Securing Community Acceptance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu Against the Cercado Dam: an Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?*

The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu against the Cercado Dam: An Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?* Sergi Vidal Parra** University of Deusto, País Vasco https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda34.2019.03 How to cite this article: Vidal Parra, Sergi. 2019. “The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu against the Cercado Dam: An Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?” Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 34: 45-68. https://doi.org/10.7440/ antipoda34.2019.03 Reception date: January 29, 2018; Acceptance date: August 28, 2018; Modification date: September 28, 2018. Abstract: Objective/Context: In recent years, decreasing water availability, accessibility, and quality in the Upper and Middle Guajira has led to the death of thousands of Wayúu people. This has been caused by precipitation 45 deficit and droughts and hydro-colonization by mining and hydropower projects. This study assesses the effectiveness of the Wayúu’s legal mobili- zation to redress the widespread violation of their fundamental rights on the basis of the enforceability and justiciability of the human right to water. Methodology: The study assesses the effects of the Wayúu’s legal mobiliza- tion by following the methodological approach proposed by Siri Gloppen, * This paper is result of two field studies conducted in the framework of my doctoral studies: firstly, PARALELOS a six-month research stay at the Research and Development Institute in Water Supply, Environmental Sanitation and Water Resources Conservation of the Universidad del Valle, Cali (2016-2017); secondly, the participation in the summer courses on “Effects of Lawfare: Courts and Law as Battlegrounds for Social Change” at the Centre on Law and Social Transformation (Bergen 2017). -

Determinación De La Capacidad De Carga Turística En La Playa De Palomino, Municipio De Dibulla, Guajira

DETERMINACIÓN DE LA CAPACIDAD DE CARGA TURÍSTICA EN LA PLAYA DE PALOMINO, MUNICIPIO DE DIBULLA, GUAJIRA Autores Leonardo Hernández Cubillos María Fernanda Montaño Bernal TESIS DE GRADO PARA OPTAR POR EL TÍTULO DE INGENIERO AMBIENTAL DIRECTOR Claudia Lilian Londoño Castañeda Socióloga MSc en Economía Aplicada CO-DIRECTOR Duvan Javier Mesa Fernández Ingeniero Ambiental MSc en Ciencias Ambientales GLOSARIO C Capacidad de carga: Es el límite máximo al que puede extenderse la población de un ecosistema, 1. E Equipamiento urbano: conjunto de edificios y espacios, predominantemente de uso público, en donde se realizan actividades complementarias a las de habitación y trabajo, que proporcionan a la población servicios de bienestar social y de apoyo a las actividades económicas, sociales, culturales y recreativas, (SEDESOL, 1999). S Servicios Conexos: Todos los servicios conexos al turismo, tales como guías, restaurantes, servicios o planes turísticos. Nota de aceptación: ___________________________ Firma del director ____________________________ Firma del Jurado Bogotá D.C. Diciembre del 2018 TABLA DE CONTENIDO RESUMEN .......................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................... 7 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ......................................................................................... 8 2. OBJETIVOS .............................................................................................. -

Diferendo Limites Cesar - Guajira

DIFERENDO LIMITES CESAR - GUAJIRA MAURICIO ENRIQUE RAMÍREZ ÁLVAREZ ANTENDECENTES Mediante oficio de fecha octubre 14 de 2012 el director del IGAC le informo a la Cámara de Representantes sobre el estado de los limites entre el Cesar y La Guajira EN ESTE OFICIO EL IGAC EXPLICA LO SIGUIENTE ORDENANZA 004 DE 1888 ASAMBLEA MAGDALENA DISTRITO SAN JUAN DEL CESAR se compone de las secciones de la Esperanza, Corral de Piedra, Caracolí, Guayacanal, El Rosario y la Sierrita DISTRITO DE VALLEDUPAR se compone por las secciones de Valencia de Jesús, San Sebastián de Rabago, Atanquez, Patilla, Badillo, Jagua de Pedregal y Venados ORDENANZA 038 DE 1912 LIMITES ENTRE SAN JUAN DEL CESAR Y VALLEDUPAR Serán los señalados en la Ley 279 de 1874 del extinguido Estado del magdalena así: a partir del punto en que por el lado del sudeste limita actualmente Valledupar con Villanueva, línea recta pasando por Sabanalarga, hasta llegar al manantial del Cerro el Higuerón, de donde sigue también en línea recta, hasta Tembladera en el camino de la Junta a la Despensa. De tembladera hasta tocar en el punto más cercano los límites del territorio Nacional de la Nevada. Esta Ordenanza fue reformada por la Ordenanza 063 de 1912, 006 de 1914 y finalmente derogada por la Ordenanza 055 de 1924. La Ordenanza 040 del 26 de abril de 1915 determina los limites mediante una descripción igual a la Ordenanza 038 de 1912, pero fue derogada por la Ordenanza 030 de 1916. La Ley 19 de 1964, por la cual se crea el Departamento de La Guajira, enumera los municipios que lo integran pero no señala los límites. -

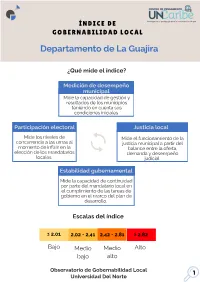

Gobernabilidad Local En La Guajira

ÍNDICE DE GOBERNABILIDAD LOCAL Departamento de La Guajira ¿Qué mide el índice? Medición de desempeño municipal Mide la capacidad de gestión y resultados de los municipios teniendo en cuenta sus condiciones iniciales Participación electoral Justicia local Mide los niveles de Mide el funcionamiento de la concurrencia a las urnas al justicia municipal a partir del momento de influir en la balance entre la oferta, elección de los mandatarios demanda y desempeño locales judicial Estabilidad gubernamental Mide la capacidad de continuidad por parte del mandatario local en el cumplimiento de las tareas de gobierno en el marco del plan de desarrollo. Escalas del índice ≤ 2,01 2,02 - 2,41 2,42 - 2,81 ≥ 2,82 Bajo Medio Medio Alto bajo alto Observatorio de Gobernabilidad Local 1 Universidad Del Norte Departamento de La Guajira Población: 985.452 de habitantes Extensión territorial: 20.848 Km2 División político-administrativa: 15 municipios La Guajira posee unas dinámicas territoriales caracterizadas por altos niveles de ruralidad y dispersión demográfica Índice de Gobernabilidad Local BAJO MEDIO BAJO MEDIO ALTO ALTO Barrancas, Dibulla, Maicao, Distracción, Manaure, Albania, El Molino Fonseca, La Jagua del Riohacha, y Hatonuevo. Pilar, San Juan del Uribia y Urumita. Cesar y Villanueva Observatorio de Gobernabilidad Local 2 Universidad Del Norte Resultados por municipio El municipio con el Índice de Gobernabilidad Local más bajo son Dibulla, Riohacha, Uribia y Urumita. Por el contrario, Albania, El Molino y Hatonuevo obtuvieron los resultados más altos -

Luis Alfonso Perez Guerra Rector San Juan Del Cesar

INFORME DE GESTIÓN 2014 INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE FORMACION TECNICA PROFESIOONAL INFOTEP RESULTADOS GESTIÓN 2014 INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE FORMACION TECNICA PROFESIOONAL INFOTEP RESULTADOS DE LA GESTIÓN POR PROCESOS PROCESOS MISIONALES GESTION ACADÉMICA OFERTA ACADÉMICA ACTUAL ESTUDIANTES MATRICULADOS PERIODOS 2010-2014 OFERTA ACADÉMICA ACTUAL ESTUDIANTES MATRICULADOS MINERIA 2010-2014 OFERTA ACADÉMICA ACTUAL ESTUDIANTES MATRICULADOS PRODUCCIÓN AGROPECUARIA 2010-2014 OFERTA ACADÉMICA ACTUAL ESTUDIANTES MATRICULADOS CONTABILIDAD 2010-2014 OFERTA ACADÉMICA ACTUAL ESTUDIANTES MATRICULADOS SECRETARIADO EJECUTIVO 2010-2014 OFERTA ACADÉMICA ACTUAL ESTUDIANTES MATRICULADOS PEDAGOGÍA INFANTIL 2010-2014 ANALISIS DE LA INFORMACIÓN OFERTA ACADEMICA CICLO 2010 – 2014 AÑO 2010 AÑO 2011 AÑO 2012 AÑO 2013 AÑO 2014 MINERIA 809 772 1069 1041 924 PRODUCION AGROPECUARIA 193 117 83 57 20 CONTABILIDAD 155 114 110 173 212 SECRETARIADO EJECUTIVO 135 148 152 131 86 PEDAGOGIA INFANTIL 238 217 163 99 199 TOTALES 1530 1368 1577 1501 1441 El comportamiento de los programas con relación al numero de estudiantes para el ciclo 2010 – 2014 se ve afectado a partir del año 2011 para el programa de producción agropecuaria en particular, esto esta relacionado con los periodos en los cuales este programa no fue ofertado debido a la baja o nula demanda estudiantil; de igual forma le siguen en su orden ascendente pedagogía infantil, secretariado ejecutivo, contabilidad y minería lo cual ha mostrado una excelente distribución a lo largo del ciclo. ARTICULACIÓN DE LA EDUCACIÓN TÉCNICA -

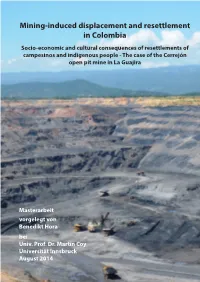

Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement in Colombia

Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people - The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Masterarbeit vorgelegt von Benedikt Hora bei Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Universität Innsbruck August 2014 Masterarbeit Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people – The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Verfasser Benedikt Hora B.Sc. Angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Science (M.Sc.) eingereicht bei Herrn Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Institut für Geographie Fakultät für Geo- und Atmosphärenwissenschaften an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebene Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich an den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurde, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. _______________________________ Innsbruck, August 2014 Unterschrift Contents CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Preface -

Departamento De La Guajira

DEPARTAMENTO DE LA GUAJIRA ADMINISTRACIÓN TEMPORAL DEL SECTOR DE AGUA POTABLE Y SANEAMIENTO BÁSICO PLAN DEPARTAMENTAL DE AGUA ANEXO No. 03 - ESPECIFICACIONES TÉCNICAS CONCURSO DE MÉRITOS CMA-AT-APSB-004-2020 OBJETO: “ELABORACIÓN DE ESTUDIOS Y DISEÑOS PARA LA REHABILITACIÓN Y/O OPTIMIZACIÓN DE LOS SISTEMAS DE TRATAMIENTO DE AGUAS RESIDUALES DE: BARRANCAS, SAN JUAN DEL CESAR, VILLANUEVA, URUMITA Y LA JAGUA DEL PILAR, DEPARTAMENTO DE LA GUAJIRA.” Riohacha, La Guajira, junio 2020 1 Calle 7 No. 9–25 Riohacha, La Guajira, Colombia Conmutador (571) 332 34 34 www.minvivienda.gov.co TABLA DE CONTENIDO ESPECIFICACIONES TÉCNICAS - DESCRIPCIÓN TÉCNICA DE LA CONSULTORÍA Y EQUIPO DE TRABAJO .................................................................................................. 5 1 INTRODUCCIÓN............................................................................................................. 5 2 OBJETIVOS Y ALCANCE .............................................................................................. 7 2.1 OBJETO GENERAL DE LA CONSULTORÍA ........................................................ 7 2.2 OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS Y ALCANCE DE LA CONSULTORÍA..................... 9 3 CONSIDERACIONES GENERALES ............................................................................. 9 3.1 ALCANCE GENERAL DE LOS TRABAJOS ......................................................... 9 3.2 ÁREA DEL PROYECTO ....................................................................................... 11 3.2.1 Localización proyecto .............................................................................. -

Diagnóstico De La Situación Del Pueblo Kogui

Diagnóstico de la situación del pueblo indígena Kogui UBICACIÓN GEOGRÁFICA DEL PUEBLO KOGUI. Procesado y georeferenciado por el Observatorio del Programa Presidencial de DH y DIH Vicepresidencia de la República Fuente base cartográfica: Igac Ubicación geográfica Los indígenas de la etnia Kogui ( o Kaggaba) habitan la vertiente norte y sur de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, en la parte correspondiente a Guatapuri, en lo que se conoce como Mauramake del Resguardo Arhuaco de la Sierra y la mayoría de la población Kogui vive en los departamentos de La Guajira, Cesar y Magdalena. Su población se estima en 9.911 personas y su lengua tradicional el Kawagian, pertenece a la familia lingüística Chibcha1. Tienen especial presencia en las partes altas de los municipios de Santa Marta, Ciénaga, Aracataca y Fundación en el departamento de Magdalena, Pueblo Bello y Valledupar en Cesar y Riohacha, Dibulla y San Juan del Cesar en La Guajira. Cómo se observa en el mapa, estos municipios comparten sus límites en la región de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Esta consideración no desconoce la presencia de estos indígenas en otras jurisdicciones. Como se verá más adelante los límites reconocidos por los pueblos indígenas están determinados por 1 Departamento Nacional de Planeación, Arango Ochoa Raúl, Enrique Sánchez Gutiérrez. Los Pueblos indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del nuevo milenio. Población, cultura y territorio: bases para el fortalecimiento social y económico de los pueblos indígenas. Página 356. Bogotá, 2004. OBSERVATORIO DEL PROGRAMA PRESIDENCIAL DE DERECHOS 1 HUMANOS Y DIH su creencia en la Ley original o Ley de la Madre y en la existencia de una Línea Negra que limita la región de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. -

La Guajira: Situación Sanitaria Covid-19 Necesidades Principales De La

FLASH UPDATE COVID 19 #1 – LA GUAJIRA Respuesta ELC 15 de mayo de 2020 LA GUAJIRA: SITUACIÓN SANITARIA COVID-19 Al día 14 de mayo en el departamento de La Guajira se reportan 32 casos de COVID-19, distribuidos así; 9 en Riohacha, 10 en Maicao, 3 en Albania, 2 en Distracción, 2 en Fonseca y 6 en San Juan del César. Se registran 4 fallecidos, 1 paciente hospitalizado en Valledupar y 1 recuperado. Se registran 2 casos positivos que han sido notificados por otros departamentos a donde los pacientes fueron remitidos por requerir servicios de mayor complejidad tecnológica. El número de pruebas realizadas en el departamento es de 779. Decreto 076 de 16 de marzo de 2020: Se declara calamidad pública y emergencia sanitaria en todo el territorio del departamento de La Guajira, hasta el 15 de mayo de 2020, agravado por los efectos de la temporada de sequía. Decreto 090 de 18 de marzo de 2020: Se declara emergencia sanitaria y calamidad pública en el Distrito de Riohacha. Departamento de La Guajira Decreto 096 del 25 de abril de 2020: Se adoptan y aplican medidas de aislamiento preventivo obligatorio en el Departamento de La Guajira y se dictan otras disposiciones en el marco de la pandemia COVID19. Decreto 106 del 03 de mayo de 2020: Se decreta en el Distrito de Riohacha el toque de queda de lunes a viernes desde las 7:00 p.m. hasta las 5:00 a.m, los fines de semana rige de viernes a las 7:00 p.m. hasta las 5:00 a.m. -

Rv .PROJECT REPORT

UNITED STATES THE INTERIOR SURVEY : r v .PROJECT REPORT :v Colombia Investigations : J (IR) CO-lt - Charles M. Tschanz U. S. Geological Survey ; :> Andres Jimeno V. and Jaime Cruz B. Institute Naclonal de Investigaciones Geologico-Mineras ;S:, "Geological "Survey^ ";-.- " - . .-. ,.- -. is preliminary* and has not edited -6ir% reviewed for confor- ty witfi^ Geological Survey tandards or nomenclature Prepared on behalf of the Agency for International Development U. S. Department of State and the Government of Colombia 1970 THE MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE SIERRA NEVADA de SANTA MARIA, COLOMBIA (ZONE I) by Charles M. Tschanz U. S. Geological Survey and Andres Jimeno V. and Jaime Cruz B. Institute Nacional de Investigaciones Geologico-Mineras CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT....................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION................................................... 2 NONMETALLIC MINERAL RESOURCES.................................. 4 Limes tone................................................. 4 Limestone near Durania............................... 6 Geology......................................... 6 Reserves.............'........................... 6 Chemical composition............................ 15 Factors affecting txploitation.................. 18 Limestone near the Rancheria valley.................. 18 Geology......................................... 18 Reserves........................................ 19 Chemical composition................................. 21 < Factors affecting exploitation.................. 22 Other -

La Guajira Caracterización Departamental Y Municipal Informe Presentado a Cerrejón Minería Responsable Investigadora Astrid M

La Guajira Caracterización Departamental y municipal Informe presentado a Cerrejón Minería responsable Investigadora Astrid Martínez Ortiz Asistentes de Investigación Peterson Medina Juan David Pachón Bogotá, 18 de enero de 2019 Contenido Introducción ................................................................................................. 12 1. Caracterización Geográfica ..................................................................... 12 Estructura geológica del departamento ............................................................................ 14 Vulnerabilidad por Desabastecimiento Hídrico ............................................................ 19 2. Caracterización Demográfica .................................................................. 20 Primeros poblamientos, demografía y economía hasta 1985 ............................................ 20 Principales variables demográficas ................................................................................... 21 Índice de Ruralidad Municipal ......................................................................................... 24 Composición étnica ........................................................................................................... 26 Transición demográfica y estructura por edad ................................................................. 26 Bono demográfico ............................................................................................................. 27 3. Minería e Hidrocarburos ........................................................................ -

KOGUI) Los Guardianes De La Armonía Del Mundo

CARACTERIZACIONES DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS DE COLOMBIA Dirección de Poblaciones. KAGGABBA (KOGUI) Los guardianes de la armonía del mundo. El pueblo indígena Kággabba, o Kogui1, es uno de los cuatro pueblos indígenas asentados en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Este territorio, de 21.158km2, es compartido con los Wiwa, los Iku (Arhuaco) y los Kankuamo. En esta extensión se localiza el resguardo Kogui-Malayo-Arhuaco y el Parque Natural Nacional Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. En la literatura antropológica sobre el pueblo indígena se utilizan los términos de “Kogi/ Kogui/ Cogui”. Los indígenas utilizan la palabra Kággabba, que en lengua significa “gente” o “la verdadera gente”. (Uribe, 1998). El pueblo Kággabba está ubicado en las laderas templadas del norte, oriente y occidente de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Están concentrados principalmente en la región vertiente norte sobre el mar Caribe, la cual presenta mayor precipitación pluvial en los afluentes de los ríos don Diego, Palomino, y Ancho. La lengua nativa se denomina Kogui y perteneciente a la familia lingüística Chibcha. Este pueblo tiene una arraigada identidad cultural y su Ley de Origen2 rige su cotidianidad, su existencia, sus problemáticas comunitarias y así mismo, orienta sanciones espirituales y sociales. _______________________________ 1 También conocido como Kággaba, Kogi, Kogui, Cagaba, Cogui, Coghui. 2. La Ley de Origen es la ontología o principio de los indígenas de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Son los mandatos, códigos naturales de Origen y la máxima autoridad ancestral que gobierna los pueblos. (Ver Glosario del Atlas para la Jurisdicción Especial de los Pueblos). 1 CARACTERIZACIONES DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS DE COLOMBIA Dirección de Poblaciones.