144 Cal.App.4Th 47, 50 Cal.Rptr.3D 607 Court of Appeal, Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title ODATE GAME

Title ODATE GAME : character design and modelling for Japanese modesty culture based independent video game Sub Title Author 鄒、琰(Zou, Yan) 太田, 直久(Ota, Naohisa) Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2014 Jtitle Abstract Notes 修士学位論文. 2014年度メディアデザイン学 第395号 Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-0000201 4-0395 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master's Thesis Academic Year 2014 ODATE GAME: Character Design and Modelling for Japanese Modesty Culture Based Independent Video Game Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University Yan Zou A Master's Thesis submitted to Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of Media Design Yan Zou Thesis Committee: Professor Naohisa Ohta (Supervisor) Associate Professor Kazunori Sugiura (Co-Supervisor) Associate Professor Nanako Ishido (Co-Supervisor) Abstract of Master's Thesis of Academic Year 2014 ODATE GAME: Character Design and Modelling for Japanese Modesty Culture Based Independent Video Game Category: Design Summary Game character design is an important part of game design. Game characters cannot be designed only according to the designer's experience or the players' preferences. They should be strongly associated to the game system and also the story. A good game character design is not only the reason for players to purchase the game but it also can improve players' entire game experience. -

Yūrei” W Japońskich Survival Horrorach : Analiza Wybranych Przykładów

Dominika Staszenko Motyw „yūrei” w japońskich survival horrorach : analiza wybranych przykładów Replay. The Polish Journal of Game Studies 1, 29-38 2014 Dominika Staszenko Uniwersytet Łódzki Motyw yūrei w japońskich survival horrorach — analiza wybranych przykładów Wprowadzenie W japońskiej mitologii określenie yūrei odnosi się do duchów zmarłych, które z ja- kichkolwiek przyczyn powróciły na ziemię i szukają kontaktu z ludźmi [Kijewska, 2012]. Według tradycyjnych wierzeń najczęstszym powodem ich przybycia do świata doczesnego są silne związki uczuciowe z bliskimi oraz pragnienie wykonania nie- dokończonych zadań. Należy podkreślić, że chociaż zdarzają się opowieści o yūrei, w których powrót motywowany jest pozytywnymi odczuciami, takimi jak miłość czy troska, to znacznie większa część przekazów odnosi się do duchów kierujących się chęcią zemsty i zadośćuczynienia za wyrządzone krzywdy. Istoty, których jedynym celem pobytu na ziemi jest krwawy odwet, noszą nazwę onryō. Termin yūrei pierwot- nie odnosił się do wszystkich powracających duchów zmarłych, jednakże obecnie czę- ściej utożsamiany jest z postacią mściwej istoty, wymierzającej karę żyjącym. Z tego względu określenie yūrei i onryō stosuję wymiennie. Japończycy od wieków wierzą, że w świecie żywych mogą przebywać byty nadna- turalne. Takie przekonanie ma swoje źródło w systemach praktyk religijnych, takich jak buddyzm czy sintoizm. Wiara w wędrówkę dusz, opiekuńczą moc duchów zmar- łych przodków czy niemal nieograniczoną możliwość wpływania istot nadnatural- nych na egzystencję żyjących sprawia, że japońska mitologia staje się inspiracją nawet dla współczesnych tekstów kultury, ponieważ zawiera szereg uniwersalnych moty- wów, które doskonale łączą tradycję z nowoczesnością. 29 Czym jest survival horror? Wraz ze wzrostem popularności filmów grozy, opierających się na motywie pośmiert- nej zemsty, postać onryō zaczęła pojawiać się również w grach wideo z gatunku survi- val horror. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

The Dreamcast, Console of the Avant-Garde

Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Vol 6(9): 82-99 http://loading.gamestudies.ca The Dreamcast, Console of the Avant-Garde Nick Montfort Mia Consalvo Massachusetts Institute of Technology Concordia University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We argue that the Dreamcast hosted a remarkable amount of videogame development that went beyond the odd and unusual and is interesting when considered as avant-garde. After characterizing the avant-garde, we investigate reasons that Sega's position within the industry and their policies may have facilitated development that expressed itself in this way and was received by gamers using terms that are associated with avant-garde work. We describe five Dreamcast games (Jet Grind Radio, Space Channel 5, Rez, Seaman, and SGGG) and explain how the advances made by these industrially productions are related to the 20th century avant- garde's lesser advances in the arts. We conclude by considering the contributions to gaming that were made on the Dreamcast and the areas of inquiry that remain to be explored by console videogame developers today. Author Keywords Aesthetics; art; avant-garde; commerce; console games; Dreamcast; game studios; platforms; politics; Sega; Tetsuya Mizuguchi Introduction A platform can facilitate new types of videogame development and can expand the concept of videogaming. The Dreamcast, however brief its commercial life, was a platform that allowed for such work to happen and that accomplished this. It is not just that there were a large number of weird or unusual games developed during the short commercial life of this platform. We argue, rather, that avant-garde videogame development happened on the Dreamcast, even though this development occurred in industrial rather than "indie" or art contexts. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

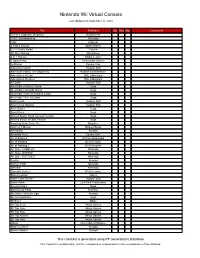

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Music Games Rock: Rhythm Gaming's Greatest Hits of All Time

“Cementing gaming’s role in music’s evolution, Steinberg has done pop culture a laudable service.” – Nick Catucci, Rolling Stone RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME By SCOTT STEINBERG Author of Get Rich Playing Games Feat. Martin Mathers and Nadia Oxford Foreword By ALEX RIGOPULOS Co-Creator, Guitar Hero and Rock Band Praise for Music Games Rock “Hits all the right notes—and some you don’t expect. A great account of the music game story so far!” – Mike Snider, Entertainment Reporter, USA Today “An exhaustive compendia. Chocked full of fascinating detail...” – Alex Pham, Technology Reporter, Los Angeles Times “It’ll make you want to celebrate by trashing a gaming unit the way Pete Townshend destroys a guitar.” –Jason Pettigrew, Editor-in-Chief, ALTERNATIVE PRESS “I’ve never seen such a well-collected reference... it serves an important role in letting readers consider all sides of the music and rhythm game debate.” –Masaya Matsuura, Creator, PaRappa the Rapper “A must read for the game-obsessed...” –Jermaine Hall, Editor-in-Chief, VIBE MUSIC GAMES ROCK RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME SCOTT STEINBERG DEDICATION MUSIC GAMES ROCK: RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME All Rights Reserved © 2011 by Scott Steinberg “Behind the Music: The Making of Sex ‘N Drugs ‘N Rock ‘N Roll” © 2009 Jon Hare No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. -

PDF ATF Dec12

> 2 < PRENSARIO INTERNATIONAL Commentary THE NEW DIMENSIONS OF ASIA We are really pleased about this ATF issue of world with the dynamics they have for Asian local Prensario, as this is the first time we include so projects. More collaboration deals, co-productions many (and so interesting) local reports and main and win-win business relationships are needed, with broadcaster interviews to show the new stages that companies from the West… buying and selling. With content business is taking in Asia. Our feedback in this, plus the strength and the capabilities of the the region is going upper and upper, and we are region, the future will be brilliant for sure. pleased about that, too. Please read (if you can) our central report. There THE BASICS you have new and different twists of business devel- For those reading Prensario International opments in Asia, within the region and below the for the first time… we are a print publication with interaction with the world. We stress that Asia is more than 20 years in the media industry, covering Prensario today one of the best regions of the world to proceed the whole international market. We’ve been focused International with content business today, considering the size of on Asian matters for at least 15 years, and we’ve been ©2012 EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL PAYMENTS TO THE ORDER OF the market and the vanguard media ventures we see attending ATF in Singapore for the last 5 years. EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL in its main territories; the problems of the U.S. and As well, we’ve strongly developed our online OR BY CREDIT CARD. -

Sega Dreamcast European PAL Checklist

Console Passion Retro Games The Sega Dreamcast European PAL Checklist www.consolepassion.co.uk □ 102 Dalmatians □ Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 □ Slave Zero □ 18 Wheeler American Pro Tucker □ Jet Set Radio □ Sno Cross: Championship Racing □ 4 Wheel Thunder □ Jimmy White 2: Cueball □ Snow Surfers □ 90 Minutes □ Jo Jo Bizarre Adventure □ Soldier of Fortune □ Aero Wings □ Kao the Kangaroo □ Sonic Adventure □ Aero Wings 2: Air Strike □ Kiss Psycho Circus □ Sonic Adventure 2 □ Alone in the Dark: TNN □ Le Mans 24 Hours □ Sonic Shuffle □ Aqua GT □ Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver □ Soul Calibur □ Army Men: Sarge’s Heroes □ Looney Tunes: Space Race □ Soul Fighter □ Bangai-O □ Magforce Racing □ South Park Rally □ Blue Stinger □ Maken X □ South Park: Chef’s Luv Shack □ Buggy Heat □ Marvel vs Capcom □ Space Channel 5 □ Bust A Move 4 □ Marvel vs Capcom 2 □ Spawn: In the Demon Hand □ Buzz Lightyear of Star Command □ MDK 2 □ Spec Ops 2: Omega Squad □ Caesars Palace 2000 □ Metropolis Street Racer □ Speed Devils □ Cannon Spike □ Midway’s Greatest Hits Volume 1 □ Speed Devils Online □ Capcom vs SNK □ Millennium Soldier: Expendable □ Spiderman □ Carrier □ MoHo □ Spirit of Speed 1937 □ Championship Surfer □ Monaco GP Racing Simulation 2 □ Star Wars: Demolition □ Charge ‘N’ Blast □ Monaco GP Racing Simulation 2 Online □ Star Wars: Episode 1 Racer □ Chicken Run □ Mortal Kombat Gold □ Star Wars: Jedi Power Battles □ Chu Chu Rocket! □ Mr Driller □ Starlancer □ Coaster Works □ MTV Sports Skateboarding □ Street Fighter 3: 3rd Strike □ Confidential Mission □ NBA 2K -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,686,269 B2 Schmidt Et Al

USOO8686269B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,686,269 B2 Schmidt et al. (45) Date of Patent: * Apr. 1, 2014 (54) PROVIDING REALISTIC INTERACTION TO (56) References Cited A PLAYER OF A MUSIC-BASED VIDEO GAME U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS (75) Inventors: Daniel A. Schmidt, Somery ille, MA 3.430,530D211,666 AS 3/19697/1968 GrindingerMacGillavry (US); Gregory B. LoPiccolo, Brookline, 3,897,711 A 8/1975 Elledge MA (US); Eran Egozy, Brookline, MA D245,038 S 7, 1977 Ebata et al. (US) D247,795 S 4, 1978 Darrell 4,128,037 A 12, 1978 Montemurro (73) Assignee: Harmonix Music Systems, Inc., E. 88: Sushida et al. Cambridge, MA (US) D262,017 S 11/1981 Frakes, Jr. D265,821 S 8, 1982 Okada et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this D266,664 S 10, 1982 Hoshino et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 (Continued) U.S.C. 154(b) by 823 days. This patent is Subject to a terminal dis- FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS claimer. AT 468071 T 6, 2010 AU T41239 B2 4f1999 (21) Appl. No.: 12/263,434 (Continued) (22) Filed: Oct. 31, 2008 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (65) Prior Publication Data Guitar Hero (video game) Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia— US 2009/OO82O78A1 Mar. 26, 2009 (Publisher RedOctane) Release Date Nov. 2005.* Related U.S. Application Data (Continued) (63) Continuation of application No. 1 1/683,136, filed on Mar. 7, 2007, now Pat. No. 7,459,624. Primary Examiner — Marlon Fletcher (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Wilmer Cutler Pickering (60) Provisional application No. -

Evolution of Game Controllers: Toward the Support of Gamers with Physical Disabilities

Evolution of Game Controllers: Toward the Support of Gamers with Physical Disabilities Dario Maggiorini(&), Marco Granato, Laura Anna Ripamonti, Matteo Marras, and Davide Gadia University of Milan, 20135 Milan, Italy {dariomaggiorini,marcogranato,lauraripamonti, davidegadia}@unimi.it, [email protected] Abstract. Video games, as an entertaining media, dates back to the ‘50s and their hardware device underwent a long evolution starting from hand-made devices such as the “cathode-ray tube amusement device” up to the modern mass-produced consoles. This evolution has, of course, been accompanied by increasingly spe- cialized interaction mechanisms. As of today, interaction with games is usually performed through industry-standard devices. These devices can be either general purpose (e.g., mouse and keyboard) or specific for gaming (e.g., a gamepad). Unfortunately, for marketing reasons, gaming interaction devices are not usually designed taking into consideration the requirements of gamers with physical disabilities. In this paper, we will offer a review of the evolution of gaming control devices with a specific attention to their use by players with physical disabilities in the upper limbs. After discussing the functionalities introduced by controllers designed for disabled players we will also propose an innovative game controller device. The proposed game controller is built around a touch screen interface which can be configured based on the user needs and will be accessible by gamers which are missing fingers or are lacking control in hands movement. Keywords: Video game Á Gaming devices Á Input device Á Game controller Á Physical disability 1 Introduction Video games, as an entertaining media, appeared around 1950. -

Sony Playstation

Sony PlayStation Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 007 Racing Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 101 Dalmatians II, Disney's: Patch's London Adventure Eidos Interactive 102 Dalmatians, Disney's: Puppies to the Rescue Eidos Interactive 1Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2Xtreme SCEA 2Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 3 Game Value Pack Volume #1 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #2 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #3 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #4 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #5 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #6 Agetec (Distributed by Tommo) 3D Baseball Crystal Dynamics 3D Lemmings: Long Box Ridged Psygnosis 3Xtreme 989 Studios 3Xtreme: Demo 989 Studios 40 Winks GT Interactive A-Train: Long Box Cardboard Maxis A-Train: SimCity Card Booster Pack Maxis Ace Combat 2 Namco Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere Namco Aces of the Air Agetec Action Bass Take-Two Interactive Action Man: Operation Extreme Hasbro Interactive Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600 Activision Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600: Greatest Hits Activision Adidas Power Soccer Psygnosis Adidas Power Soccer '98 Psygnosis Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron & Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft Acclaim Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron and Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft: Demo Acclaim Adventures of Lomax, The Psygnosis Agile Warrior F-111X: Jewel Case Virgin Agile Warrior F-111X: Long Box Ridged Virgin Games Air Combat: Long Box Clear Namco Air Combat: Greatest Hits Namco Air Combat: Jewel Case Namco Air Hockey Mud Duck Akuji the Heartless Eidos Aladdin in Nasira's Revenge, Disney's Sony Computer Entertainment..