Download the Ultimate Separatist Cage?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gerard J. Yun

GERARD J. YUN 288 Lourdes St. Waterloo, Ontario, N2L 1P5 [email protected], Ph: 519-886-1127 www.gerardyunteaching.com EDUCATION Degrees and Diplomas Doctor of Musical Arts in Choral Literature and Performance, University of Colorado at Boulder, College of Music, 1999, with specialization in choral-orchestral literature and techniques Master of Arts in Choral Conducting, California State University, Sacramento, School of Music, 1991 Bachelor of Science in Commerce (Marketing), Santa Clara University, Leavey School of Business, 1984 Other Specialized Training Intensive Study in Orchestral Conducting, Peter the Great Music Festival and Symposium Rimsky-Korsakov Conservatoire, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1996 Intensive Study in Choral/Orchestral Performance, Oregon Bach Festival, 1990-91 Teachers and Mentors in Western Classical Music Choral Lynn Whitten, University of Colorado at Boulder, 1991-99 Weston Noble, Luther College, 1984-2015 Choral/Orchestral Helmuth Rilling, Oregon Bach Festival, 1990-91 Donald Kendrick, California State University at Sacramento, 1989-91 Symphony Misha Kukuskin, Rimsky-Korsakov Conservatoire, 1996 Alexander Polichek, Rimsky-Korsakov Conservatoire, 1996 Opera Robert Spillman, University of Colorado at Boulder, 1994-97 Richard Boldrey, University of Colorado at Boulder, 1992-95 Henry Mollicone, San Jose Civic Light Opera and Santa Clara University, 1984-85 Teachers and Mentors in Cultural Musics Japanese Michael Chikuzen Gould, Dokyoku, Cody, Wyoming, 1999- Shakuhachi Yodo Kurahashi II, Meian Honkyoku, Kyoto, -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

The Importance of Music in Different Religions

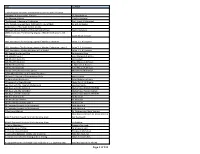

The Importance of Music in Different Religions By Ruth Parrott July 2009 Silverdale Community Primary School, Newcastle-under-Lyme. Key Words Spirituality Greetings Calls to Worship Blessings Dance in Hindu Worship Celebrations 2 Contents Introduction p4 The Teaching of RE in Staffordshire Primary Schools p6 Music and Spirituality p7 Assembly – ‘Coping with Fear’ p11 Suggestions for Listening and Response p14 Responses to Music and Spirituality p16 Worksheet – ‘Listening to Music’ KS2 p18 Worksheet – ‘Listening to Music’ KS1 p19 Judaism p20 Christianity p24 Islam p26 Sikhism p30 Hinduism p34 Welcomes, Greetings and Calls to Prayer/Worship p36 Lesson Plan – ‘Bell Ringing’ p38 Judaism – ‘The Shofar p42 Islam – ‘The Adhan’ p44 Lesson Plan – ‘The Islamic Call to Prayer’ p45 Celebrations p47 Lesson Plan – Hindu Dance ‘Prahlad and the Demon’ p50 Lesson Plan – Hindu Dance ‘Rama and Sita’ (Diwali) p53 Song: ‘At Harvest Time’ p55 Song: ‘Lights of Christmas’ p57 Blessings p61 Blessings from different religions p65 Lesson Plan – ‘Blessings’ p71 Conclusion p74 Song: ‘The Silverdale Miners’ p75 Song: ‘The Window Song’ p78 Acknowledgements, Bibliography p80 Websites p81 3 Introduction I teach a Y3 class at Silverdale Community Primary School, and am also the RE, Music and Art Co-ordinator. The school is situated in the ex- mining village of Silverdale in the borough of Newcastle- under-Lyme on the outskirts of Stoke-on-Trent and is recognised as a deprived area. The school is a one class entry school with a Nursery, wrap-around care and a breakfast and after school club. There are approximately 200 children in the school: 95% of pupils are white and 5% are a variety of mixed ethnic minorities. -

OCT 5 – NOV 25, 2018 Celebrate the Unifying Power of the World's Music

celebrate the unifying power of the world’s music OCT 5 – NOV 25, 2018 PRESENTED BY CCMUSICFEST.COM • Free Expanded Hot Breakfast • Business Center • Meeting Facilities • Whirlpool Suites • Group and Corporate Rates Available • Free High-Speed Internet Access • Indoor Heated Pool • On-Site Fitness Center • In-Room Refrigerator & Microwave 269.382.2303 1912 E. Kilgore Road, Kalamazoo (near the airport) www.countryinns.com/kalamazoomi TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome from the Executive Director . 3 Festival Dedication . 5 Note from the Board President . 6 MFSM Organization . 7 Festival Sponsors . 9 Festival Donors . 11 Preview of 2019 Events . 13 2018 EVENTS Timothy R . Botts, Expressive Calligraphy . 14 Bahar Ensemble & Orchestra Rouh . 15 PRESENTED BY Fifth House Ensemble, “Degenerate Art” . 16 Jordan Hamilton, Cello . 19 DIO Trio . 20 Festival Calendar . 22 Hindu Music & Dance . 25 HuDost . 27 Tlen-Huicani . 29 celebrate Sky Legends of the Three Fires . 31 the unifying Tapestry . 32 power of Arsentiy Kharitonov, Piano . 34 the world’s Sacred Waters Kirtan . 35 music Simon Shaheen . 36 Frances Kozlowski & Friends . 39 Organ with Brass & Voice . 41 Abraham Jam . 42 Messiah Sing . 44 Michigan Festival of Sacred Music We continue in our efforts to contribute to the sacred music P .O . Box 50566 repertoire by seeking to commission new works . The MFSM Kalamazoo, MI welcomes inquiries from donors interested in commissioning 49005-0566 works for future festivals . (269) 382-2910 Volunteers Welcome If you enjoy inspirational music, like to meet new people and www.mfsm.us receive free admission to concerts, please volunteer! Contact Find us on Facebook! us at (269) 382-29010 / director@mfsm .us and join us! WWW.MFSM.US • WWW.CCMUSICFEST.COM 1 ENJOYenjoy ENJOY MICHIGAN MICHIGANFESTIVAL FESTIVALSACRED ofSACREDMUSIC MUSIC presented by ev locit TM COMMUNICATION TRANSFORMED Exterior & Interior Digital Signs Integrating Communication For: Auditorium s • Church e s • Schools Theatr e s • Indus t r y • Ret a i l • Food evolocityAD.com 269.216.5950 5757 E. -

The 500 Most Influential Muslims = 2009 First Edition - 2009

the 500 most influential muslims = 2009 first edition - 2009 the 500 most influential muslims in the world = 2009 first edition (1l) - 2009 Chief Editors Prof John Esposito and Prof Ibrahim Kalin Edited and Prepared by Ed Marques, Usra Ghazi Designed by Salam Almoghraby Consultants Dr Hamza Abed al Karim Hammad, Siti Sarah Muwahidah With thanks to Omar Edaibat, Usma Farman, Dalal Hisham Jebril, Hamza Jilani, Szonja Ludvig, Adel Rayan, Mohammad Husni Naghawi and Mosaic Network, UK. all photos copyright of reuters except where stated All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the prior consent of the publisher. © the royal islamic strategic studies centre, 2009 �ملركز �مللكي للبحوث و�لدر��سات �لإ�سﻻمية )مبد�أ( the royal islamic strategic studies centre The Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service Georgetown University cmcu.georgetown.edu contents = introduction p.1 the diversity of islam p.4 top 50 p.17 the lists p.83 honorable mention p.84 lists contents p.86 1. Scholarly p.88 2. Political p.101 3. Administrative p.110 4. Lineage p.121 5. Preachers p.122 6. Women p.124 7. Youth p.131 8. Philanthropy p.133 9. Development p.135 contents 10. Science and Technology p.146 11. Arts and Culture p.148 Qur’an Reciters p.154 12. Media p.156 13. Radicals p.161 14. International Islamic Networks p.163 15. Issues of the Day p.165 glossary p.168 appendix p.172 Muslim Majority Map p.173 Muslim Population Statistics p.174 index p.182 note on format p.194 introduction The publication you have in your hands is the first of what we hope will be an annual series that provides a window into the movers and shakers of the Muslim world. -

Sounds Islamic? Muslim Music in Britain

Sounds Islamic? Muslim Music in Britain Carl Morris PhD Religious and Theological Studies Cardiff University 2013 For Rowan ‘May your heart always be joyful and may your song always be sung’ Bob Dylan – ‘Forever Young’ And to Lisa For sharing this journey, along with so many others Contents ________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements.....................................................................................................................iv List of Figures..............................................................................................................................vi List of Tables..............................................................................................................................viii Glossary.........................................................................................................................................ix Abstract..........................................................................................................................................x 1. Muslim Music in Britain: An Introduction.......................................................................1 • Contested Cultural Spaces: The Outline of a Research Agenda....................................................3 • Muslims and Musical Practice in Britain.......................................................................................9 • Traditions and Trajectories: An Examination of the Academic Literature..................................18 Section -

500 Most Influential Muslims of 2009

THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS = 2009 first edition - 2009 THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS IN THE WORLD = 2009 first edition (1M) - 2009 Chief Editors Prof John Esposito and Prof Ibrahim Kalin Edited and Prepared by Ed Marques, Usra Ghazi Designed by Salam Almoghraby Consultants Dr Hamza Abed al Karim Hammad, Siti Sarah Muwahidah With thanks to Omar Edaibat, Usma Farman, Dalal Hisham Jebril, Hamza Jilani, Szonja Ludvig, Adel Rayan, Mohammad Husni Naghawi and Mosaic Network, UK. all photos copyright of reuters except where stated All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the prior consent of the publisher. © the royal islamic strategic studies centre, 2009 أ �� ة � � ن ة � �ش� ة الم�م��لك�� ا �ل� ر د ��ة�� ا ل�ها �مة�� ة � � � أ ة � ة ة � � ن ة �� ا �ل� ���د ا �ل�د �ى د ا � � ال�مك� �� ا �ل� ل�ط� �� ر م أ ة ع ر ن و ة (2009/9/4068) ة � � ن � � � ة �ة ن ن ة � ن ن � � ّ ن � ن ن ة�����ح�م� ال�م�أ ��ل� كل� �م� ال�م��س�أ � ���� ا ��لها �ل� ���� �ع ن م�حة� � �م�ط��ه�� � �ل� ���ه�� �ه�� ا ال�م�ط��� �ل و أ �ل و وة وة � أ أوى و ة نأر ن � أ ة ���ة ة � � ن ة � ة � ة ن � . �ع� ر ا �ةى د ا �ر � الم ك��ن �� ا �ل�و ل�ط�ة�� ا �و ا �ةى ن��ه�� �ح �ل�و�مة�� ا �ر�ى ISBN 978-9957-428-37-2 املركز امللكي للبحوث والدراسات اﻹسﻻمية )مبدأ( the royal islamic strategic studies centre The Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding Edmund A. -

Dawud Wharnsby in a Whisper of Peace

AudioWith CD ISCOVER and celebrate the beauty Dof Islam with Dawud Wharnsby in A Whisper of Peace. D awud Each poem in this classic collection is full of faithful ideas and wide-eyed wonder. W Helping children to join the chorus of harnsby dawud Wharnsby birds tweeting, waves crashing, squirrels squeaking and voices singing, which praise the Creator. A Whisper First released in 1996 A Whisper of Peace has taken on a life of its own, continuing to inspire new generations and find its o way into the homes, schools and hearts of f PEACE listeners around the world. A WHISPER OF PEACE OF A WHISPER Recommended for ages 5+ Remastered audio CD in the book is percussion based. Royalties from sales of A Whisper of Peace go to a trust fund supporting educational initiatives for children, directly overseen by the author. ISBN 978-0-86037-534-0 | US $22.95 THE ISLAMIC FOUNDATION United Kingdom www.islamic-foundation.com DEDICATION dawud Wharnsby To the memory of my mother, Mary Janet Wharnsby (1938–2012), who guided my dreams, stitched my cape and encouraged me to fly. A Whisper of PEACE Illustrated by Shireen Adams THE ISLAMIC FOUNDATION DEDICATION dawud Wharnsby To the memory of my mother, Mary Janet Wharnsby (1938–2012), who guided my dreams, stitched my cape and encouraged me to fly. A Whisper of PEACE Illustrated by Shireen Adams THE ISLAMIC FOUNDATION A Whisper CONTENTS of PEACE First Published in 2014 by Bismillah 4 THE ISLAMIC FOUNDATION Distributed by ad Qamatis Salah 6 KUBE PUBLISHING LTD Q Tel +44 (01530) 249230, Fax +44 (01530) 249656 E-mail: [email protected] Takbir (Days of Eid) 10 Website: www.kubepublishing.com The songs on the accompanying digital CD were originally recorded with analogue l Khaliq 12 equipment. -

SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES SOME of OUR PAST SPONSORS Greetings

ISLAMIC SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA 54 Years of Service 55TH ISNA ANNUAL CONVENTION AUGUST 31 – SEPTEMBER 3, 2018 • HOUSTON, TEXAS SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES SOME OF OUR PAST SPONSORS Greetings, The Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) has completed 54 years of service to the American Muslim community. As an Umbrella organization, ISNA is widely regarded as the most significant convener of Muslims in North America. ISNA fosters the development of the Muslim Community through Annual Convention, Regional Conferences, Education Forums, Interfaith activities, Youth programs and other avenues. ISNA’s 55th Annual Convention will be held in Houston from August 31- September 3, 2018. This Convention is one of the largest gatherings of Muslims in North America. This year, our 54th Annual Convention in Chicago drew tens of thousands of attendees. In addition to the program, one of the main public attractions is the bazaar/trade show, which features over 500 booths, 400 vendors, and the work of dozens of non-profit organizations from around the country. There are 3 to 4 million Muslims in the United States and they rank in the top three US religious groups in per capita prosperity and education levels, car- rying roughly $124 billion in disposal income. The tens of thousands of ISNA convention attendees have a buying power of several hundred million dollars in disposal income. Among the attendees will be the trendsetters and key influencers of the community. Despite its obvious value as a consumer group, the American Muslim community has been largely overlooked by companies, creating a major opportunity for those that do engage them. -

The 500 Most Influential Muslims S 2010

THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS S 2010 THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS = 2010 first edition - 2010 CHIEF EDITORS Dr Joseph Lumbard and Dr Aref Ali Nayed PREPARED BY Usra Ghazi DESIGNED AND TYPESET BY Simon Hart CONSULTANT Siti Sarah Muwahidah WITH THANKS TO Aftab Ahmed, Emma Horton, Mark B D Jenkins, Lamya Al-Khraisha, Mohammad Husni Naghawi, Kinan Al-Shaghouri, Farah El-Sharif, Jacob Washofsky and Zahna Zurar All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the prior consent of the publisher. Copyright © 2010 by The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre ! l'd ð ! 1 ; ! ð "#D!ĵIJ( +,- "#D!1. øù "#Ï=ĆĄęAĴ ! 1 ð ð ! ! ð ! ð ; ! "#kF¡ J6ñ "#kFMij O Q RS( <=ôñ Z*+ øù a`^_ ! 1 (ȉȇȇȐ/Ȑ/ȋȇȍȏ ) ! ] ! 1 e ; 1 1 ( !rs 1 ! 1 1 !ð ! ð ð ÍË 1 ð ð q?) Z,Ŕ L=1,ghi! øù Ja "#,kj F¡mĘ RSJFpq µ´ "#D!1.J64 +,2jñ "#D!1ñJa JE{z| =ĆĄęĘ ÌÎ 2jñJij =ĆĄęA! ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 ʎ ɵ ɵ 3 ɴ (" #ɴ&) %ɵ& )*+1ʎ- " +"0 #1 " & '61ɴ 7ɵ 691 " ::91 " the royal islamic strategic studies centre CONTENTS = introduction 1 the diversity of islam 7 top 50 25 runners-up 91 the lists 95 1. Scholarly 97 2. Political 107 3. Administrative 115 4. Lineage 125 5. Preachers 127 6. Women’s Issues 131 7. Youth 137 8. Philanthropy 139 9. Development 141 10. Science, Technology, Medicine, Law 151 11. Arts and Culture 155 Qur’an Reciters 161 12. -

A Whisper of Peace by Dawud Wharnsby #F0XCLNDT2U6 #Free

A Whisper of Peace Dawud Wharnsby Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically A Whisper of Peace Dawud Wharnsby A Whisper of Peace Dawud Wharnsby Praise for Dawud Wharnsby's Colours of Islam: "[A] collection of modern poems and songs for Muslim children everywhere . combines religious thoughts with contemporary concerns and incorporates universal principles of truth, peace and faith."—Kirkus Reviews "Colours of Islam is yet another educational read by Wharnsby that is sure to educate all young readers on the principles of Islam. Recommended."—Canadian Review of Materials "Children and adults will be inspired and absorbed for hours."—Islamic Horizons From the well-known singer and Muslim convert Dawud Wharnsby, this delightful collection covers important themes in Islam—its message of peace, love of the Prophet Muhammad, God's nearness, and caring for and marvelling at the wonders of the world. Full of uplifting rhymes and faithful ideas, this collection will inspire and inform children of all faiths and none. Dawud Wharnsby was born in Canada in 1972. He has been writing stories, songs, and poems for people of all ages for many years. When he is not traveling to sing with audiences around the world, he loves being with his family—hiking in the mountains near his home, growing vegetables, and fixing things that get broken around the house. Dawud loves adventures and being outdoors so much that he is an official Ambassador for Scouting (UK), encouraging young people to take care of the earth and build strong communities. The Wharnsby family lives seasonally between their homes in Pakistan, Canada, and the United States. -

List of Books in Library

Title AUTHOR a simple guide to islams contribution to science and civilisation Daughter of the prophet (Zainab) SR. Nafees Khan The Missing Martyrs Charles Kurzman The Sunnah: A Source of Civilization Prof. Yusuf Al-Qaradawi YOU CAN BE THE HAPPIEST WOMAN IN THE WORLD Dr.AID AL QARNI 1) Honeybees That Build Perfect Combs 100 Inspirational Sayings of Prophet Muhammed Nazim Mangera 10001 Inventions The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilizations 3rd Edition Salim T.S. Al-Hassani 1001 Inventions The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization Salim T. S. Al-Hassani 1001 Inventions The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization - copy 2 Salim T. S. Al-Hassani 1001 Inventions: Muslim Heritage In Our World Salim T. S. Al-Hassani 101 Seerah Stories and Dua Saniyasnain Khan 110 Ahadith Qudsi 1 Syed Masood-Ul-Hasan 110 Ahadith Qudsi 1B Darussalam 110 Ahadith Qudsi 1C Syed Masood-ul-Hasan 110 Hadith Qudsi 1A S. Masood-ul-Hassan 110 Hadith Qudsi 1D Syed Masood-ul-Hasan 12 Dua' Immortalized in the Quran Muhammad Alshareef 2) The World Of Our Little Friends The Ants" 20 Piece Collection of Documentary DVDs Harun Yahya 30 Signs of the Hypocrites Aa'id Abdullah al Qarni 33 Lessons For Every Muslim Abdul Aziz S. Al Shomar 365 Days with the Prophet Muhammad Nurdan Damla 365 Days with the Sahaba 2 Mohammad KHALID PERWEZ 365 Days with the SAHABAH Mohammad Hashim Kamali 365 Days with the Sahabah Mohammad KHALID PERWEZ 365 Dua with Stories Ali KaraCam 365 Hadith with Stories Ali KaraCam 365 Hadith with Stories copy 2 Ali KaraCam 50 Concepts Brought By Muhammad Jalal Abualrub 50 Concepts Brought By Muhammad Jalal Abualrub A Boy from Makkah Dr.