL INFORMATION The purpose of the longitudinal data set is to: · Build a unified data set based on the content analysis of the news in the campaign for the 1999, 2004, and 2009 European elections in all the member states of the EU. · Ensure that the data can be linked to the other data collected in the European Election Study across all three elections. Sample: The content analysis was carried out on a sample of national news media coverage in 15 EU member states in 1999, in 24 EU member states in 2004, and in all 27 EU member states in 2009. In all waves, we focus on national television and newspapers because these media are consistently listed as the most important sources of information about the EU for citizens in Europe (Eurobarometer 54–62). In all three waves, we included the main national evening news broadcasts of the most widely watched public and commercial television stations by country. We also include one or two ‘quality’ (i.e. broadsheet) and one tabloid newspaper from each country. For countries without relevant tabloid newspaper the most sensationalist-oriented other daily newspaper was included. In 1999, the data set includes only one national broadsheet newspaper and thus is missing a sensationalist-oriented newspaper. In some countries, the exact outlets coded vary to a certain extent from year to year. -

The Coherent Pattern of Leadership Reflected in the Unique Attributes Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Karakey, Gustavo Martin (2018) The coherent pattern of leadership reflected in the unique attributes of the shepherd / flock motif within the Miletus Speech (Acts 20:17–38), 1 Peter 5:1–11, and John 21:15–19. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / London School of Theology. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/26485/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. -

Multiple Copy Titles 2020 New Titles for 2020

Multiple Copy Titles 2020 Brown County Central Library - 448-5825 Updated Mar 2020 New titles for 2020 99 Percent Mine by Sally Thorne 339 p Crush (n.): a strong and often short-lived infatuation, particularly for someone beyond your reach… Darcy Barrett has undertaken a global survey of men. She’s travelled the world, and can categorically say that no one measures up to Tom Valeska, whose only flaw is that Darcy’s twin brother Jamie saw him first and claimed him forever as his best friend. Despite Darcy’s best efforts, Tom’s off limits and loyal to her brother, 99%. That’s the problem with finding her dream man at age eight and peaking in her photography career at age twenty—ever since, she’s had to learn to settle for good enough. When Darcy and Jamie inherit a tumble-down cottage from their grandmother, they’re left with strict instructions to bring it back to its former glory and sell the property. Darcy plans to be in an aisle seat halfway across the ocean as soon as the renovations start, but before she can cut and run, she finds a familiar face on her porch: house-flipper extraordinaire Tom’s arrived, he’s bearing power tools, and he’s single for the first time in almost a decade. Suddenly Darcy’s considering sticking around to make sure her twin doesn’t ruin the cottage’s inherent magic with his penchant for grey and chrome. She’s definitely not staying because of her new business partner’s tight t-shirts, or that perfect face that's inspiring her to pick up her camera again. -

A Reading of the Works by Fukazawa Shichiro By

Compelling Moments of Collaboration: A Reading of the Works by Fukazawa Shichiro by Chizu Kanada B. A., Tsuda College, Tokyo, 1988 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies Department of Asian Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia August 1990 © Chizu Kanada, 1990 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of /UiflH SfaAieS The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date Au^t 30, 1110 DE-6 (2/88) ii Abstract This thesis is a study of the narrative strategies in the fiction of Fukazawa Shichiro (1914-87) and the ways in which these strategies work to solicit involvement in a compelling reading experience. The role of the narrator in each of the stories I discuss proves to be critical in the establishment of this relationship. And while I examine the thematic implications further enhanced by this solicitation, I have chosen to focus on how each story through its narrator produces those thematic messages. My emphasis on each work's technical aspect is also a deliberate, compensatory move, a reaction against the tendency of Japanese critics who slight the process of reading as a determining factor in their evaluation of Fukazawa's works.